Mapping the Canadian Video and Computer Game Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867 12-28-1867 Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/banner1867 Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation "Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867" (1867). Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867. 34. https://digital.kenyon.edu/banner1867/34 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867 by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. /4ii- '\. /!L-__,_-fk.._ ~-'r,.J-~. -- J Kfi ·)./47 II.VA! Ii' ' ,<?'-'· h Ir. ~ J L ~ /4l.~~, --~:<"'7~ :- --- _.:: =----- ' -----~-s.~--l!P VOLUl\iE XXXI. MOUNT VERNON. OHIO: S~\TURDAY, DECEI\IBER 28. 1867. NUMBER 36. lrritten for tlte ..Jlt. Jre1 non Bam1er. In addition fo the aLove, tlie following re How the Heathen Rage. 'J.'ct·l'iMc Railro:ul Cal:uuit!' ! 'l'IIE 'l'A 'l''l'LERS. WI Sol't~ of f.l:~rngrQpn;;. Qtge ~cmocrntic ~mrner ceiverl slight injur,es: H. M. Ruesell, Frank· The disrnppointment ofeomc 01 the ltadicale --------~--~,--,_, ______ _ iS PtrBLtSllf,:D P.V..ERlr SA.TURDA.Y UORNlNO BY OCye ~rm.ocratic ~nnnc.r Jin, 'renn.j J. Brown, Buffalo; J. Owy~t', New Brown nn,! Trumbull, contestnots in th6 at the action of Congress on impeachment is RY T'iPPA. Sll!'\DON?-,"ET, FH'TY-FIVE PERSOXS KILLED! York; J. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Sweet Nothing: Real-World Evidence of Food and Drink Taxes and Their Effect on Obesity

SWEET NOTHING Real-World Evidence of Food and Drink Taxes and their Effect on Obesity NOVEMBER 2017 Tax PETER SHAWN TAYLOR - 1 - The Canadian Taxpayers Federation (CTF) is a federally ABOUT THE incorporated, not-for-profit citizen’s group dedicated to lower taxes, less waste and accountable government. The CTF was CANADIAN founded in Saskatchewan in 1990 when the Association of Saskatchewan Taxpayers and the Resolution One Association TAXPAYERS of Alberta joined forces to create a national organization. FEDERATION Today, the CTF has 130,000 supporters nation-wide. The CTF maintains a federal office in Ottawa and regional offic- es in British Columbia, Alberta, Prairie (SK and MB), Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic. Regional offices conduct research and advocacy activities specific to their provinces in addition to acting as regional organizers of Canada-wide initiatives. CTF offices field hundreds of media interviews each month, hold press conferences and issue regular news releases, commentaries, online postings and publications to advocate on behalf of CTF supporters. CTF representatives speak at functions, make presentations to government, meet with poli- ticians, and organize petition drives, events and campaigns to mobilize citizens to affect public policy change. Each week CTF offices send out Let’s Talk Taxes commentaries to more than 800 media outlets and personalities across Canada. Any Canadian taxpayer committed to the CTF’s mission is welcome to join at no cost and receive issue and Action Up- dates. Financial supporters can additionally receive the CTF’s flagship publication The Taxpayer magazine published four times a year. The CTF is independent of any institutional or partisan affilia- tions. -

Document 273 5-5-2014 – Download

Case 2:07-cv-00552-DB-EJF Document 273 Filed 05/05/14 Page 1 of 46 PROSE 1 SOPHIA STEWART P.O. BOX 31725 2 Las Vegasl NV 89173 3 702-501-5900 (PH) 4 ... IN PROPRIA PERSONA v: ---;;:\-CQ\( 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT \l~YU I I "' 6 FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH 7 SOPHIA STEWART, HON. EVELYN J. FURSE 8 Plaintiff, v. HON. DEE BENSON 9 MICHAEL STOLLER, GARY BROWN, Case No.: 2:07CV552 DB-EJF 10 DEAN WEBB, AND JONATHAN 11 LUBELL OBJECTION TO COURT DENIAL Defendants. TO AWARD DAMAGES AGAINST 12 DEFENDANT LUBELL AND 13 DEMAND FOR EXPEDITED AWARD 14 15 16 COMES NOW1 PLAINTIFF SOPHIA STEWART1 bringing forth the Objection To the 17 Court's Denial To Award Damages Against All Defendants And Demand For 18 Expedited Award of Damages in the amount of One Billion Three Hundred and 19 Sixty Seven Million $1,367,000,000.00 dollars for The Matrix Trilogy damages and 20 Three point five Billion $3,580,000,000.00 dollars in damages for the Terminator 21 Franchise Series. 22 23 Plaintiff brings forth this objection against the court for violating the 24 Plaintiff's constitutional Sixth and fourth amendments "Due Process and Equal 25 Protection" rights and obstructing her from a jury trial and the ability to face the 26 defendants in court for more than 6 years while Jonathan Lubell was deceased, 27 thus constituting a violation of racial discrimination and fraud. Racial 28 discrimination by concerted action is a federal offense under 18 U.S.C. -

Acquisition of Innova Q4 Investor Presentation – February 2021 Eg7 in Short

ACQUISITION OF INNOVA Q4 INVESTOR PRESENTATION – FEBRUARY 2021 EG7 IN SHORT 2,061 EG7 is a unique eco-system within the video games industry consisting of: SEKm REVENUE 1. An IP-portfolio consisting of world-class brands with both own IP’s such as P R O F O R M A 2 0 2 0 Everquest, PlanetSide, H1Z1 and My Singing Monsters, as well as licensed IP’s such as Lord of the Rings, DC Universe, Dungeons and Dragons and MechWarrior. o This Games-as-a-Service (“GaaS”) portfolio accounts for the majority of the revenues and profits with predictable monthly revenues. 2. Petrol, the number one gaming marketing agency. o That is why Activision, Embracer, Ubisoft among other repeat clients use 652 Petrol. SEKm ADJ. EBITDA 3. Sold Out, our publisher that has never had an unprofitable release. P R O F O R M A o That is why Frontier, Team17 and Rebellion among other repeat clients use 2 0 2 0 Sold Out. FY2020 PRO FORMA FINANCIALS (SEKm) CURRENT EG7 GROUP INNOVA TOTAL NEW GROUP 32% Revenue 1,721 340 2,061 ADJ. EBITDA MARGIN Adjusted EBITDA 512 140 652 Adjusted EBITDA margin 30% 41% 32% Number of employees 635 200 835 Net cash position 568 30 598 835 EMPLOYEES Total number of outstanding shares (million) 77 +10 87 EG7 PLATFORM VALUE CHAIN – WE CONTROL THE VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPING MARKETING PUBLISHING DISTRIBUTING WE TAKE THE COMPANIES WE ACQUIRE TO A NEW LEVEL PORTFOLIO OF WORLD-CLASS IP RELEASED 1999 RELEASED 2012 RELEASED 2015 RELEASED 2012 5 RELEASED 2007 RELEASED 2011 RELEASED 2006 RELEASED 2013 SELECTION OF GAME PIPELINE 10+ 40+ 5+ 10+ UNDISCLOSED MARKETING CAMPAIGNS REMASTERED / PROJECTS PROJECTS AND RELEASES NEW VERSIONS OF PORTFOLIO HISTORY & FINANCIALS +302% Revenue per Year SEK 2,061.0 (Pro-forma Revenue) Revenue Growth per Year +573% SEK 512.4m Contract worth Consulting in SEK 40m with (Pro-forma Revenue) Development Leyou +52% -3% +586% SEK 7.5m SEK 11.4m SEK 11.1m SEK 76.1m 2015-08 2016-08 2017-08 2018-121 2019-12 2020-12 1) Changed to calendar year. -

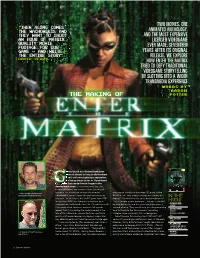

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

TYLER WILSON Lead Artist Tylerwilson.Art Vancouver, BC [email protected] +1-604-771-4577

TYLER WILSON Lead Artist tylerwilson.art Vancouver, BC [email protected] +1-604-771-4577 Summary ● 10 years of Leadership experience and 20 years in the game industry. ● Detail oriented, organized, and technical (rigs, problem solving, pipelines, best practices) ● Excellent written communication as well as documentation and tutorial experience. ● Always working towards the big picture studio goals. ● Loves: Games, Film, Anatomy Sculpts, Cloth Sims, Mentoring, Hockey. Skills Tools ● Character Creation ● Maya, XGen ● Digital Tailoring ● 3ds Max ● Technical Art ● ZBrush ● Scheduling & Organization ● Marvelous Designer ● Outsourcing ● Substance Painter, Mari ● Leadership ● Marmoset Toolbag, Keyshot, Arnold Experience Lead Artist Oct 2019 – Present Brass Token Games ● Provide overall artistic leadership and review all art assets for quality and continuity with the Creative Director’s vision. ● Light key assets through static and dynamic lighting. ● Help and manage art outsourcers to provide feedback, determine opportunities for efficiencies and cost savings, and help integrate art assets into the engine. ● Support the creation of marketing and pitch materials. Digital Tailor Mar 2019 – Present Freelance ● Continued creation of many items of clothing and complete outfits including accessories for Brud. Brud is a transmedia studio that creates digital character driven story worlds (Virtual Digital Influencers). ● Created two versions of a clean room tyvek Scientist outfit for System Shock 3, before and after Mutant infection. Lead Artist Mar 2016 – Mar 2019 Hothead Games ● Manage a team of twelve internal artists including 1on1's and mentoring. ● Set the art direction and worked closely with the team to reach our goals. ● Featured by Apple in "Gloriously Gorgeous Games" category. ● Brought high fidelity art to the mobile market. -

Sierra Club of Canada V. Canada (Minister of Finance) (2002), 287

Canwest Publishing lnc./Publications Canwest Inc., Re, 2010 ONSC 222, 2010 ... -----·---------------·------·----~-2010 ONSC 222, 2010 CarswellOnt 212, [2010] O.J. No. 188, 184 A.C.W.S. (3d) 684,~------·-------, ... Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister ofFinance) (2002), 287 N.R. 203, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club of Canada) 18 C.P.R. (4th) 1, 44 C.E.L.R. (N.S.) 161, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club ofCanada) 211 D.L.R. (4th) 193, 223 F.T.R. 137 (note), 20 C.P.C. (5th) 1, 40 Admin. L.R. (3d) 1, 2002 SCC 41, 2002 CarswellNat 822, 2002 CarswellNat 823, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club of Canada) 93 C.R.R. (2d) 219, [2002] 2 S.C.R. 522 (S.C.C.)- followed Statutes considered: Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36 Generally - referred to s. 4 - considered s. 5 - considered s. 11.2 [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.2(1) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.2(4) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4 [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4(1) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4(2) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.7(2) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - referred to s. 11.51 [en. 2005, c. 47, s. 128] - considered s. 11.52 [en. 2005, c. 47, s. 128] - considered Courts ofJustice Act, R.S.O. -

REGAIN CONTROL, in the SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME from REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT and 505 GAMES, COMING in 2019 World Premiere

REGAIN CONTROL, IN THE SUPERNATURAL ACTION-ADVENTURE GAME FROM REMEDY ENTERTAINMENT AND 505 GAMES, COMING IN 2019 World Premiere Trailer for Remedy’s “Most Ambitious Game Yet” Revealed at Sony E3 Conference Showcases Complex Sandbox-Style World CALABASAS, Calif. – June 11, 2018 – Internationally renowned developer Remedy Entertainment, Plc., along with its publishing partner 505 Games, have unveiled their highly anticipated game, previously known only by its codename, “P7.” From the creators of Max Payne and Alan Wake comes Control, a third-person action-adventure game combining Remedy’s trademark gunplay with supernatural abilities. Revealed for the first time at the official Sony PlayStation E3 media briefing in the worldwide exclusive debut of the first trailer, Control is set in a unique and ever-changing world that juxtaposes our familiar reality with the strange and unexplainable. Welcome to the Federal Bureau of Control: https://youtu.be/8ZrV2n9oHb4 After a secretive agency in New York is invaded by an otherworldly threat, players will take on the role of Jesse Faden, the new Director struggling to regain Control. This sandbox-style, gameplay- driven experience built on the proprietary Northlight engine challenges players to master a combination of supernatural abilities, modifiable loadouts and reactive environments while fighting through the deep and mysterious worlds Remedy is known and loved for. “Control represents a new exciting chapter for us, it redefines what a Remedy game is. It shows off our unique ability to build compelling worlds while providing a new player-driven way to experience them,” said Mikael Kasurinen, game director of Control. “A key focus for Remedy has been to provide more agency through gameplay and allow our audience to experience the story of the world at their own pace” “From our first meetings with Remedy we’ve been inspired by the vision and scope of Control, and we are proud to help them bring this game to life and get it into the hands of players,” said Neil Ralley, president of 505 Games. -

Relevant Stories from Library Databases

RELEVANT STORIES FROM ONLINE DATABASES Susanne Craig, Globe and Mail, 16 November 1999: The real reason Herald staff are hitting the bricks: At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity The real reason Herald staff are hitting the bricks At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity Tuesday, November 16, 1999 IN CALGARY -- When Dan Gaynor leaves work, he has to drive his white Jeep Cherokee past angry reporters. Rather than look at the striking employees, the publisher of The Calgary Herald tends to stare straight ahead. This is nothing new, many of the striking journalists say. They believe Mr. Gaynor's newspaper has been looking in only one direction for years. More than 200 newsroom and distribution workers at the Herald have been on strike since last Monday. They are trying to win their first union contract and, officially, they are at odds with their employer over such issues as wages and seniority rights. But ask the news hounds why they are on strike and the issues on the bargaining table never come up. Instead, they say they are angry because the Herald shapes the news, sometimes to favour a certain person or a certain point of view. -

Research Report

RESEARCH REPORT OCUFA Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations Union des Associations des Professeurs des Universités de l’Ontario 83 Yonge Street, Suite 300, Toronto, Ontario M5C 1S8 Telephone: 416-979-2117 •Fax: 416-593-5607 • E-mail: [email protected] • Web Page: http://www.ocufa.on.ca Ontario Universities, the Double Cohort, and the Maclean’s Rankings: The Legacy of the Harris/Eves Years, 1995-2003 Michael J. Doucet, Ph.D. March 2004 Vol. 5, No. 1 Ontario Universities, the Double Cohort, and the Maclean’s Rankings: The Legacy of the Harris/Eves Years, 1995-2003 Executive Summary The legacy of the Harris/Eves governments from 1995-2003 was to leave Ontario’s system of public universities tenth and last in Canada on many critical measures of quality, opportunity and accessibility. If comparisons are extended to American public universities, Ontario looks even worse. The impact of this legacy has been reflected in the Maclean’s magazine rankings of Canadian universities, which have shown Ontario universities, with a few notable exceptions, dropping in relation to their peers in the rest of the country. Elected in 1995 on a platform based on provincial income tax cuts of 30 per cent and a reduction in the role of government, the Progressive Conservative government of Premier Mike Harris set out quickly to alter the structure of both government and government services. Most government departments were ordered to produce smaller budgets, and the Ministry of Education and Training was no exception. Universities were among the hardest hit of Ontario’s transfer-payment agencies, with budgets cut by $329.1 million between 1995 and 1998, for a cumulative impact of $2.3 billion by 2003.