Michael Robert Heintze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950

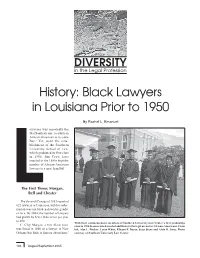

DIVERSITY in the Legal Profession History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950 By Rachel L. Emanuel ouisiana was reportedly the first Southern state to admit an African-American to its state Bar.1 Yet, until the esta- blishment of the Southern University School of Law, which graduated its first class in 1950, Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s kept the number of African-American lawyers to a mere handful. The First Three: Morgan, LBell and Chester The Seventh Census of 1853 reported 622 lawyers in Louisiana, but this infor- mation was not broken down by gender or race. By 1864, the number of lawyers had grown by fewer than seven per year to 698. With their commencement, members of Southern University Law Center’s first graduating C. Clay Morgan, a free black man, class in 1950 became much-needed additions to the legal arena for African-Americans. From was listed in 1860 as a lawyer in New left, Alex L. Pitcher, Leroy White, Ellyson F. Dyson, Jesse Stone and Alvin B. Jones. Photo Orleans but little is known about him.2 courtesy of Southern University Law Center. 104 August/September 2005 There were only four states reported to have admitted black lawyers to the bar prior to that time, none of them in the South. The states included Indiana (1860s), Maine (1844), Massachusetts (1845), New York (1848) and Ohio (1854). If, as is believed, Morgan was Louisiana’s first black lawyer,3 he would have been admitted to the Bar almost 10 years earlier than the average date for the other Southern states (Arkansas, 1866; Tennessee, 1868; Florida and Missis- sippi, 1869; Alabama, Georgia, Ken- tucky, South Carolina and Virginia, 1871; and Texas, 1873). -

Dillard University, Which Has Its Roots in Reconstruction, Has Outlasted Segregation, Discrimination and Hurricane Katrina

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Dillard 1718 ~ 2018 University was chartered on 300 June 6, 1930. TRICENTENNIAL THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION PHOTOS THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A group portrait of graduating nurses in front of Flint-Goodrich Hospital of Dillard University in 1932 Straight University in 1908, on Canal and Tonti streets Class President Nicole Tinson takes a selfie with then frst lady Michelle Obama during Dillard’s 2014 graduation. Dillard President Walter M.Kimbrough stands behind Obama. THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION New Orleans University in 1908, on St. Charles Avenue, was razed to make way for De La Salle High School. Dillard University, which has its roots in Reconstruction, has outlasted segregation, discrimination and Hurricane Katrina. THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE The university was created in 1930 from the opposition of the neighborhood. The first two historically black colleges — Straight president of the university, Will W. Alexander, University and Union Normal School — later was a white man because there were concerns named New Orleans University. that a white faculty wouldn’t want to answer The two schools were both created in 1868 to a black president. When Dillard opened its to educate newly freed African-Americans. new campus in 1935, it featured prominent fac- The schools offered professional training, in- ulty including Horace Mann Bond in psychol- The library of the new cluding in law, medicine and nursing. New ogy and education; Frederick Douglass Hall in Dillard University in 1935 Orleans University opened the Flint-Go- music; Lawrence D. -

Lincoln Site Interpreter Training Workshop Presented by the NATIONAL PARK SERVICE and the ORGANIZATION of AMERICAN HISTORIANS

National Park Service National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site; Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial; Lincoln Home National Historic Site Lincoln Site Interpreter Training Workshop Presented by the NATIONAL PARK SERVICE and the ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS Hosted by ABRAHAM LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Hodgenville, Kentucky May 22- 23, 2007 LINCOLN HOME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Springfield, Illinois June 4- 5, 2007 LINCOLN BOYHOOD NATIONAL MEMORIAL Lincoln City, Indiana June 7- 8, 2007 www.nps.gov EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA 2007 National Park Service National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site; Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial; Lincoln Home National Historic Site Lincoln Site Interpreter Training Workshop Agenda-Day 1 8:30 a.m. Welcome/Introductions 8:40 a.m. Interpreting Lincoln Within the Context of the Civil War - MT-M & DTP Challenges of talking about Lincoln and slavery at historic sites Centennial and South Carolina (1961) Lincoln Statue in Richmond (2003) Ft. Sumter Brochure - before and after Appomattox Handbook - before and after 10:00 Break 10:15 – Slavery and the Coming of the War - MT-M Origins and expansion of slavery in the British North American colonies Slavery in the United States Constitution Slavery’s Southern expansion and Northern extinction, 1790- 1820 Failed compromises and fatal clashes: the frontier as the focus in the struggle over slavery, 1820- 1860 The rise and fall of political parties 12:00 Lunch 1:30 – Lincoln and the Republican Party in the Context of the 1850s - MT-M Public opinion in the first era of courting public opinion The popular culture of political rallies, newspapers, novels, religious tracts, and oratory Rise of abolitionism and pro- slavery factions Their arguments – emotional, "scientific," political, moral. -

Regional Concerns During the Age of Imperialism. Marshall E

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1995 The outhS and American Foreign Policy, 1894-1904: Regional Concerns During the Age of Imperialism. Marshall E. Schott Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Schott, Marshall E., "The outhS and American Foreign Policy, 1894-1904: Regional Concerns During the Age of Imperialism." (1995). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6134. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6134 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master.UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

2005-2007 Undergraduate Catalog

TSU TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY 3100 Cleburne Street Houston, Texas 77004 (713) 313-7011 www.tsu.edu TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY 1 GUIDE TO COURSE OFFERINGS PREFIX ACADEMIC DISCIPLINE PAGE PREFIX ACADEMIC DISCIPLINE PAGE ACCT Accounting (56) MUSA Applied Music (168) AD Art and Design (211) MUSI Music (168) AJ Administration of Justice (265) PA Public Affairs (256) ART Art (168) PADM Pharmacy Administration (286) AWS Airway Science (398) PAS Pharmaceutical Applied Sciences (280) BADM Business Administration (66) PE Human Performance (113) BIOL Biology (326) PHAR Pharmacy (280,286) CFDV Child and Family Development (211) PHCH Pharmaceutical Chemistry (280) CHEM Chemistry (338) PHIL Philosophy (228) CIVT Civil Engineering Technology (355) PHYS Physics (391) CM Communication (134) POLS Political Science (256) COE Cooperative Education (355,370,398) PSY Psychology (228) CONS Construction Technology (370) RDG Reading Education (81) CS Computer Science (347) SC Speech Communication (134) CT Clothing and Textiles (211) SOC Sociology (242) DRFT Drafting and Design Technology (370) SOCW Social Work (234) ECON Economics (194) SPAN Spanish (154) EDCI Curriculum and Instruction (81) SPED Special Education (81) ELET Electronics Engineering Technology (370) TC Telecommunications (134) ENG English (154) THC Theatre (168) ENGT Engineering Technology (335) FIN Finance (56) FN Foods and Nutrition (211) FR French (154) GEOG Geography (194) HED Health (113) HIST History (194) HSCR Health Sciences Core (295) HSCS Human Services and Consumer Sciences (211) HSEH Environmental Health (211) HSHA Health Administration (295) HSMR Health Information Management (295) HSMT Medical Technology (295) HSRT Respiratory Therapy (295) INS Insurance (56) ITEC Industrial Technology (370) JOUR Journalism (134) MATH Mathematics (383) MFG Automated Manufacturing Technology (370) MGMT Management (66) MGSC Management Science (66) MKTG Marketing (66) MSCI Military Science (265) *Designations in parentheses refer to page numbers in this document where courses offered under the prefixes specified are referenced. -

2003-2005 Undergraduate Catalog

TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY 3100 Cleburne Avenue Houston, Texas 77004 (713) 313-7011 www.tsu.edu TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY 1 Guide to Course Offerings SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ACCTG Accounting MGMT Management BADM Business Administration MGSC Management Science FIN Finance MKTG Marketing INS Insurance COLLEGE OF EDUCATION COUN Counseling EPSY Educational Psychology EDAS Educational Administration HED Health EDCI Curriculum and Instruction PE Human Performance EDFD Educational Foundation RDG Reading EDHI Higher Education SPED Special Education COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES ART Art JOUR Journalism CFDEV Child and Family Development MUSAP Applied Music CM Communication MUSI Music CT Clothing and Textile PHIL Philosophy ECON Economics PSY Psychology ENG English SC Speech Communication FN Foods and Nutrition SOC Sociology FR French SOCW Social Work GEOG Geography SPAN Spanish GEOL Geology TC Telecommunications HIST History THC Theatre HSCS Human Services and Consumer Sciences COLLEGE OF PHARMACY AND HEALTH SCIENCES HSCR Health Sciences Core HSRT Respiratory Therapy HSEH Environmental Health PADM Pharmacy Administration HSHA Health Administration PAS Pharmacy, Allied Sciences HSMR Health Information Management PHARM Pharmacy HSMT Medical Technology PHCH Pharmaceutical Chemistry SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS AJ Administration of Justice PAD Public Administration MSCI Military Science PLN City Planning PA Public Affairs POLSC Political Science COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AWS Airway Science ELET Electronics Engineering Technology BIOL -

THE CONNERS of WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS in TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A

THE CONNERS OF WACO: BLACK PROFESSIONALS IN TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXAS by VIRGINIA LEE SPURLIN, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved ~r·rp~(n oj the Committee li =:::::.., } ,}\ )\ •\ rJ <. I ) Accepted May, 1991 lAd ioi r2 1^^/ hJo 3? Cs-^.S- Copyright Virginia Lee Spurlin, 1991 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is a dream turned into a reality because of the goodness and generosity of the people who aided me in its completion. I am especially grateful to the sister of Jeffie Conner, Vera Malone, and her daughter, Vivienne Mayes, for donating the Conner papers to Baylor University. Kent Keeth, Ellen Brown, William Ming, and Virginia Ming helped me immensely at the Texas Collection at Baylor. I appreciated the assistance given me by Jene Wright at the Waco Public Library. Rowena Keatts, the librarian at Paul Quinn College, deserves my plaudits for having the foresight to preserve copies of the Waco Messenger, a valuable took for historical research about blacks in Waco and McLennan County. The staff members of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Texas State Library in Austin along with those at the Prairie View A and M University Library gave me aid, information, and guidance for which I thank them. Kathy Haigood and Fran Thompson expended time in locating records of the McLennan County School District for me. I certainly appreciated their efforts. Much appreciation also goes to Robert H. demons, the county school superintendent. -

PUB DATE Atademic Computing at Jackson. State University. A

2. '4 DOCUMENT RESUME . " .7 ED 210. 023 IR 009 829, .1" II 9 ., AUTHOR Hunter; Beverly- . TITLE Atademic Computing atJackson.State University. A , case Study. i INSTITUTION .. Huldan Ilesburces Research Organization, Alexandria, _-; , . Va. ....../ SPONSAGENCY, Rational ScienceFoundation, WaSlingtom, D.0 . 'Minority InstittAions ,Science Improvement program.." ., . PUB DATE 80 , k-. GRANT' SER-1914601 :60pm; For related document, see ED 208 931. NOTE , EDRS.PRICE' M*01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Colleges; *Computer Oriented Programs; Computer Programs; *Cciputer Science Education; Higher Education f Input Output Devicei; Liberal Arts; *Minority Gioups: Organization; Outcomes of Education; Outreach .Programs; Prbfiles IDENTIFIERS *Computer Centers; Computer Literacy; *Jackson State University MS ,N. ', , . -- o -, ASSTR ACT .° : .'inepared:63, the Human Re'gourCes Researcr--- ation , to assist aldministrators4 faculty,Staft.i-andS-inAem-s elk other minotit/Linstitutipase't6 plan, extend, or improve uses of computers, this case Study is one 1-4-series sn educational applicaticns of computers..4A profi-e ofJatkson State UniversiWid,mtifies the location; programs, mi'ssiOnr-nuibers of faculty 'and students,tuition -and tinancial.aid, acpreditation,- Andthe budget, and a chronology of significant events leiding,te the present.state ofacademic' computing is. provided,. An .explanation of the ftngtional organizAtion and' 'uanagement of the central academic cOmpilfing and support,including organization charts, is followeebyt1) discussions of poli ies, hardware, software, and courses which faCilitate students' se of computers;(2) course's and;reguirdients foc both undergradua and . pro-gram; .01-7-a listo . graduate ffitudents,in the computer scieif kwpartaents requiring majprvto take compuker scienceCb.urses;(4) a- dlOcriptionof theleadership tole of Jackson State Univeisity in regionalv?. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

PREVIEW First Section 2

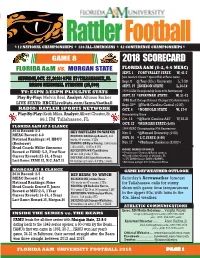

FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY / RATTLERS / FOOTBALL Rattler Football * 12 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS * 130 ALL-AMERICANS * 42 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS * GAME 8 2018 SCORECARD FLORIDA A&M vs. MORGAN STATE FLORIDA A&M (5-2, 4-0 MEAC) SEPT. 1 FORT VALLEY STATE W, 41-7 SATURDAY, OCT. 27, 2018 / 4 PM ET / TALLAHASSEE, FL Jake Gaither Classic * Sports Hall of Fame Game Sept. 8 @ Troy (Ala.) University L, 7-59 BRAGG MEMORIAL STADIUM (25,500) SEPT. 15 JACKSON STATE L,16-18 TV: ESPN 3/ESPN PLUS/LIVE STATS 1978 NCAA Championship Team 40th Anniversary Play-By-Play: Melvin Beal. Analyst: Alfonso Barber SEPT. 22 *SAVANNAH STATE W, 31-13 1998 Black College National Champs 20th Anniversary LIVE STATS: HBCULiveStats.com/famu/football Sept. 29 * @North Carolina Central (4:00) RADIO: RATLER SPORTS NETWORK OCT. 6 *NORFOLK STATE W, 17-0 Play-By-Play: Keith Miles. Analyst: Albert Chester, Sr. Homecoming Game 96.1 FM Tallahassee, FL Oct. 13 *@North Carolina A&T W, 22-21 OCT. 27 *MORGAN STATE (4:00) FLORIDA A&M AT A GLANCE 1988 MEAC Championship 30th Anniversary 2018 Record: 5-2 KEY RATTLERS TO WATCH Nov. 3 *@Howard University (1:00) MEAC Record: 4-0 RUSHING: RB Bishop Bonnett, 343 NOV. 10 * S.C.STATE (4:00) National Rankings: #1 HBCU yards, 43 carries, 3 TDs (Boxtorow) PASSING: QB Ryan Stanley, 1,545 yards, Nov. 17 *#Bethune-Cookman (2:00)% Head Coach: Willie Simmons (122 of 202), 10 TDs, 6 INT RECEIVING: WR Chad Hunter HOME GAMES IN BOLD Record at FAMU: 5-2, First Year *Conference Games; @Away games; 32 rec, 446 yards, 5 TDs Career Record: 27-13, 4 Years #Florida Blue Classic at Orlando, FL DEFENSE: LB Elijah Richardson, %-TV ESPNClassic/ESPN3/ESPNU; Last Game: FAMU 22, N.C. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vita ROSETTA E. ROSS, Ph.D. Spelman College 350 Spelman Lane, SW Atlanta, GA 30314 (404) 270-5527/270-5523 (fax) Education 1995 Ph.D., Religion (Religious Ethics), concentration in Christian Ethics with a focus on religion and Civil Rights activism, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. 1989 M.Div., Candler School of Theology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. 1979 M.A., English (American Literature), with a focus on the fiction of American author Joseph Heller, Howard University, Washington, District of Columbia. 1975 B.A., English, The College of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina Teaching Posts 2003-present Professor of Religion, Spelman College. Associate Professor of Religion, Spelman College (2003-2011). 1999-2003 McVay Associate Professor of Ethics, United Theological Seminary. 1994-1999 Assistant Professor of Ethics, Interdenominational Theological Center. Other Experience 2008-2009 Interim Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Howard University Divinity School. Spring, 2006 Visiting Scholar, Africa University, Mutare, Zimbabwe. Fall, 2002 Exchange Faculty, Hamline University, St. Paul, Minnesota. 1996-1997 Acting Director, Black Church Studies, Candler School of Theology, Emory University. Scholarly Foci Disciplinary Studies: Religious Studies, Christian Ethics. Sub-disciplinary Topics: Ethics and Social Justice The Civil Rights Movement; Religion and Black Women’s Activism; Womanist Religious Thought; Black Women Civil Rights Activists. Black Religions and Identity Religion and African American Identity; Continental and Diasporan African Women’s Religious Identities and Engagement. Religious Studies The Academic Study of Religions; Theory and Methods in Religious Studies. Research and Publications Books and Monographs Academic African American Women in the NAACP: Religion, Social Advocacy, and Self-Regard, in preparation. Black Women and Religious Cultures, New Journal Founder and Editor, first issue, Volume 1, Issue 1, November 2020, hosted by Manifold at the University of Minnesota Press. -

African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship

Catholic University Law Review Volume 43 Issue 1 Fall 1993 Article 4 1993 Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship Dena S. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Dena S. Davis, Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship, 43 Cath. U. L. Rev. 109 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC ENCOUNTER: AFRICAN-AMERICANS, AMERICAN JEWS, AND THE CHURCH- STATE RELATIONSHIP Dena S. Davis* I. INTRODUCTION This Essay examines a paradox in contemporary American society. Jewish voters are overwhelmingly liberal and much more likely than non- Jewish white voters to support an African-American candidate., Jewish voters also staunchly support the greatest possible separation of church * Assistant Professor, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. For critical readings of earlier drafts of this Essay, the author is indebted to Erwin Chemerinsky, Stephen W. Gard, Roger D. Hatch, Stephan Landsman, and Peter Paris. For assistance with resources, the author obtained invaluable help from Michelle Ainish at the Blaustein Library of the American Jewish Committee, Joyce Baugh, Steven Cohen, Roger D. Hatch, and especially her research assistant, Christopher Janezic. This work was supported by a grant from the Cleveland-Marshall Fund. 1. In the 1982 California gubernatorial election, Jewish voters gave the African- American candidate, Tom Bradley, 75% of their vote; Jews were second only to African- Americans in their support for Bradley, exceeding even Hispanics, while the majority of the white vote went for the white Republican candidate, George Deukmejian.