The Garifuna Journey Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

“I'm Not a Bloody Pop Star!”

Andy Palacio (in white) and the Garifuna Collective onstage in Dangriga, Belize, last November, and with admirers (below) the voice of thPHOTOGRAPHYe p BYe ZACH oSTOVALLple BY DAVE HERNDON Andy Palacio was more than a world-music star. “I’m not a bloody pop star!” He was a cultural hero who insisted Andy Palacio after an outdoor gig in Hopkins, Belize, that revived the hopes of a was so incendiary, a sudden rainstorm only added sizzle. But if it Caribbean people whose was true that Palacio wasn’t a pop star, you couldn’t tell it from the heritage was slipping away. royal treatment he got everywhere he went last November upon 80 CARIBBEANTRAVELMAG.COM APRIL 2008 81 THE EVENTS OF THAT NOVEMBER TOUR WILL HAVE TO GO DOWN AS PALACIO’S LAST LAP, AND FOR ALL WHO WITNESSED ANY PART OF IT, THE STUFF OF HIS LEGEND. Palacio with his role model, the singer and spirit healer Paul Nabor, at Nabor’s home in Punta Gorda (left). The women of Barranco celebrated with their favorite son on the day he was named a UNESCO Artist for Peace (below left and right). for me as an artist, and for the Belizean people which had not been seen before in those parts. There was no as an audience.” The Minister of Tourism Belizean roots music scene or industry besides what they them- thanked Palacio for putting Belize on the map selves had generated over more than a dozen years of collabora- in Europe, UNESCO named him an Artist tion. To make Watina, they started with traditional themes and for Peace, and the Garifuna celebrated him motifs and added songcraft, contemporary production values as their world champion. -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines INTRODUCTION located on Saint Vincent, Bequia, Canouan, Mustique, and Union Island. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, like most of state in the Eastern Caribbean. The islands have a the English-speaking Caribbean, has a British combined land area of 389 km2. Saint Vincent, with colonial past. The country gained independence in an area of 344 km2, is the largest island (1). The 1979, but continues to operate under a Westminster- Grenadines include 7 inhabited islands and 23 style parliamentary democracy. It is politically stable uninhabited cays and islets. All the islands are and elections are held every five years, the most accessible by sea transport. Airport facilities are recent in December 2010. Christianity is the Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Country Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N COUNTRY VOLUME dominant religion, and the official language is fairly constant at 2.1–2.2 per woman. The crude English (1). death rate also remained constant at between 70 and In 2001 the population of Saint Vincent and 80 per 10,000 population (4). Saint Vincent and the the Grenadines was 102,631. In 2006, the estimated Grenadines has experienced fluctuations in its population was 100,271 and in 2009, it was 101,016, population over the past 20 years as a result of a decrease of 1,615 (1.6%) with respect to 2001. The emigration. According to the CIA World Factbook, sex distribution of the population in 2009 was almost the net migration rate in 2008 was estimated at 7.56 even, with males accounting for 50.5% (50,983) and migrants per 1,000 population (5). -

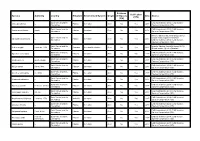

GRIIS Records of Verified Introduced and Invasive Species

Evidence Verification Species Authority Country Kingdom Environment/System Origin of Impacts Date Source (Y/N) (Y/N) Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Abrus precatorius L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Acacia auriculiformis Benth. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Saint Vincent and the Global Invasive Species Database. Adenanthera pavonina L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 Animalia terrestrial/freshwater Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Global Invasive Species Database. Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Ageratum conyzoides L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia procera Benth. (Roxb.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Allamanda cathartica L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Alpinia purpurata K.Schum. (Vieill.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). -

A Cruiser's View of Bequia

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS NOVEMBER 20088 NO.NO. 158 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore A CRUISER'S VIEW OF BEQUIA See story on page 28 WILFRED DEDERER NOVEMBER 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 a NOVEMBER 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 CALENDAR NOVEMBER 1 All Saints’ Day. Public holiday in French West Indies 1 Independence Day. Public holiday in Antigua & Barbuda 1 D Hamilton Jackson Day. Public holiday in USVI 1 - 2 Women’s Caribbean One Design Keelboat Championship, St. Maarten. [email protected] The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore 2 19th West Marine Caribbean 1500 sets sail from Hampton, VA to Tortola. www.carib1500.com www.caribbeancompass.com 3 Independence Day. Public holiday in Dominica 4 Community Service Day. Public holiday in Dominica NOVEMBER 2008 • NUMBER 158 6 - 11 Le Triangle Emeraude rally, Guadeloupe to Dominica. [email protected] 7 - 8 BVI Schools Regatta, Royal British Virgin Islands Yacht Club (RBVIYC), tel (284) 494-3286, [email protected], www.rbviyc.net 7 – 9 Heineken Regatta Curaçao. www.heinekenregattacuracao.com 7 – 9 BMW Invitational J/24 Regatta, St. Lucia. [email protected] Repo Man 8 Reclaiming a stolen yacht ..... 32 St. Maarten Optimist Open Championship. [email protected] 8 - 10 Triskell Cup Regatta, Guadeloupe. http://triskellcup.com TERI JONES 10 - 15 Golden Rock Regatta, St Maarten to Saba. CONNELLY-LYNN [email protected] 11 Veterans’ Day. Public holiday in Puerto Rico and USVI 11 Armistice Day. Public holiday in French West Indies and BVI 13 FULL MOON 13 - 21 Heineken Aruba Catamaran Regatta. -

The Afro-Nicaraguans (Creoles) a Historico-Anthropological Approach to Their National Identity

MARIÁN BELTRÁN NÚÑEZ ] The Afro-Nicaraguans (Creoles) A Historico-Anthropological Approach to their National Identity WOULD LIKE TO PRESENT a brief historico-anthropological ana- lysis of the sense of national identity1 of the Nicaraguan Creoles, I placing special emphasis on the Sandinista period. As is well known, the Afro-Nicaraguans form a Caribbean society which displays Afro-English characteristics, but is legally and spatially an integral part of the Nicaraguan nation. They are descendants of slaves who were brought to the area by the British between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries and speak an English-based creole. 1 I refer to William Bloom’s definition of ‘national identity’: “[National identity is] that condition in which a mass of people have made the same identification with national symbols – have internalized the symbols of the nation – so that they may act as one psychological group when there is a threat to, or the possibility of enhancement of this symbols of national identity. This is also to say that national identity does not exist simply because a group of people is externally identified as a nation or told that they are a nation. For national identity to exist, the people in mass must have gone through the actual psychological process of making that general identification with the nation”; Bloom, Personal Identity, National Identity and International Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990): 27. © A Pepper-Pot of Cultures: Aspects of Creolization in the Caribbean, ed. Gordon Collier & Ulrich Fleischmann (Matatu 27–28; Amsterdam & New York: Editions Rodopi, 2003). 190 MARIÁN BELTRÁN NÚÑEZ ] For several hundred years, the Creoles have lived in a state of permanent struggle. -

The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn University Scholar Projects University Scholar Program Spring 5-1-2021 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle A. Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects Part of the Immigration Law Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Shanelle A., "Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area" (2021). University Scholar Projects. 69. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects/69 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle Jones University Scholar Committee: Dr. Charles Venator (Chair), Dr. Virginia Hettinger, Dr. Sara Silverstein B.A. Political Science & Human Rights University of Connecticut May 2021 Abstract: The African Diaspora represents vastly complex migratory patterns. This project studies the journeys of English-speaking Afro-Caribbeans who immigrated to the US for economic reasons between the 1980s-present day. While some researchers emphasize the success of West Indian immigrants, others highlight the issue of downward assimilation many face upon arrival in the US. This paper explores the prospect of economic incorporation into American society for West Indian immigrants. I conducted and analyzed data from an online survey and 10 oral histories of West Indian economic migrants residing in the Greater Hartford Area to gain a broader perspective on the economic attainment of these immigrants. -

Canouan Estate Resort & Villas

MUSTIQUE THE ENT & GREN UNION ISLAND INC AD . V IN T ES CANOUAN S POINT JUPITER ESTATE RESORT & VILLAS ST. VINCENT MAYREAU CORBEC BAY HYAMBOOM BAY Canouan (pronounced ka-no-wan) is an island in the Grenadines, and one of nine inhabited and more than 20 uninhabited islands and cays which constitute Saint Vincent & The Grenadines. With a population of L’ANCE GUYAC BAY around 1,700, the small, at 3.5 miles (5.6km) by 1.25 miles (2km) yet inherently captivating island of Canouan BEQUIA BARBADOS R4 L’Ance Guyac is situated 25 miles (40km) South of Saint Vincent. Running along the Atlantic facing aspect of the island is 25 to 45 mins Beach Club PETIT MAHAULT BAY a barrier reef; whilst two bays separate its Southern side. The highest point on Canouan is Mount Royal. GRENADA 15 to 30 mins MUSTIQUE ST LUCIA 15 to 30 mins CANOUAN ST VINCENT SANDY LANE 10 mins YACHT CLUB LEGEND RESIDENCES TOBAGO CAYS K LITTLE BAY MAHAULT BEACH CANOUAN GOLF CLUB EVL TURTLE CREEK E31 IL SOGNO UNION ISLAND Canouan is accessible by POINT MOODY E27 BIG BLUE OCEAN E34 SILVER TURTLE air via five major gateways: CANOUAN ESTATE CHAPEL Barbados, St Lucia, Grenada, Martinique and ROAD mainland St Vincent. Its WHALING BAY airport features a 5900 ft runway, accommodating HIKING TRAIL private light, medium and some heavy jets for day or VILLAS RAMEAU BAY night landing. BOAT TRANSFERS Bellini’s Restaurant & Bar CARENAGE CANOTEN GV1 GV10 . La Piazza Restaurant & Bar E31 A4 CANOUAN ESTATE BOUNDARY R1 R2 A4 GV3 VILLAMIA GV14 THE BEACH HOUSE CATO BAY CS1 CS2 RUNWAY GV4 GOLF VILLA -

An Africana Womanist Reading of the Unity of Thought and Action

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 3, Ver. V (March. 2017) PP 58-64 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org An Africana womanist Reading of the Unity of Thought and Action Nahed Mohammed Ahmed Abstract:- This article examines the importance of establishing an authentic African-centered paradigm in Black Studies. In doing so, this article selects Clenora Hudson-Weems’ Africana womanism paradigm as an example. The unity of thought and action is the most important concept in this paradigm. The article tries to trace the main features of such a concept and how these features are different from these in other gender-based paradigms. Africana womanism, coming out of the rich and old legacy of African womanhood, then, is an authentic Afrocentric paradigm. Africana womanism is a term coined in the late 1980s by Clenora Hudson- Weems. As a pioneer of such an Africana womanist literary theory, Hudson-Weems explains the term Africana womanism as follows: Africana means African-Americans, African-Caribbeans, African-Europeans, and Continental Africans. Womanism is more specific because “terminology derived from the word ‘woman’ is . more specific when naming a group of the human race” (“Africana Womanism: An Overview” 205-17). Besides, womanism is a recall for Sojourner Truth's powerful speech, “And Ain't I a Woman " affirming that the Africana woman 's problem lies in being black and not in being a woman in which she was forced to speak about race issues because "she was hissed and jeered at because she was black, not because she was a woman, since she was among the community of women" (207).The present article uncovers the importance of Hudson-Weems’ quest for an authentic Africana paradigm through shedding light on her concept of the unity between thought and action, used by earlier authentic Africana paradigms, namely Black aestheticism and Afrocentricity In “Africana Womanism and the Critical Need for Africana Theory and Thought,” Hudson-Weems clarifies her concept of the unity between thought and action. -

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL Uma Análise Comparativa Entre Brasil E Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA

SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA REITOR João Carlos Salles Pires da Silva VICE-REITOR Paulo Cesar Miguez de Oliveira ASSESSOR DO REITOR Paulo Costa Lima EDITORA DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA DIRETORA Flávia Goulart Mota Garcia Rosa CONSELHO EDITORIAL Alberto Brum Novaes Angelo Szaniecki Perret Serpa Caiuby Alves da Costa Charbel Niño El Hani Cleise Furtado Mendes Evelina de Carvalho Sá Hoisel Maria do Carmo Soares de Freitas Maria Vidal de Negreiros Camargo O presente trabalho foi realizado com o apoio da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de pessoal de nível superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Código de financiamento 001 F. Humberto Cunha Filho Tullio Scovazzi organizadores SALVAGUARDA DO PATRIMÔNIO CULTURAL IMATERIAL uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália também com textos de Anita Mattes, Benedetta Ubertazzi, Mário Pragmácio, Pier Luigi Petrillo, Rodrigo Vieira Costa Salvador EDUFBA 2020 Autores, 2020. Direitos para esta edição cedidos à Edufba. Feito o Depósito Legal. Grafia atualizada conforme o Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990, em vigor no Brasil desde 2009. capa e projeto gráfico Igor Almeida revisão Cristovão Mascarenhas normalização Bianca Rodrigues de Oliveira Sistema de Bibliotecas – SIBI/UFBA Salvaguarda do patrimônio cultural imaterial : uma análise comparativa entre Brasil e Itália / F. Humberto Cunha Filho, Tullio Scovazzi (organizadores). – Salvador : EDUFBA, 2020. 335 p. Capítulos em Português, Italiano e Inglês. ISBN: -

SAINT VINCENT and the GRENADINES Pilot Program For

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) PHASE ONE PROPOSAL 1 SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL Contents Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. 5 Summary of Phase 1 Grant Proposal ................................................................................... 7 1.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 10 1.1 National Overview .................................................................................................. 11 1.1.1. Country Context ......................................................................................................... 11 2.0. Vulnerability Context .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Precipitation ............................................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Temperature ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1.3 Sea Level Rise ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.4 Climate Extremes ....................................................................................................... -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time.