KOLODNEY-THESIS-2014.Pdf (721.3Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shabbat Parshat Vaera at Anshe Sholom B'nai Lsrael Congregation

Welcome to Shabbat Parshat Vaera ANNOUNCEMENTS at Anshe Sholom B’nai lsrael Congregation We regret to inform you of the passing of Charles Smoler, father of Adam Smoler. January 12 – 13, 2018 / 26 Tevet 5778 Shiva will take place at Adam & Libby's home (507 W. Roscoe St. #2) Sunday, January 14, 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM & 5:15 - 8:30 PM, and Monday, January 15, 5:15 - 8:00 PM. May the memory of the righteous be a blessing and a comfort to us Kiddush is co-sponsored by Milt’s BBQ. all. Amen. ASBI Board of Directors: The next ASBI Board of Directors meeting is Monday, January 15, at 7:00 PM. Thank you to this week’s volunteer Tot Shabbat leader, Mayer Grashin, and SCHEDULE FOR SHABBAT volunteer readers, Yinnon Finer & Josh Shanes. Friday, January 12 Light Candles 4:23 PM Mincha, Festive Kabbalat Shabbat & Ma’ariv 4:25 PM ANSHE SHOLOM TRIBUTES Saturday, January 13 Aliyah Hashkama Minyan 8:00 AM Neil Berkowitz Shacharit with sermon by Rabbi Wolkenfeld 9:00 AM Alan Hepker A User's Guide to Prophecy Youth Tefillah Groups (see inside for details) 10:30 AM In Memory of Charles “Chip” Smoler, a”h Daf Yomi & Parsha Discussion with Dr. Leonard Kranzler 12:30 PM Donald & Julia Aaronson Mincha followed by Shalosh Seudot 4:10 PM R. Yehuda Aaronson Havdalah 5:24 PM Alison & Eytan Fox Denise & Stuart Sprague Yahrzeit Repeat Evening Sh’ma: January 12, after 5:26 PM Ruth Binter in memory of her father, Gershon Zev Futerko, a”h, and her mother, Latest time to recite Morning Sh’ma: January 13, 9:38 AM Chaya Futerko, a”h Allen Hoffman in memory of Dr. -

The Baal Shem-Toy Ballads of Shimshon Meltzer

THE BAAL SHEM-TOY BALLADS OF SHIMSHON MELTZER by SHLOMO YANIV The literary ballad, as a form of narrative metric composition in which lyric, epic, and dramatic elements are conjoined and whose dominant mood is one of mystery and dread, drew its inspiration from European popular ballads rooted in oral tradition. Most literary ballads are written in a concentrated and highly charged heroic and tragic vein. But there are also those which are patterned on the model of Eastern European popular ballads, and these poems have on the whole a lyrical epic character, in which the horrific motifs ordinarily associated with the genre are mitigated. The European literary ballad made its way into modern Hebrew poetry during its early phase of development, which took place on European soil; and the type of balladic poem most favored among Hebrew poets was the heroico-tragic ballad, whose form was most fully realized in Hebrew in the work of Shaul Tchernichowsky. With the appearance in 1885 of Abba Constantin Shapiro's David melek yifrii.:>e/ f:tay veqayyii.m ("David King of Israel Lives"), the literary ballad modeled on the style of popular ballads was introduced into Hebrew poetry. This type of poem was subsequently taken up by David Frischmann, Jacob Kahan, and David Shimoni, although the form had only marginal significance in the work of these poets (Yaniv, 1986). 1 Among modern Hebrew poets it is Shimshon Meltzer who stands out for having dedicated himself to composing poems in the style of popular balladic verse. These he devoted primarily to Hasidic themes in which the figure and personality of Israel Baal Shem-Tov, the founder of Hasidism, play a prominent part. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

A Hebrew Maiden, Yet Acting Alien

Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page i Reading Jewish Women Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page ii blank Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iii Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Reading Jewish Society Jewish Women IRIS PARUSH Translated by Saadya Sternberg Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2004 by Brandeis University Press Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or me- chanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. Originally published in Hebrew as Nashim Korot: Yitronah Shel Shuliyut by Am Oved Publishers Ltd., Tel Aviv, 2001. This book was published with the generous support of the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, Inc., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry through the support of the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment of Brandeis University, and the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute through the support of the Donna Sudarsky Memorial Fund. -

Good News & Information Sites

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing on: A NEW HORIZON IN U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONS: FROM AN AMERICAN EMBASSY IN JERUSALEM TO POTENTIAL RECOGNITION OF ISRAELI SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE GOLAN HEIGHTS Before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security Tuesday July 17, 2018, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2154 Chairman Ron DeSantis (R-FL) Ranking Member Stephen Lynch (D-MA) Introduction & Summary Chairman DeSantis, Vice Chairman Russell, Ranking Member Lynch, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing to discuss the potential for American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, in furtherance of U.S. national security interests. Israeli sovereignty over the western two-thirds of the Golan Heights is a key bulwark against radical regimes and affiliates that threaten the security and stability of the United States, Israel, the entire Middle East region, and beyond. The Golan Heights consists of strategically-located high ground, that provides Israel with an irreplaceable ability to monitor and take counter-measures against growing threats at and near the Syrian-Israel border. These growing threats include the extremely dangerous hegemonic expansion of the Iranian-Syrian-North Korean axis; and the presence in Syria, close to the Israeli border, of: Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Quds forces; thousands of Iranian-armed Hezbollah fighters; Palestinian Islamic Jihad (another Iranian proxy); Syrian forces; and radical Sunni Islamist groups including the al Nusra Levantine Conquest Front (an incarnation of al Qaeda) and ISIS. The Iranian regime is attempting to build an 800-mile land bridge to the Mediterranean, running through Iraq and Syria. -

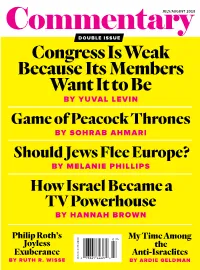

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Hartford Jewish Film Festival Film Festival

Mandell JCC | VIRTUAL Mandell JCC HARTFORD JEWISH HARTFORD JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL Mandell JCC | VIRTUAL Mandell JCC HARTFORD JEWISH HARTFORD JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28-APRIL 2, 2021 | WWW.HJFF.ORG Zachs Campus | 335 Bloomfield Ave. | West Hartford, CT 06117 | www.mandelljcc.org FILM SCHEDULE All films are available to view starting at 7:00pm. Viewing of films on the last day can begin up until 7:00pm. All Film Tickets - $12 per household DATE FILM PAGE TICKETS Feb 28-March 3 Holy Silence 11 Buy Now March 2-5 Asia 13 Buy Now March 3-6 Golden Voices 15 Buy Now March 5-8 Advocate 17 Buy Now March 6-9 When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit 19 Buy Now March 8-11 Here We Are 21 Buy Now March 9-12 ‘Til Kingdom Come 23 Buy Now March 11-14 Sublet 25 Buy Now March 13-16 My Name is Sara 27 Buy Now March 15-18 City of Joel 29 Buy Now March 16-19 Shared Legacies 30 Buy Now March 18-21 Incitement 33 Buy Now March 20-23 Thou Shalt Not Hate 35 Buy Now March 21-24 Viral 37 Buy Now March 23-26 Those Who Remained 39 Buy Now March 25-28 Latter Day Jew 41 Buy Now March 25-26 & 28-30 Mossad 43 Buy Now March 29-April 1 Shiva Baby 45 Buy Now March 30-April 2 The Crossing 47 Buy Now Mandell JCC Ticket Assistance: 860-231-6315 | [email protected] 2 | www.hjff.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 28 1 2 3 4 5 6 HOLY SILENCE GOLDEN VOICES ASIA WHEN.. -

Netanyahu Formally Denies Charges in Court

WWW.JPOST.COM THE Volume LXXXIX, Number 26922 JERUSALEFOUNDED IN 1932 M POSTNIS 13.00 (EILAT NIS 11.00) TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 27 SHVAT, 5781 Eye in the sky A joint goal Feminist religious art IAI unveils aerial Amos Yadlin on the need to When God, Jesus surveillance system 6 work with Biden to stop Iran and Allah were women Page 6 Page 9 Page 16 How did we miss Netanyahu formally denies charges in court Judges hint witnesses to be called only after election • PM leaves hearing early the exit • By YONAH JEREMY BOB two to three weeks to review these documents before wit- Prime Minister Benjamin nesses are called, that would ramp? Netanyahu’s defense team easily move the first witness fought with the prosecution beyond March 23. ANALYSIS on Monday at the Jerusalem Judge Rivkah Friedman Feld- • By YONAH JEREMY BOB District Court over calling man echoed the prosecution’s witnesses in his public cor- arguments that the defense A lifetime ago when living ruption trial before the March had between one to two years in northern New Jersey, I 23 election. to prepare for witnesses. But often drove further north for It seemed that the judges ultimately the judges did not work. were leaning toward calling seem anxious to call the first Sometimes the correct exit the first witness in late March witness before March 23. was small and easy to miss. or early April, which they A parallel fight between the But there were around five would present as a compro- sides was the prosecution’s or so exits I could use to avoid mise between the sides. -

1 Lahiton [email protected]

Lahiton [email protected] 1 Lahiton magazine was founded in 1969 by two partners, Uri Aloni and David Paz, and was funded by an investment from Avraham Alon, a Ramlah nightclub owner and promoter. Uri Aloni was a pop culture writer and rabid music fan while David Paz, another popular music enthusiast, was an editor who knew his way around the technical side of print production. The name “Lahiton,” reportedly invented by entertainers Rivka Michaeli and Ehud Manor, combines the Hebrew words for hit, “lahit” and newspaper, “iton.” Lahiton [email protected] 2 Uri Aloni cites the British fan magazines Melody Maker and New Music Express as influences; (Eshed 2008) while living in London and writing for the pop music columns of Yediot Ahronot and La-Isha, he would lift editorial content and photos from the latest British pop magazines, write articles, then find an Israel-bound traveler at the London airport to transport the articles into the hands of his editors. In Lahiton’s early days, Aloni and Paz continued this practice (Edut 2014). Eventually, however Lahiton’s flavor became uniquely secular Israeli. Although in 1965 the Beatles were famously denied permission to perform in Israel (Singer 2015), by the time Lahiton got started in 1969 there was no stemming the tide; the international pop music scene had permeated Israel’s insular and conservative culture. At the time there were no other Hebrew publications that covered what was going on both at home and in America and Europe. Lahiton began as a bimonthly publication, but within the first year, when press runs of 5000 copies sold out on a regular basis, Paz and Aloni turned it into a weekly. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Ak Büyü / Sh'chur Geç Evlilik / Late Marriage Or (Hazinem) / Or (My Treasure)

Pera Film, toplumun sınırlarına karşı özgürlüğü için mücadele eden çarpıcı kadın karakterleri canlandırmış Ronit Elkabetz’e saygı duruşu niteliğinde bir seçki sunuyor. Ak Büyü / Sınırların Ötesi, Elkabetz’in aile, gelenekler, evlilik ve devletin kurumsal dayatmaları Sh’Chur karşısında özgürlükleri için mücadele eden ve bu nedenle toplumda sıradışı kabul edilen kadınlarla ilgili olarak yarattığı bir dizi unutulmaz karakter sayesinde, hem İsrail Yönetmen / Director: Shmuel Hasfari hem de Avrupa sinemasında bir dönüşüme imza attığı çalışmalarını izleyiciyle Oyuncular / Cast: Gila Almagor, Ronit Elkabetz, 7 – 28 Kasım | November 2018 Eti Adar, Hanna Azoulay Hasfari buluşturuyor. İsrail / Israel, 1994, 98’, renkli / color İbranice; Türkçe altyazılı / Sınırların Ötesi programı, Elkabetz’in kimi zaman oyuncu kimi zaman da yönetmen Hebrew with Turkish subtitles olarak yer aldığı, kariyerinde büyük bir öneme sahip dokuz filme yer veriyor. İsrail’de yaşayan Fas topluluğunun renkli ve tutku dolu kültürünü betimleyen Ak Büyü, aile ve Ak Büyü, İsrail’de yaşayan Fas topluluğunun renkli ve tutku dolu kültürüne evlilik kavramlarını genç bir adamın yaşadıkları üzerinden trajikomik bir anlatıyla odaklanıyor. Film, tamamen Batılılaşmış genç bir Sabra kızı olan 13 yaşındaki gösteren Geç Evlilik, hayatı üzerindeki tüm kontrolünü yitirmiş Ruthie’yle, ona başka Rachel’in aile üyelerinin düzenli olarak yaptıkları ak büyüyü (Sh’Chur) anlamaya ve bir iş bulmaya çalışan kızının hikayesini anlatan Or (Hazinem), hem eşi hem de onunla uzlaşmaya çalışmasını anlatıyor.