The Narrative Consistency of the Warcraft Movie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

Heroes of the Storm™ Open Beta Now Live!

The Nexus Beckons: Heroes of the Storm™ Open Beta Now Live! Heroes everywhere are invited to answer the call and tune into the launch celebration event for China on May 31 SHANGHAI, China, May 19, 2015 — It’s time to rally your fellow heroes and let the battles begin! Blizzard Entertainment Inc. and NetEase Inc. today jointly announced that the Nexus portal is wide open to heroes everywhere, as open beta testing for Heroes of the Storm™, its brand-new free-to-play online team brawler for Windows® PC, is now live in China. Heroes of the Storm brings together a diverse cast of iconic characters from Blizzard’s far-flung realms of science fiction and fantasy, including the Warcraft®, StarCraft® and Diablo® universes, to compete in epic, adrenaline-charged battles. Players can download the game and start playing immediately—head over to the official Heroes of the Storm website to get started. “We’re thrilled to finally open the Nexus to everyone,” said Mike Morhaime, CEO and cofounder of Blizzard Entertainment. “We’ve built Heroes of the Storm to be very fun and easy to pick up, with lots of variety and strategic depth through the different characters and battlegrounds. We can’t wait to see the action unfold as new players join in and take 20 years’ worth of Blizzard heroes and villains into battle.” “We're excited to see the all-star lineup from every one of Blizzard's franchises meet up in Heroes of the Storm," said William Ding, CEO and founder of NetEase. “Blizzard has had a huge influence on Chinese players and the local market over the past two decades. -

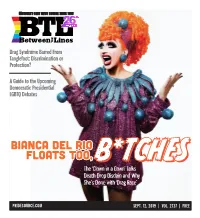

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Document 273 5-5-2014 – Download

Case 2:07-cv-00552-DB-EJF Document 273 Filed 05/05/14 Page 1 of 46 PROSE 1 SOPHIA STEWART P.O. BOX 31725 2 Las Vegasl NV 89173 3 702-501-5900 (PH) 4 ... IN PROPRIA PERSONA v: ---;;:\-CQ\( 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT \l~YU I I "' 6 FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH 7 SOPHIA STEWART, HON. EVELYN J. FURSE 8 Plaintiff, v. HON. DEE BENSON 9 MICHAEL STOLLER, GARY BROWN, Case No.: 2:07CV552 DB-EJF 10 DEAN WEBB, AND JONATHAN 11 LUBELL OBJECTION TO COURT DENIAL Defendants. TO AWARD DAMAGES AGAINST 12 DEFENDANT LUBELL AND 13 DEMAND FOR EXPEDITED AWARD 14 15 16 COMES NOW1 PLAINTIFF SOPHIA STEWART1 bringing forth the Objection To the 17 Court's Denial To Award Damages Against All Defendants And Demand For 18 Expedited Award of Damages in the amount of One Billion Three Hundred and 19 Sixty Seven Million $1,367,000,000.00 dollars for The Matrix Trilogy damages and 20 Three point five Billion $3,580,000,000.00 dollars in damages for the Terminator 21 Franchise Series. 22 23 Plaintiff brings forth this objection against the court for violating the 24 Plaintiff's constitutional Sixth and fourth amendments "Due Process and Equal 25 Protection" rights and obstructing her from a jury trial and the ability to face the 26 defendants in court for more than 6 years while Jonathan Lubell was deceased, 27 thus constituting a violation of racial discrimination and fraud. Racial 28 discrimination by concerted action is a federal offense under 18 U.S.C. -

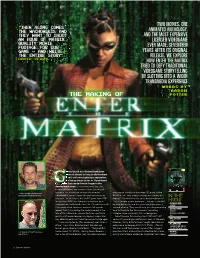

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Blizzard's Worlds Collide When Heroes of the Storm™ Launches June 2

Blizzard's Worlds Collide When Heroes of the Storm™ Launches June 2 Everyone's invited to join the battle for the Nexus when open beta testing begins on May 19 IRVINE, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Rally your fellow heroes and get ready for battle, because the portal to the Nexus is about to bust wide open! Blizzard Entertainment announced today that Heroes of the Storm™ will officially launch on June 2, following an open beta testing period beginning May 19. The free-to-play online team brawler brings together a diverse cast of iconic characters from Blizzard's far-flung realms of science fiction and fantasy, including the Warcraft®, StarCraft®, and Diablo® universes, and challenges them to compete in epic, adrenaline-charged battles. Heroes of the Storm invites players to customize heroes to suit their style and then team up with friends for some all-out mayhem. The game features a variety of gameplay modes for players of every skill level, including Cooperative, in which players team up against computer-controlled opponents, and Quick Match, an accessible way to jump in and play versus others. Experienced players can also join forces against other teams of players in highly competitive, draft-style ranked play. "With its focus on team play and fast-paced fun, Heroes of the Storm is a fresh take on a very popular genre," said Mike Morhaime, CEO and cofounder of Blizzard Entertainment. "We've built Heroes of the Storm in a way that makes it accessible to new players, but also challenging enough for veterans who really want to put their skills to the test. -

Blizzcon Is Bigger Than Ever with Nine Stages, 12 Trucks, 200+ Broadcast Streams

BlizzCon Is Bigger Than Ever With Nine Stages, 12 Trucks, 200+ Broadcast Streams The live stages feed into central Master Control, ‘Post Hub’ BY JASON DACHMAN, CHIEF EDITOR NOVEMBER 2, 2018 We distribute to a huge number amount of platforms and we also localize in 18 different languages. All of our esports programming is free, and we make the decision what goes on R Logotext Lorem TaglineBlizzCon Virtual Ticket holistically across Blizzard [based on] what we feel our community would want access to. Peter Eminger, Sr. Director Blizzard With 40,000 fans onsite watching five live esports stages and four content stages sprawled across a million square feet at Anaheim Convention Center, it simply doesn’t get any bigger for the Blizzard Entertainment pro- duction operation than BlizzCon. In addition, Blizzard’s Global Broadcast team is distributing a whopping 211 unique broadcast streams to 17 outlets in 18 languages. “For us, the live event and the broadcasts are very linked together because so much of the broadcast is from these live stages. Our show is definitely bigger this year,” says Pete Emminger, senior director, Blizzard Entertain- ment. “We’re really lucky in that we have a lot of consistent crew, so this year has actually been the smoothest year so far. Plus, we’ve really had a great year at Blizzard overall, so we’re extremely excited to finally be here at BlizzCon, which is really a celebration for us as much as it is [for the fans].” A Blizzard of Activity: A Dozen Mobile Units Onsite Serving Nine Stages Now in its 14th year, the convention features everything from live esports competitions to Q&A panels and announcements to demos of upcoming game releases to concerts and much more. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Transmedia Storytelling in the Warcraft Universe: the Role of Intermediality in Shaping the Warcraft Lore

Transmedia Storytelling in the Warcraft Universe: the Role of Intermediality in Shaping the Warcraft Lore Eszter Barabás A research Paper submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2020 Declaration I have read and I understand the plagiarism provisions in the General Regulations of the University Calendar for the current year, found at: http://www.tcd.ie/calendar I have also completed the Online Tutorial on avoiding plagiarism ‘Ready, Steady, Write’, located at http://tcd-ie.libguides.com/plagiarism/ready-steady-write I declare that the work described in this research Paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: Eszter Barabás 2020 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research Paper upon request. Signed: Eszter Barabás 2020 Summary This paper examines the popular franchise known as Warcraft, applying the theory of intermediality to the different mediums that contribute to it, analyzing each of their roles and how intermediality manifests across all platforms. The three established forms of intermediality, that of medial transposition, media combination and intermedial references are used, as well as the concept of transmedia storytelling, considered a fourth type. These categories are first introduced and defined, along with the vast network of media artifacts that contribute to the Warcraft lore. Each consecutive chapter focuses on one form of intermediality, applying it to a few representative works from the Warcraft franchise. -

Breaking the Code of the Matrix; Or, Hacking Hollywood

Matrix.mss-1 September 1, 2002 “Breaking the Code of The Matrix ; or, Hacking Hollywood to Liberate Film” William B. Warner© Amusing Ourselves to Death The human body is recumbent, eyes are shut, arms and legs are extended and limp, and this body is attached to an intricate technological apparatus. This image regularly recurs in the Wachowski brother’s 1999 film The Matrix : as when we see humanity arrayed in the numberless “pods” of the power plant; as when we see Neo’s muscles being rebuilt in the infirmary; when the crew members of the Nebuchadnezzar go into their chairs to receive the shunt that allows them to enter the Construct or the Matrix. At the film’s end, Neo’s success is marked by the moment when he awakens from his recumbent posture to kiss Trinity back. The recurrence of the image of the recumbent body gives it iconic force. But what does it mean? Within this film, the passivity of the recumbent body is a consequence of network architecture: in order to jack humans into the Matrix, the “neural interactive simulation” built by the machines to resemble the “world at the end of the 20 th century”, the dross of the human body is left elsewhere, suspended in the cells of the vast power plant constructed by the machines, or back on the rebel hovercraft, the Nebuchadnezzar. The crude cable line inserted into the brains of the human enables the machines to realize the dream of “total cinema”—a 3-D reality utterly absorbing to those receiving the Matrix data feed.[footnote re Barzin] The difference between these recumbent bodies and the film viewers who sit in darkened theaters to enjoy The Matrix is one of degree; these bodies may be a figure for viewers subject to the all absorbing 24/7 entertainment system being dreamed by the media moguls. -

Play Chapter: Video Games and Transmedia Storytelling 1

LONG / PLAY CHAPTER: VIDEO GAMES AND TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING 1 PLAY CHAPTER: VIDEO GAMES AND TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING Geoffrey Long April 25, 2009 Media in Transition 6 Cambridge, MA Revision 1.1 ABSTRACT Although multi‐media franchises have long been common in the entertainment industry, the past two years have seen a renaissance of transmedia storytelling as authors such as Joss Whedon and J.J. Abrams have learned the advantages of linking storylines across television, feature films, video games and comic books. Recent video game chapters of transmedia franchises have included Star Wars: The Force Unleashed, Lost: Via Domus and, of course, Enter the Matrix ‐ but compared to comic books and webisodes, video games still remain a largely underutilized component in this emerging art form. This paper will use case studies from the transmedia franchises of Star Wars, Lost, The Matrix, Hellboy, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and others to examine some of the reasons why this might be the case (including cost, market size, time to market, and the impacts of interactivity and duration) and provide some suggestions as to how game makers and storytellers alike might use new trends and technologies to close this gap. INTRODUCTION First of all, thank you for coming. My name is Geoffrey Long, and I am the Communications Director and a Researcher for the Singapore‐MIT GAMBIT Game Lab, where I've been continuing the research into transmedia storytelling that I began as a Master's student here under Henry Jenkins. If you're interested, the resulting Master's thesis, Transmedia Storytelling: Business Aesthetics and Production at the Jim Henson Company is available for downloading from http://www.geoffreylong.com/thesis. -

Mapping the Canadian Video and Computer Game Industry

Mapping the Canadian Video and Computer Game Industry Nick Dyer-Witheford [email protected] A talk for the “Digital Poetics and Politics” Summer Institute, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Aug 4, 2004 1 Introduction Invented in the 1970s as the whimsical creation of bored Pentagon researchers, video and computer games have over thirty years exploded into the fastest growing of advanced capitalism’s cultural industries. Global revenues soared to a record US$30 billion in 2002 (Snider, 2003), exceeding Hollywood’s box-office receipts. Lara Croft, Pokemon, Counterstrike, Halo and Everquest are icons of popular entertainment in the US, Europe, Japan, and, increasingly, around the planet. This paper—a preliminary report on a three-year SSHRC funded study—describes the Canadian digital play industry, some controversies that attend it and some opportunities for constructive policy intervention. First, however, a quick overview of how the industry works. How Play Works Video games are played on a dedicated “console,” like Sony’s PlayStation 2 or Microsoft’s Xbox, connected to a television, or on a portable “hand-held” device, like Nintendo’s Game Boy. Computer games are played on a personal computer (PC). There is also a burgeoning field of wireless and cell phone games. Irrespective of platform, digital game production has four core activities: development, publishing, distribution and licensing. Development--the design of game software-- is the industry’s wellspring. No longer the domain of lone-wolf developers, making a commercial game is today a lengthy, costly, and cooperative venture; lasts twelve months to three years, costs $2 to 6 million, and requires 20 to 100 people.