Journal of Academic Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Hooker

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 2,or. - Qºbe (5teat Qbutchmen 56tíč3 EDITED by VERNON STALEY RICHARD HOOKER ** - - - ---- -- ---- - -- ---- ---_ RICHARD HOOKER. Picture from National Portrait Gallery, by perm 13.5 to ºr 0. 'f Macmillan & Co. [Frontispiece. ICHARD as at HOOKER at By VERNON STALEY PROVOST OF THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH of ST. ANDREW, INVERNESS ... • * * * LONDON: MASTERS & CO., LTD. 1907 78, NEW BOND STREET, w. \\ \ \ EDITOR'S PREFACE It has been recently said by one accustomed to weigh his words, “I do not think it can be doubted that in the early years of Queen Elizabeth a large part, numerically the larger part, of the clergy and laity who made up the Church of England was really Catholic at heart, though the Reformers made up for deficiency of numbers by energy and force of conviction.” And again, “When Elizabeth came to the throne, the nation was divided between a majority of more or less lukewarm Catholics no longer to be called Roman, and a minority of ardent Protestants, who were rapidly gaining—though they had not quite gained—the upper hand. The Protestantism generally was of a type current in South West Germany and Switzerland, but the influence of Calvin was increasing every day.” Dr. Sanday here uses the term “Catholics,” in the * Dr. Sanday, Minutes of Evidence taken before The Royal Com †: on Ecclesiastical Discipline, 1906. Vol. III. p. 20, §§ 16350, V b 340844 vi EDITOR'S PREFACE sense of those who were attached to the old faith and worship minus certain exaggerations, but who disliked the Roman interference in England. -

Provosts Template

TAble oF ConTenTs Table of illustrations ix Foreword xi Preface xv Acknowledgements xix ChAPTer 1 Adam loftus 1 ChAPTer 2 Walter Travers 15 ChAPTer 3 henry Alvey 28 ChAPTer 4 William Temple 32 ChAPTer 5 William bedell 41 ChAPTer 6 robert ussher 61 ChAPTer 7 William Chappell 67 ChAPTer 8 richard Washington 76 ChAPTer 9 Faithful Teate 78 ChAPTer 10 Anthony Martin 82 ChAPTer 11 samuel Winter 86 ChAPTer 12 Thomas seele 101 ChAPTer 1 3 Michael Ward 108 ChAPTer 14 narcissus Marsh 112 ChAPTer 15 robert huntington 127 ChAPTer 16 st george Ashe 140 ChAPTer 17 george browne 148 ChAPTer 18 Peter browne 152 ChAPTer 19 benjamin Pratt 159 ChAPTer 20 richard baldwin 168 ChAPTer 21 Francis Andrews 185 ChAPTer 22 John hely-hutchinson 198 ChAPTer 2 3 richard Murray 217 ChAPTer 24 John Kearney 225 ChAPTer 25 george hall 229 ChAPTer 26 Thomas elrington 236 ChAPTer 27 samuel Kyle 247 ChAPTer 28 bartholomew lloyd 259 ChAPTer 29 Franc sadleir 275 ChAPTer 30 richard MacDonnell 290 ChAPTer 31 humphrey lloyd 309 ChAPTer 32 John hewitt Jellett 324 ChAPTer 33 george salmon 334 ChAPTer 34 Anthony Traill 371 ChAPTer 35 John Pentland Mahaffy 404 ChAPTer 36 John henry bernard 450 references 493 bibliography PublisheD WorKs 535 books 535 edited books 542 sections of books 543 Journals and Periodicals 544 Dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference Works 549 Pamphlets and short Works 550 histories of the College 550 newspapers 551 other Works 551 unPublisheD WorKs 553 index 555 viii TAble oF illusTrATions The illustrations are portraits, unless otherwise described. With the exception of the portrait of bedell, all the portraits of the Provosts are reproduced from those in the collection of the College by kind permission of the board of Trinity College Dublin. -

History and the Shaping of Irish Protestantism

Journal of the Irish Christian Study Centre Vol. 2 1984 History and the Shaping of Irish Protestantism (Based on the Annual Theological Lectures delivered at the Queen's University of Belfast, 21st and 22nd February, 1983) by DESMOND BOWEN 'History has mauled Ireland, but if we can prove ourselves able to learn from it, we may once again find ourselves in a position to teach'. James Downey, Them and Us: Britain, Ireland and the Northern Question, 1969-1982, (Dublin, 1983) The History In a world filled with insurgent ethnic groups the importance of the role of 'peoples' in world development is being increasingly recognized in our day, and Arnold Toynbee has gone so far as to argue "it is the only intelligible unit of historical study" .1 The Protestants of Ireland have until now formed a people unit with a strong sense of identity based on a configuration of political and religious symbols by which they explain their history. The social orders in both north and south which have long nurtured them are changing rapidly, however, and as a people they are now suffering from what in modern jargon is called 'an identity crisis'. They are confused with their self-image, the understanding of themselves historically, and their relationship with other peoples, which has traditionally given them their identity. This paper addresses itself to this crisis, suggesting that a new consideration of Irish Protestant historical development might be of value to them in both self-understanding, and in terms of what they might contribute to the world as a consequence of their unique historical experience. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

Chapter IV – the English and Irish Reformation. England. in 1521

Chapter IV – The English and Irish Reformation. England. In 1521 the English monarch forwarded to Rome a copy of the treatise he had just completed in refutation of “Martin Luther the heresiarch”:* On this occasion, Clerk, the envoy** who presented the sumptuous manuscript to Leo X, expatiated on the perfect orthodoxy of his countrymen and their entire devotion to the Roman pontiff; – little dreaming that in the course of the next thirty years an era fatal to the old opinions would have dawned on every shire of England as on other parts of Western Christendom, and least of all anticipating that one of the prime movers in the changes then accomplished would be Henry VIII himself, who in return for his chivalrous vindication of the schoolmen had been dubbed “Defender of the Faith.”*** *[Above: cf. Audin’s narrative in his Hist. de Henri VIII. I. 259 sq. Paris, 1847. The zeal of the monarch was inflamed and his arguments supported by the leading prelates of the day. Thus Fisher bp. of Rochester preached at St Paul’s (May 12, 1521) “again ye pernicious doctryn of Martin Luther”; his sermon professing to have been “made by assyngnement of ye moost reuerend fader in God ye lord Thomas cardinal of York” [i.e. Wolsey]. Two years later appeared the same prelate’s more elaborate defense of Henry VIII entitled Adsertionis Lutheranae Confutatio, and also Powel’s Propugnaculum, the title of which characterizes Luther as an infamous friar and a notorious “Wicklifist”. On subsequent passages between the two chief antagonists, Henry VIII and Luther, see Waddington, II. -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Richard Hooker and Episcopal Ecclesiology in the Church of England SHIPP, ELIZABETH,ANN How to cite: SHIPP, ELIZABETH,ANN (2021) Richard Hooker and Episcopal Ecclesiology in the Church of England, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13940/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 RICHARD HOOKER AND EPISCOPAL ECCLESIOLOGY IN THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND BY ELIZABETH ANN SHIPP SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY AND RELIGION 2020 Abstract This thesis argues that in the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Polity, Richard Hooker presented a coherent and skilful defence of the 1559 Settlement as being congruent with wider Protestantism. It then explores how Hooker’s theory of episcopal ecclesiology as presented in the Lawes has influenced the contemporary episcopal polity of the Church of England. -

Final Copy 2019 01 23 Wilkin

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Wilkins, Vernon Title: A Field the Lord hath Blessed the Person, Works, Life and Polemical Ecclesiology of Richard Field, DD, 15611616 General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. “A Field the Lord hath Blessed” The Person, Works, Life and Polemical Ecclesiology of -

The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates

HANDBOUND AT THE UNIVERSITY OF YALE STUDIES IN ENGLISH ALBERT S. COOK, EDITOR. XL THE TENURE OF KINGS AND MAGISTRATES BY JOHN MILTON EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY WILLIAM TALBOT ALLISON, B.D., PnD., PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, WESLEY COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA, WINNIPEG A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 191 1 WEIMAR: PRINTED BY R. WAGNER SOHN. PREFACE It is not a little surprising, when one considers the amount of attention that has been bestowed on Milton's poetry, that his prose tracts, with a very few excep- tions, have lain so neglected in recent times. The present edition is an attempt to remedy this neglect, so far as one of these treatises is concerned. Others, it is will follow and hoped, ; indeed, The Ready Easy Way to establish a Free Commonwealth has already been taken in hand. A portion of the expense of printing this book has been borne by the Modern Language Club of Yale University, from funds placed at its disposal by the generosity of Mr. George E. Dimock, of Elizabeth, New Jersey, a graduate of Yale in the Class of 1874. ALBERT S. COOK. YALE UNIVERSITY, January, 1911. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i I. DATE AND AUTHORSHIP .... i II. HISTORICAL SITUATION vi xii III. PURPOSE . .... xiv IV. LEADING IDEAS .... xix V. THE COVENANT . ... VI. THE PRESBYTERIAN DIVINES xxiii VII. USE OF SCRIPTURE . xxvi VIII. BACKGROUND OF POLITICAL THOUGHT . xxx xxxviii IX. SOURCES ... ' X. STYLE . * . xlvi XI. -

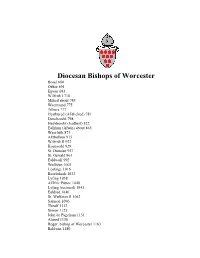

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title