Stoned out of My Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

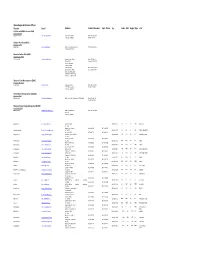

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt. Phone Fax Code ABLI RegionType Unit U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Alaska Region (FWS) HASKETT,GEOFFREY [email protected] 1011 East Tudor Road Phone: 907‐ 786‐3309 Anchorage, AK 99503 Fax: 907‐ 786‐3495 Naitonal Park Service(NPS) Alaska Region (NPS) MASICA,SUE [email protected] 240 West 5th Avenue,Suite 114 Phone:907‐644‐3510 Anchoorage,AK 99501 Bureau of Indian Affairs(BIA) Alaska Region (BIA) VIRDEN,EUGENE [email protected] Bureau of Indian Affairs Phone: 907‐586‐7177 PO Box 25520 Telefax: 907‐586‐7252 709 West 9th Street Juneau, AK 99802 Anchorage Agency Phone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Indian Affairs Telefax:907 271‐4477 3601 C Street Suite 1100 Anchorage, AK 99503‐5947 Telephone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Land Manangement (BLM) Alaska State Office (BLM) CRIBLEY,BUD [email protected] Alaska State Office Phone: 907‐271‐5960 222 W 7th Avenue #13 FAX: 907‐271‐3684 Anchorage, AK 99513 United States Geological Survey(USGS) Alaska Area (USGS) BARTELS,LESLIE lholland‐[email protected] 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508‐4626 Phone:907‐786‐7055 Fax: 907‐ 786‐7040 Bureau of Ocean Energy Management(BOEM) Alaska Region (BOEM) KENDALL,JAMES [email protected] 3801 Centerpoint Drive Phone: 907‐ 334‐5208 Suite 500 Anchorage, AK 99503 Ralph Moore [email protected] c/o Katmai NP&P (907) 246‐2116 ANIA ANTI AKR NPRES ANIAKCHAK P.O. Box 7 King Salmon, AK 99613 (907) 246‐3305 (907) 246‐2120 Jeanette Pomrenke [email protected] P.O. -

Welcome to the Nation's Capital Key Facts

WASHINGTON NATIONAL “THIS IS FOR MY GIRLS” KEY FACTS CATHEDRAL Proceeds from this song, has over 200 released in 2016, go to the FEDERAL DISTRICT DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA stained glass Peace Corps to support 62 windows; in one, million girls worldwide who a tiny piece of the are blocked from school. NAMED FOR NICKNAMES moon is hidden. George Washington, the • The Nation’s Capital first U.S. president • The District ANDREA DAVIS PINKNEY • City of Magnificent Intentions b.1963 The award-winning author FOUNDED IN BEST PLACE TO . 1790 of The Red Pencil founded See a dress sewn by Rosa the first African American UNITED STATES NATIONAL ARBORETUM Parks: Smithsonian National children’s book imprint at CITY POPULATION Museum of African American Here, bald eagles have a major publisher. History & Culture A DAY IN WASHINGTON D.C. PRESIDENT’S RESIDENCE raised eaglets in a 5-foot- 672,228 Each month, the president is wide by 6-foot-deep nest. billed for the family’s personal CITY AREA BRAGGING RIGHTS 9 AM In spring or fall, join a White House garden food and expenses—like 61 square miles D.C. has uber bragging rights tour. You might just hear the 70,000 bees at the EASTER toothpaste and shampoo! JACQUELINE AL GORE TARAJI P. HENSON DR. CHARLES DREW RUTH BADER GINSBURG as the home of the president! EGG ROLL JENKINS-NYE b.1948 b.1970 1904-1950 b.1933 White House’s own beehive. A bee’s wings beat Thousands of people 1921–2000 Born in D.C., this This Emmy-nominated This African American The second woman to TALLEST BUILDING some 11,000 times per minute! roll hard-boiled eggs FIRST LADIES’ This math whiz former vice president Empire actor from D.C. -

Building Stones of Our Nation's Capital

/h\q AaAjnyjspjopiBs / / \ jouami aqi (O^iqiii^eda . -*' ", - t »&? ?:,'. ..-. BUILDING STONES OF OUR NATION'S CAPITAL The U.S. Geological Survey has prepared this publication as an earth science educational tool and as an aid in understanding the history and physi cal development of Washington, D.C., the Nation's Capital. The buildings of our Nation's When choosing a building stone, Capital have been constructed with architects and planners use three char rocks from quarries throughout the acteristics to judge a stone's suitabili United States and many distant lands. ty. It should be pleasing to the eye; it Each building shows important fea should be easy to quarry and work; tures of various stones and the geolog and it should be durable. Today it is ic environment in which they were possible to obtain fine building stone formed. from many parts of the world, but the This booklet describes the source early builders of the city had to rely and appearance of many of the stones on materials from nearby sources. It used in building Washington, D.C. A was simply too difficult and expensive map and a walking tour guide are to move heavy materials like stone included to help you discover before the development of modern Washington's building stones on your transportation methods like trains and own. trucks. Ancient granitic rocks Metamorphosed sedimentary""" and volcanic rocks, chiefly schist and metagraywacke Metamorphic and igneous rocks Sand.gravel, and clay of Tertiary and Cretaceous age Drowned ice-age channel now filled with silt and clay Physiographic Provinces and Geologic and Geographic Features of the District of Columbia region. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

Lantern Slides SP 0025

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 What are Finding Aids? Finding aids are narrative guides to archival collections created by the repository to describe the contents of the material. They often provide much more detailed information than can be found in individual catalog records. Contents of finding aids often include short biographies or histories, processing notes, information about the size, scope, and material types included in the collection, guidance on how to navigate the collection, and an index to box and folder contents. What are Legacy Finding Aids? The following document is a legacy finding aid – a guide which has not been updated recently. Information may be outdated, such as the Historical Society’s contact information or exact box numbers for contents’ location within the collection. Legacy finding aids are a product of their times; language and terms may not reflect the Historical Society’s commitment to culturally sensitive and anti-racist language. This guide is provided in “as is” condition for immediate use by the public. This file will be replaced with an updated version when available. To learn more, please Visit DCHistory.org Email the Kiplinger Research Library at [email protected] (preferred) Call the Kiplinger Research Library at 202-516-1363 ext. 302 The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation’s capital. Founded in 1894, it serves a diverse audience through its collections, public programs, exhibits, and publications. THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

K. Savage, “The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight

The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Author(s): Kirk Savage Reviewed work(s): Source: Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Winter, 1987), pp. 225-242 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181181 . Accessed: 26/01/2012 09:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Winterthur Portfolio. http://www.jstor.org The Self-made Monument George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Kirk Savage HE 555-FOOT OBELISK on the Mall in Even in his own time Washington and the nation Washington, D.C., is one of the most con- he led were largely products of the collective im- spicuous structures in the world, standing agination. America was then-and to some extent alone on a grassy plain at the very core of national remains-an intangible thing, an idea: a voluntary power-approximately the intersection of the two compact of individuals rather than a family, tribe, great axes defined by the White House and the or race. -

Founding Fathers" in American History Dissertations

EVOLVING OUR HEROES: AN ANALYSIS OF FOUNDERS AND "FOUNDING FATHERS" IN AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATIONS John M. Stawicki A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2019 Committee: Andrew Schocket, Advisor Ruth Herndon Scott Martin © 2019 John Stawicki All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This thesis studies scholarly memory of the American founders and “Founding Fathers” via inclusion in American dissertations. Using eighty-one semi-randomly and diversely selected founders as case subjects to examine and trace how individual, group, and collective founder interest evolved over time, this thesis uniquely analyzes 20th and 21st Century Revolutionary American scholarship on the founders by dividing it five distinct periods, with the most recent period coinciding with “founders chic.” Using data analysis and topic modeling, this thesis engages three primary historiographic questions: What founders are most prevalent in Revolutionary scholarship? Are social, cultural, and “from below” histories increasing? And if said histories are increasing, are the “New Founders,” individuals only recently considered vital to the era, posited by these histories outnumbering the Top Seven Founders (George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine) in founder scholarship? The thesis concludes that the Top Seven Founders have always dominated founder dissertation scholarship, that social, cultural, and “from below” histories are increasing, and that social categorical and “New Founder” histories are steadily increasing as Top Seven Founder studies are slowly decreasing, trends that may shift the Revolutionary America field away from the Top Seven Founders in future years, but is not yet significantly doing so. -

National Treasure Movie Study.Pdf

Terms of use © Copyright 2019 Learn in Color. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. This file is for personal and classroom use only. You are not allowedto re- sell this packet or claim it as your own. You may not alter this file. You may photocopy it only for personal, non-commercial uses, such as your immediate family or classroom. If you have any questions, comments, problems, or future product suggestions, feel free to shoot me an e-mail! :) Movie Studies: Novel Studies: • The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler • I Am David by Anne Holm • The Emperor’s New Groove • Louisiana’s Way Home by Kate DiCa- • The Giver millo • The Greatest Showman • Merci Suarez Changes Gears by Meg • Holes Medina • Life is Beautiful • Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes • Meet the Robinsons by Jonathan Auxier • Mulan • Projekt 1065 by Alan Gratz • Newsies • Sweep by Jonathan Auxier • The Pursuit of Happyness • And more! • Secondhand Lions • The Sound of Music • Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory • The Zookeeper’s Wife • And more! Created by Samantha Shank E-mail: [email protected] Website: learnincolor.com Teachers Pay Teachers: teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Learn-In-Color Join facebook.com/learnincolormy Facebook community! Name: ________________________________________ 1. What is the Charlotte? Movie Quiz A. A train B. A car C. A ship D. An airplane 2. What do Ben, Riley, and Ian find on the Charlotte? A. A pipe B. A map C. Glasses D. A book 3. On the Charlotte, who wants to steal the Declaration of Independence? A. Ben B. Riley C. Sadusky D. -

George Washington: a New Man for a New Century

GEORGE WASHINGTON: A NEW MAN FOR A NEW CENTURY By Barry Schwartz George Washington never tolerated the notion, flaunted by some of his successors in the Presidential chair that the voice of the people, whatever its tone or its message, is the voice of God; nor was his political philosophy summed up in “keeping his ear to the ground, ” in order to catch from afar the ramblings of popular approval or dissent.... Will any one say that there is no need of such men now, or that the common people would not hear them gladly if once it were known that they dwelt among us? —The Nation, 18891 Every conception of the past is construed from the standpoint of the concerns and needs of the present.”2 Could the sociologist George Herbert Mead’s statement be applied to George Washington at the 1899 centennial of his death? Was Washington the same man at the turn of the twentieth century, when America was becoming an industrial democracy, as he was at the turn of the nineteenth, when the nation was still a rural republic? The title of the present essay suggests that the question has already been answered, but the matter is more complex than that. Because any historical object appears differently against a new background, Washington’s character and achievements necessarily assumed new meaning from the Jacksonian era and Civil War through the Industrial Revolution. Washington’s changing image, however, is only one part of this story. Focusing on the first two decades of the twentieth century, the other part of the story—“Washington’s unchanging image”—must also be considered. -

INDEX HB Pages Qfinal Copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 1 the National Parks: Index 2001-2003

INDEX_HB_Pages_QFinal copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 1 The National Parks: Index 2001-2003 Revised to Include the Actions of the 106th Congress ending December 31, 2000 Produced by the Office of Public Affairs and Harpers Ferry Center Division of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1 INDEX_HB_Pages_QFinal copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 2 About this Book This index is a complete administrative listing of the National Park System’s areas and related areas. It is revised biennially to reflect congressional actions. The entries, grouped by state, include administrative addresses and phone numbers, dates of au- thorization and establishment, boundary change dates, acreages, and brief statements explaining the areas’ national significance. This book is not intended as a guide for park visitors. There is no information regarding campgrounds, trails, visitor services, hours, etc. Those needing such information can visit each area’s web site, accessible through the National Park Service ParkNet home page (www.nps.gov). The Mission of the National Park Service The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future genera- tions. The National Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing