Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commons Mall

RESOLUTION NO.___ BE IT RESOLVED by the Board of Commissioners of the City of Dothan, Alabama, as follows: Section 1. That the City of Dothan enters into an agreement with Wiregrass Commons Mall for the lease of the Community Room as the District 68 polling location for the Special Municipal Election to be held on February 9, 2016 at a cost of $400.00 which said agreement follows: Wiregrass Commons Mall To: Tammy Danner From: Lynne Dickerson, Marketing Director Date: December 10,2015 Re: Required Coverage We will need a Certificate ofInsurance with $1,000,000 Liability Insurance, and the following should be added to the Certificate of Insurance. In Description ofOperations/LocationslVehicles/Special Items should read as follows: Additional Insured's: PR Wiregrass Commons LLC; PREIT Sel'vices, LLC; PREIT Associates, L.P. The Certificate Holder should read as follows: PREIT Associates, L.P. c/o Wiregrass Commons Mall 900 Commons Drive, Suite 414 Dothan, AL 36303 A copy ofthe Certificate of Insurance should be mailed or faxed to our office as soon as possible so we can forward it on to our corporate office. Our address is Wiregrass Commons Mall, 900 Commons Drive STE 414 Dothan, AL 36303. Fax Number: 334~792-0227. Thank you Agreement No: 311580 Partnership Marketing License Agreement This LICENSE AGREEMENT for TEMPORARY SPACE (the "Agreement") is made as of~. by and between the parties identified in Section 1 as "licensor" and "Licensee" upon the tenns and conditions hereinafter set forth. The Standard Terms and Conditions, Licensor's Rules $nd Regulatlons and all Addendums and exhibits attached hereto, if any. -

CONNECTIONS Connectionsdothanarea Chamber of Commerce September2016

CONNECTIONS ConnectionsDothanArea Chamber of Commerce September2016 Celebrating One “GRAND” YEAR PAGE 5 Nate Booth’s Projections AND THE REALITY PAGE 13 Of Today Can your Business AFFORD FSLA Non-Compliance PAGE 14 What’s EventsCalendar September SMTWTFS INSIDE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 September 2016 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 2 Events Calendar 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 3 Ribbon Cuttings 25 26 27 28 29 30 5 Cover Story 6-11 Business Briefs 5 Labor Day – Chamber Closed 12 Grow Dothan 8 Leadership Dothan Class XXXV Reception and Orientation – 5:30 p.m. 13 WorkforceDevelopment Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 14 SmallBusiness Dev elopment 13 Ambassador and Diplomat Committee Meeting – 9 a.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd (Chamber) Also In This Issue Dothan Business Hall of Fame Banquet and Induction Ceremony – 6 p.m. Location: 900 W. Main St. (Wiregrass Church) 6 BFCExpands Social Media *Reservations required: (334) 792-05138 Services 14 Leadership Dothan Class XXXV Opening Retreat – 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. 10 FordFinders Recieves CARF Location: 795 Ross Clark Circle (Wiregrass Rehabilitation Center Inc.) Accreditation Ribbon Cutting: Knockerball Dothan – 10:30 a.m. 11 Trinity Bank Celebrates Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 10 Years Troy University Small Business Counseling – 9:30 a.m. - 1:30 p.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) *Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 15 Leadership Dothan Class XXXV Opening Retreat – 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. Location: 2727 Fortner St. (Harvest Church) Your Cover Photo 19 Youth Leadership Dothan-Houston County Class XXV Application Deadline – 4 p.m. -

CONNECTIONS Connectionsdothan Area Chamber of Commerce July 2019

CONNECTIONS ConnectionsDothan Area Chamber of Commerce July 2019 Meet Tomorrow’s Leaders PAGE 4 Glasstream Celebrates Expansion PAGE 14 Dothan MSA Occupations And Employment PAGE 13 EventsCalendar What’s S M T JulyW T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 INSIDE 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 July 2019 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 2 Events Calendar 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 3 Ribbon Cuttings 28 29 30 31 4-5 Cover Story 7-11 Business Briefs 2 Ambassador and Diplomat Committee Meeting – 9 a.m. 12 Grow Dothan Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 3 LEADS Group 2 Biweekly Meeting – 8 a.m. 13 Workforce Development Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 14 Small Business Development 4-5 Independence Day – Chamber Closed 8 Ribbon Cutting: Southern State Truck Driving School – 10:30 a.m. Also In This Issue Location: 12962 Cottonwood Road 9 Troy University Small Business Counseling – 9:30 a.m. - 1:30 p.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 8 NAPA Sets New World Record *Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 9 King’s Appliances Under New Ribbon Cutting: Something To Talk About – 10:30 a.m. Management Location: 116 E. Slocomb St., Slocomb 10 LEADS Group 1 Biweekly Meeting – 8 a.m. 11 Eagle Eye Announces New Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) Store Manager Ribbon Cutting: Holly Sawyer Law Firm – 10:30 a.m. Location: 294 W. Main St., Suite 103 11 Ribbon Cutting: Encore Rehabilitation, Inc. – 10:30 a.m. Location: 1811 E. Main St., Suite 3 Your Cover Photo 16 Ribbon Cutting: Pearly Gates Funeral Home – 10:30 a.m. -

Chamber Dothan Area Chamber of Commerce December 2020

ConnectionsChamber Dothan Area Chamber of Commerce December 2020 Let’s Keep The Cheer Here Page 4 City, Chamber Host Roundtable Discussion Page 12 Deadline To Apply For PPD Loans Is Dec. 8 Page 16 EventsCalendar December What’s S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 Inside 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 December 2020 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 2 Events Calendar 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 3 Ribbon Cuttings 27 28 29 30 31 4-5 Cover Story 1 Ambassador and Diplomat Committee Meeting – 9 a.m. 7-11 Business Briefs Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) Ribbon Cutting: Chelsea and Joey Photography & Sweet Magnolia Tees – 10:30 a.m. 12 Grow Dothan Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 14 Workforce Development 2 LEADS Group 2 Biweekly Meeting – 8 a.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 16 Small Business Development Ribbon Cutting: Wiregrass Home Team – 10:30 a.m. Location: 2149 Denton Road, Suite 2 DAYP Weekly Eats – 11 a.m. Also In This Issue Location: 3421 Ross Clark Circle (Fazoli’s) 9 Wiregrass Courier Under New Wednesday Webinar: Handling Negative Emotions … Now And In The Future – 2-3 p.m. Location: Zoom Virtual Platform Management *Registration Required. See page 14 for more information. Corresponding Zoom link will be emailed prior to the webinar. 11 Glover Appointed President 3 Leadership Dothan Communication Workshop – 8 a.m. – 5 p.m. Of Alabama Funeral Directors Location: 795 Ross Clark Circle (Wiregrass Rehabilitation Center Inc.’s Sterling Event Services Association Rotary Hall) Ribbon Cutting: Lauren Register Web Design – 10:30 a.m. -

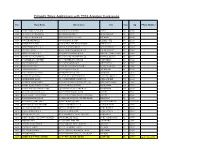

DILLARDS | Annalee Store List

Dillard's Store Addresses with 2018 Annalee Exclusives Store Store Name Address Line 2 City State Zip Phone Number 0141 CARY TOWNE CENTER 1105 WALNUT STREET CARY NC 27511 0143 ALAMANCE CROSSING 1003 BOSTON DRIVE BURLINGTON NC 27215 0146 VALLEY HILLS MALL 1930 US HIGHWAY 70 SE HICKORY NC 28602 0150 SOUTHPARK MALL 4400 SHARON ROAD CHARLOTTE NC 28211 0151 CAROLINA PLACE 11041 CAROLINA PLACE PKWY PINEVILLE NC 28134 0156 INDEPENDENCE MALL 3500 OLEANDER DRIVE WILMINGTON NC 28403 0161 CITADEL MALL 2066 SAM RITTENBERG BLVD. CHARLESTON SC 29407 0162 NORTHWOOD MALL 2150 NORTHWOODS BLVD NORTH CHARLESTON SC 29406 0163 COASTAL GRAND MALL 100 COASTAL GRAND CIRCLE MYRTLE BEACH SC 29577 0164 COLUMBIANA CENTRE 100 COLUMBIANA CIRCLE COLUMBIA SC 29212 0166 HAYWOOD MALL 700 HAYWOOD ROAD GREENVILLE SC 29607 0167 WESTGATE MALL 205 W. BLACKSTOCK ROAD SPARTANBURG SC 29301 0168 ANDERSON MALL 3101 N.MAIN SUITE D ANDERSON SC 29621 0170 MACARTHUR CENTER 200 MONTICELLO AVE NORFOLK VA 23510 0171 LYNNHAVEN MALL 701 LYNNHAVEN PARKWAY VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23452 0172 GREENBRIER MALL 1401 GREENBRIER PARKWAY CHESAPEAKE VA 23320 0174 PATRICK HENRY MALL 12300 JEFFERSON AVENUE STE 300 NEWPORT NEWS VA 23602 0176 SHORT PUMP TOWN CENTER 11824 W BROAD STREET RICHMOND VA 23233 0179 STONY POINT FASHION PARK 9208 STONY POINT PARKWAY RICHMOND VA 23235 0201 INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 2223 N WESTSHORE BLVD TAMPA FL 33607 0203 WESTFIELD CITRUS PARK 8161 CITRUS PARK TOWN CTR MALL TAMPA FL 33625 0204 WESTFIELD BRANDON 303 BRANDON TOWN CENTER MALL BRANDON FL 33511 0205 TYRONE SQUARE MALL 6990 TYRONE SQUARE ST. PETERSBURG FL 337103936 0206 WESTFIELD COUNTRYSIDE 27001 US HIGHWAY 19 N CLEARWATER FL 33761 0207 GULFVIEW SQUARE 9409 U.S. -

CONNECTIONS Connectionsdothan Area Chamber of Commerce January/February 2017

CONNECTIONS ConnectionsDothan Area Chamber of Commerce January/February 2017 NEUROENDOVASCULAR Surgeon Talks With Members PAGE 6 COLEMAN Elected BCA Chairman PAGE 8 MITCHELL Elected To CCAA Board PAGE 11 What’s EventsCalendar February S M T W T F S INSIDE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 January/February 2017 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 2 Events Calendar 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 4-5 Ribbon Cuttings 26 27 28 6 Cover Story 8-14 Business Briefs 1 LEADS Group 2 Meeting – 8 a.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 15 Grow Dothan Military Affairs Committee Meeting and JROTC Awards – 9:30 a.m. 16 Workforce Development Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) LEADS Group 1 Meeting – 11 a.m. 17 Leadership Development Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 18 Small Business Development 2 Ribbon Cutting: Cashwell’s Photo Bar & Portrait Printing – 10:30 a.m. Location: 161 E. Main St. Also In This Issue 7 Ambassador and Diplomat Committee Meeting – 9 a.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 9 Black History Month Events 26th Annual Spotlight On Business Trade Show – 3 - 7 p.m. 12 Hammon Named Employee Location: 126 N. St. Andrews St. (Dothan Civic Center) Ribbon Cutting: Sleep Inn and Suites – 10:30 a.m. Of The Year 9 Location: 4654 Montgomery Highway 13 Home Instead Earns Quality Ribbon Cutting: Tippy Toes Nail Salon – 10:30 a.m. Award 10 Location: 105 Apple Ave., Suite 2 14 Bay Limousine Adds To Fleet Troy University Small Business Counseling – 9:30 a.m. -

Urban Retail Properties, Llc Corporate Overview Table of Contents

CORPORATE OVERVIEW RETAIL PROPERTIES, LLC URBAN RETAIL PROPERTIES, LLC CORPORATE OVERVIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: COMPANY OVERVIEW ....................................................................... 3 Company Information Urban Retail Disciplines Urban Receivership Services Executive Profi les Urban Retail Staff Current Portfolio Urban’s National Scope Client List Historical Perspective Why Choose Urban? SECTION 2: PROFESSIONAL SERVICES ................................................................ 20 Management ....................................................................................................................20 Leasing ...............................................................................................................................23 Specialty Leasing ..............................................................................................................25 Development ....................................................................................................................26 Marketing ...........................................................................................................................33 Market Research/Feasibility Studies ................................................................................36 Tenant Coordination .......................................................................................................37 Environmental and Technical Services ...........................................................................42 Due Diligence ....................................................................................................................46 -

CONNECTIONS Connectionsdothan Area Chamber of Commerce June 2016

CONNECTIONS ConnectionsDothan Area Chamber of Commerce June 2016 AND THE FINALISTS ARE... 2016 Small Business Person PAGE 5 WALLACE OFFERS Speakers Bureau PAGE 7 STRENGTHENING Business Policies PAGE 14 What’s EventsCalendar June S M T W T F S INSIDE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 May 2016 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 2 Events Calendar 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 Ribbon Cuttings 26 27 28 29 30 5 Cover Story 6-11 Business Briefs 1 Ribbon Cutting: Betts Realty – 10:30 a.m. Location: 2323 W. Main St., Suite 102 12 Grow Dothan 2 Ribbon Cutting: Auto Expo – 10:30 a.m. Location: 4083 Ross Clark Circle 13 Workforce Development Leadership Dothan Class 34 Graduation Banquet – 6:30 p.m. 14-15 Small Business Development Location: 126 Museum Ave. (Wiregrass Museum of Art and Conference Center) 7 Ribbon Cutting: Greystone United Methodist Church – 11 a.m. Also In This Issue Location: 4401 Fortner St. 8 Ribbon Cutting: SpectraCare Health Systems Inc.’s Access to Care Program – 8:30 a.m. 8 Praestare Welcomes Location: 3542 Montgomery Highway (Next to Pep Boys) Kearley To Team 9 Small Business Seminar: Social Security As A Cornerstone Of A Sound Retirement Income Plan – 11:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 10 Pickle Promoted To *See page 15 for more information. Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 Market President Dothan Area Young Professionals’ Business Brews – 5:15 p.m. Location: 168 S. Foster St. (RJ Saxons, LLC dba KT’s) 13 Employment Of People Ribbon Cutting: JimPam Hydraulics – 10:30 a.m. -

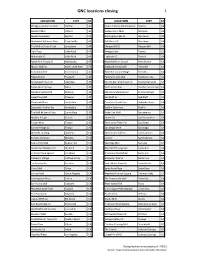

GNC Locations Closing 1

GNC locations closing 1 LOCATION CITY ST LOCATION CITY ST Wiregrass Commons Mall Dothan AL Shops at Dunes On Monterey Marina CA Quintard Mall Oxford AL Vintage Faire Mall Modesto CA Benton Commons Benton AR Huntington Oaks SC Monrovia CA Northwest Arkansas Plaza Fayetteville AR Del Monte SC Monterey CA The Mall at Turtle Creek Jonesboro AR Morgan Hill SC Morgan Hill CA Park Plaza Little Rock AR Vintage Oaks Novato CA Mabelvale SC Little Rock AR Esplande SC Oxnard CA North Park Village SC Monticello AR Westfield Palm Desert Palm Desert CA Mccain Mall SC North Little Rock AR Antelope Valley Mall Palmdale CA Cottonwood SC Cottonwood AZ Town & Country Village Palo Alto CA Flagstaff Mall Flagstaff AZ Panorama City Mall Panorama City CA Arrowhead Town Ctr Glendale AZ Rancho Bernardo Town Ctr Rancho Bernardo CA Superstition Springs Mesa AZ Victoria Gardens Rancho Cucamonga CA Paradise Valley Mall Phoenix AZ Monterey Marketplace Rancho Mirage CA Desert Sky Mall Phoenix AZ Red Bluff SC Red Bluff CA Grayhawk Plaza Scottsdale AZ Galleria at South Bay Redondo Beach CA Scottsdale Fashion Sq Scottsdale AZ Rocklin Commons Rocklin CA The Mall @ Sierra Vista Sierra Vista AZ Arden Fair Mall Sacramento CA Madera Village Tucson AZ Inland Ctr San Bernardino CA Tucson Mall Tucson AZ Tierrasanta Town Ctr San Diego CA Sunrise Village SC Tucson AZ San Diego Mcrd San Diego CA Alameda Landing Alameda CA Stonestown Galleria San Francisco CA Brawley Gateway Brawley CA City Ctr San Francisco CA Buena Park Mall Buena Park CA Eastridge Mall San Jose CA Rancho Marketplace -

CONNECTIONS Connectionsdothan Area Chamber of Commerce August 2016

CONNECTIONS ConnectionsDothan Area Chamber of Commerce August 2016 Outstanding Business LEADERS To Be Inducted PAGE 5 Grow Dothan Team TARGETS Aerospace Connections PAGE 13 What’s EventsCalendar August S M T W T F S INSIDE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 August 2016 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 2 Events Calendar 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 3 Ribbon Cuttings 28 29 30 31 5 Cover Story 7-11 Business Briefs 2 Ambassador and Diplomat Committee Meeting 12 Grow Dothan Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) Small Business Seminar: LinkedIn and You 13 Workforce Development Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber *See page 14 for more information. Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 14 Small Business Development 3 Military Affairs Committee Meeting – 9:30 a.m. Also In This Issue Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 9 Troy University Small Business Counseling – 9:30 a.m. until 1:30 p.m. 9 SpectraCare Receives Honor Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) *Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 11 Cybulsky Joins Flowers Ribbon Cutting: Plato’s Closet – 10:30 a.m. Hospital Administration Location: 2419 Murphy Mill Road 14 New Overtime Rules 11 Small Business Seminar: Video Marketing is the Future Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber Dramatically Increases *See page 14 for more information. Reservations required: (334) 792-5138 Exposure To Employers Dothan Area Young Professionals’ Summer Social – 5:15 p.m. Location: 153 Mary Lou Lane (Folklore Brewing & Meadery) 17 Board of Directors’ Meeting – 8:15 a.m. Location: 102 Jamestown Blvd. (Chamber) 18 Ribbon Cutting: Chick-Fil-A at Wiregrass Commons Mall Your Cover Photo Location: 900 Commons Drive, Suite 407 Your cover photo features two outstanding business 31 General Membership Luncheon – noon CONNECTIONSAugust 2016 ConnectionsDothan Area Chamber of Commerce leaders - Thomas Allen Location: 795 Ross Clark Circle (Wiregrass Rehabilitation Center Inc.’s Sterling Event “Tom” Shirley, Home Oil Services Rotary Hall) Co Inc / Hobo Pantry *Doors and buffet open at 11:30 a.m. -

Summer/Fall 2017 Dixie Daylily

The Dixie Daylily AHS Region 14 Alabama—Mississippi Volume 61, Number 2 Summer / Fall 2017 AHS Region 14 Officers and Liaisons; Club Presidents Regional President Webmaster Alabama Mississippi Terese Goodson Paul Aucoin 7407 Woodley Road 2553 Dunmore Drive Birmingham Daylily Society Hattiesburg Area Daylily Society Montgomery, AL 36116 Hoover, AL 35226 David Allison Vonda C. Martin 334-288-6024 205-824-3592 3525 Laurel View Road 274 City Rd. [email protected] [email protected] Birmingham, AL 35216 Perkinston, MS 39573 205-823-0224 228-861-1646 Regional Publicity Director Youth [email protected] [email protected] Debbie Smith Tricia Folks 10175 Tom Waller Road 289 Ovett-Moselle Rd. Blount Iris and Daylily Society Marion Daylily Society Grand Bay, AL 36541 Moselle, MS 39459 Sandra Little Roger Carr 251-957-0066 601-520-0296 2324 Williams Settlement Road 73 Spell Drive [email protected] [email protected] Blountsville, AL 35031 Columbia, MS 39429 Contact: VP Delois Dunn 601-441-9470 Secretary 205-249-2392 [email protected] Janet Green 1751 S. Williamsburg Rd. Central Alabama Daylily Society Meridian Daylily Club Bassfield, MS 39421 Morris Parr Lois Smith 601-943-5416 4353 South Shades Crest Road 3954 B Pauldin Road [email protected] Bessemer, AL 35022 Meridian, MS 39307 205-602-1273 601-483-1687 Treasurer [email protected] [email protected] Jim Chappell 900 Smokerise Trail Cullman Iris & Daylily Society MS Gulf Coast Daylily Society Warrior, AL 35180 Donnie Douthit Bonnie Lingel 205-647-0688 American 441 County Road 845 P.O. Box 5661 [email protected] Cullman, AL 35057 Vancleave, MS 39565 Hemerocallis Society 256-841-2421 228-826-5596 Editor, The Dixie Daylily petedouthit@yahoo,com [email protected] Oliver Billingslea President 6291 Thach Road Nikki Schmith Mobile Hemerocallis Society North MS/AL Daylily Society Montgomery, AL 36117 424 Pheasant Ct. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re Chapter 11 THE WET SEAL, INC., a Delaware Case No.: 15-10081 (CSS) corporation, et al.1 (Jointly Administered) Debtors. GLOBAL NOTES, METHODOLOGY AND SPECIFIC DISCLOSURES REGARDING THE DEBTORS’ SCHEDULES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES AND STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS Introduction The Wet Seal, Inc., The Wet Seal Retail, Inc., Wet Seal Catalog, Inc., and Wet Seal GC, LLC (collectively, the “Debtors”) with the assistance of their advisors, have filed their respective Schedules of Assets and Liabilities (the “Schedules”) and Statements of Financial Affairs (the “Statements,” and together with the Schedules, the “Schedules and Statements”) with the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware (the “Bankruptcy Court”), pursuant to section 521 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) and Rule 1007 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”). These Global Notes, Methodology, and Specific Disclosures Regarding the Debtors’ Schedules of Assets and Liabilities and Statements of Financial Affairs (the “Global Notes”) pertain to, are incorporated by reference in, and comprise an integral part of each Debtor’s Schedules and Statements. The Global Notes should be referred to, considered, and reviewed in connection with any review of the Schedules and Statements. The Schedules and Statements do not purport to represent financial statements prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in the United States (“GAAP”), nor are they intended to be fully reconciled with the financial statements of each Debtor (whether publically filed or otherwise). Additionally, the Schedules and Statements contain unaudited information that is subject to further review and potential adjustment, and reflect the Debtors’ reasonable efforts to report the assets and liabilities of each Debtor on an unconsolidated basis.