'A Limburgian,So Corrupt'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Putting Frisian Names on the Map

GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Putting Frisian names on the map Submitted by the Netherlands** * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Jasper Hogerwerf, Kadaster GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 Introduction Dutch is the national language of the Netherlands. It has official status throughout the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In addition, there are several other recognized languages. Papiamentu (or Papiamento) and English are formally used in the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom, while Low-Saxon and Limburgish are recognized as non-standardized regional languages, and Yiddish and Sinte Romani as non-territorial minority languages in the European part of the Kingdom. The Dutch Sign Language is formally recognized as well. The largest minority language is (West) Frisian or Frysk, an official language in the province of Friesland (Fryslân). Frisian is a West Germanic language closely related to the Saterland Frisian and North Frisian languages spoken in Germany. The Frisian languages as a group are closer related to English than to Dutch or German. Frisian is spoken as a mother tongue by about 55% of the population in the province of Friesland, which translates to some 350,000 native speakers. In many rural areas a large majority speaks Frisian, while most cities have a Dutch-speaking majority. A standardized Frisian orthography was established in 1879 and reformed in 1945, 1980 and 2015. -

'Limburgish' As a Regional Language in the European Charter For

The Status of ‘Limburgish’ as a Regional Language in the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages: A study on language policy, beliefs, and practices in Roermond Huub Ramakers (630512) Tilburg University School of Humanities Master Management of Cultural Diversity Thesis Supervisor : prof. dr. J.W.M. Kroon Second Reader : dr. J. Van Der Aa Date : 27-6-2016 Abstract This thesis deals with the implementation of The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) regarding Limburgish in the city of Roermond. In 1996, the dialect of Limburgish was accepted into, and recognized under part II of the ECRML. The Charter explicitly states that dialects of the majority language should not be considered. Limburgish however, through the ECRML gained the status of a Regional Language. To investigate the consequences of Limburgish being part of the ERCML, the focus of this thesis was narrowed down to the city of Roermond in Central-Limburg. The research question that guides this investigation runs as follows: “How did the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages materialize in the city of Roermond regarding the city’s actual language policies and practices and its inhabitants’ beliefs with respect to Limburgish?” The goal of the research was to investigate the policy regarding Limburgish at three different levels: as text, i.e. the ECRML as a policy document, as beliefs, i.e. the opinions and attitudes of inhabitants of Roermond regarding the ECRML, and as practices, i.e. the actual implementation of the ECRML in Roermond. Data collection included (1) a study of the ECRML as a document as well as journal articles, books, and other texts specifically related to the ECRML; (2) three interviews with key informants in the domains of administrative authorities and public services & cultural activities and facilities, education, and media in Roermond; (3) an online survey among more than 100 inhabitants of Roermond dealing with their attitudes and practices regarding Limburgish. -

Legitimating Limburgish: the Reproduction of Heritage

4 Legitimating Limburgish The Reproduction of Heritage Diana M. J. Camps1 1. Introduction A 2016 column in a Dutch regional newspaper, De Limburger, touted the following heading: “Limburgse taal: de verwarring blijft” (Limburgian lan- guage: the confusion remains). In its introduction, Geertjan Claessens, a jour- nalist, points to the fact that it has been nearly 20 years since Limburgish was recognized as a regional language under the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages (ECRML2) but asks “which language is recog- nized?” (Claessens 2016). In 1997, Limburgish, formerly considered a dialect of Dutch, was acknowledged by local and national authorities as a regional language under the ECRML. In his editorial, Claessens points to the multi- plicity of dialects that constitute Limburgish as a regional language, each with their own unique elements and nuances. As such, expert opinions about how to conceptualize Limburgish as a “language” still widely differ, and nego- tiations and tensions about how to write Limburgish continue. Despite the creation of an official spelling standard in 2003, Claessens asserts that these discussions about spelling norms will not see an end any time soon. Spelling was also highlighted in a Limburgian classroom I observed in 2014, where nearly a dozen adult students focused on the reading and writ- ing of their local Limburgian dialect. Rather than framing spelling as a potential point of debate, however, the teacher presents an instrumentalist view, stating: dit is een spelling en dat is als ‘t ware een technisch apparaat om de klanken zichtbaar te maken want dao geit ‘t om [. .]en dat is ‘T grote idee van de spelling [pause] de herkenbaarheid this is a spelling and that is in essence a technical device to make the sounds visible because that is what it is about [. -

Audience and the Use of Minority Languages on Twitter

Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media Audience and the Use of Minority Languages on Twitter Dong Nguyen and Dolf Trieschnigg Leonie Cornips University of Twente Meertens Institute Enschede, The Netherlands Amsterdam, The Netherlands {d.nguyen,d.trieschnigg}@utwente.nl [email protected] Abstract friends, colleagues) are collapsed into a single context (Mar- wick and boyd 2011). Users with public profiles on Twitter On Twitter, many users tweet in more than one lan- have potentially a limitless audience, but they often imagine guage. In this study, we examine the use of two Dutch minority languages. Users can engage with different an audience when writing tweets and may target tweets to audiences and by analyzing different types of tweets, different audiences (Marwick and boyd 2011). we find that characteristics of the audience influence We study Twitter users in two provinces in the Nether- whether a minority language is used. Furthermore, lands, where besides Dutch a minority language is spoken. while most tweets are written in Dutch, in conversations Frisian (spoken in Friesland) is recognized as an official users often switch to the minority language. language in the Netherlands. Also Limburgish (spoken in Limburg) – a group of what people call dialects – have re- Over 10% of the Twitter users tweet in more than one lan- ceived minor recognition by the Netherlands, a signatory guage (Hale 2014). Also within a single language, there is of the 1992 European Charter for Regional Languages or much geographical variation (Eisenstein et al. 2010). Every Languages of Minorities. There is a positive attitude to- user has his or her own linguistic repertoire which the indi- wards both minority languages, but their use has declined vidual user can draw linguistic elements or codes (language (Riemersma, Gorter, and Ytsma 2001; Cornips 2013). -

ARTS Aruþ 5OCIETY in FTANDERS and TI{E NETI{ERLANDS

ARTS AruÞ 5OCIETY IN FTANDERS AND TI{E NETI{ERLANDS L \ WE8'l'Vlu\AMSCH The Difference Between Language and Dialect in the Netherlands and Flanders IDIOTICON ILH.UI )Ml L.·L. l'flll::liiU Wh.l.ll, fl 1-"J'_I•I --·- ·- ·---·--- .. - 274 Perhaps the real puzzle is why there is so much variation. The small geographi- 041 UW •lAlllJ<J & •Ill' P. cal area of the Netherlands and Flanders is home to hundreds of dialects ac- cording to some counts -some of them mutually unintelligible, all of them di- 0 vided over two languages: Dutch and Frisian. Cl z In this delta area in the northwest corner of Europe variation has been in- grained from time immemorial. Even in the wildest nationalistic fantasies of f-. (/) the nineteenth century, the in habitants were descended not from one people, 0 but from at least three Germanic tribes who settled here: the Franks, the Sax- 0 ons and the Frisians. We also know that when these tribes set foot on it, the Flemish Brabant, the economic centres of the Southern Netherlands. In the seve n- z < area was by no means uninhabited. Even if Little is known about the previous teenth century a great many wealthy, industrious people also came to Holla nd from > inhabitants, there are traces of their language in present day Dutch. those areas, mainly to escape religious persecution. This substantially strength- u So from the very beginning the Linguistic Landscape here was also a delta, ened Holland 's position and introduced elements of the Antwerp dialects and oth- with influxes from elsewhere mixing with local elements in continually chang- ers into the dialects of Holland, making them look more like the standard language. -

NL 3Rd Evaluation Report Public

Strasbourg, 9 July 2008 ECRML (2008) 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN THE NETHERLANDS 3rd monitoring cycle A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by the Netherlands The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making Recommendations for improvements in its legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, established in accordance with Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to examine the real situation of the regional or minority languages in the State, to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers has adopted, in accordance with Article 15.1, an outline for the periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report shall be made public by the government concerned. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under its Part II and in more precise terms all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. -

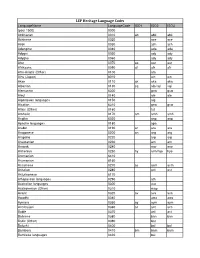

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Progressive Aspect in a Dutch-German-Limburgish Contact Variety

Progressive aspect in a Dutch-German-Limburgish contact variety Nantke Pecht (University of Maastricht) Keywords: progressive aspect, syntax, semantics, language-dialect contact, Germanic contact variety This talk presents a first analysis of progressive aspect in Cité Duits, a contact variety composed of features of Belgian Dutch, German and a Limburgish dialect. Cité Duits (lit. ‘mining district German’) developed among the locally-born children of immigrant miners of different European language backgrounds in the shared housing district of Eisden (B) in the 1930s. Nowadays, it is on the cusp of disappearing, with approximately ten speakers left, all of them men in their eighties. My contribution will be based on a corpus of audio data of spontaneous- like interactions (340 minutes) gathered by a method of sociolinguistic fieldwork (Labov 1972) in 2012/13 and 2015/16. By following the views postulated by Comrie (1976), Bybee and Dahl (1989) and Bybee et al. (1994), I consider aspect as a cross-linguistic category that exhibits a number of different realization strategies. An example from the data is the following: (1) (0313_152448: 84.31 - 88.01) de war(t) teleVIsie an gucke, he was television PROG lookINF flog ihm au(ch) de (au)AUge kaputt. flyPST him also the eye broken ‘He was watching television when his eye got hurt.’ In (1), the speaker reports a situation in the past where two events took place simultaneously. He first uses a progressive construction (war(t) + an + V-INF), indicating that the situation he referred to continued, and then switches to the simple past tense (flog). Progressive aspect is expressed here by means of an plus V-INF plus sein-FINITE ‘at V-INF be-FINITE’. -

Sixth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in Accordance with Article 15 of the Charter

Strasbourg, 18 June 2019 MIN-LANG (2019) PR 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Sixth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter NETHERLANDS Sixth report from the Netherlands: 2015-2018 Under article 15, paragraph 1, of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (Strasbourg, 5 November 1992) June 2019 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................4 2. LANGUAGES IN FOCUS ........................................................................................................................5 2.1 Frisian ............................................................................................................................................5 2.1.1 Use of Frisian Act ....................................................................................................................5 2.1.2 Advisory body on the Frisian language: DINGtiid ...................................................................5 2.1.3 Bestjoersôfspraak Fryske Taal en Kultuer (BFTK) ...................................................................7 2.1.4 Taalskipper Frysk ....................................................................................................................8 2.1.5 Frisian in education ................................................................................................................9 2.1.6 Working visits -

Measuring Dutch Dialect Speaking

Tilburg University Essays on economics of language and family economics Yao, Yuxin Publication date: 2017 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Yao, Y. (2017). Essays on economics of language and family economics. CentER, Center for Economic Research. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. sep. 2021 Essays on Economics of Language and Family Economics PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op dinsdag 5 september 2017 om 14.00 uur door Yuxin Yao geboren te Hubei, China. PROMOTIECOMMISSIE: PROMOTORES: Prof. -

The Wage Penalty of Dialect-Speaking

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Yao, Yuxin; van Ours, Jan C. Working Paper The Wage Penalty of Dialect-Speaking IZA Discussion Papers, No. 10333 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Yao, Yuxin; van Ours, Jan C. (2016) : The Wage Penalty of Dialect- Speaking, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 10333, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/149192 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IZA DP No. 10333 The Wage Penalty of Dialect-Speaking Yuxin Yao Jan C. van Ours October 2016 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Wage Penalty of Dialect-Speaking Yuxin Yao CentER, Tilburg University Jan C. -

Country and Language Codes for Hreflang Tags Country and Language Codes for Hreflang Tags

Country and language codes for hreflang tags Country and language codes for hreflang tags COUNTRY CODE LANGUAGE CODE Afghanistan AF Afar aa Åland Islands AX Afrikaans af Albania AL Akan ak Algeria DZ Albanian sq American Samoa AS Amharic am Andorra AD Arabic ar Angola AO Aragonese an Anguilla AI Armenian hy Antarctica AQ Assamese as Antigua and Barbuda AG Australian ac Argentina AR Avaric av Armenia AM Avestan ae Aruba AW Aymara ay Australia AU Azerbaijani az Austria AT Bambara bm Azerbaijan AZ Bashkir ba Bahamas BS Basque eu Bahrain BH Belarusian be Bangladesh BD Bengali, Bangla bn Barbados BB Bihari bh Belarus BY Bislama bi Belgium BE Bosnian bs Belize BZ Breton br Benin BJ Bulgarian bg Bermuda BM Burmese my Bhutan BT Catalan ca Bolivia (Plurinational State of) BO Chamorro ch Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba BQ Chechen ce Bosnia and Herzegovina BA Chichewa, Chewa, Nyanja ny Botswana BW Chinese zh Bouvet Island BV Chuvash cv Brazil BR Cornish kw British Indian Ocean Territory IO Corsican co Brunei Darussalam BN Cree cr Bulgaria BG Croatian hr Burkina Faso BF Czech cs Burundi BI Danish da Cambodia KH Divehi, Dhivehi, Maldivian dv Cameroon CM Dutch nl Canada CA Dzongkha dz Cabo Verde CV English en Cayman Islands KY Esperanto eo Central African Republic CF Estonian et Chad TD Ewe ee Chile CL Faroese fo China CN Fijian fj Christmas Island CX Finnish fi Cocos (Keeling) Islands CC French fr Colombia CO Fula, Fulah, Pulaar, Pular ff Comoros KM Galician gl Congo CG Georgian ka Congo (Democratic Republic of the) CD German de Cook Islands CK Greek