Nurses, Nursing and the Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit SK Films: Facebook/Instagram/Youtube: Amber Hawtin @AmazonAdventureFilm Director, Sales & Marketing Twitter: @SKFilms Phone: 416.367.0440 ext. 3033 Cell: 416.930.5524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amazonadventurefilm.com 1 National Press Release: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMAZON ADVENTURE 3D BRINGS AN EPIC AND INSPIRATIONAL STORY SET IN THE HEART OF THE AMAZON RAINFOREST TO IMAX® SCREENS WITH ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY ON APRIL 18th. April 2017 -- SK Films, an award-winning producer and distributor of natural history entertainment, and HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, the acclaimed film production unit of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, announced today the IMAX/Giant Screen film AMAZON ADVENTURE will launch on April 18, 2017 at the World Premiere event at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The film traces the extraordinary journey of naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates - the most influential scientist you’ve never heard of – who provided “the beautiful proof” to Charles Darwin for his then controversial theory of natural selection, the scientific explanation for the development of life on Earth. As a young man, Bates risked his life for science during his 11-year expedition into the Amazon rainforest. AMAZON ADVENTURE is a compelling detective story of peril, perseverance and, ultimately, success, drawing audiences into the fascinating world of animal mimicry, the astonishing phenomenon where one animal adopts the look of another, gaining an advantage to survive. "The Giant Screen is the ideal format to take audiences to places that they might not normally go and to see amazing creatures they might not normally see,” said Executive Producer Jonathan Barker, CEO of SK Films. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Dominique Moore

14 City Lofts 112-116 Tabernacle Street London EC2A 4LE offi[email protected] +44 (0) 20 7734 6441 DOMINIQUE MOORE Finding Alice (ITV) A Confession (ITV) Four Weddings & A Funeral (Hulu) Television Role Title Production Company Director Producer, Tracey Soph EMILY ATACK SHOW Monkey Kingdom Tommy Forbes Yasmina (Series Regular) FINDING ALICE Bright Pictures / ITV Roger Goldby Steph Walker ANTHONY LA Productions / BBC Terry McDonough Yvette ENTERPRICE Fudge Park / BBC3 Ella Jones Rosie FOUR WEDDINGS & A FUNERAL MGM / Hulu Tristram Shapeero Miss X A CONFESSION ITV Paul Andrew Williams Mrs Connor CREEPED OUT (SEASON 2) Netflix Gareth Tunley Shirley TORVIL & DEAN ITV Gillies Mackinnon Journalist URBAN MYTH: THE TRIAL OF King Bert for Sky Arts Elliot Hegarty JOAN COLLINS Various TRACEY BREAKS THE NEWS BBC Dominic Brigstocke (SERIES 2) Serena MURDER IN SUCCESSVILLE Tiger Aspect James De Fond Rosie QUACKS Lucky Giant Andy De Emmony Various TRACEY BREAKS THE NEWS BBC Dominic Brigstocke (SERIES 1) Chelsea HENRY IX Retort Vadim Jean Various TRACEY ULLMAN’S SHOW BBC Nick Collett Ankita RED DWARF Baby Cow Productions Doug Naylor Yvette OBSESSION DARK DESIRES October Films Jonathan Davenport Cleopatra / Victorian Woman GORY GAMES Lion Television Dominic Brigstocke Various HORRIBLE HISTORIES SPECIALS Lion Television Steve Connelly Annie DRIFTERS (SEASON 2) Bwark Tom Marshall Zara HOLBY CITY BBC Griff Rowland Lottie THE JOB LOT (SEASON 2) Big Talk Productions Luke Snellin Marion THE MIMIC (SEASON 2) Running Bare Productions / Kieron Hawkes Channel 4 Julie POND -

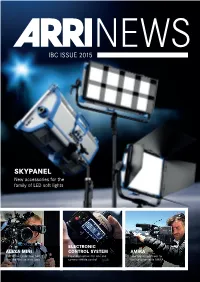

SKYPANEL New Accessories for the Family of LED Soft Lights

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2015 SKYPANEL New accessories for the family of LED soft lights ELECTRONIC ALEXA MINI CONTROL SYSTEM AMIRA Karl Walter Lindenlaub ASC, BVK Expanded options for lens and New application areas for tries the Mini on Nine Lives camera remote control the highly versatile AMIRA EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES We hope you can join postproduction through ARRI Media, illustrating us here at IBC, where we the uniquely broad range of products and services are showcasing our latest we offer. 18 camera systems and lighting technologies. For the ARRI Rental has also been busy supplying the first time in ARRI News we are also introducing our ALEXA 65 system to top DPs on major feature films newest business unit: ARRI Medical. Harnessing – many are testing the large-format camera for the core imaging technology and reliability of selected sequences and then opting to use it on ALEXA, our ARRISCOPE digital surgical microscope main unit throughout production. In April IMAX is already at work in operating theaters, delivering announced that it had chosen ALEXA 65 as the unsurpassed 3D images of surgical procedures. digital platform for 2D IMAX productions. In this issue we share news of how AMIRA is Our new SkyPanel LED soft lights, announced 12 being put to use on productions so diverse and earlier this year and shipping now as promised, are wide-ranging that it has taken even us by surprise. proving extremely popular and at IBC we are The same is true of the ALEXA Mini, which was unveiling a full selection of accessories that will introduced at NAB and has been enthusiastically make them even more flexible. -

Alumni @ Large

Colby Magazine Volume 99 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Article 10 April 2010 Alumni @ Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2010) "Alumni @ Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 99 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol99/iss1/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. ALUMNI AT LARGE 1920s-30s 1943 Meg Bernier Boyd Meg Bernier Boyd Colby College [email protected] Office of Alumni Relations Colby’s Oldest Living Alum: Waterville, ME 04901 1944 Leonette Wishard ’23 Josephine Pitts McAlary 1940 [email protected] Ernest C. Marriner Jr. Christmas did bring some communiqués [email protected] from classmates. Nathan Johnson wrote that his mother, Louise Callahan Johnson, 1941 moved to South San Francisco to an assisted Meg Bernier Boyd living community, where she gets out to the [email protected] senior center frequently and spends the John Hawes Sr., 92, lives near his son’s weekends with him. Her son’s e-mail address family in Sacramento, Calif. He enjoys eating is [email protected]. He is happy to be meals with a fellow World War II veterans her secretary. Y Betty Wood Reed lives and going to happy hour on Fridays. He has in Montpelier, Vt., in assisted living. She encountered some health problems but is is in her fourth year of dialysis and doing plugging along and looking forward to 2010! quite well. -

Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition

The MGB Challenge Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition Peter Bell, Jonathan Kilgour, Steve Renals, Mirjam Wester University of Edinburgh Mark Gales, Pierre Lanchantin, Xunying Liu, Phil Woodland University of Cambridge Thomas Hain, Oscar Saz University of Sheffield Andrew McParland BBC R&D mgb-challenge.org Overview Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Controlled evaluation of speech recognition, speaker diarization, and alignment Using a broad, multi-genre dataset of BBC TV output Subtitles & light supervision • Training data transcribed by subtitles (closed captions) – can differ from verbatim transcripts • edits to enhance clarity • paraphrasing • deletions where the speech is too fast • There may be • words in the subtitles that were not spoken • words missing in the subtitles that were spoken • Additional metadata includes speaker change information, timestamps, genre tags, … MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs • Acoustic model training 1600h broadcast audio across 4 BBC channels (1 April – 20 May 2008), with as-broadcast subtitles – ~33% WER (26% deletions) • Language model -

VETERAN's LIQUORS Zoning for Prof!'Ulonal Offices, As Before Taking Any Action

Page 4 GREENBELT NEWS REVIEW . Thursday, November 14, 1963 P1y lai• for IHI Staff irtenbtlt '< NOW OPEN ••• Vote4 Eff•tive Dec. 1d Phone: GR 4-4881 .,. (bade Wlmllelf7 For your convenience The Greenbelt Hom• IDe. board of cllrectorw voted COI'JICiN'" Open Tues., Wed., Sat. 9 to 8 New Parking Lot In the tiea employees a IOI'ely needed and JoDg a'ftftecl pay mer.. Ill& Thlll'8., Fri. 9 to 9 'l'hunday night The pay hike, which will fatteD ........ ~ rear of Co-op Supenna.rket. .Jltws Btuitw ber 13 pay checb by 8D average ailS tile 1lciMd, perc8at ... CLOSED MONDAYS Space for 120 cars. wu the out,rowth of a nceat 8UrYeY CClllllaet.cl bJ eorpntila management ezpert NatiiUa SbiDdermu. - · , · Volume 27, Number 51 GREENBELT, MARYLAND Permanents $8.50 and Up Thlll'llday, November 21; 1963 Sbfndei'IIWI, wbo bu lhlee be- BONELESS ROUND come a GHI directDr, bad recom- re&IOil for ft. Nllmftl' C.ouncil Handles 2~ Item Agenda, WHAT GOES ON mendecl tbe euti~-Ji¥ lltraGtuN of.. __!_Qefem!4 .ICtlaD ~__L_:ncll!l!t 'lbahctay, N~ !1, 7:SO p.m. the corporation be revamped illont 1DeJ1C1at1on 'to hire AD ............f!w Haryland Deer Hunters Informa linea almilar to that of the Federal a.alltant. Kaaapr Bzube&n cJe.. c tion alnlc, Youth Center government. clared that be · needed GREENBELT BARBER SHOP Approves Zoning FJr Offices a1tbouch lb. Friday, Nowrnber !!, 8 p.m. The increase will brm. GHI wa- help badly, he felt tile pay b-e for 141 Centerway by Charles T. McDcmald Men's Basketball Lea&'Ue a well attended meeting on Monday, November 18, Green gea tc:i a level comparable to that of GHI emplOJM* WU tar more ba Near Post Office and Co-op ~ 8:80, Duplicate Bridge, Hospital· ted portant at thl.l time, and llllld be STEAK eral workers In lfmllar pay could get aJc)q without an aalltant belt C1ty Council ~andled a 22-item agenda and adjourned at 11:15 ity Room grades after they have received the for a wblle. -

Thomas W. L. Cameron

A LASTING LEGACY THOMAS W. L. CAMERON The Chairman of Dividend Assets Capital (DAC), has announced that he will retire from his position at the end of September, but he is emphatic that he has no plans “to sleep through retirement.” Far from it, in fact: Cameron’s morning hours seem to offer him his best ideas… Tom Cameron has arrived at the office early for years – often before seven and often accompanied by his Labrador Retrievers, explained both former business partner Jane Cogswell and Troy Shaver, president and chief executive officer of dac. ith his stack of clipped newspaper and maga- As he did so, Cameron began to create a network of zine articles tucked into his briefcase, Cameron brokerage firms that would meet every two months to dis- has made his morning arrival at dac something cuss their performance. While he attracted new investors, he Wof a ritual. He begins every day in the office by reading three watched companies grow over time, paying particular atten- chapters of the Bible. “He calls it the Owner’s Manual,” Cog- tion to those that increased their dividends at rising rates over swell noted. the same period. “I started getting very excited about the fact After time spent in the Scriptures, Cameron takes out that some of the companies were paying dividends that were his clippings. He does not casually peruse the morning news; growing more than 10% every year,” Cameron explained. he scours three or four newspapers for signposts of market Eager to try out a dividend growth investment strategy, trends and new opportunities. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping as usual that you are all safe and well in these troubled times. Our cinema doors are still well and truly open, I’m pleased to say, the channel has been transmitting 24 hours a day 7 days a week on air with a number of premières for you all and orders have been posted out to you all every day as normal. It’s looking like a difficult few months ahead with lack of advertising on the channel, as you all know it’s the adverts that help us pay for the channel to be transmitted to you all for free and without them it’s very difficult. But we are confident we can get over the next few months. All we ask is that you keep on spreading the word about the channel in any way you can. Our audiences are strong with 4 million viewers per week , but it’s spreading the word that’s going to help us get over this. Can you believe it Talking Pictures TV is FIVE Years Old later this month?! There’s some very interesting selections in this months newsletter. Firstly, a terrific deal on The Humphrey Jennings Collections – one of Britain’s greatest filmmakers. I know lots of you have enjoyed the shorts from the Imperial War Museum archive that we have brought to Talking Pictures and a selection of these can be found on these DVD collections. -

The Quill -- April, 1969 Roger Williams University

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU The Quill Student Publications 4-1969 The Quill -- April, 1969 Roger Williams University Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/the_quill Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Roger Williams University, "The Quill -- April, 1969" (1969). The Quill. Paper 114. http://docs.rwu.edu/the_quill/114 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Quill by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. uf - Without the press . what is speech; without speech . what is freedoni; without freedom • . what is life1 VOL. VIII, No. 10 Roger Williams College April, 1969 New Faculty Appointed Biographical sketches of the !'Gallery, the Providence Art Club MARl'. E . FINGER faculty of the College of Liberal and at the East Greenwich Annual B.A., English, Radcliff College; Arts and Sciences at the Bristol Show. M.A.T., English, Brown Univer Campus are outlined below. The sity. faculty is divided into three broad She taught English at the Uni divisions: Humanities, Social Sci versity of Bridgeport and art for Mrs. Finger has taught at Roger ences, and the Natural Sciences. the Cranston Adult Education and Williams College for the past five the Providence YMCA Adult Edu- years. She will be Coordinator of Areas of study in the Humani cation Programs before joining the Humanities Division at the ties Division include: Art; Eng the Roger Williams faculty two Bristol campus. lish; Foreign Languages; Music; years ago. -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection.