Does School Quality Matter? a Travel Cost Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Board's AP® Computer Science Female Diversity Award

College Board’s AP® Computer Science Female Diversity Award College Board’s AP Computer Science Female Diversity Award recognizes schools that are closing the gender gap and engaging more female students in computer science coursework in AP Computer Science Principles (AP CSP) and AP Computer Science A (AP CSA). Specifically, College Board is honoring schools who reached 50% or higher female representation in either of the two AP computer science courses in 2018, or whose percentage of the female examinees met or exceeded that of the school's female population in 2018. Out of more than 18,000 secondary schools worldwide that offer AP courses, only 685 have achieved this important result. College Board's AP Computer Science Female Diversity Award Award in 2018 School State AP CSA Academy for Software Engineering NY AP CSA Academy of Innovative Technology High School NY AP CSA Academy of Notre Dame MA AP CSA Academy of the Holy Angels NJ AP CSA Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders TX AP CSA Apple Valley High School CA AP CSA Archbishop Edward A. McCarthy High School FL AP CSA Ardsley High School NY AP CSA Arlington Heights High School TX AP CSA Bais Yaakov of Passaic High School NJ AP CSA Bais Yaakov School for Girls MD AP CSA Benjamin N. Cardozo High School NY AP CSA Bishop Guertin High School NH AP CSA Brooklyn Amity School NY AP CSA Bryn Mawr School MD AP CSA Calvin Christian High School CA AP CSA Campbell Hall CA AP CSA Chapin School NY AP CSA Convent of Sacred Heart High School CA AP CSA Convent of the Sacred Heart NY AP CSA Cuthbertson High NC AP CSA Dana Hall School MA AP CSA Daniel Hand High School CT AP CSA Darlington Middle Upper School GA AP CSA Digital Harbor High School 416 MD AP CSA Divine Savior-Holy Angels High School WI AP CSA Dubiski Career High School TX AP CSA DuVal High School MD AP CSA Eastwood Academy TX AP CSA Edsel Ford High School MI AP CSA El Camino High School CA AP CSA F. -

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 December 2018 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname Garland ISD - IA Cable Locate - 2020 Application Number 201001823 Funding Year 2020 Category of Service Category 1 Billed Entity Contact Information GARLAND INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT Russell Neal 720 STADIUM DR GARLAND TX 75040 682-237-7670 972-494-8201 [email protected] [email protected] Billed Entity Number 140461 FCC Registration Number 0001647890 Applicant Type School District Russell Neal / 682-237-7670 Holiday/Summer Contact Information Consulting Firms Name Consultant City State Zip Phone Email Registration Code Number Number VST Services LP 16043688 Trophy Club TX 76262 682-237-7670 [email protected] Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 140461 GARLAND INDEP SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DISTRICT Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 85506 NAAMAN FOREST HIGH Urban 909008 57909008 48 - 20340- None Public School None SCHOOL 6552 Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 85507 COOPER ELEMENTARY Urban 909107 57909107 48 - 20340- None Public School None SCHOOL 2018 85508 VERNAL LISTER Urban 909147 57909147 48 - 20340- None Public School -

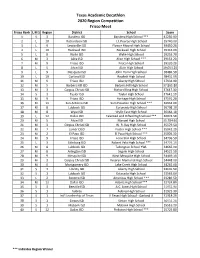

2020 Region Advancing Teams Scores.Xlsx

Texas Academic Decathlon 2020 Region Competition Frisco Meet Frisco Rank L M S Region District School Score 1S3 Bandera ISD Bandera High School *** 41250.90 2L10 Richardson ISD J.J. Pearce High School 39740.00 3L9 Lewisville ISD Flower Mound High School 39450.20 4L10 Rockwall ISD Rockwall High School 39343.00 5L8 Wylie ISD Wylie High School 39255.70 6M3 Alice ISD Alice High School *** 39153.20 7M9 Frisco ISD Frisco High School 39120.20 8L5 Alvin ISD Alvin High School 39,053.20 9L9 Mesquite ISD John Horn High School 38484.50 10 L 10 Garland ISD Rowlett High School 38431.00 11 M 9 Frisco ISD Liberty High School 37934.90 12 M 5 Barbers Hill ISD Barbers Hill High School 37,861.80 13 M 3 Corpus Christi ISD Richard King High School 37647.30 14 S 3 Taylor ISD Taylor High School 37641.10 15 M 9 Frisco ISD Heritage High School 37591.20 16 M 11 San Antonio ISD Sam Houston High School *** 36934.00 17 M 8 Lubbock ISD Coronado High School 36708.10 18 M 8 Wyie ISD Wylie East High School 36164.10 19 L 12 Dallas ISD Talented and Gifted High School *** 36074.50 20 M 5 Alvin ISD Manvel High School 35,784.60 21 M 3 Corpus Christi ISD W. B. Ray High School 35579.50 22 M 7 Lamar CISD Foster High School *** 35042.20 23 M 2El Paso ISD El Paso High School *** 35003.30 24 M 9 Frisco ISD Lone Star High School 34796.50 25 L 3 Edinburg ISD Robert Vela High School *** 34776.10 26 M 8 Lubbock ISD Talkington School YWL 34665.00 27 M 8 Arlington ISD Seguin High School 34525.50 28 M 9 Mesquite ISD West Mesquite High School 34449.10 29 M 3 Corpus Christi ISD Veteran Memorial High School 34448.00 30 M 6 Montgomery ISD Lake Creek High School 34265.00 31 S 3 Liberty ISD Liberty High School 34101.50 32 S 1 Lubbock ISD Estacado High School 33563.60 33 L 2 Socorro ISD Americas High School *** 33289.50 34 M 12 Dallas ISD Adams High School *** 32724.80 35 S 3 Beeville ISD A.C. -

Employee Handbook 2021-2022 Published by Department of Human Resources Garland Independent School District

Garland Independent School District Serving the North Texas Communities of Garland, Rowlett, and Sachse Employee Handbook 2021-2022 Published by Department of Human Resources Garland Independent School District If you have difficulty accessing the information in this document because of a disability, please email/call Dr. Kishawna Wiggins: [email protected] or 972-487-3057 Si necesita que le preparen una traducción de este documento, favor de comunicarse con Dr. Kishawna Wiggins: [email protected] or 972-487-3057 Nếu quí vị cần tài liệu này được dịch, vui lòng email/gọi: Dr. Kishawna Wiggins: [email protected] or 972-487-3057 Garland Independent School District in support of school districts and Career and Technical Education Programs, does not discriminate on the basis of sex, disability, race, color, age or national origin in its educational programs, activities, or employment as required by Title IX, Section 504 and Title VI. Table of Contents Employee Handbook Receipt/Acknowledgement ...................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 District Map Page 1 .................................................................................................................. 8 District Map Page 2 .................................................................................................................. 9 Mission Statement, Goals, and Objectives ........................................................................ -

City of Rowlett City Council Agenda

CITY OF ROWLETT CITY COUNCIL AGENDA Our Vision: A well-planned lakeside community of quality neighborhoods, distinctive amenities, diverse employment, and cultural charm. Rowlett: THE place to live, work and play. Tuesday, May 21, 2019 5:30 P.M. Municipal Building As authorized by Section 551.071 of the Texas Government Code, this meeting may be convened into closed Executive Session for the purpose of seeking confidential legal advice from the City Attorney on any agenda item herein. The City of Rowlett reserves the right to reconvene, recess or realign the Regular Session or called Executive Session or order of business at any time prior to adjournment. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. EXECUTIVE SESSION There are no items for this agenda. 3. WORK SESSION (5:30 P.M.)* Times listed are approximate. 3A. Joint Work Session of Golf Advisory Board and City Council. (45 minutes) 3B. Discuss an amendment to Chapter 77-704 of the Rowlett Development Code (RDC) to include Article 211.006(f) of the Texas Local Government Code, providing that the affirmative vote of at least three-fourths of City Council be required to overrule a recommendation of denial by the Planning and Zoning Commission. (20 minutes) 3C. Discuss a proposed ordinance to adopt the 2019 Water Conservation Plan and the 2019 Water Resource and Emergency Management Plan (jointly the Water Management Plan) as required by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). (15 minutes) 3D. Update on dockless bike systems in the City. (20 minutes) 4. DISCUSS CONSENT AGENDA ITEMS CONVENE INTO THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS (7:30 P.M.)* INVOCATION PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TEXAS PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Honor the Texas Flag; I pledge allegiance to thee, Texas, one state under God, one and indivisible. -

Improvement Plan

Garland Independent School District Rowlett High School 2018-2019 Campus Improvement Plan Rowlett High School Campus #009 1 of 29 Generated by Plan4Learning.com August 12, 2018 5:46 pm Mission Statement We will support academic and social excellence in a global society for diverse students through the combined efforts of all community members. Vision We will prepare individual students for their best future by collaborating together and demonstrating excellence, every day. Value Statement We believe all students can learn, every day. We will work together to promote and achieve high expectations, every day. We know that students deserve our best, every day. We value all cultures, every day. We respect all students, families, staff and community members, every day. We demonstrate ethical behavior, every day. We will hold each other accountable for our actions, every day. We believe education transforms lives, every day. Rowlett High School Campus #009 2 of 29 Generated by Plan4Learning.com August 12, 2018 5:46 pm Table of Contents Comprehensive Needs Assessment . 4 Student Achievement . 4 School Culture and Climate . 6 Comprehensive Needs Assessment Data Documentation . 8 Goals . 9 Goal 1: Garland ISD will ensure ALL students graduate prepared for college, careers and life by increasing student performance measures, postsecondary readiness, and graduation rates and decreasing student management incidences. 9 System Safeguard Strategies . 26 Site-Based Decision Making Committee . 27 2018-2019 Campus Improvement Team . 28 Campus Funding Summary . 29 Rowlett High School Campus #009 3 of 29 Generated by Plan4Learning.com August 12, 2018 5:46 pm Comprehensive Needs Assessment Student Achievement Student Achievement Strengths Qualifying scores on all AP exams increased from 35.6% in 2017 to 41.3% in 2018. -

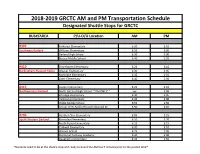

2018-2019 GRCTC AM and PM Transportation Schedule Designated Shuttle Stops for GRCTC

2018-2019 GRCTC AM and PM Transportation Schedule Designated Shuttle Stops for GRCTC BUS#/AREA P/U-D/O Location AM PM #307 Parkcrest Elementary 6:20 3:10 Southwest Garland Williams Elementary 6:25 3:05 Garland High School 6:30 3:00 Bussey Middle School 6:40 2:55 #410 Shorehaven Elementary 6:25 3:10 Buckingham-Pleasant Valley Weaver Elementary 6:30 3:05 Northlake Elementary 6:35 2:55 Lister Elementary 6:40 2:50 #415 Cooper Elementary 6:25 3:10 Northwestern Garland North Garland High School **PM ONLY** xxx 3:06 Ethridge Elementary 6:30 3:05 Hickman Elementary 6:35 3:00 Webb Middle School 6:55 2:50 Corner of W Apollo Rd and Idlewood Dr 6:50 2:45 #706 Heather Glen Elementary 6:05 3:25 South Western Garland Montclair Elementary 6:10 3:20 Routh Roach Elementary 6:15 3:15 Caldwell Elementary 6:20 3:10 Warren School 6:25 3:05 Memorial Pathway Academy 6:30 3:00 Daugherty Elementary 6:35 2:55 *Students need to be at the shuttle stop and ready to board the AM bus 5 minutes prior to the posted time* #716 Pearson Elementary 6:05 3:30 Western Rowlett and Herfurth Elementary 6:10 3:35 Herfurth-Pearson Corner of Harborview Bd and Gulfport Dr 6:15 3:25 Corner of Chaha Rd and Kirby Rd 6:21 3:20 Coyle Middle School 6:26 3:10 Rowlett Elementary 6:31 3:15 Dorsey Elementary 6:38 3:00 Back Elementary 6:43 2:55 #718 Walnut Glen Academy 6:25 3:10 West Garland Bullock Elementary 6:30 3:05 Bradfield Elementary 6:35 3:00 Jackson MST 6:40 2:55 #720 Corner of Hunters Glen Dr and Whitley Rd 6:05 2:55 Northeastern Rowlett Corner of County Line Rd and Trewitt Ln 6:10 -

Stars Notes Science Teacher Access to Resources at Ut Southwestern

STARS NOTES SCIENCE TEACHER ACCESS TO RESOURCES AT SOUTHWESTERN STARS Notes 2017 STARS Summer Research Program for Teachers September 2017 Issue XV, Number 3 Our 2017 SRP was a huge success! See what the teachers had to say: “Aromatase Deletion in Adipose Tissue in Mice” Tennile Betz Thompson Middle School Hosted by: Orhan K. Oz, M.D., Ph.D. Radioloy “I have had an unforgettable summer learning a new set of skills that I can take back to the classroom. It has been an eye opening experience learning what takes place in a research lab; and the processes involved in doing scientific research. I would also like to thank Dr. Orhan K. Oz and the Department of Radiology for opening up their lab and allowing summer interns to take part in their research.” “Comparison of Theta Oscillations Recorded from the Anterior and Posterior Hippocampus of Epileptic Patients” Constance Bond Naaman Forest High School Hosted by: WHAT’S Bradley Lega, M.D. Neurology INSIDE SRP Teachers……. .1 SRP Students……..3 Summer Camps…..4 Upcoming Events..5 “The STARS Program has allowed me to explore my passion for science on a deeper Staff & Programs…6 level by gaining hands on laboratory research. This, in turn, makes me excited to return to my classroom and share my experience and new-found knowledge with my incoming students. I believe this is an important and beneficial program that all science teachers of all grade levels should participate in- you won’t regret it!” 1 2017 STARS Summer Research Program cont. “Activation Mechanisms in Protein Kinases” Rochelle Grant Robert T. -

Brain Awareness Week Partner List

Brain Awareness Week Partner List Brain Awareness Week is the global campaign to foster public enthusiasm and support for brain science. Every March, partners host imaginative activities in their communities that share the wonders of the brain and the impact brain science has on our everyday lives. Partners include colleges and universities, hospitals, medical research institutions, K-12 schools, advocacy groups, outreach organizations, professional associations, government agencies, corporations, and more. Since its founding in 1996, Brain Awareness Week has included the participation of more than 8,200 partners in 124 countries. The map above shows the geographical distribution of Brain Awareness Partners worldwide. Click on a country in the list below to be brought to that section in the Partner List. Georgia Kuwait Norway Spain Albania Chile China Germany Latvia Pakistan Sri Lanka Algeria Hong Kong (China) Ghana Lebanon Palestine Sudan Argentina Macau (China) Greece Lesotho Panama Sweden Armenia Colombia Grenada Liberia Paraguay Switzerland Australia Costa Rica Guatemala Libya Peru Taiwan Austria Côte d’Ivoire Guyana Lithuania Philippines Tanzania Bahamas Croatia Haiti Luxembourg Poland Thailand Bahrain Cuba Hungary Madagascar Portugal Trinidad and Tobago Bangladesh Cyprus Iceland Malaysia Qatar Tunisia Belgium Czech Republic India Malta Romania Turkey Belize Democratic Republic Indonesia Mexico Russia Uganda Benin of the Congo Iran Moldova Saudi Arabia Ukraine Bolivia Denmark Iraq Mongolia Senegal United Arab Emirates Bosnia and -

Tornado Strikes Near Carrollton Public School

\K( \hi \( ,1 1 FRIDAY Sbptembbi 7,2001 Vol. 87 No. 13 Todayi IS B ® Htfi91Low75 SEP 1 2 2 / f Htfi 87 Low 76 An independent newspaper serving Southern Methodist University • Dallas, Texas smudailycampus.com Tornado strikes near Carrollton public school By De'Borah Bankston SENIOR STAFF WRITER • BANKSTONI0UREACH.COM TcfffifXiSft* MYTHS ; Just 17 miles northwest of the SMU cam pus lies McCoy Elementary School in There are many misconceptions iCarrollton. that swirl around tales of torna ' Wednesday, this school was witness to •the first recorded tornado strike in the city's dos. Knowing the truth about • history. this phenomenon can pro tea you ; School was in session and the day was in the event of a storm. •coming to an end as winds blasted through ;the neighborhood. The storm snapped power and telephone • Tornadoes are not always clearly ilines, damaged homes, and ripped apart :trees across the Dallas suburb. visible, they are often hidden by At Polk Middle School, children fol heavy rainfall. lowed standard tornado safety procedures and no one was injured. • Damage caused by tornados ; "We didn't try to downplay the serious doesn't stem from changes in air • ness of this with the children, but we were pressure, but from the dangerous ;calm. This carried over to everyone," said ;Mark Hyatt, Assistant Superintendent of ly fast winds of the storm. Thus, Support Services for the Carrollton-Farmers opening windows will not protect Branch Independent School District. "Everyone went into the halls, just like we your house - in fact, it could do for the drills and there were no prob make it more vulnerable. -

High School Cheerleader Deduction System

Table of Contents I. PHILOSOPHY/PURPOSE X. REPLACEMENTS II. OBJECTIVES XI. MAINTAINING ELIGIBILITY A. Eligibility ConCerning CreDits III. DEFINITION 1. Conditions 2. Regaining Eligibility IV. TRYOUT ELIGIBILITY 3. Summer School A. Enrolment B. Eligibility ConCerning Grades B. ACademiC Grades 1. Academic Requirements C. ConDuCt 2. Academic Suspension V. COMMITMENT XII. GENERAL CONDUCT A. Statement ConCerning ConDuCt VI. FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY B. Statement ConCerning SoCial MeDia C. Discipline VII. COST COVERED BY THE GISD 1. Suspension 2. Expulsion/Alternative Education Center VIII. STUDENT COST 3. Drugs, Alcohol, Tabaco and Illegal Activity 4. Removal/Resignment IX. SELECTION A. Basis XIII. RECOMMENDATIONS & GUIDELINES FOR B. LoCation CHEERLEADING SAFETY C. Tryouts 1. Packets XIV. CHEERING ACTIVITIES 2. Procedures A. Football D. Squad Makeup 1. All Squads E. Judging Criteria 2. Varsity Cheerleaders 1. Scoring Breakdown 3. Junior Varsity Cheerleaders 2. Minimum Scores 4. Freshman Cheerleaders F. Judges B. Volleyball 1. Number C. Basketball 2. Minority Judges D. Other ACtivities 3. Certification 4. Statement of Acquaintance XV. SOCIAL ACTIVITIES/BOOSTER CLUBS 5. Basis 6. In District Judges XVI. COMPETITION SQUADS G. Panel Tryouts H. SCore Tabulation XVII. INCLIMENT WEATHER 1. Entry 2. Score Calculation XVIII. TRANSPORTATION 3. Minimum Requirements 4. Score Retention XIX. BOOSTER CLUBS 5. Statement of Finality 6. Ties XX. MONIES COLLECTED BY SPONSORS I. For Varsity CanDiDates Only 1. JV Deficiency 2. Stipulations AppenDix 1 – StuDent Cost Estimate J. ExCeptions AppenDix 2 – GISD CentralizeD Tryouts 1. Ties AppenDix 3 – GISD Cheer JuDging Criteria 2. Injury AppenDix 4 – Jump/Tumbling SCoring Criteria 3. Video Usage Guidelines AppenDix 5 – Stipulations For Placing Varsity CanDiDates K. -

Garland ISD 501 S

All education is NOT equal. are you choosing the best? Entrant: Tiffany Veno Director of Communications Garland ISD 501 S. Jupiter Road Garland, TX 75042 972-487-3258 [email protected] garlandisd.net Type of School/Organization Submitting Entry: School District: Over 25,000 Entry Category: Marketing/BrandingCampaigns Please consider this entry for a Golden Achievement Award! #choosegarlandisd All Education Is Not Equal. Are You Choosing The Best? #ChooseGarlandISD With school choice a contested issue across the United States, Garland ISD wants to ensure that every family living in the district makes an informed decision. GISD not only offers true choice by allowing families to attend any school in the district—whether it’s down the street or across town—but it also boasts 17 selective magnet campuses, access to six different world language options, a free associate degree, over 200 career-training programs, transportation, comprehensive special education services, a 100 percent highly qualified teaching staff, and more. No other educational entity in the cities of Garland, Rowlett and Sachse can claim this expansive list of options. However, GISD has seen a steady decline in enrollment for the past five years. This comes at a time when the Texas Legislature continues to decrease funding for public schools and competition from popular charter and private schools continues to increase. Looking ahead to the future, the district knew it must become the area’s No. 1 choice, which meant reaching beyond just sharing good news to begin selling the district itself. During the 2017-18 school year, Garland ISD Communications launched its #ChooseGarlandISD campaign with a goal of informing students, staff, parents, businesses and the community about everything the district offers and what sets it apart from other educational options.