Play Chapter: Video Games and Transmedia Storytelling 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding and Memory in Star Wars Comics William Proctor Since at least the turn of the twentieth century, the comic book medium has grown in dialogue alongside other media forms, both old and new, underscored by what is commonly described as adaptation. In basic terms, adaptation refers to a process whereby stories are lifted from one medium and replanted in another. Of course, the process is more complicated than that as different media each bring different creative requirements and, as a result, adaptation is never simply about reproducing a story in exactly the same way—although it is about reproduction, to some degree. Put simply, adaptation refers to the retelling of a story in a new media location. For example, each installment of Warner Bros.’ Harry Potter film series—from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows—are adaptations of novels written by J.K Rowling, each ‘retelling’ the same story in the process from book-to-film. The caveat here is that such a retelling also involves revising narrative elements, and even editing or reframing scenes from the ‘source’ text to better-fit the ‘target’ medium. Variations as well as repetition are key factors to consider, as adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon notes (2006). The contemporary landscape is brimming with adaptations of all sorts, but perhaps the most common example in the twenty-first century are the bevvy of film and TV series based on comic books, many of them produced by the ‘big two’ superhero publishers, Marvel and DC, as film scholar Terence McSweeney argues: “We are living in the age of the superhero and we cannot deny it” (2018, 1). -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Document 273 5-5-2014 – Download

Case 2:07-cv-00552-DB-EJF Document 273 Filed 05/05/14 Page 1 of 46 PROSE 1 SOPHIA STEWART P.O. BOX 31725 2 Las Vegasl NV 89173 3 702-501-5900 (PH) 4 ... IN PROPRIA PERSONA v: ---;;:\-CQ\( 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT \l~YU I I "' 6 FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH 7 SOPHIA STEWART, HON. EVELYN J. FURSE 8 Plaintiff, v. HON. DEE BENSON 9 MICHAEL STOLLER, GARY BROWN, Case No.: 2:07CV552 DB-EJF 10 DEAN WEBB, AND JONATHAN 11 LUBELL OBJECTION TO COURT DENIAL Defendants. TO AWARD DAMAGES AGAINST 12 DEFENDANT LUBELL AND 13 DEMAND FOR EXPEDITED AWARD 14 15 16 COMES NOW1 PLAINTIFF SOPHIA STEWART1 bringing forth the Objection To the 17 Court's Denial To Award Damages Against All Defendants And Demand For 18 Expedited Award of Damages in the amount of One Billion Three Hundred and 19 Sixty Seven Million $1,367,000,000.00 dollars for The Matrix Trilogy damages and 20 Three point five Billion $3,580,000,000.00 dollars in damages for the Terminator 21 Franchise Series. 22 23 Plaintiff brings forth this objection against the court for violating the 24 Plaintiff's constitutional Sixth and fourth amendments "Due Process and Equal 25 Protection" rights and obstructing her from a jury trial and the ability to face the 26 defendants in court for more than 6 years while Jonathan Lubell was deceased, 27 thus constituting a violation of racial discrimination and fraud. Racial 28 discrimination by concerted action is a federal offense under 18 U.S.C. -

Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book

PENNY ARCADE: VOLUME 8: MAGICAL KIDS IN DANGER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Krahulik,Jerry Holkins | 112 pages | 11 Sep 2012 | Oni Press,US | 9781620100066 | English | Portland, United States Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book The wares of the poor little match girl illuminate her cold world, bringing some beauty to her brief, tragic life. He has a fascination with unicorns , a secret love of Barbies , is a dedicated fan of Spider-Man and Star Wars , and has proclaimed " Jessie's Girl " to be the greatest song of all time. Thompson proceeded to phone Krahulik, as related by Holkins in the corresponding news post. The transformation of humanity through nano… More. PC Gamer. Jul 09, Kevin Gentilcore rated it really liked it. Anyway, people probably already know whether or not they like Penny Arcade. Retrieved March 23, Retrieved May 10, Unless you are a major geek like me, you have no idea what Penny Arcade is. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 26, Retrieved May 9, The comics are from , the commentary from , and both are reflecting an industry that moves rapidly, so both are often unintentionally humorous just in regards to how things have fallen out since. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. He has just enough fuel to reach the planet—then he finds that he has a sto… More. Some of these works have been included with the distribution of the game, and others have appeared on pre-launch official websites. Good collection, quick read. Published September 11th by Oni Press first published August 29th Want to Read Currently Reading Read. -

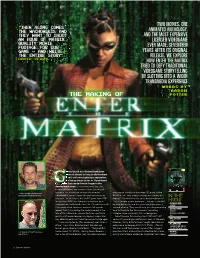

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World Across Distinct Media and Environments

Transmedia Practice: Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World across Distinct Media and Environments by Christy Dena A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Letters, Art and Media Department of Media and Communications Digital Cultures Program University of Sydney Australia Supervisor: Professor Gerard Goggin Associate Supervisor: Dr. Chris Chesher Associate Supervisor: Dr. Anne Dunn 2009 Let’s study, with objectivity and curiosity, the mutation phenomenon of forms and values in the current world. Let’s be conscious of the fact that although tomorrow’s world does not have any chance to become more fair than any other, it owns a chance that is linked to the destiny of the current art [...] that of embodying, in their works some forms of new beauty, which will be able to arise only from the meet of all the techniques. (Francastel 1956, 274) Translation by Regina Célia Pinto, emailed to the empyre mailing list, Jan 2, 2004. Reprinted with permission. To the memory of my dear, dear, mum, Hilary. Thank you, for never denying yourself the right to Be. ~ Transmedia Practice ~ Abstract In the past few years there have been a number of theories emerge in media, film, television, narrative and game studies that detail the rise of what has been variously described as transmedia, cross-media and distributed phenomena. Fundamentally, the phenomenon involves the employment of multiple media platforms for expressing a fictional world. To date, theorists have focused on this phenomenon in mass entertainment, independent arts or gaming; and so, consequently the global, transartistic and transhistorical nature of the phenomenon has remained somewhat unrecognised. -

Entertainment Architecture

Entertainment Architecture Constructing a Framework for the Creation of an Emerging Transmedia Form by Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Dipl.-Kfm. European Business School, Oestrich-Winkel, Germany A dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Entertainment Architecture Keywords film movie transmedia entertainment transmedia storytelling pervasive games ubiquitous games agency form evolution entrepreneurship business industry creative destruction marketing promotion — II — Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Entertainment Architecture Abstract This thesis investigates the radically uncertain formal, business, and industrial environment of current entertainment creators. It researches how a novel communication technology, the Internet, leads to novel entertainment forms, how these lead to novel kinds of businesses that lead to novel industries; and in what way established entertainment forms, businesses, and industries are part of that process. This last aspect is addressed by focusing on one exemplary es- tablished form: movies. Using a transdisciplinary approach and a combination of historical analysis, industry interviews, and an innovative mode of ‘immersive’ textual analysis, a coherent and comprehensive conceptual framework for the creation of and re- search into a specific emerging entertainment form is proposed. That form, -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse

religions Article A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse Rachel Wagner Department of Philosophy and Religion, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Here I build upon Robert Orsi’s work by arguing that we can see presence—and the longing for it—at work beyond the obvious spaces of religious practice. Presence, I propose, is alive and well in mediated apocalypticism, in the intense imagination of the future that preoccupies those who consume its narratives in film, games, and role plays. Presence is a way of bringing worlds beyond into tangible form, of touching them and letting them touch you. It is, in this sense, that Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion with a “new visibility” that is much more than “simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more.” I propose that the “new awareness of religion” they posit includes the mediated worlds that enchant and empower us via deeply immersive fandoms. Whereas religious institutions today may be suspicious of presence, it lives on in the thick of media fandoms and their material manifestations, especially those forms that make ultimate promises about the world to come. Keywords: apocalypticism; Orsi; enchantment; fandom; video games; pervasive games; cowboy; larp; West 1. Introduction Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion today with a “new visibility” that is “far more complex and nuanced than simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more” (Hoelzl and Ward 2008, p. -

A Rundown of What's Going on with Penny Arcade

12/27/2014 A Rundown of What’s Going on with Penny Arcade Now | A Rundown of What’s Going on with Penny Arcade Now Posted on June 20, 2013 by Tami Baribeau It hasn’t been that long since the last time Penny Arcade did something that cast the company in a negative light, but here we are again with another fiasco that’s been making its way around Twitter today. I thought it would be helpful to do a quick rundown of the events from today to make everyone aware of the situation and help answer some questions about why you might want to rethink supporting Penny Arcade, PAX, or anything affiliated with that organization. It all started today when this panel was posted from PAX Australia, titled “Why So Serious? Has the Industry Forgotten That Games Are Supposed to Be Fun?”. The original screencap of the description is below. “Why does the game industry garner such scrutiny from outside sources and within? Every point aberration gets called into question, reviewers are constantly criticised and developers and publishers professionally and personally attacked. Any titillation gets called out as sexist or misogynistic and involve any antagonist race other than Anglo-Saxons and you’re a racist. It’s gone too far and when will it all end? How can we get off the soapbox and work together to bring a new constructive age into fruition?” There is so much wrong with this panel description that I don’t even know where to begin. The idea that games as a medium are exempt from criticism because they’re “supposed to be fun” is ridiculous and immature. -

Breaking the Code of the Matrix; Or, Hacking Hollywood

Matrix.mss-1 September 1, 2002 “Breaking the Code of The Matrix ; or, Hacking Hollywood to Liberate Film” William B. Warner© Amusing Ourselves to Death The human body is recumbent, eyes are shut, arms and legs are extended and limp, and this body is attached to an intricate technological apparatus. This image regularly recurs in the Wachowski brother’s 1999 film The Matrix : as when we see humanity arrayed in the numberless “pods” of the power plant; as when we see Neo’s muscles being rebuilt in the infirmary; when the crew members of the Nebuchadnezzar go into their chairs to receive the shunt that allows them to enter the Construct or the Matrix. At the film’s end, Neo’s success is marked by the moment when he awakens from his recumbent posture to kiss Trinity back. The recurrence of the image of the recumbent body gives it iconic force. But what does it mean? Within this film, the passivity of the recumbent body is a consequence of network architecture: in order to jack humans into the Matrix, the “neural interactive simulation” built by the machines to resemble the “world at the end of the 20 th century”, the dross of the human body is left elsewhere, suspended in the cells of the vast power plant constructed by the machines, or back on the rebel hovercraft, the Nebuchadnezzar. The crude cable line inserted into the brains of the human enables the machines to realize the dream of “total cinema”—a 3-D reality utterly absorbing to those receiving the Matrix data feed.[footnote re Barzin] The difference between these recumbent bodies and the film viewers who sit in darkened theaters to enjoy The Matrix is one of degree; these bodies may be a figure for viewers subject to the all absorbing 24/7 entertainment system being dreamed by the media moguls.