Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Orakei Claim (Wai-9)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myth of Cession: Public Law Textbooks and the Treaty of Waitangi

EMILY BLINCOE THE MYTH OF CESSION: PUBLIC LAW TEXTBOOKS AND THE TREATY OF WAITANGI LLB (HONS) RESEARCH PAPER LAWS 522: PUBLIC LAW: STATE, POWER AND ACCOUNTABILITY FACULTY OF LAW 2015 2 Table of Contents I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 4 II THE TREATY WAS NOT A CESSION OF SOVEREIGNTY ...................................... 7 A Not Possible to Cede Sovereignty in Māori Law ......................................................... 8 B Context and Motivations for the Treaty and te Tiriti ................................................. 9 C Meaning of the Text and Oral Discussions ................................................................ 14 D Aftermath – How Did the Crown Acquire Sovereignty? ......................................... 20 III PUBLIC LAW TEXTBOOKS AS A SUBJECT OF CRITIQUE ................................ 22 A Introduction to the Public Law Textbooks ................................................................ 22 B Textbooks as a Subject of Critique ............................................................................. 23 IV THE TEXTBOOKS .......................................................................................................... 26 A The Myth that the Treaty Was a Cession of Sovereignty ......................................... 27 B Failure to Engage with Māori History, Law and Motivations ................................. 30 C Downplaying of Textual Differences and English Text as “the” Treaty ................ -

Crucified God Tells Us to Love

MARCH 2008 APRIL 2016 CrucifiedCrucified GodGod tellstells usus toto lovelove Susan Thompson with her photographs of crosses from the Church of the Mortal Agony of Christ at Dachau (left) and the Chapel of San Damiano in Assisi. he cross as a symbol of dated and distasteful in its with the suffering of the world visited churches, museums and Susan says a visit to the love and solidarity with emphasis on sacrifice. Some and even shares in its pain. galleries where they saw lots of Dachau Concentration Camp those who suffer was the women saw the cross as a “Like Moltmann, I was crosses. She says some were was the most sobering message of an Easter symbol of violence reflecting the particularly touched by the cry elaborately beautiful, others were experience of the trip. exhibition of nature of patriarchy,” she says. of abandonment voiced by the starkly plain but they all made The cross in the Church of photographs in “I agreed with some of these dying Jesus in the gospel of her pause and reflect. Hamilton. sentiments, but was also drawn Mark: 'My God, why have you A special place they visited the Mortal Agony of Christ at TThe photos were by to the cross. forsaken me?' As an adopted was the Chapel of San Damiano Dachau is raw and haunting. This Methodist Waikato-Waiariki “At that time I was struggling person I was familiar with deep- in Assisi. According to tradition, Christ is a skeleton made of iron, Synod superintendent Rev Dr with my own dilemmas. I was a seated feelings of rejection.” this was where St Francis was hollowed out and starving, the Susan Thompson. -

Treaty Rights in the Waitangi Tribunal

© New Zealand Centre for Public Law and contributors Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand December 2010 The mode of citation of this journal is: (2010) 8 NZJPIL (page) The previous issue of this journal is volume 8 number 1, June 2010 ISSN 1176-3930 Printed by Geon, Brebner Print, Palmerston North Cover photo: Robert Cross, VUW ITS Image Services CONTENTS Judicial Review of the Executive – Principled Exasperation David Mullan .......................................................................................................................... 145 Uncharted Waters: Has the Cook Islands Become Eligible for Membership in the United Nations? Stephen Smith .......................................................................................................................... 169 Legal Recognition of Rights Derived from the Treaty of Waitangi Edward Willis.......................................................................................................................... 217 The Citizen and Administrative Justice: Reforming Complaint Management in New Zealand Mihiata Pirini.......................................................................................................................... 239 Locke's Democracy v Hobbes' Leviathan: Reflecting on New Zealand Constitutional Debate from an American Perspective Kerry Hunter ........................................................................................................................... 267 The Demise of Ultra Vires in New Zealand: -

Routes Orakei Mission Bay St Heliers Glendowie Fare Zones & Boundaries

Orakei Routes Fare Zones Tāmaki Glen Innes, St Heliers, Mission Bay, Tamaki Dr, Britomart Mission Bay Link & Boundaries 744 Panmure, Pilkington Rd, Glen Innes, Mt Taylor Dr, St Heliers Glen Innes, West Tamaki Rd, Eastridge, Orakei, Britomart 762 Wellsford St Heliers 774 Mt Taylor Dr, Long Dr, Mission Bay, Tamaki Dr, Britomart Omaha (Monday to Friday peak only) Matakana 775 Glendowie, St Heliers, Mission Bay, Tamaki Dr, Britomart Glendowie (Monday to Friday peak only) Warkworth 781 Mission Bay, Orakei, Victoria Ave, Newmarket, Auckland Museum 782 Sylvia Park, Mt Wellington, Ellerslie, Grand Dr, Meadowbank, Warkworth Southern Bus Timetable Eastridge, Mission Bay 783 Eastern Bays Loop clockwise: St Heliers, Glendowie, Eastridge, Kupe St, Mission Bay, St Heliers Waiwera Helensville Hibiscus Coast Your guide to buses in this area 783 Eastern Bays Loop anticlockwise: St Heliers, Mission Bay, Orewa Wainui Kupe St, Eastridge, Glendowie, St Heliers Kaukapakapa Hibiscus Coast Gulf Harbour Waitoki Upper North Shore Other timetables available in this area that may interest you Albany Waiheke Timetable Routes Constellation Lower North Shore Riverhead Hauraki Gulf Tāmaki Link CityLink, InnerLink, OuterLink, TāmakiLink Takapuna Rangitoto Island Huapai Westgate Link Central Isthmus City Isthmus 66, 68, 650, 670 Waitemata Crosstowns Harbour Britomart Swanson Kingsland Newmarket Beachlands Remuera Rd, Meadowbank, Henderson 75, 650, 747, 751, 755, 781, 782 St Johns, Stonefields Waitakere Panmure New Lynn Waitakere Onehunga 744 762 774 Mt Wellington, 32, -

Letter Template

ATTACHMENT 5 Geological Assessment (Tonkin & Taylor) Job No: 1007709 10 January 2019 McConnell Property PO Box 614 Auckland 1140 Attention: Matt Anderson Dear Matt Orakei ONF Assessment 1- 3 Purewa Rd, Meadowbank Introduction McConnell Property is proposing to undertake the development of a multi-story apartment building at 1 - 3 Purewa Road, Meadowbank. The property is located within an area covered by the Outstanding Natural Feature (ONF) overlay of the Auckland Unitary Plan. The overlay relates to the Orakei Basin volcano located to the west of the property. The ONF overlay requires consent for the earthworks and the proposed built form associated with the development of the site. McConnell Property has commissioned Tonkin & Taylor Ltd (T+T) to provide a geological assessment of the property with respect to both the ONF overlay and the geological characteristics of the property. The purpose of the assessment is to place the property in context of the significant geological features identified by the ONF overlay, and to assess the geological effects of the proposed development. Proposed Development The proposal (as shown in the architectural drawings appended to the application) is to remove the existing houses and much of the vegetation from the site, and to develop the site with a new four- storey residential apartment building with a single-level basement for parking. The development will involve excavation of the site, which will require cuts of up to approximately 6m below existing ground level (bgl). The cut depths vary across the site, resulting in the average cut depth being less than 6m bgl. Site Description The site is located at the end of the eastern arm of the ridgeline that encloses the Orakei Basin (Figure 1). -

Your Cruise Natural Treasures of New-Zealand

Natural treasures of New-Zealand From 1/7/2022 From Dunedin Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 1/18/2022 to Auckland On this cruise, PONANT invites you to discover New Zealand, a unique destination with a multitude of natural treasures. Set sail aboard Le Lapérouse for a 12-day cruise from Dunedin to Auckland. Departing from Dunedin, also called the Edinburgh of New Zealand, Le Lapérouse will cruise to the heart of Fiordland National Park, which is an integral part of Te Wahipounamu, UNESCOa World Heritage area with landscapes shaped by successive glaciations. You will discoverDusky Sound, Doubtful Sound and the well-known Milford Sound − three fiords bordered by majestic cliffs. The Banks Peninsula will reveal wonderful landscapes of lush hills and rugged coasts during your call in thebay of Akaroa, an ancient, flooded volcano crater. In Picton, you will discover the Marlborough region, famous for its vineyards and its submerged valleys. You will also sail to Wellington, the capital of New Zealand. This ancient site of the Maori people, as demonstrated by the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum, perfectly combines local traditions and bustling nightlife. From Tauranga, you can discover the many treasuresRotorua of : volcanoes, hot springs, geysers, rivers and gorges, and lakes that range in colour from deep blue to orange-tinged. Then your ship will cruise towards Auckland, your port of disembarkation. Surrounded by the blue waters of the Pacific, the twin islands of New Zealand are the promise of an incredible mosaic of contrasting panoramas. The information in this document is valid as of 9/24/2021 Natural treasures of New-Zealand YOUR STOPOVERS : DUNEDIN Embarkation 1/7/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 1/7/2022 at 6:00 PM Dunedin is New Zealand's oldest city and is often referred to as the Edinburgh of New Zealand. -

TE POU O KĀHU PŌKERE Iwi Management Plan for Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei 2018 Te Pou O Kāhu Pōkere

TE POU O KĀHU PŌKERE Iwi Management Plan for Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei 2018 Te Pou o Kāhu PōKere Ngā Wāhanga o te Mātātaki reflect the stages that Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei go through when laying a challenge. This is commonly referred to as a wero. This document is a wero, a challenge, to work together to better understand the views, perspectives and priorities of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei in relation to resource management matters. The name of this plan is taken from one of the wāhanga (stages) of the mātātaki (challenge). This is called Te Pou o Kāhu Pōkere. The Kāhu Pōkere is the black hawk and is a central figure on the front of our whare tupuna, Tumutumuwhenua. It is a cultural legacy of the hapū and symbolises kaitiakitanga which is the underlying principle of this work. The purpose of this stage and for Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei is to personify the role of the Kāhu Pōkere. It is elevated and holds dominion to protect those in its care, to look out to the distance, traversing and understanding ones domain and ascertaining the intention of others. Inherent in this stage and in this document is action, movement, focus and to be resolute with clarity and purpose. Te Pou o Kāhu Pōkere is a recognised iwi planning document for the purposes of the Resource Management Act 1991. CoNTeNTs RĀRANGI KŌRERO RĀRANGI KŌRERO (CoNTeNTS) ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 KuPu WhAKATAKI (FOREWORD) ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 FROM THE MAYOR oF AuCKLAND -

522 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

522 bus time schedule & line map 522 Schools View In Website Mode The 522 bus line (Schools) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Schools: 7:10 AM - 7:16 AM (2) Schools: 3:35 PM - 3:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 522 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 522 bus arriving. Direction: Schools 522 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Schools Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:10 AM - 7:16 AM Stop B St Heliers 413 Tamaki Drive, Auckland Tuesday 7:10 AM - 7:16 AM Opp 81 St Heliers Bay Rd Wednesday 7:10 AM - 7:16 AM Saint Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Thursday 7:10 AM - 7:16 AM 124 St Heliers Bay Rd Friday Not Operational 124 St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Saturday Not Operational Opp 151 St Heliers Bay Rd 151A St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Opp 183 St Heliers Bay Rd 183 St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland 522 bus Info Direction: Schools 222 St Heliers Bay Rd Stops: 42 2 Ashby Avenue, Auckland Trip Duration: 50 min Line Summary: Stop B St Heliers, Opp 81 St Heliers 260 St Heliers Bay Rd Bay Rd, 124 St Heliers Bay Rd, Opp 151 St Heliers 260A St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Bay Rd, Opp 183 St Heliers Bay Rd, 222 St Heliers Bay Rd, 260 St Heliers Bay Rd, 320 St Heliers Bay Rd, 320 St Heliers Bay Rd 358 St Heliers Bay Rd, 299 Kohimarama Rd, 255 320 St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Kohimarama Rd, Kohimarama Rd Opp Southern Cross Rd, Opp 198 Kohimarama Rd, 255 Kepa Rd, 358 St Heliers Bay Rd Kepa Rd Outside Eastridge, Opp 182 Kepa Rd, 358 St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland Coates Ave Near Nehu -

Submission on Water Issues in Aotearoa New Zealand

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights United Nations Office CH 1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland Submission on Water Issues in Aotearoa New Zealand By Dr Maria Bargh 1 This submission is provided in two Parts: Part One: Overview of the significance of water to Māori and current national legislation relating to water. Part Two: Overview of the potential impacts of the New Zealand government’s proposals on Māori, including with regard to private sector provisions of related services. Introduction In 2003 the New Zealand government established a Sustainable Water Programme of Action to consider how to maintain the quality of New Zealand’s water and its sustainable use. One of the models being proposed for the more efficient management of water is the market mechanism. Dominant theories internationally put forward the market as the best mechanism by which to manage resources efficiently. Given that all life on the planet needs water for survival its appropriate management, use and sustainability is of vital concern. However many communities, including Indigenous peoples, have widely critiqued the market, and the neoliberal policies which promote it, highlighting the responsiveness of the market to money rather than need. In the case of Aotearoa, moves to further utilise the market mechanism in the governance of water raises questions, not simply around the efficiency of the market in this role but also around the Crown i approach which is one of dividing the issues of marketisation, ownership and sustainability in the same manner in which they assume the river/lake beds, banks and water can be divided. -

Comments from Heritage New Zealand

Comment on the Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Fast Track Application 1. Contact Details Please ensure that you have authority to comment on the application on behalf of those named on this form. Organisation name (if relevant) Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga *First name Susan *Last name Andrews Postal address PO Box 105 291, Auckland City 1143 *Home phone / Mobile phone 027 202 3935 *Work phone 09 307 9940 *Email (a valid email address [email protected] enables us to communicate efficiently with you) 2. *We will email you draft conditions of consent for your comment about this application I can receive emails and my email address is I cannot receive emails and my postal address is ✓ correct correct 3. Please provide your comments on the Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Application If you need more space, please attach additional pages. Please include your name, page numbers and Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Application on the additional pages. Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Page 3 of 7 1. Archaeology The archaeological assessment of the subject site prepared by Clough & Associates in 2015, updated in August 2019, appears not to consider the possibility that terraces (which they identify as natural) located within the south western portion of the site may be an extension of archaeological site R11/1196 (terraces with a stone artefact) and that subsurface archaeological remains relating to Maori settlement on the terraces may be present. (See New Zealand Archaeological Authority ArchSite database extract and annotated 1940 aerial below). Kohimarama Comprehensive Care Retirement Village Page 4 of 7 This possible connection was established following a survey of the site completed by Russell Foster in September 2015 for an assessment for the Glen Innes to Tamaki Drive Shared Path1, which resulted in relocation of R11/1196, previously located some 170 metres to the south of the subject property, to a location now only 70 metres south of the subject property. -

New Zealanders' Views on Commemorating Historical

NEW ZEALANDERS’ VIEWS ON COMMEMORATING HISTORICAL EVENTS AUGUST 2 0 1 9 PAGE TABLE OF 1 Background and objectives 3 CONTENTS 2 Research approach 4 3 Summary of key results 6 4 Detailed findings 9 How engaged are New Zealanders in commemorations currently? 9 Why do New Zealanders engage or not? 17 What would encourage deeper engagement in commemorations? 23 Which ways of commemorating appeal most? 30 How relevant and important are different events in our history? 34 Views on the Tuia - Encounters 250 commemoration 38 Views on the annual New Zealand Wars commemorations 44 Views on the annual Waitangi Day commemorations 49 5 Appendix 61 Background and objectives The Ministry for Culture and Heritage wants to The key objective of the research is to discover the factors that know what New Zealanders think about the encourage New Zealanders to engage with commemorative commemoration of historical anniversaries activities or that act as barriers to such engagement The aim is to understand their attitudes towards commemorative activities in order to: - maximise the reach and impact of commemorations, and An additional objective is to establish baseline data for measuring the impact of the Tuia - Encounters 250 commemoration - ensure all New Zealanders experience the social benefits of engagement Colmar Brunton 2019 3 Research approach Colmar Brunton was commissioned to conduct two stages of research Stage 1: A nationally representative survey 2,089 online interviews with New Zealanders aged 15 years or over Stage 2: Two focus groups • One group with young Māori • One group with Asian migrants (a demographic group who are less interested and engaged with commemorations based on the online survey results) Details about each stage can be found in the appendix Colmar Brunton 2019 4 Definition of commemorations Commemorations are a way to officially remember an important event, on a meaningful anniversary. -

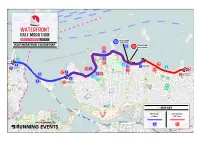

Waterfront-Course-Map-21K.Pdf

de W Auckland Devonport to Rangitoto Island Devonport Wharf Bean Rock Waiheke A uckl a nd - W a ihek e Ferry e Fe Waihek Auckland - Auckland r t ry o Pineharbour Devonpor akapuna Auckland to Coromandel t -T West Bastion Auckland to Coromandel y Reef Auckland to Pineharbour Auckland - Half Moon Bay East Bastion Reef START LINE TAMAKI DRIVE HALF MARATHON COURSE MAP 11 FINISH LINE 12 km SELWYN RESERVE km Orakei Wharf rive i D k 1 a km m Ta 7 Takaparawhau a St an r pi m eet Michael Point Ha Joseph Savage 9 Memorial km Park 7 Selwyn Domain ay 6 Ta Okahu w Tamaki ma le Dr ive Cycleway ki 16 yc Tamaki D Dri Bay e C v temata km mak i Driv e i Ta 20 Judges a Selwyn Av rive Gl 5 W Mar TURNAROUND #2 km a au d C t e s Bay r km escent esce n nue ton Orakei 10 Marau Cr FIRST LAP TURNAROUND #1 Marina km e e Ro FIRST LAP 13 2 t Mission Bay Eltham Road a e Kohimarama 19 e 7 d km km r ve t Avenu 18 ri 17 km S Tagal ad Road Beach i D n k a km Ronaki Road km a n m a so a venue o T A 14 3 e T oad 6 e Cyc am R iv lew T aki Dri km km ay em Rukutai Str ar ve Cyc t y Dr i anaki Road TURNAROUND #4 a Bridge ki Tamaki Patt gate Road a K Road l eet B Dr 8 15 d s 4 m ive tr wa a a e S g T 7 km km Ho o SECOND LAP d nue R e Ju te km ad e v r Road nt lwick T l v o Ku ama S ri aur Watene esce p W u Auckland ee ill Cr A e mar D eet Ni h N C i i a p h g Saint Stephens n o ar t ihil ht Road en Reserve e Str K Hanene e t u C Sage R Cr Ta Ta i Drive re l Cr The a s Long a T e m m it cent s r Titai Str t Reihana Str eet t escent c a a 7 Selwy a e eet Rota Place e ki ki D e