John Gauden, First Biographer of Richard Hooker: an Influential Failure*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Hooker

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 2,or. - Qºbe (5teat Qbutchmen 56tíč3 EDITED by VERNON STALEY RICHARD HOOKER ** - - - ---- -- ---- - -- ---- ---_ RICHARD HOOKER. Picture from National Portrait Gallery, by perm 13.5 to ºr 0. 'f Macmillan & Co. [Frontispiece. ICHARD as at HOOKER at By VERNON STALEY PROVOST OF THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH of ST. ANDREW, INVERNESS ... • * * * LONDON: MASTERS & CO., LTD. 1907 78, NEW BOND STREET, w. \\ \ \ EDITOR'S PREFACE It has been recently said by one accustomed to weigh his words, “I do not think it can be doubted that in the early years of Queen Elizabeth a large part, numerically the larger part, of the clergy and laity who made up the Church of England was really Catholic at heart, though the Reformers made up for deficiency of numbers by energy and force of conviction.” And again, “When Elizabeth came to the throne, the nation was divided between a majority of more or less lukewarm Catholics no longer to be called Roman, and a minority of ardent Protestants, who were rapidly gaining—though they had not quite gained—the upper hand. The Protestantism generally was of a type current in South West Germany and Switzerland, but the influence of Calvin was increasing every day.” Dr. Sanday here uses the term “Catholics,” in the * Dr. Sanday, Minutes of Evidence taken before The Royal Com †: on Ecclesiastical Discipline, 1906. Vol. III. p. 20, §§ 16350, V b 340844 vi EDITOR'S PREFACE sense of those who were attached to the old faith and worship minus certain exaggerations, but who disliked the Roman interference in England. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates

HANDBOUND AT THE UNIVERSITY OF YALE STUDIES IN ENGLISH ALBERT S. COOK, EDITOR. XL THE TENURE OF KINGS AND MAGISTRATES BY JOHN MILTON EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY WILLIAM TALBOT ALLISON, B.D., PnD., PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, WESLEY COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA, WINNIPEG A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 191 1 WEIMAR: PRINTED BY R. WAGNER SOHN. PREFACE It is not a little surprising, when one considers the amount of attention that has been bestowed on Milton's poetry, that his prose tracts, with a very few excep- tions, have lain so neglected in recent times. The present edition is an attempt to remedy this neglect, so far as one of these treatises is concerned. Others, it is will follow and hoped, ; indeed, The Ready Easy Way to establish a Free Commonwealth has already been taken in hand. A portion of the expense of printing this book has been borne by the Modern Language Club of Yale University, from funds placed at its disposal by the generosity of Mr. George E. Dimock, of Elizabeth, New Jersey, a graduate of Yale in the Class of 1874. ALBERT S. COOK. YALE UNIVERSITY, January, 1911. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i I. DATE AND AUTHORSHIP .... i II. HISTORICAL SITUATION vi xii III. PURPOSE . .... xiv IV. LEADING IDEAS .... xix V. THE COVENANT . ... VI. THE PRESBYTERIAN DIVINES xxiii VII. USE OF SCRIPTURE . xxvi VIII. BACKGROUND OF POLITICAL THOUGHT . xxx xxxviii IX. SOURCES ... ' X. STYLE . * . xlvi XI. -

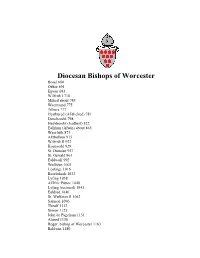

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title -

Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond Proceedings of the conference held at St Francis Theological College, Milton, February 12-14 2010 Edited by Marcus Harmes Lindsay Henderson & Gillian Colclough © Contributors 2010 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First Published 2010 Augustine to Anglicanism Conference www.anglicans-in-australia-and-beyond.org National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harmes, Marcus, 1981 - Colclough, Gillian. Henderson, Lindsay J. (editors) From Augustine to Anglicanism: the Anglican Church in Australia and beyond: proceedings of the conference. ISBN 978-0-646-52811-3 Subjects: 1. Anglican Church of Australia—Identity 2. Anglicans—Religious identity—Australia 3. Anglicans—Australia—History I. Title 283.94 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print http://www.csdigitalprint.com.au/ Acknowledgements We thank all of the speakers at the Augustine to Anglicanism Conference for their contributions to this volume of essays distinguished by academic originality and scholarly vibrancy. We are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided to us by all at St Francis’ Theological College, the Public Memory Research Centre at the University of Southern Queensland, and Sirromet Wines. Thanks are similarly due to our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland: librarians Vivienne Armati and Alison Hunter provided welcome assistance with the cataloguing data for this volume, while Catherine Dewhirst, Phillip Gearing and Eleanor Kiernan gave freely of their wise counsel and practical support. -

1 Hagiography and Theology for A

Hagiography and Theology for a Comprehensive Reformed Church: John Gauden and the portrayal of Ralph Brownrigg The Rev’d Dr Stephen Hampton Dean Peterhouse Cambridge CB2 1RD United Kingdom 1 Hagiography and Theology for a Comprehensive Reformed Church: John Gauden and the portrayal of Ralph Brownrigg I) The life and death of Ralph Brownrigg Ralph Brownrigg1 died in his lodgings in the Temple in London on 7 December, 1659. He was buried at the Temple Church ten days later. John Gauden preached the funeral sermon, and later remarked on the quality of his audience. Brownrigg’s eminence was demonstrated, he suggested, By that honourable and ample concourse of so many eagles to his corpse and funerals, which were attended by noblemen, by gentlemen, by judges, by lawyers, by divines, by merchants and citizens of the best sort then in London; these flocked to his sepulchre, these followed the bier, these recounted his worth, these deplored their own and their age’s loss of him.2 Thomas Fuller, who also attended the service, lamented the loss of Brownrigg’s salutary influence upon the life of the Church. In his History of the Worthies of England, which was published a couple of years later, he wrote: I know all accidents are minuted and momented by divine providence; and yet I hope I may say without sin, his was an untimely death, not to himself (prepared thereunto) but as to his longer life; which the prayers of pious people requested, the need of the Church required, the date of nature could have permitted, but the pleasure of God (to which all must submit) denied. -

Journal of Academic Perspectives

Journal of Academic Perspectives Early Modern History of Theology: Richard Hooker, Elizabethan Puritanism and Predestination Andrea Hugill, Graduate Student, Toronto School of Theology, Canada ABSTRACT The first part of the paper seeks to place Richard Hooker in context by examining the public debates with reformers, especially the Puritan Thomas Cartwright. Cartwright's theology is examined in some measure of detail because his position was the one Hooker responded to directly both in his major work, Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Polity, in which he cites from Cartwright's writing and also in the incomplete manuscript now held in Trinity College, Dublin, that he wrote at the end of his life in response to A Christian Letter and as a defence against Cartwright's accusations, entitled Dublin Fragments, which addresses the subject of predestination, especially with reference to the Anglican articles of religion that Cartwright had accused him of contradicting. Hooker's defence of the Church of England is said to have been a reaction to Cartwrightian Puritanism. Furthermore, Hooker disclosed the deficiencies of the Puritan understanding of revelation and introduced a strong humanist element in early modern theological thought. The second part of the paper outlines Hooker's views on grace and predestination, and the third part concludes the paper arguing the main point of the paper, that Hooker's views on grace and predestination are consistent with other Reformation figures, despite public debates. Hooker's first public appearance created controversy on different opinions about the topic of predestination and together with his views expressed addressing those who urged reformation in the Church of England in Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Polity, led to the criticism published in the second last year of his life in A Christian Letter. -

Richard Hooker and His Theory of Anglicanism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1959 Richard Hooker and His Theory of Anglicanism Marilyn Jean Becic Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Becic, Marilyn Jean, "Richard Hooker and His Theory of Anglicanism" (1959). Master's Theses. 1540. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1540 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1959 Marilyn Jean Becic by Marilyn Jean Beeic A 7hesls Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola Cn1vers1ty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements tor the Degree of 14aster of .Arts June 1959 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTROroCTION • .. .. • • • • • • • • • • 1 Protestant Reformation--Engllsh reform--Eocle!l sstteel Poltty--Rlehard Hooker--Character- Contemporary oplnion--Blrth--Famlly--Patrons- Oxford--Degrees--Hebrew Instruotor--Expulsion trom Corpus ChrlstI--Relnstatement--Ordination- St. Paults Cross--Puritan movement--Puritan ten ete--Booker's marriage--Recent scholarship--Mas tership ot the Temple--Walter Travers--Controversy --CalvInist threat--Eocleslastlos1 Pollty--Its Purpose--Its oontent--John Ohurchman--First four booka--Edwin Sandys, Jr.--Copyright--Fifth book- Sixth and eIghth books--Ohuroh livings--Absentee Ism--Blshopabourne--Death--WI1l--Authentlolty of Polltz--Theorles--Supportlng authentloIty--Re ]eoting authentlcIty--Early AnglIcan system--Iook erts oontributions. -

Alt Context 1861-1896

1861 – Context – 168 Agnes Martin; or, the fall of Cardinal Wolsey. / Martin, Agnes.-- 8o..-- London, Oxford [printed], [1861]. Held by: British Library The Agriculture of Berkshire. / Clutterbuck, James Charles.-- pp. 44. ; 8o..-- London; Slatter & Rose: Oxford : Weale; Bell & Daldy, 1861. Held by: British Library Analysis of the history of England, (from William Ist to Henry VIIth,) with references to Hallam, Guizot, Gibbon, Blackstone, &c., and a series of questions / Fitz-Wygram, Loftus, S.C.L.-- Second ed.-- 12mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland An Answer to F. Temple's Essay on "the Education of the World." By a Working Man. / Temple, Frederick, Successively Bishop of Exeter and of London, and Archbishop of Canterbury.-- 12o..-- Oxford, 1861. Held by: British Library Answer to Professor Stanley's strictures / Pusey, E. B. (Edward Bouverie), 1800-1882.-- 6 p ; 22 cm.-- [Oxford] : [s.n.], [1861] Notes: Caption title.-- Signed: E.B. Pusey Held by: Oxford Are Brutes immortal? An enquiry, conducted mainly by the light of nature into Bishop Butler's hypotheses and concessions on the subject, as given in part 1. chap. 1. of his "Analogy of Religion." / Boyce, John Cox ; Butler, Joseph, successively Bishop of Bristol and of Durham.-- pp. 70. ; 8o..-- Oxford; Thomas Turner: Boroughbridge : J. H. & J. Parker, 1861. Held by: British Library Aristophanous Ippes. The Knights of Aristophanes / with short English notes [by D.W. Turner] for the use of schools.-- 56, 58 p ; 16mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland Arnold Prize Essay, 1861. The Christians in Rome during the first three centuries.