Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweet Nothing: Real-World Evidence of Food and Drink Taxes and Their Effect on Obesity

SWEET NOTHING Real-World Evidence of Food and Drink Taxes and their Effect on Obesity NOVEMBER 2017 Tax PETER SHAWN TAYLOR - 1 - The Canadian Taxpayers Federation (CTF) is a federally ABOUT THE incorporated, not-for-profit citizen’s group dedicated to lower taxes, less waste and accountable government. The CTF was CANADIAN founded in Saskatchewan in 1990 when the Association of Saskatchewan Taxpayers and the Resolution One Association TAXPAYERS of Alberta joined forces to create a national organization. FEDERATION Today, the CTF has 130,000 supporters nation-wide. The CTF maintains a federal office in Ottawa and regional offic- es in British Columbia, Alberta, Prairie (SK and MB), Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic. Regional offices conduct research and advocacy activities specific to their provinces in addition to acting as regional organizers of Canada-wide initiatives. CTF offices field hundreds of media interviews each month, hold press conferences and issue regular news releases, commentaries, online postings and publications to advocate on behalf of CTF supporters. CTF representatives speak at functions, make presentations to government, meet with poli- ticians, and organize petition drives, events and campaigns to mobilize citizens to affect public policy change. Each week CTF offices send out Let’s Talk Taxes commentaries to more than 800 media outlets and personalities across Canada. Any Canadian taxpayer committed to the CTF’s mission is welcome to join at no cost and receive issue and Action Up- dates. Financial supporters can additionally receive the CTF’s flagship publication The Taxpayer magazine published four times a year. The CTF is independent of any institutional or partisan affilia- tions. -

The Cord • Wednesday

. 1ng the 009 Polaris prize gala page19 Wednesday, September 23. 2009 thecord.ca The tie that binds Wilfrid Laurier University since 1926 Larger classes take hold at Laurier With classes now underway, the ef fects of the 2009-10 funding cuts can be seen in classrooms at Wil frid Laurier University, as several academic departments have been forced to reduce their numbers of part-time staff. As a result, class sizes have in creased and the number of class es offered each semester has decreased.' "My own view is that our admin istration is not seeing the academic side of things clearly;' said professor of sociology Garry Potter. "I don't think they properly have their eyes YUSUF KIDWAI PHOTOGRAPHY MANAGER on the ball as far as academic plan Michaellgnatieff waves to students, at a Liberal youth rally held at Wilt's on Saturday; students were bussed in from across Ontario. ninggoes:' With fewer professors teaching at Laurier, it is not possible to hold . as many different classes during the academic year and it is also more lgnatieff speaks at campus rally difficult to host multiple sections for each class. By combining sections and reduc your generation has no commit the official opposition, pinpointed ing how many courses are offered, UNDA GIVETASH ment to the political process;' said what he considers the failures of the the number of students in each class Ignatieff. current Conservative government, has increased to accommodate ev I am in it for the same The rally took place the day fol including the growing federal defi eryone enrolled at Laurier. -

I STATE of the ARTS: FACTORS INFLUENCING ONTARIO

STATE OF THE ARTS: FACTORS INFLUENCING ONTARIO ELEMENTARY TEACHERS’ PERFORMING ARTS INSTRUCTION By Paul R. Vernon A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Education in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Education Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December 2014 Copyright © Paul R. Vernon, 2014 i Abstract This thesis examines Ontario elementary teachers perceptions of their teaching of the performing arts (i.e., music, drama, and dance), through responses to an online survey. Participants (N = 138) described multiple aspects of their training and experiences in the performing arts, their comfort in teaching the performing arts, and the degree to which they thought they were teaching the expectations in the curriculum document. The document “The Arts, Grades 1-8, 2009” clearly describes (a) many benefits of performing arts practice, (b) elements of practice and instruction in each performing arts area, (c) how the creative process is a part of and enhanced by participation in these activities, and (d) guidelines for assessment of and through the arts, in addition to (e) describing the many mandated specific expectations for each subject and Grade level. However, few studies have addressed the training and experience of the teachers of the performing arts, and there is a pressing need for baseline data about performing arts instruction to inform hiring, certification, and professional development policies. Descriptive statistics are presented which detail many varied elements of performing arts instruction in Ontario schools, and ANOVAs are used to compare the differences between training groups on teachers perceptions of their comfort, the frequency and duration of their instruction, and their adherence to the curricular expectations. -

Harris Disorder’ and How Women Tried to Cure It

Advocating for Advocacy: The ‘Harris Disorder’ and how women tried to cure it The following article was originally commissioned by Action Ontarienne contre la violence faite aux femmes as a context piece in training material for transitional support workers. While it outlines the roots of the provincial transitional housing and support program for women who experience violence, the context largely details the struggle to sustain women’s anti-violence advocacy in Ontario under the Harris regime and the impacts of that government’s policy on advocacy work to end violence against women. By Eileen Morrow Political and Economic Context The roots of the Transitional Housing and Support Program began over 15 years ago. At that time, political and economic shifts played an important role in determining how governments approached social programs, including supports for women experiencing violence. Shifts at both the federal and provincial levels affected women’s services and women’s lives. In 1994, the federal government began to consider social policy shifts reflecting neoliberal economic thinking that had been embraced by capitalist powers around the world. Neoliberal economic theory supports smaller government (including cuts to public services), balanced budgets and government debt reduction, tax cuts, less government regulation, privatization of public services, individual responsibility and unfettered business markets. Forces created by neoliberal economics—including the current worldwide economic crisis—still determine how government operates in Canada. A world economic shift may not at first seem connected to a small program for women in Ontario, but it affected the way the Transitional Housing and Support Program began. Federal government shifts By 1995, the Liberal government in Ottawa was ready to act on the neoliberal shift with policy decisions. -

Sierra Club of Canada V. Canada (Minister of Finance) (2002), 287

Canwest Publishing lnc./Publications Canwest Inc., Re, 2010 ONSC 222, 2010 ... -----·---------------·------·----~-2010 ONSC 222, 2010 CarswellOnt 212, [2010] O.J. No. 188, 184 A.C.W.S. (3d) 684,~------·-------, ... Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister ofFinance) (2002), 287 N.R. 203, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club of Canada) 18 C.P.R. (4th) 1, 44 C.E.L.R. (N.S.) 161, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club ofCanada) 211 D.L.R. (4th) 193, 223 F.T.R. 137 (note), 20 C.P.C. (5th) 1, 40 Admin. L.R. (3d) 1, 2002 SCC 41, 2002 CarswellNat 822, 2002 CarswellNat 823, (sub nom. Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd v. Sierra Club of Canada) 93 C.R.R. (2d) 219, [2002] 2 S.C.R. 522 (S.C.C.)- followed Statutes considered: Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36 Generally - referred to s. 4 - considered s. 5 - considered s. 11.2 [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.2(1) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.2(4) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4 [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4(1) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.4(2) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - considered s. 11.7(2) [en. 1997, c. 12, s. 124] - referred to s. 11.51 [en. 2005, c. 47, s. 128] - considered s. 11.52 [en. 2005, c. 47, s. 128] - considered Courts ofJustice Act, R.S.O. -

Anatoliy Gruzd

ANATOLIY GRUZD, PHD Canada Research Chair in Social Media Data Stewardship, Associate Professor, Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University CV Email: [email protected] Twitter: @gruzd Research Lab: http://SocialMediaLab.ca APPOINTMENTS 2014 - present Associate Professor, Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, Canada Director, Social Media Lab 2010 - 2014 Associate Professor, School of Information Management, Faculty of Management, Dalhousie University, Canada (cross-appointment at the Faculty of Computer Science, Dalhousie University) 2009 (Fall) Adjunct Faculty, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) 2008 - 2009 Adjunct Faculty, Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto 2006 - 2008 Research Assistant, UIUC 2005 (Fall) Teaching Assistant, UIUC 2005 (Spring) Teaching Assistant, School of Management, Syracuse University 2001 - 2003 Computer Science Teacher, Lyceum of Information Technologies, Ukraine EDUCATION PhD in Library & Information Science, Graduate School of Library & Information Science 2005 – 2009 University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA) ▪ Dissertation title: Automated Discovery of Social Networks in Online Learning Communities MS in Library & Information Science, School of Information Studies 2003 – 2005 Syracuse University (Syracuse, NY, USA) BS & MS in Computer Science, Department of Applied Mathematics 1998 – 2003 Dnipropetrovsk National University (Ukraine) Graduated with Distinctions AWARDS, HONORS & GRANTS Grants ▪ eCampus Ontario Research Project ($99,959) 2017-2018 -

Relevant Stories from Library Databases

RELEVANT STORIES FROM ONLINE DATABASES Susanne Craig, Globe and Mail, 16 November 1999: The real reason Herald staff are hitting the bricks: At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity The real reason Herald staff are hitting the bricks At the bargaining table, the talk may be about money and seniority. But journalists on the picket line are fuming over what they say is the loss of their paper's integrity Tuesday, November 16, 1999 IN CALGARY -- When Dan Gaynor leaves work, he has to drive his white Jeep Cherokee past angry reporters. Rather than look at the striking employees, the publisher of The Calgary Herald tends to stare straight ahead. This is nothing new, many of the striking journalists say. They believe Mr. Gaynor's newspaper has been looking in only one direction for years. More than 200 newsroom and distribution workers at the Herald have been on strike since last Monday. They are trying to win their first union contract and, officially, they are at odds with their employer over such issues as wages and seniority rights. But ask the news hounds why they are on strike and the issues on the bargaining table never come up. Instead, they say they are angry because the Herald shapes the news, sometimes to favour a certain person or a certain point of view. -

Newspaper Topline Readership - Monday-Friday Vividata Summer 2018 Adults 18+

Newspaper Topline Readership - Monday-Friday Vividata Summer 2018 Adults 18+ Average Weekday Audience 18+ (Mon - Fri) (000) Average Weekday Audience 18+ (Mon - Fri) (000) Title Footprint (1) Print (2) Digital (3) Footprint (1) Print (2) Digital (3) NATIONAL WINNIPEG CMA The Globe and Mail 2096 897 1544 The Winnipeg Sun 108 79 46 National Post 1412 581 1022 Winnipeg Free Press 224 179 94 PROVINCE OF ONTARIO QUÉBEC CITY CMA The Toronto Sun 664 481 317 Le Journal de Québec 237 170 100 Toronto Star 1627 921 957 Le Soleil 132 91 65 PROVINCE OF QUÉBEC HAMILTON CMA La Pressea - - 1201 The Hamilton Spectator 232 183 91 Le Devoir 312 149 214 LONDON CMA Le Journal de Montréal 1228 868 580 London Free Press 147 87 76 Le Journal de Québec 633 433 286 KITCHENER CMA Le Soleil 298 200 146 Waterloo Region Record 133 100 41 TORONTO CMA HALIFAX CMA Metro/StarMetro Toronto 628 570 133 Metro/StarMetro Halifax 146 116 54 National Post 386 174 288 The Chronicle Herald 122 82 61 The Globe and Mail 597 308 407 ST. CATHARINES/NIAGARA CMA The Toronto Sun 484 370 215 Niagara Falls Review 48 34 21* Toronto Star 1132 709 623 The Standard 65 39 37 MONTRÉAL CMA The Tribune 37 21 23 24 Heures 355 329 60 VICTORIA CMA La Pressea - - 655 Times Colonist 119 95 36 Le Devoir 185 101 115 WINDSOR CMA Le Journal de Montréal 688 482 339 The Windsor Star 148 89 83 Métro 393 359 106 SASKATOON CMA Montréal Gazette 166 119 75 The StarPhoenix 105 61 59 National Post 68 37 44 REGINA CMA The Globe and Mail 90 46 56 Leader Post 82 48 44 VANCOUVER CMA ST.JOHN'S CMA Metro/StarMetro Vancouver -

F T Canwest Publishing Inc./ Publications Canwest Inc

F T CANWEST PUBLISHING INC./ PUBLICATIONS CANWEST INC., CANWEST BOOKS INC. AND CANWEST (CANADA) INC. FOURTEENTH REPORT OF FTI CONSULTING CANADA INC., IN ITS CAPACITY AS MONITOR OF THE APPLICANTS November 29, 2010 Court File No. CV-10-8533-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF CANWEST PUBLISHING INC./ PUBLICATIONS CANWEST INC., CANWEST BOOKS INC., AND CANWEST (CANADA) INC. FOURTEENTH REPORT OF FTI CONSULTING CANADA INC., in its capacity as Monitor of the Applicants November 29, 2010 INTRODUCTION 1. By Order of this Court dated January 8, 2010 (the "Initial Order"), Canwest Publishing Inc. / Publications Canwest Inc. ("CPI"), Canwest Books Inc. ("CBI"), and Canwest (Canada) Inc. ("CCI", and together with CPI and CBI, the "Applicants") obtained protection from their creditors under the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act, R.S.C. 1985 c. C-36, as amended (the "CCAA"). The Initial Order also granted relief in respect of Canwest Limited Partnership / Canwest Societe en Commandite (the "Limited Partnership", and together with the Applicants, the "LP Entities") and appointed FTI Consulting Canada Inc. ("FTI") as monitor (the "Monitor") of the LP Entities. The proceedings commenced by the LP Entities under the CCAA will be referred to herein as the "CCAA Proceedings". F T 2 TERMS OF REFERENCE 2. In preparing this report, FTI has relied upon unaudited financial information of the LP Entities, the LP Entities' books and records, certain financial information prepared by, and discussions with, the LP Entities' management. -

Biennial For

BIENNIAL REPORT 2000 – 2002 profile of COUNCIL The Council of Ontario Universities (COU) represents the collective interests of Ontario’s 17 member universities and two associate members. The organiza- tion was formed under the original name of the Committee of Presidents of the Universities of Ontario in 1962 in response to a need for institutional participa- tion in educational reform and expansion. COU’s mandate is to provide leadership on issues facing the provincially funded universities, to participate actively in the development of relevant public policy, to communicate the contribution of higher education in the province of Ontario and to foster co-operation and understanding among the universities, related interest groups, the provincial government and the general public. The Council consists of two representatives from each member institution: the executive head (president, principal or rector) and a colleague appointed by each institution’s senior academic governing body. It meets five times during the academic year and is supported by the Executive Committee, which, in turn, is supported by a full-time secretariat that provides centralized service functions. Over 50 affiliates, special task forces, committees and other groups also support and work toward the achievement of Council’s objectives. MEMBER INSTITUTIONS Brock University Carleton University University of Guelph Lakehead University Laurentian University McMaster University Nipissing University University of Ottawa Queen’s University Ryerson University University of -

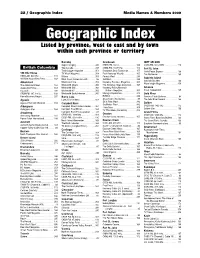

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

September 11, 2018 7:00 P.M

The Niagara Catholic District School Board through the charisms of faith, social justice, support and leadership, nurtures an enriching Catholic learning community for all to reach their full potential and become living witnesses of Christ. AGENDA AND MATERIAL COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MEETING TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2018 7:00 P.M. FATHER KENNETH BURNS, C.S.C. BOARD ROOM CATHOLIC EDUCATION CENTRE, WELLAND, ONTARIO A. ROUTINE MATTERS 1. Opening Prayer – Trustee Burtnik - 2. Roll Call - 3. Approval of the Agenda - 4. Declaration of Conflict of Interest - 5. Approval of Minutes of the Committee of the Whole Meeting - 5.1 June 12, 2018 A5.1 5.2 June 20, 2018 A5.2 6. Consent Agenda Items - 6.1 Architect Selection for Monsignor Clancy Catholic Elementary School and A6.1 Our Lady of Mount Carmel Catholic Elementary School 6.2 Staff Development Department Professional Development Opportunities A6.2 6.3 In Camera Items F1.1, F1.2 and F4 - B. PRESENTATIONS C. COMMITTEE AND STAFF REPORTS 1. Director of Education and Senior Staff Introduction to the 2018-2019 School Year C1 2. Provisions of Special Education Programs and Services - Special Education Plan C2 3. Niagara Compliance Audit Committee Report C3 4. Monthly Updates 4.1 Student Senate Update - 4.2 Senior Staff Good News Update - D. INFORMATION 1. Trustee Information 1.1 Spotlight on Niagara Catholic – June 19, 2018 D1.1 1.2 Calendar of Events – September 2018 D1.2 2 1.3 Ontario Legislative Highlights – June 22, 2018, July & August 2018 D1.3 1.4 Letter to Parents and Guardians – September 2018 D1.4 1.5 Niagara Foundation for Catholic Education Golf Tournament – September 19, 2018 D1.5 1.6 OCSTA 2018 Fall Regional Meeting – September 26, 2018 D1.6 1.7 OCSTA 2018 Fall Regional Meeting Questions for Discussion D1.7 E.