How Old Is a Tune?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fiddle Traditions the Violin Comes to Norway It Is Believed That The

The fiddle traditions The violin comes to Norway It is believed that the violin came to that violins from this period were Norway in the middle of the 1600s brought home by, amongst others, from Italy and Germany. This was Norwegian soldiers who fought in probably as a result of upper class wars in Europe. music activities in the towns. But, much suggests that fiddle playing was known in the countryside before this. Already around 1600 ‘farmer fiddles’ are described in old sources, and named fiddlers are also often encountered. We know of the Hardanger fiddle from the middle of the 1600s, which implies that a fiddle-making industry was already established in the countryside before the violin was popular in the Norwegian towns. Rural craftsmen in Norway must have acquired knowledge about this new instrument from 1500s Italy and been inspired by it. One can imagine From 1650 onwards, the violin quickly became a popular instrument throughout the whole of the country. We have clear evidence of this in many areas – from Finnmark, the rural areas of the West Coast and from inland mountain and valley districts. The fiddle, as it was also called, was the pop instrument of its day. There exist early descriptions as to how the farming folk amused themselves and danced to fiddle music. In the course of the 1700s, its popularity only increased, and the fiddle was above all used at weddings and festive occasions. Fiddlers were also prominent at the big markets, and here it was possible to find both fiddles and fiddle strings for sale. -

Excitement Grows with the Sigdalslag Decision to Join with Four Other

Excitement grows with the Sigdalslag decision to join with four other bygdelags, Hadeland, Land, Telernark and Toten, in sharing a portion of the time June 29-30 and in separate sessions which are of special purpose and interest to each lag when all gather on the St. Olaf College campus, Northfield, Minnesota. Velkommen! Each lag will use advance registration and payment of fees. You may wish to complete this form today when you have read this newsletter. No tickets will be available for the bapquet buffet except by advance sale. A visitor badge will be issued for those able to attend only a portion of the day to include a user fee at $ 3..00 each day. All lags have the same registration fee. Highlights of the weekend will include the evening programs Friday and Saturday to which the public is invited. Dr. Harland Foss,. President of St. Olaf College will bring greetings and Dr. Sidney Rand, former ambassador to Norway and a past-president at St. Olaf, together with his wife Lois will present "Nilkkenog Nissen" in Sigdal and Hadeland Friday evening. Music and singing and coffee offer opportunities to participate. Saturday afternoon and evening the Gjevre VII family will provide instrumental music. Five children and their parents perform and share a Norwegian-American heritage that lS lively, informative entertainment. Folk dancers known as among the most acclaimed in Norway present the after-the- banquet program Saturday evening. The Sogn-Fjordane Ringen in bunads of various districts of Norway's west coast performs regional Cbygedans) dances such as vestlands springar, gamalt, rudl, halling, pols; pattern dances such as reels, row dances, couple dances-- all turdans forms; popular gammaldans or old-fashioned waltz, reinlender, schottische, mazurka and polka dances for couples; and finally the songdans which derive from the Middle Ages and are kept alive in the Faeroe Islands in the tradition of the epic lays. -

TOCN0004DIGIBKLT.Pdf

NORTHERN DANCES: FOLK MUSIC FROM SCANDINAVIA AND ESTONIA Gunnar Idenstam You are now entering our world of epic folk music from around the Baltic Sea, played on a large church organ and the nyckelharpa, the keyed Swedish fiddle, in a recording made in tribute to the new organ in the Domkirke (Cathedral) in Kristiansand in Norway. The organ was constructed in 2013 by the German company Klais, which has created an impressive and colourful instrument with a large palette of different sounds, from the most delicate and poetic to the most majestic and festive – a palette that adds space, character, volume and atmosphere to the original folk tunes. The nyckelharpa, a traditional folk instrument, has its origins in the sixteenth century, and its fragile, Baroque-like sound is happily embraced by the delicate solo stops – for example, the ‘woodwind’, or the bells, of the organ – or it can be carried, like an eagle flying over a majestic landscape, with deep forests and high mountains, by a powerful northern wind. The realm of folk dance is a fascinating soundscape of irregular pulse, ostinato- like melodic figures and improvised sections. The melodic and rhythmic variations they show are equally rich, both in the musical tradition itself and in the traditions of the hundreds of different types of dances that make it up. We have chosen folk tunes that are, in a more profound sense, majestic, epic, sacred, elegant, wild, delightful or meditative. The arrangements are not written down, but are more or less improvised, according to these characters. Gunnar Idenstam/Erik Rydvall 1 Northern Dances This is music created in the moment, introducing the mighty bells of the organ. -

SUMMER 2009 K R a M E L E T - T S E W Welcome to Kviteseid Med Morgedal Og Vrådal

WEST-TELEMARK S U M M E R 2 0 0 9 Welcome to Kviteseid med Morgedal og Vrådal Activities, adventure, culture and tradition Kviteseid, Morgedal, Vrådal – an exciting part of Telemark • KVITESEIDBYEN Kilen Feriesenter (campsite) Kviteseidbyen is an idyllic village by Beautifully situated by lake Flåvatn, the Telemark Canal. It is a lively and about 30 km from Kviteseid village. pleasant commercial and local Cabins for rent. Beach, water slide, government centre, with some forty boats for rent, fast food restaurant. companies involved in most lines of tel. +47 35 05 65 87 www.kilen.as business. The canal boat Victoria visits the harbour during the summer. The FOOD AND BEVERAGES harbour is also open to tourist boats, Waldenstrøm Bakeri (bakery shop) and is free of charge. Washing machi - tel. +47 35 05 31 59 ne, toilets, shower facilities and septic Bryggjekafeen (cafeteria on the wharf) tanks are available. The tourist office tel. +47 95 45 15 46 on the wharf is a WiFi hotspot. Straand Restaurant www.kviteseidbyen.no tel. +47 35 06 90 90 ATTRACTIONS TOURIST INFORMATION Kviteseid Folk Museum Kviteseid Tourist Information and Kviteseid old church Kviteseid bryggje (the wharf) Outdoor museum with 12 old buil - tel. +47 95 45 15 46 dings. Kviteseid old church is a Romanesque stone church, dating TAXI from the 12th century. Opening hours: Kviteseid taxi, tel. +47 94 15 36 50 11:00-17:00, every day 13 Jun- 16 Aug • MORGEDAL – the cradle of modern tel. +47 35 07 73 31/35 05 37 60 skiing. A visit to Morgedal will take you www.vest-telemark.museum.no straight into the history of skiing, from the days of the pioneers to modern times. -

Fra Presidenten

Volume 22 Number 3 Fall 2017 Published 3 times per year by: Nord Hedmark og Hedemarken Lag 2018 Tre-Lag Stevne August 8-11, 2018 Fra Presidenten, Notice, it’s one-week Fall is my favorite time of year. It is later than usual. partly the changing season with cool temperatures and beautiful colors, but my Austin Convention Center enjoyment is mostly tied to the many At the Holiday Inn Hotel traditional activities that begin in the fall. Yard work may be a 1498 4th St. N., necessity, but how we each go about dealing with our bulbs, leaves and general preparation for winter is part of our own Austin MN 55912 traditions. How we celebrate Halloween, and Thanksgiving are Theme - “Norway Evolving” part of our traditions. Do you always have candied yams, or pumpkin pie, or green bean casserole with your turkey? We In the next newsletter, we will have always have lefse, which I’m certain they didn’t have at the first information to make reservations. Thanksgiving. But we are Norwegian, so we will be thankful with There are two hotels involved. a Scandinavian twist. More information in the March, 2018 issue. This weekend the family got together for our annual lefse baking party. Check out the news and This year we only made 112, but that was information from enough to divide 7 ways and still provide Fellesraad Bygdelag enough for the family Christmas dinner, too. on the web site to help After Thanksgiving there will be krumkake Norway House to grow. and sandbakkels made, along with many other traditional holiday treats. -

Fra Halling Til Reinlender

Institutt for musikkvitenskap, UiO Litteratur MUS1301 V2010 1 Fra halling til reinlender Historisk skisse av runddansens / gammaldansens inntog i norske danse- og instrumentaltradisjoner. Av Olav Sæta Ved midten av 1800-tallet hadde fela og hardingfela vært dominerende som folkelige instrumenter til dans og seremonier i hver sine omr˚aderi Norge i rundt et ˚arhundre. Fele hadde riktignok vært i bruk siden 1600- tallet, der et 30-talls dokumenterte tilfeller antyder felebruk godt spredt over landet, bortsett fra i visse samiske omr˚ader.Og fra første del av 1700- tallet framtrer et bilde av felas generelt stigende posisjon og popularitet. Rundt hardingfelas opphav og alder fins enkelte uklare momenter, men en framvekst i Hardanger virker sikker. Tida for omfattende utbredelse av slike feler til betydelige omr˚aderi Sør-Norge { Vestlandet fra nordre Rogaland til Sogn, Telemark, Numedal, Hallingdal og Valdres { var fra 1750-60-tall og framover noen ti˚ar(se art. om feletradisjoner). I ettertid er disse omr˚adene{ som ble noe utvidet etter hvert { p˚afolkemusikkspr˚ak kalt hardingfeleomr˚ader.Øvrige distrikter i landet er kalt feleomr˚ader, eller omr˚aderfor vanlig fele. Fra denne perioden og til godt inn p˚a1800-tallet virker bruken av de to feletypene i hovedsak ˚aha vært svært parallell. Eldre skikker og praksis for musikkbruk i samværsformer og seremonier virker ˚aha vært temmelig ensartet landet over i det gamle bondesamfunnet, som omfattet rundt 90% av befolkningen. Bruken av felemusikk gjaldt først og fremst til tidas aktuelle sl˚atterepertoar knyttet til dansens brede plass i samværsformene og til marsjer i bryllups- seremoniene. Slik inngikk denne musikken i, og var dels formet av, sosiale funksjoner { ved sida av ˚agi musikalsk opplevelse. -

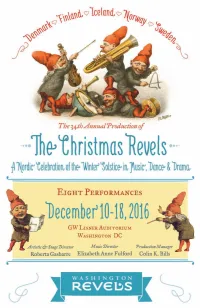

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

Norway – Music and Musical Life

Norway2BOOK.book Page 273 Thursday, August 21, 2008 11:35 PM Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life By Arvid Vollsnes Through all the centuries of documented Norwegian music it has been obvi- ous that there were strong connections to European cultural life. But from the 14th to the 19th century Norway was considered by other Europeans to be remote and belonging to the backwaters of Europe. Some daring travel- ers came in the Romantic era, and one of them wrote: The fantastic pillars and arches of fairy folk-lore may still be descried in the deep secluded glens of Thelemarken, undefaced with stucco, not propped by unsightly modern buttress. The harp of popular minstrelsy – though it hangs mouldering and mildewed with infrequency of use, its strings unbraced for want of cunning hands that can tune and strike them as the Scalds of Eld – may still now and then be heard sending forth its simple music. Sometimes this assumes the shape of a soothing lullaby to the sleep- ing babe, or an artless ballad of love-lorn swains, or an arch satire on rustic doings and foibles. Sometimes it swells into a symphony descriptive of the descent of Odin; or, in somewhat less Pindaric, and more Dibdin strain, it recounts the deeds of the rollicking, death-despising Vikings; while, anon, its numbers rise and fall with mysterious cadence as it strives to give a local habitation and a name to the dimly seen forms and antic pranks of the hol- low-backed Huldra crew.” (From The Oxonian in Thelemarken, or Notes of Travel in South-Western Norway in the Summers of 1856 and 1857, written by Frederick Metcalfe, Lincoln College, Oxford.) This was a typical Romantic way of describing a foreign culture. -

NISSWA-STAMMAN WORKSHOPS 2014 Scandinavian Instrumental

NISSWA-STAMMAN WORKSHOPS 2014 Scandinavian instrumental, singing and dance workshops, featuring top level musicians from Denmark, Sweden and Norway will take place on June 6, 2014 in and around Nisswa, Mn. You must sign up in advance for these. These workshops are offered in conjunction with Nisswa-stämman Scandinavian Folkmusic Festival, June 6, 7, 2014. Sessions are in 2 hours blocks. The first one starts at 10 a.m. and the second one starts at 1 p.m. For many locations a 'spelmans' lunch break is offered at noon. There are some sessions that are half day only....check the listings. Cost for the sessions is $20 each, or $35 for two sessions if they are from the same teacher. It is okay to register for a morning session from one teacher and and afternoon session from another. All locations are close enough together so it is possible to drive between them over lunchtime. All workshops are generally taught by ear and participants are encouraged to bring recording devices. The 'spelmans lunch' at many locations happens at noon, and consists of cold cuts, vegies, fruit, etc and cost an extra $5. (note - no lunch is provided at the dance workshops...but downtown Nisswa is right there with several restaurants available) After you signup you will receive more information about your workshop, including a detailed map for getting there. TO SIGN UP, PLEASE CONTACT JANET HILL - [email protected] or 218-259-4090. It is always possible that we may have trouble filling all the workshops with students, so two things need to happen: 1) everyone who took a workshop last year needs to return. -

Den Norske Kunsten Staar Fix Og Ferdig Paa Fjeldet”

Institutt for musikkvitenskap, UiO Litteratur MUS1301 V2010 1 "Den norske Kunsten staar fix og ferdig paa Fjeldet" av Olav Sæta Overskriftens p˚astand er tillagt Ole Bull, trolig omkring 1850, og kan vir- ke typisk for et av høydepunktene i den nasjonalromantiske perioden i v˚arkulturhistorie. Forutsetningen for dette var strømningene i europeisk ˚andslivfra siste del av 1700-tallet og framover, der tanker om, og følelse for, nasjonal identitet ble styrket, noe som fikk spesielt sterkt gjennomslag i kulturlivet. For musikkens del innebar dette oppfatninger om at en nasjons egen musikkarv burde utgjøre fundamentet for landets musikkliv. Den urbane ˚ands-og kultureliten, som forvaltet slike tanker, oppfattet ˚aleve i svært moderne tider preget av rotløshet og fremmedgjøring, der nasjonens rendyrkede musikalske arv bare kunne finnes igjen blant den enkle og na- turlige befolkningen p˚alandsbygda. Dette var mer enn rent ideologiske funderinger. Den musikalske arven ble oppfattet som en ˚andskraftnedlagt i hvert enkelt menneske { slik Johan Gottfried von Herder hadde hevdet i Tyskland, og slik Aasmund O. Vinje beskrev det her hjemme: Dei høyrde Tonar, som dei kjende var sine eigne. Det folkelige inspirerer Bulls utsagn om den norske Kunsten var særlig myntet p˚aden folkelige musikken og dansen, der hans eget engasjement vokste kraftig fra 1840- ˚ara.Han ans˚aat sl˚attemusikk p˚ahardingfele, og de gamle dansene halling og springar i variert utforming, var enest˚aende kunstverk i seg sjøl, slik han hadde opplevd dem utført av de beste utøverne i bygde-Norge. Hos andre kunstnere, og hos publikum, omfattet den nasjonale gløden i like stor grad teater-, dikter-, malerkunst og arkitektur, og ikke minst den næ- re samklangen som eksisterte mellom disse uttrykksformene p˚adenne tida. -

World Music Series, Karin Loberg Code, Harding Fiddle, October 5, 2015 Lawrence University

Lawrence University Lux Conservatory of Music Concert Programs Conservatory of Music 10-5-2015 8:00 PM World Music Series, Karin Loberg Code, Harding Fiddle, October 5, 2015 Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: http://lux.lawrence.edu/concertprograms Part of the Music Performance Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Lawrence University, "World Music Series, Karin Loberg Code, Harding Fiddle, October 5, 2015" (2015). Conservatory of Music Concert Programs. Program 12. http://lux.lawrence.edu/concertprograms/12 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conservatory of Music Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MUSIC SERIES Karin Loberg Code Harding Fiddle Karin Loberg Code Harding Fiddle October 5, 2015 • 8 p.m. Harper Hall, Music-Drama Center Bridal march from Nes Sjåheimen valdresspringar Lyarlått etter Ola Okshovd Mehanken valdresspringar Steinsruden telespringar Sølve-Knut hallingspringar Trulseguten halling Sistelått at Krøsshaugen lèt Jenta med Garde Slidreklukkelåtten Knut Ivarslåtten Vossavalsen Fykeruds farvel til Amerika No intermission The hardingfele, or Harding fiddle, is an indigenous Norwegian folk instrument used primarily to accompany a group of regional dances known as bygdedans. This tradition dates back to at least the mid-17th century, and has continued without interruption to the present day. Some of the physical features that distinguish the hardingfele from a violin are the shorter neck; deeply indented ƒ-holes; a thick, almost flat bridge; ornate decorations; and the presence of six to 10 strings. -

6.April 2019 På Sør-Aurdal Ungdomsskole, Bagn

6.april 2019 på Sør-Aurdal ungdomsskole, Bagn. Begnaljom spel- og dansarlag er arrangør av årets Valdreskappleik. Valdreskappleiken er lokalkappleik og runddansstemne for Valdres. Kappleiken går på omgang i lokallaga i Valdres, og blir arrangert om våren. Kappleiken går føre seg på dagtid, med finalekonsert og fest på kvelden. Hilme året rundt: konsert med Håkon Asheim og Henning Andersen kl 18.00, Glasshuset, Sør-Aurdal ungdomsskole, Bagn. Dei tek publikum med på ei musikalsk reise gjennom tidlaust lydarlæte og Aurdalsspel. Håkon Asheim har fordjupa seg i spelet etter Aurdalsspelemannen Ulrik i Jensestogun. Henning Andersen speler låttar frå heile Valdres, men har og mange spennande låttar frå Aurdal og Sør-Aurdal på repertoaret. Båe spelemennene har eit variert spel, og dei representerer kvar sin unike måte spele Valdresspel på. Merk at det må kjøpast eigen billett til denne konserten. Deltakarar, og publikum som har løyst billett til kappleiken, får rabatt. Billettar kan kjøpast på førehand på www.hilme.no eller under kappleiken. Konsertbilletten dekkjer også inngang på festen om kvelden. Sjå meir info under billettprisar. Arrangementet er på Glasshuset, Sør-Aurdal ungdomsskole på Bagn. Kappleiken: Førehandspåmelding så fort som mulig på e-post til [email protected] Hugs fullt namn, telefon, klasse og alder. Startliste blir lagt ut på facebooksida før kappleiken. Dersom du ikkje har meldt deg på førehand, men ynskjer å delta, ta kontakt med tevlingsleiar. Det kan vera høve til å delta likevel, dersom det er ledig plass. Kappleiken har totalt ni ulike klasser. Alle klasser, bortsett frå runddanstevlinga på kvelden, blir delt i junior og senior.