Menkes Disease: What a Multidisciplinary Approach Can Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mackenzie's Mission Gene & Condition List

Mackenzie’s Mission Gene & Condition List What conditions are being screened for in Mackenzie’s Mission? Genetic carrier screening offered through this research study has been carefully developed. It is focused on providing people with information about their chance of having children with a severe genetic condition occurring in childhood. The screening is designed to provide genetic information that is relevant and useful, and to minimise uncertain and unclear information. How the conditions and genes are selected The Mackenzie’s Mission reproductive genetic carrier screen currently includes approximately 1300 genes which are associated with about 750 conditions. The reason there are fewer conditions than genes is that some genetic conditions can be caused by changes in more than one gene. The gene list is reviewed regularly. To select the conditions and genes to be screened, a committee comprised of experts in genetics and screening was established including: clinical geneticists, genetic scientists, a genetic pathologist, genetic counsellors, an ethicist and a parent of a child with a genetic condition. The following criteria were developed and are used to select the genes to be included: • Screening the gene is technically possible using currently available technology • The gene is known to cause a genetic condition • The condition affects people in childhood • The condition has a serious impact on a person’s quality of life and/or is life-limiting o For many of the conditions there is no treatment or the treatment is very burdensome for the child and their family. For some conditions very early diagnosis and treatment can make a difference for the child. -

Centometabolic® COMBINING GENETIC and BIOCHEMICAL TESTING for the FAST and COMPREHENSIVE DIAGNOSTIC of METABOLIC DISORDERS

CentoMetabolic® COMBINING GENETIC AND BIOCHEMICAL TESTING FOR THE FAST AND COMPREHENSIVE DIAGNOSTIC OF METABOLIC DISORDERS GENE ASSOCIATED DISEASE(S) ABCA1 HDL deficiency, familial, 1; Tangier disease ABCB4 Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 3 ABCC2 Dubin-Johnson syndrome ABCD1 Adrenoleukodystrophy; Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult ABCD4 Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type ABCG5 Sitosterolemia 2 ABCG8 Sitosterolemia 1 ACAT1 Alpha-methylacetoacetic aciduria ADA Adenosine deaminase deficiency AGA Aspartylglucosaminuria AGL Glycogen storage disease IIIa; Glycogen storage disease IIIb AGPS Rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata, type 3 AGXT Hyperoxaluria, primary, type 1 ALAD Porphyria, acute hepatic ALAS2 Anemia, sideroblastic, 1; Protoporphyria, erythropoietic, X-linked ALDH4A1 Hyperprolinemia, type II ALDOA Glycogen storage disease XII ALDOB Fructose intolerance, hereditary ALG3 Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Id ALPL Hypophosphatasia, adult; Hypophosphatasia, childhood; Hypophosphatasia, infantile; Odontohypophosphatasia ANTXR2 Hyaline fibromatosis syndrome APOA2 Hypercholesterolemia, familial, modifier of APOA5 Hyperchylomicronemia, late-onset APOB Hypercholesterolemia, familial, 2 APOC2 Hyperlipoproteinemia, type Ib APOE Sea-blue histiocyte disease; Hyperlipoproteinemia, type III ARG1 Argininemia ARSA Metachromatic leukodystrophy ARSB Mucopolysaccharidosis type VI (Maroteaux-Lamy) 1 GENE ASSOCIATED DISEASE(S) ASAH1 Farber lipogranulomatosis; Spinal muscular atrophy with progressive myoclonic epilepsy -

Pili Torti: a Feature of Numerous Congenital and Acquired Conditions

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Pili Torti: A Feature of Numerous Congenital and Acquired Conditions Aleksandra Hoffmann 1 , Anna Wa´skiel-Burnat 1,*, Jakub Z˙ ółkiewicz 1 , Leszek Blicharz 1, Adriana Rakowska 1, Mohamad Goldust 2 , Małgorzata Olszewska 1 and Lidia Rudnicka 1 1 Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Warsaw, Koszykowa 82A, 02-008 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (J.Z.);˙ [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (M.O.); [email protected] (L.R.) 2 Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University, 55122 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-5021-324; Fax: +48-22-824-2200 Abstract: Pili torti is a rare condition characterized by the presence of the hair shaft, which is flattened at irregular intervals and twisted 180◦ along its long axis. It is a form of hair shaft disorder with increased fragility. The condition is classified into inherited and acquired. Inherited forms may be either isolated or associated with numerous genetic diseases or syndromes (e.g., Menkes disease, Björnstad syndrome, Netherton syndrome, and Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome). Moreover, pili torti may be a feature of various ectodermal dysplasias (such as Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome and Ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate syndrome). Acquired pili torti was described in numerous forms of alopecia (e.g., lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, dissecting Citation: Hoffmann, A.; cellulitis, folliculitis decalvans, alopecia areata) as well as neoplastic and systemic diseases (such Wa´skiel-Burnat,A.; Zółkiewicz,˙ J.; as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, scalp metastasis of breast cancer, anorexia nervosa, malnutrition, Blicharz, L.; Rakowska, A.; Goldust, M.; Olszewska, M.; Rudnicka, L. -

Avero® Exon Global 280+ Genes

Avero® Exon Global 280+ genes CARRIER DETECTION RESIDUAL GENE DISORDER NAME ETHNICITY FREQUENCY RATE RISK ABCB11 Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, type II General Population 1 in 158 99% 1 in 15701 ABCC8 Familial hyperinsulinism, ABCC8-related General Population 1 in 112 99% 1 in 11101 Ashkenazi Jewish 1 in 52 99% 1 in 5101 Finnish 1 in 29 99% 1 in 2801 ABCD1 Adrenoleukodystrophy, X-linked General Population 1 in 10500 99% 1 in 1049901 Sephardic Jewish 1 in 10500 99% 1 in 1049901 ACAD9 Riboflavin responsive complex 1 deficiency (acyl-coenzyme General Population <1 in 500 99% 1 in 49901 dehydrogenase 9 deficiency) ACADM Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency General Population 1 in 35 99% 1 in 3401 Asian 1 in 178 99% 1 in 17701 Caucasian 1 in 64 99% 1 in 6300 ACADVL Very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency General Population 1 in 86 99% 1 in 8500 Asian 1 in 194 99% 1 in 19301 Caucasian 1 in 88 99% 1 in 8700 ACAT1 Beta-ketothiolase deficiency General Population 1 in 347 99% 1 in 34601 Asian 1 in 289 99% 1 in 28801 Caucasian 1 in 354 99% 1 in 35301 ACOX1 Acyl-CoA oxidase I deficiency General Population <1 in 500 99% 1 in 49901 ACSF3 Combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria General Population 1 in 86 99% 1 in 8500 ADA Adenosine deaminase deficiency General Population 1 in 224 99% 1 in 22301 ADAMTS2 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, type VIIC General Population <1 in 500 99% 1 in 49901 Ashkenazi Jewish 1 in 248 99% 1 in 24701 6221 Riverside Drive, Suite 119, Irving, TX 75039 I Tel 877.232.9924 I averodx.com ©2020 Avero Diagnostics. -

Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 24 (2020) 100625

Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 24 (2020) 100625 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ymgmr Targeted next generation sequencing for newborn screening of Menkes T disease ⁎ Richard B. Parada,1, Stephen G. Kalerb,e, ,1, Evan Maucelic, Tanya Sokolskyc,d, Ling Yib, Arindam Bhattacharjeec,d a Department of Pediatric Newborn Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States of America b Section on Translational Neuroscience, Molecular Medicine Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, United States of America c Parabase Genomics, Inc., Boston, MA, United States of America d Baebies, Inc., Durham, NC, United States of America e Center for Gene Therapy, Abigail Wexner Research Institute, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Purpose: Population-based newborn screening (NBS) allows early detection and treatment of inherited disorders. Menkes disease For certain medically-actionable conditions, however, NBS is limited by the absence of reliable biochemical ATP7A signatures amenable to detection by current platforms. We sought to assess the analytic validity of an ATP7A Molecular genetics targeted next generation DNA sequencing assay as a potential newborn screen for one such disorder, Menkes Targeted next generation sequencing disease. Dried blood spots Methods: Dried blood spots from control or Menkes disease subjects (n = 22) were blindly analyzed for pa- Newborn screening thogenic variants in the copper transport gene, ATP7A. The analytical method was optimized to minimize cost and provide rapid turnaround time. Results: The algorithm correctly identified pathogenic ATP7A variants, including missense, nonsense, small insertions/deletions, and large copy number variants, in 21/22 (95.5%) of subjects, one of whom had incon- clusive diagnostic sequencing previously. -

Download CGT Exome V2.0

CGT Exome version 2. -

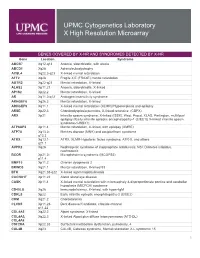

Genes Covered and Disorders Detected by X-HR Microarray

UPMC Cytogenetics Laboratory X High Resolution Microarray GENES COVERED BY X-HR AND SYNDROMES DETECTED BY X-HR Gene Location Syndrome ABCB7 Xq12-q13 Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia ABCD1 Xq28 Adrenoleukodystrophy ACSL4 Xq22.3-q23 X-linked mental retardation AFF2 Xq28 Fragile X E (FRAXE) mental retardation AGTR2 Xq22-q23 Mental retardation, X-linked ALAS2 Xp11.21 Anemia, sideroblastic, X-linked AP1S2 Xp22.2 Mental retardation, X-linked AR Xq11.2-q12 Androgen insensitivity syndrome ARHGEF6 Xq26.3 Mental retardation, X-linked ARHGEF9 Xq11.1 X-linked mental retardation (XLMR)//Hyperekplexia and epilepsy ARSE Xp22.3 Chondrodysplasia punctata, X-linked recessive (CDPX) ARX Xp21 Infantile spasm syndrome, X-linked (ISSX), West, Proud, XLAG, Partington, multifocal epilepsy //Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-1 (EIEE1)( X-linked infantile spasm syndrome-1-ISSX1) ATP6AP2 Xp11.4 Mental retardation, X-linked, with epilepsy (XMRE) ATP7A Xq13.2- Menkes disease (MNK) and occipital horn syndrome q13.3 ATRX Xq13.1- ATRX, XLMR-Hypotonic facies syndrome, ATR-X, and others q21.1 AVPR2 Xq28 Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis; NSI; Diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic BCOR Xp21.2- Microphthalmia syndromic (MCOPS2) p11.4 BMP15 Xp11.2 Ovarian dysgenesis 2 BRWD3 Xq21.1 Mental retardation, X-linked 93 BTK Xq21.33-q22 X-linked agammaglobulinemia CACNA1F Xp11.23 Aland Island eye disease CASK Xp11.4 X-linked mental retardation with microcephaly & disproportionate pontine and cerebellar hypoplasia (MICPCH) syndrome CD40LG Xq26 Immunodeficiency, -

ATP7A Sequencing for Menkes Disease and Occipital Horn Syndrome

ATP7A sequencing for Menkes disease and occipital horn syndrome Clinical Features: ATP7A mutations confer phenotypic heterogeneity by displaying two distinct disorders: Menkes disease [OMIM #309400] o Clinical findings: mental retardation, hypotonia, seizures, failure to thrive, vascular tortuosity, wormian bones, metaphyseal spurring, bladder diverticulae, pectus excavatum, skin laxity o Pathognomonic feature: pili torti o The mean survival is 3 years; major cause of death is respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia. Occipital Horn syndrome (OHS) or X-linked Cutis Laxa (formerly known as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IX) [OMIM #304150] o Clinical findings: bilateral occipital exostoses of the skull (occipital horns), long neck, high arched palate, long face, high forehead, skin and joint laxity, dysautonomia, bladder diverticula, inguinal hernias, vascular tortuosity, normal or slightly delayed intelligence o Pathognomonic feature: Pili torti o With appropriate treatment, survival is extended into adulthood. These disorders are thought to be within the same spectrum of copper metabolism impairment, OHS being the milder of the two. Some patients exhibit mild Menkes disease with severity in the middle of this spectrum. Pili torti is usually present in all patients within the spectrum. Carrier females do not typically have symptoms, but ~50% have been reported to have patches of pili torti. Diagnosis: Copper levels are decreased in individuals with this spectrum of copper metabolism impairment (<60µg/dL). Ceruloplasmin levels are also diminished (30-150mg/L). Unfortunately, healthy newborns have copper and ceruloplasmin levels ranging between 20-70µg/dL and 50-220mg/L, respectively. For this reason, other clinical features must be taken into account while attempting to diagnose a newborn. -

Genpanel for Arvelige Nevropatier V01

12/18/2020 Genpanel for arvelige nevropatier v01 Avdeling for medisinsk genetikk Genpanel for arvelige nevropatier Genpanel, versjon v01 * Enkelte genomiske regioner har lav eller ingen sekvensdekning ved eksomsekvensering. Dette skyldes at de har stor likhet med andre områder i genomet, slik at spesifikk gjenkjennelse av disse områdene og påvisning av varianter i disse områdene, blir vanskelig og upålitelig. Disse genetiske regionene har vi identifisert ved å benytte USCS segmental duplication hvor områder større enn 1 kb og ≥90% likhet med andre regioner i genomet, gjenkjennes (https://genome.ucsc.edu). For noen gener ligger alle ekson i områder med segmentale duplikasjoner: SORD Vi gjør oppmerksom på at ved identifiseringav ekson oppstrøms for startkodon kan eksonnummereringen endres uten at transkript ID endres. Avdelingens websider har en full oversikt over områder som er affisert av segmentale duplikasjoner. ** Transkriptets kodende ekson. Ekson Gen Gen affisert (HGNC (HGNC Transkript Ekson** Fenotype av symbol) ID) segdup* AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 1-16 Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 2-21 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 29 OMIM ABCA1 29 NM_005502.3 2-50 Tangier disease OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 7-10 1-10 Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABHD12 15868 NM_001042472.2 1-13 Polyneuropathy, hearing loss, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa, and cataract OMIM file:///data/Nevropati_v01-web.html 1/19 12/18/2020 Genpanel for arvelige -

Carrier Screen Genes List

Gene Disease ABCB11 Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 ABCB11 Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 ABCC2 Dubin-Johnson syndrome ABCC8 Diabetes, noninsulin dependent ABCC8 Diabetes, permanent neonatal ABCC8 Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, familial, 1 ABCC8 Hypoglycemia, infantile ABCD1 Adrenoleukodystrophy ACADM Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of ACADS Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of ACADVL Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, very long-chain, deficiency of ACAT1 Alpha-methylacetoacetic aciduria ACOX1 Peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase deficiency ACTA1 Myopathy congenital, with fiber-type disproportion ACTA1 Nemaline myopathy 3, AD or recessive ADA Severe combined immunodeficiency due to ADA deficiency ADAMTS2 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome AGA Aspartylglucosaminuria AGL Glycogen storage disease IIIa, IIb AGXT Hyperoxaluria, primary, type 1 AHCY Hypermethioninemia with deficiency of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome , type I, with or without reversible metaphyseal AIRE dysplasia ALDH3A2 Sjogren-Larsson syndrome ALDH4A1 Hyperprolinemia type II ALDOB Fructose intolerance, hereditary ALG6 Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic ALPL Hypophosphatasia AMH Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome, type I AMHR2 Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome, type II AMPD1 Myopathy due to myoadenylate deaminase deficiency AMT Glycine encephalopathy AR Androgen insensitivity AR Androgen insensitivity AR Hypospadias AR Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy of Kennedy ARG1 Argininemia ARL13B Joubert -

Copper Toxicity Associated with an ATP7A-Related Complex Phenotype

Pediatric Neurology 119 (2021) 40e44 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pediatric Neurology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pnu Short Communication Copper Toxicity Associated With an ATP7A-Related Complex Phenotype Daniel Natera-de Benito, MD, PhD a, Abel Sola, MSc b, Paulo Rego Sousa, MD a, c, Susana Boronat, MD, PhD d, Jessica Exposito-Escudero, MD a, Laura Carrera-García, MD a, Carlos Ortez, MD a, Cristina Jou, MD a, e, f, Jordi Muchart, MD g, Monica Rebollo, MD g, Judith Armstrong, PhD a, f, h, Jaume Colomer, MD, PhD a, Angels Garcia-Cazorla, MD, PhD f, i, Janet Hoenicka, PhD b, f, * y y Francesc Palau, MD, PhD b, f, h, j, , , Andres Nascimento, MD a, f, a Neuromuscular Unit, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu and Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain b Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Molecular Medicine e IPER, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain c Pediatric Neurology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Hospital Central do Funchal, Funchal, Portugal d Department of Pediatrics, Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain e Department of Pathology, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain f Center for Biomedical Research Network on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), ISCIII, Madrid, Spain g Department of Radiology, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain h Department of Genetic and Molecular Medicine e IPER, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain i Department of Pediatric Neurology, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain j Clinic Institute of Medicine & Dermatology, Hospital Clínic, and Division of Pediatrics, University of Barcelona School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Barcelona, Spain article info abstract Article history: Background: The ATP7A gene encodes a copper transporter whose mutations cause Menkes disease, Received 9 November 2020 occipital horn syndrome (OHS), and, less frequently, ATP7A-related distal hereditary motor neuropathy Accepted 17 March 2021 Available online 26 March 2021 (dHMN). -

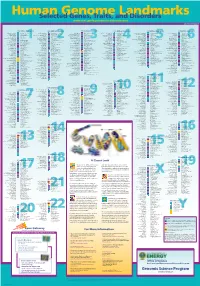

Genomeposter2009.Pdf

Fold HumanSelected Genome Genes, Traits, and Landmarks Disorders www.ornl.gov/hgmis/posters/chromosome genomics.energy.