IN the MATTER the Resource Management Act 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments from Heritage New Zealand

Comment on the Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Fast Track Application 1. Contact Details Please ensure that you have authority to comment on the application on behalf of those named on this form. Organisation name (if relevant) Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga *First name Susan *Last name Andrews Postal address PO Box 105 291, Auckland City 1143 *Home phone / Mobile phone 027 202 3935 *Work phone 09 307 9940 *Email (a valid email address [email protected] enables us to communicate efficiently with you) 2. *We will email you draft conditions of consent for your comment about this application I can receive emails and my email address is I cannot receive emails and my postal address is ✓ correct correct 3. Please provide your comments on the Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Application If you need more space, please attach additional pages. Please include your name, page numbers and Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Application on the additional pages. Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Page 3 of 7 1. Archaeology The archaeological assessment of the subject site prepared by Clough & Associates in 2015, updated in August 2019, appears not to consider the possibility that terraces (which they identify as natural) located within the south western portion of the site may be an extension of archaeological site R11/1196 (terraces with a stone artefact) and that subsurface archaeological remains relating to Maori settlement on the terraces may be present. (See New Zealand Archaeological Authority ArchSite database extract and annotated 1940 aerial below). Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Page 4 of 7 This possible connection was established following a survey of the site completed by Russell Foster in September 2015 for an assessment for the Glen Innes to Tamaki Drive Shared Path1, which resulted in relocation of R11/1196, previously located some 170 metres to the south of the subject property, to a location now only 70 metres south of the subject property. -

South & East Auckland

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R BAY RD R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O D Island Haven I R R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WA Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W A R R K ONEWA L HaurakiMotorway . -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Statement of Evidence in Chief of Anthony David Cross on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 10 May 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] Introduction 1. My full name is Anthony David Cross. I currently hold the position of Network Development Manager in the AT Metro (public transport) division of Auckland Transport (AT). 2. I hold a Bachelor of Regional Planning degree from Massey University. 3. I have 31 years’ experience in public transport planning. I worked at Wellington Regional Council between 1986 and 2006, and the Auckland Regional Transport Authority between 2006 and 2010. I have held my current role since AT was established in 2010. 4. In this role, I am responsible for specifying the routes and service levels (timetables) for all of Auckland’s bus services. Since 2012, I have led the AT project known as the New Network, which by the end of 2018 will result in a completely restructured network of simple, connected and more frequent bus routes across all of Auckland. -

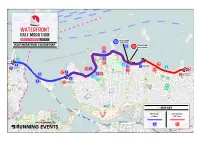

Waterfront-Course-Map-21K.Pdf

de W Auckland Devonport to Rangitoto Island Devonport Wharf Bean Rock Waiheke A uckl a nd - W a ihek e Ferry e Fe Waihek Auckland - Auckland r t ry o Pineharbour Devonpor akapuna Auckland to Coromandel t -T West Bastion Auckland to Coromandel y Reef Auckland to Pineharbour Auckland - Half Moon Bay East Bastion Reef START LINE TAMAKI DRIVE HALF MARATHON COURSE MAP 11 FINISH LINE 12 km SELWYN RESERVE km Orakei Wharf rive i D k 1 a km m Ta 7 Takaparawhau a St an r pi m eet Michael Point Ha Joseph Savage 9 Memorial km Park 7 Selwyn Domain ay 6 Ta Okahu w Tamaki ma le Dr ive Cycleway ki 16 yc Tamaki D Dri Bay e C v temata km mak i Driv e i Ta 20 Judges a Selwyn Av rive Gl 5 W Mar TURNAROUND #2 km a au d C t e s Bay r km escent esce n nue ton Orakei 10 Marau Cr FIRST LAP TURNAROUND #1 Marina km e e Ro FIRST LAP 13 2 t Mission Bay Eltham Road a e Kohimarama 19 e 7 d km km r ve t Avenu 18 ri 17 km S Tagal ad Road Beach i D n k a km Ronaki Road km a n m a so a venue o T A 14 3 e T oad 6 e Cyc am R iv lew T aki Dri km km ay em Rukutai Str ar ve Cyc t y Dr i anaki Road TURNAROUND #4 a Bridge ki Tamaki Patt gate Road a K Road l eet B Dr 8 15 d s 4 m ive tr wa a a e S g T 7 km km Ho o SECOND LAP d nue R e Ju te km ad e v r Road nt lwick T l v o Ku ama S ri aur Watene esce p W u Auckland ee ill Cr A e mar D eet Ni h N C i i a p h g Saint Stephens n o ar t ihil ht Road en Reserve e Str K Hanene e t u C Sage R Cr Ta Ta i Drive re l Cr The a s Long a T e m m it cent s r Titai Str t Reihana Str eet t escent c a a 7 Selwy a e eet Rota Place e ki ki D e -

South & East Auckland Auckland Airport

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O Island Haven I RD R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WAR BAY RD Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W R A L R Hauraki Gulf I MOKO ONEWA R P IA RD D D Waitemata A HINEMOA ST Waiheke LLE RK Taniwhanui Point W PA West Harbour OLD LAKE Golf Course Pakatoa Point L E ST Chatswood BAYSWATER VAUXHALL RD U 1 Harbour QUEEN ST Bayswater RD Narrow C D Motuihe KE NS R Luckens Point Waitemata Neck Island AWAROA RD Chelsea Bay Golf Course Park Point Omiha Motorway . -

Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in Part 1 6300 North Auckland Railway Line

Designation Schedule – KiwiRail Holdings Ltd Number Purpose Location 6300 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, North Auckland Railway Line from Portage railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Road, Otahuhu to Ross Road, Topuni 6301 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Newmarket Branch Railway Line from Remuera railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Road, Newmarket to The Strand, Parnell 6302 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, North Island Main Trunk Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... from Buckland to Britomart Station, Auckland Central 6303 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Avondale Southdown Railway Line from Soljak railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Place, Mount Albert to Bond Place, Onehunga 6304 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Onehunga Branch Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises from Onehunga Harbour Road, Onehunga to ... Station Road, Penrose and Neilson Street, Tepapa 6305 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Southdown Freight Terminal at Neilson Street railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... (adjoins No. 345), Onehunga 6306 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Mission Bush Branch Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... from Mission Bush Road, Glenbrook to Paerata Road, Pukekohe 6307 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Manukau Rail Link from Lambie Drive (off- railway -

Penrose.DOC 2

Peka Totara Penrose High School Golden Jubilee 1955 –2005 Graeme Hunt Inspiration from One Tree Hill The school crest, a totara in front of the obelisk marking the grave of ‘father of Auckland’ Sir John Logan Campbell on One Tree Hill (Maungakiekie), signals the importance of the pa and reserve to Penrose High School. It was adopted in 1955 along with the Latin motto, ‘Ad Altiora Contende’, which means ‘strive for higher things’. Foundation principal Ron Stacey, a Latin scholar, described the school in 1955 as a ‘young tree groping courageously towards the skies’. ‘We look upward towards the summit of Maungakiekie where all that is finest in both Maori and Pakeha is commemorated for ever in stone and bronze,’ he wrote. In 1999 a red border was added to the crest but the crest itself remained unchanged. In 1987 the school adopted a companion logo based on the kiekie plant which grew on One Tree Hill in pre-European times (hence the Maungakiekie name). The logo arose from a meeting of teachers debating education reform where the school’s core values were identified. The words that appear on the kiekie logo provide a basis for developing the school’s identity. The kiekie, incorporated in the school’s initial charter in 1989, does not replace the crest but rather complements it. School prayer† School hymn† Almighty God, our Heavenly Father, Go forth with God! We pray that you will bless this school, Go forth with God! the day is now Guide and help those who teach, and those who learn, That thou must meet the test of youth: That together, we may seek the truth, Salvation's helm upon thy brow, And grow in understanding of ourselves and other people Go, girded with the living truth. -

Tamaki Yacht Club at Bastion Point, Orākei - Request for Comment from Te Runanga O Ngati Whatua

10/30/2019 Gmail - Tamaki Yacht Club at Bastion Point, Orākei - request for comment from Te Runanga o Ngati Whatua Ross Roberts <[email protected]> Tamaki Yacht Club at Bastion Point, Orākei - request for comment from Te Runanga o Ngati Whatua 1 message Ross Roberts <[email protected]> 30 October 2019 at 17:05 To: [email protected] Cc: [email protected], Tamaki <[email protected]> Tēnā koutou, I am Ross Roberts, the Commodore of Tamaki Yacht Club. A a keen sailor from England, I moved to New Zealand in 2008 to enjoy the fantastic marine environment in Auckland which is world-renowned for its sailing. When not sailing I work as an engineering geologist trying to manage the social and environmental effects of natural processes such as landslides and volcanic eruptions. I am writing to start a discussion with you about possible future plans for Tamaki Yacht Club, the sailing club at Bastion Point between Mission Bay and Ōkahu Bay. Tamaki Yacht Club was founded around the time that Tamaki Drive was opened in 1932, and has been a centre for small sailing yachts ever since. We are a small club that is mainly used by more experienced sailors for casual racing, because the slipway is quite exposed so the club is not particularly well suited for learners. The clubhouse was built when the club was founded, and was slightly expanded in 1972 at the front, in the former location of a gun turret that protected the entrance to the Waitematā during the war. -

Key Issues Report for New Zealand Transport Agency, East West Link

Key issues report for New Zealand Transport Agency, East West Link Prepared under section 149G of the Resource Management Act 1991 Date: 14 February 2017 Report by: Auckland Council (Local Authority) Prepared for: Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) East West Link key issues report for Environmental Protection Authority, February 2017, Auckland Council 2 Contents Glossary ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Purpose and scope ....................................................................................................................... 5 Separation of roles ........................................................................................................................ 5 Proposal overview ......................................................................................................................... 5 Local context ................................................................................................................................. 6 Physical environment .................................................................................................................... 6 Existing authorisations .................................................................................................................. 7 Existing authorisations associated -

Rail Level Crossing Grade Separation Feasibility Study

Rail Level Crossing Grade Reference: 236852 Prepared for: Auckland Separation Feasibility Study Transport Final Report – Volume 1 Revision: 07 12 December 2014 Project 236852 File AT Level Crossing Report_V7.docx 12 December 2014 Revision 07 Document control record Document prepared by: Aurecon New Zealand Limited Level 4, 139 Carlton Gore Road Newmarket Auckland 1023 PO Box 9762 Newmarket Auckland 1149 New Zealand T +64 9 520 6019 F +64 9 524 7815 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Document control Report title Final Report – Volume 1 Document ID Project number 236852 File path Client Auckland Transport Client contact Andrew Firth Rev Date Revision details/status Prepared by Author Verifier Approver 0 31 July 2013 Draft for AT to comment T Pang T Pang A Mein 1 30 August 2013 AT comments included T Pang T Pang L Beban A Mein 2 2 September 2013 Draft for AT to Review T Pang T Pang A Mein A Mein Final Pilot Report as Agreed by 3 3 November 2013 T Pang T Pang A Mein A Mein AT Draft Full Report for AT to J Atuluwage/ 4 11 February 2014 T Pang A Mein A Mein Comment T Pang 5 13 October 2014 Final Report T Pang T Pang A Mein A Mein T Pang/S 6 25 November 2014 Final Report T Pang A Mein A Mein Lalpe 7 12 December 2014 Final Report S Lalpe T Pang A Mein -

Tamaki Drive Walking Trail Existing Signage Audit

Tamaki Drive Walking Trail Existing Signage Audit Start at The Landing Okahu Bay – Western Entrance to Achilles Point via Michael Joseph Savage Memorial (Direction: West to East) Site & Sign Ref No. The Landing Okahu Bay – Western Entrance, Orakei Marina (Image) Tamaki Drive The large sign is located in Orakei Marina before the Auckland Sailing Club on Section 1_xx Section 1.1 The Tamaki Drive. It is placed on the western entrance of the Orakei Marina. This is Landing Okahu Bay an informational sign coloured in blue (re-branded by the Auckland Council). It is located on the ground off the footpath. The sign is double sided with the same information in both sides. The pictures are shown below. The orange rectangle indicates the location of the sign. Existing signage The sign is in an excellent condition. Different branding to other existing signs (comment) as the colour is light blue instead of dark green. Enhancements / The sign is in an excellent condition. No repair needed. additions / repairs needed Site & Sign Ref No. The Landing Okahu Bay – map (Image) Tamaki Drive The sign is located in Orakei Marina before the Auckland Sailing Club on Tamaki Section 1_xx Section 1.1 The Drive. This is an informational sign coloured in blue. The location of this map is Landing Okahu Bay on the parking entrance on the west part of The Landing Okahu. It is located on the ground off the footpath. The sign is double sided with the same information in both sides. The pictures are shown below. The orange rectangle indicates the location of the sign. -

2 Tamaki Drive Precinct Scope

Tamaki Drive Precinct Event Guidelines Ōrākei Local Board Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 2 Tamaki Drive Precinct scope ........................................................................................ 5 3 Event permit requirements ............................................................................................ 6 4 Roles and Responsibilities ............................................................................................ 6 5 St Heliers Bay Reserve: Vellenoweth Green ................................................................. 7 6 Local Consultation ......................................................................................................... 7 7 Local suppliers and traders ........................................................................................... 8 8 Tamaki Drive Precinct road closures ............................................................................. 8 9 Events involving planned noise ..................................................................................... 9 10 Signage ......................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1 – Event facilitation process ............................................................................. 11 Appendix 2 – Facilitation stakeholders............................................................................... 13 Appendix