A Phenotype Map of the Mouse X Chromosome: Models for Human X-Linked Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exceptional Conservation of Horse–Human Gene Order on X Chromosome Revealed by High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping

Exceptional conservation of horse–human gene order on X chromosome revealed by high-resolution radiation hybrid mapping Terje Raudsepp*†, Eun-Joon Lee*†, Srinivas R. Kata‡, Candice Brinkmeyer*, James R. Mickelson§, Loren C. Skow*, James E. Womack‡, and Bhanu P. Chowdhary*¶ʈ *Department of Veterinary Anatomy and Public Health, ‡Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, and ¶Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Life Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; and §Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Minnesota, 295f AS͞VM, St. Paul, MN 55108 Contributed by James E. Womack, December 30, 2003 Development of a dense map of the horse genome is key to efforts ciated with the traits, once they are mapped by genetic linkage aimed at identifying genes controlling health, reproduction, and analyses with highly polymorphic markers. performance. We herein report a high-resolution gene map of the The X chromosome is the most conserved mammalian chro- horse (Equus caballus) X chromosome (ECAX) generated by devel- mosome (18, 19). Extensive comparisons of structure, organi- oping and typing 116 gene-specific and 12 short tandem repeat zation, and gene content of this chromosome in evolutionarily -markers on the 5,000-rad horse ؋ hamster whole-genome radia- diverse mammals have revealed a remarkable degree of conser tion hybrid panel and mapping 29 gene loci by fluorescence in situ vation (20–22). Until now, the chromosome has been best hybridization. The human X chromosome sequence was used as a studied in humans and mice, where the focus of research has template to select genes at 1-Mb intervals to develop equine been the intriguing patterns of X inactivation and the involve- orthologs. -

The Inherited Metabolic Disorders News

The Inherited Metabolic Disorders News Summer 2011 Volume 8 Issue 2 From the Editor I hope everyone is enjoying their summer thus far! Our 8th annual Metabolic Family Day and 7th annual Low In this Issue Protein Cooking Demonstration were once again a huge success. See the section ”What’s New” on page 9 for a full report of the events, as well as pictures. ♦ From the Editor…1 As always, your suggestions and stories are welcome. Please contact me by email: [email protected] or telephone 519-685-8453 if you wish to contribute to the ♦ From Dr. Chitra Prasad…1 newsletter. I hope everyone has a safe and happy summer! ♦ Personal Stories… 2 Janice Little ♦ Featured This Issue … 4 From Dr Chitra Prasad ♦ Suzanne’s Corner… 6 Dear Friends, ♦ What’s New… 8 Hope you all are having a wonderful summer. We had a great metabolic family workshop with around 198 registrants this year. This was truly phenomenal. Thanks to all the team members and ♦ Research & Presentations … 13 the families in the planning committee for doing such a fantastic job. I was really touched when one of our young metabolic patients told her parents that she would like to attend the ♦ How to Make a Donation… 14 metabolic family workshop! Please see some of the highlights of the metabolic workshop in the newsletter for those who could not make it. The speeches by our youth (Sadiq, Leanna and Laura) ♦ Contact Information … 15 were appreciated by everyone. Big thanks to Jill Tosswill (our previous social worker) who coordinated their talks. -

Roles and Mechanisms of Kinesin-6 KIF20A in Spindle Organization During Cell Division T ⁎ Wen-Da Wu, Kai-Wei Yu, Ning Zhong, Yu Xiao, Zhen-Yu She

European Journal of Cell Biology 98 (2019) 74–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Cell Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejcb Review Roles and mechanisms of Kinesin-6 KIF20A in spindle organization during cell division T ⁎ Wen-Da Wu, Kai-Wei Yu, Ning Zhong, Yu Xiao, Zhen-Yu She Department of Cell Biology and Genetics/Center for Cell and Developmental Biology, The School of Basic Medical Sciences, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, Fujian 350108, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Mitotic kinesin is crucial for spindle assembly and chromosome segregation in cell division. KIF20A/MKlp2, a Kinesin-6 member of kinesin-6 subfamily, plays important roles in the central spindle organization at anaphase and cy- KIF20A tokinesis. In this review, we briefly introduce the discovery and classification of kinesin-6 motors in model Microtubule organisms, and summarize the biochemical features and mechanics of KIF20A proteins. We emphasize the Anaphase complicated interactions of KIF20A with partner proteins, including MKlp1, Plk1 and Rab6. Particularly, we Spindle assembly highlight the regulation of Cdk1 and chromosomal passenger complex on kinesin-6 KIF20A at late stage of Mitosis mitosis. We summarized the multiple functions of KIF20A in central spindle assembly and the formation of cleavage furrow in both mitosis and meiosis. In addition, we conclude the expression patterns of KIF20A in tumorigenesis and its applications in tumor therapy. 1. Introduction kinesin superfamily proteins (Miki et al., 2005). Kinesin-6 subfamily is comprised of KIF20A (Lawrence et al., 2004), KIF20B (MPP1) Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs) are molecular motors that (Kamimoto et al., 2001; Matsumoto-Taniura et al., 1996; Westendorf mediate the transport of various cargos, including the newly synthe- et al., 1994) and MKlp1 (Lawrence et al., 2004; Nislow et al., 1990; sized protein complexes, vesicles and mRNAs along the microtubule Sellitto and Kuriyama, 1988). -

Menkes Disease in 5 Siblings

Cu(e) the balancing act: Copper homeostasis explored in 5 siblings Poster with variable clinical course 595 Sonia A Varghese MD MPH MBA and Yael Shiloh-Malawsky MD Objective Methods Case Presentation Discussion v Present a unique variation of v Review literature describing v The graph below depicts the phenotypic spectrum seen in the 5 brothers v ATP7A mutations produce a clinical spectrum phenotype and course in siblings copper transport disorders v Mom is a known carrier of ATP7A mutation v Siblings 1, 2, and 5 follow a more classic with Menkes Disease (MD) v Apply findings to our case of five v There is limited information on the siblings who were not seen at UNC Menke’s course, while siblings 3 and 4 exhibit affected siblings v The 6th sibling is the youngest and is a healthy female infant (not included here) a phenotypic variation Sibling: v This variation is suggestive of a milder form of Background Treatment birth Presentation Exam Diagnostic testing Outcomes Copper Histidine Menkes such as occipital horn syndrome with v Mutations in ATP7A: copper deficiency order D: 16mos residual copper transport function (Menkes disease) O/AD: 1 Infancy/12mos N/A N/A No Brain v Siblings 3 and 4 had improvement with copper v Mutations in ATP7B: copper overload FTT, Seizures, DD hemorrhage supplementation, however declined when off (Wilson disease) O/AD: Infancy/NA D: 13mos supplementation -suggesting residual ATP7A v The amount of residual functioning 2 N/A N/A No FTT, FTT copper transport function copper transport influences disease Meningitis -

BMC Biology Biomed Central

BMC Biology BioMed Central Research article Open Access Normal histone modifications on the inactive X chromosome in ICF and Rett syndrome cells: implications for methyl-CpG binding proteins Stanley M Gartler*1,2, Kartik R Varadarajan2, Ping Luo2, Theresa K Canfield2, Jeff Traynor3, Uta Francke3 and R Scott Hansen2 Address: 1Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA and 3Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA Email: Stanley M Gartler* - [email protected]; Kartik R Varadarajan - [email protected]; Ping Luo - [email protected]; Theresa K Canfield - [email protected]; Jeff Traynor - [email protected]; Uta Francke - [email protected]; R Scott Hansen - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 20 September 2004 Received: 23 June 2004 Accepted: 20 September 2004 BMC Biology 2004, 2:21 doi:10.1186/1741-7007-2-21 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/2/21 © 2004 Gartler et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: In mammals, there is evidence suggesting that methyl-CpG binding proteins may play a significant role in histone modification through their association with modification complexes that can deacetylate and/or methylate nucleosomes in the proximity of methylated DNA. We examined this idea for the X chromosome by studying histone modifications on the X chromosome in normal cells and in cells from patients with ICF syndrome (Immune deficiency, Centromeric region instability, and Facial anomalies syndrome). -

Not Just Another Scaffolding Protein Family: the Multifaceted Mpps

molecules Review Not Just Another Scaffolding Protein Family: The Multifaceted MPPs 1, 1, 1 Agnieszka Chytła y , Weronika Gajdzik-Nowak y , Paulina Olszewska , Agnieszka Biernatowska 1 , Aleksander F. Sikorski 2 and Aleksander Czogalla 1,* 1 Department of Cytobiochemistry, Faculty of Biotechnology, University of Wroclaw, 50-383 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (W.G.-N.); [email protected] (P.O.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Research and Development Center, Regional Specialist Hospital, Kamie´nskiego73a, 51-154 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71375-6356 These authors contribute equally. y Academic Editor: Luís M.S. Loura Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Membrane palmitoylated proteins (MPPs) are a subfamily of a larger group of multidomain proteins, namely, membrane-associated guanylate kinases (MAGUKs). The ubiquitous expression and multidomain structure of MPPs provide the ability to form diverse protein complexes at the cell membranes, which are involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including establishing the proper cell structure, polarity and cell adhesion. The formation of MPP-dependent complexes in various cell types seems to be based on similar principles, but involves members of different protein groups, such as 4.1-ezrin-radixin-moesin (FERM) domain-containing proteins, polarity proteins or other MAGUKs, showing their multifaceted nature. In this review, we discuss the function of the MPP family in the formation of multiple protein complexes. Notably, we depict their significant role for cell physiology, as the loss of interactions between proteins involved in the complex has a variety of negative consequences. -

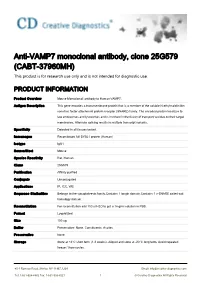

Anti-VAMP7 Monoclonal Antibody, Clone 25G579 (CABT-37960MH) This Product Is for Research Use Only and Is Not Intended for Diagnostic Use

Anti-VAMP7 monoclonal antibody, clone 25G579 (CABT-37960MH) This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic use. PRODUCT INFORMATION Product Overview Mouse Monoclonall antibody to Human VAMP7. Antigen Description This gene encodes a transmembrane protein that is a member of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide- sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) family. The encoded protein localizes to late endosomes and lysosomes and is involved in the fusion of transport vesicles to their target membranes. Alternate splicing results in multiple transcript variants. Specificity Detected in all tissues tested. Immunogen Recombinant full SYBL1 protein (Human) Isotype IgG1 Source/Host Mouse Species Reactivity Rat, Human Clone 25G579 Purification Affinity purified Conjugate Unconjugated Applications IP, ICC, WB Sequence Similarities Belongs to the synaptobrevin family.Contains 1 longin domain.Contains 1 v-SNARE coiled-coil homology domain. Reconstitution For reconstitution add 100 ul H2O to get a 1mg/ml solution in PBS. Format Lyophilized Size 100 ug Buffer Preservative: None. Constituents: Ascites Preservative None Storage Store at +4°C short term (1-2 weeks). Aliquot and store at -20°C long term. Avoid repeated freeze / thaw cycles. 45-1 Ramsey Road, Shirley, NY 11967, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: 1-631-624-4882 Fax: 1-631-938-8221 1 © Creative Diagnostics All Rights Reserved GENE INFORMATION Gene Name VAMP7 vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 [ Homo sapiens ] Official Symbol VAMP7 Synonyms VAMP7; vesicle-associated -

Opposite Deletions/Duplications of the X Chromosome: Two Novel Reciprocal Rearrangements

European Journal of Human Genetics (2000) 8, 63–70 © 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 1018–4813/00 $15.00 y www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Opposite deletions/duplications of the X chromosome: two novel reciprocal rearrangements Sabrina Giglio1, Barbara Pirola1,2 , Giulia Arrigo2, Paolo Dagrada3, Barbara Bardoni1, Franca Bernardi4, Giovanni Russo5, Luisa Argentiero3, Antonino Forabosco6, Romeo Carrozzo7 and Orsetta Zuffardi1,2 1Biologia Generale e Genetica Medica, Universit`a di Pavia, Pavia; 2Laboratorio di Citogenetica, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan; 3Citogenetica, ASL Provincia di Lodi, Lodi; 4Servizio Patologia Genetica e Prenatale, Ospedale Borgo Roma, Verona; 5Clinica Pediatria III, Universit`a di Milano, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan; 6Istologia, Embriologia e Genetica, Universit`a di Modena, Modena; 7Servizio di Genetica Medica, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy Paralogous sequences on the same chromosome allow refolding of the chromosome into itself and homologous recombination. Recombinant chromosomes have microscopic or submicroscopic rearrangements according to the distance between repeats. Examples are the submicroscopic inversions of factor VIII, of the IDS gene and of the FLN1/emerin region, all resulting from misalignment of inverted repeats, and double recombination. Most of these inversions are of paternal origin possibly because the X chromosome at male meiosis is free to refold into itself for most of its length. We report on two de novo rearrangements of the X chromosome found in four hypogonadic females. Two of them had an X chromosome deleted for most of Xp and duplicated for a portion of Xq and two had the opposite rearrangement (class I and class II rearrangements, respectively). The breakpoints were defined at the level of contiguous YACs. -

Discovery of Candidate Genes for Stallion Fertility from the Horse Y Chromosome

DISCOVERY OF CANDIDATE GENES FOR STALLION FERTILITY FROM THE HORSE Y CHROMOSOME A Dissertation by NANDINA PARIA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2009 Major Subject: Biomedical Sciences DISCOVERY OF CANDIDATE GENES FOR STALLION FERTILITY FROM THE HORSE Y CHROMOSOME A Dissertation by NANDINA PARIA Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terje Raudsepp Committee Members, Bhanu P. Chowdhary William J. Murphy Paul B. Samollow Dickson D. Varner Head of Department, Evelyn Tiffany-Castiglioni August 2009 Major Subject: Biomedical Sciences iii ABSTRACT Discovery of Candidate Genes for Stallion Fertility from the Horse Y Chromosome. (August 2009) Nandina Paria, B.S., University of Calcutta; M.S., University of Calcutta Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terje Raudsepp The genetic component of mammalian male fertility is complex and involves thousands of genes. The majority of these genes are distributed on autosomes and the X chromosome, while a small number are located on the Y chromosome. Human and mouse studies demonstrate that the most critical Y-linked male fertility genes are present in multiple copies, show testis-specific expression and are different between species. In the equine industry, where stallions are selected according to pedigrees and athletic abilities but not for reproductive performance, reduced fertility of many breeding stallions is a recognized problem. Therefore, the aim of the present research was to acquire comprehensive information about the organization of the horse Y chromosome (ECAY), identify Y-linked genes and investigate potential candidate genes regulating stallion fertility. -

Genes in a Refined Smith-Magenis Syndrome Critical Deletion Interval on Chromosome 17P11.2 and the Syntenic Region of the Mouse

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Article Genes in a Refined Smith-Magenis Syndrome Critical Deletion Interval on Chromosome 17p11.2 and the Syntenic Region of the Mouse Weimin Bi,1,6 Jiong Yan,1,6 Paweł Stankiewicz,1 Sung-Sup Park,1,7 Katherina Walz,1 Cornelius F. Boerkoel,1 Lorraine Potocki,1,3 Lisa G. Shaffer,1 Koen Devriendt,4 Małgorzata J.M. Nowaczyk,5 Ken Inoue,1 and James R. Lupski1,2,3,8 Departments of 1Molecular & Human Genetics, 2Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, 3Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas 77030, USA; 4Centre for Human Genetics, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Catholic University of Leuven, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium; 5Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4J9, Canada Smith-Magenis syndrome (SMS) is a multiple congenital anomaly/mental retardation syndrome associated with behavioral abnormalities and sleep disturbance. Most patients have the same ∼4 Mb interstitial genomic deletion within chromosome 17p11.2. To investigate the molecular bases of the SMS phenotype, we constructed BAC/PAC contigs covering the SMS common deletion interval and its syntenic region on mouse chromosome 11. Comparative genome analysis reveals the absence of all three ∼200-kb SMS-REP low-copy repeats in the mouse and indicates that the evolution of SMS-REPs was accompanied by transposition of adjacent genes. Physical and genetic map comparisons in humans reveal reduced recombination in both sexes. Moreover, by examining the deleted regions in SMS patients with unusual-sized deletions, we refined the minimal Smith-Magenis critical region (SMCR) to an ∼1.1-Mb genomic interval that is syntenic to an ∼1.0-Mb region in the mouse. -

Menkes Disease Submitted By: Alice Ho, Jean Mah, Robin Casey, Penney Gaul

Neuroimaging Highlight Editors: William Hu, Mark Hudon, Richard Farb “From Sheep to Babe” – Menkes Disease Submitted by: Alice Ho, Jean Mah, Robin Casey, Penney Gaul Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2003; 30: 358-360 A four-month-old boy presented with a new onset focal On examination, his length (66 cm) and head circumference seizure lasting 18 minutes. During the seizure, his head and eyes (43 cm) were at the 50th percentile, and his weight (6.6 kg) was were deviated to the left, and he assumed a fencing posture to the at the 75th percentile. He had short bristly pale hair, and a left with pursing of his lips. He had been unwell for one week, cherubic appearance with full cheeks. His skin was velvety and with episodes of poor feeding, during which he would become lax. He was hypotonic with significant head lag and slip-through unresponsive, limp and stare for a few seconds. Developmentally on vertical suspension. His cranial nerves were intact. He moved he was delayed. He was not yet rolling, and he had only just all limbs equally well with normal strength. His deep tendon begun to lift his head in prone position. He could grasp but was reflexes were 3+ at patellar and brachioradialis, and 2+ not reaching or bringing his hands together at the midline. He elsewhere. Plantar responses were upgoing. was cooing but not laughing. His past medical history was Laboratory investigations showed increased lactate (7.7 significant for term delivery with fetal distress and meconium mmol/L) and alkaline phosphatase (505 U/L), with normal CBC, staining. -

Menkes Disease: Report of Two Cases

Iran J Pediatr Case Report Dec 2007; Vol 17 ( No 3), Pp:388-392 Menkes Disease: Report of Two Cases Mohammad Barzegar*1, MD; Afshin Fayyazie1, MD; Bobollah Gasemie2, MD; Mohammad ali Mohajel Shoja3, MD 1. Pediatric Neurologist, Department of Pediatrics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, IR Iran 2. Pathologist, Department of Pathology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, IR Iran 3. General Physician, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, IR Iran Received: 14/05/07; Revised: 20/08/07; Accepted: 10/10/07 Abstract Introduction: Menkes disease is a rare X-linked recessive disorder of copper metabolism. It is characterized by progressive cerebral degeneration with psychomotor deterioration, hypothermia, seizures and characteristic facial appearance with hair abnormalities. Case Presentation: We report on two cases of classical Menkes disease with typical history, (progressive psychomotor deterioration and seizures}, clinical manifestations (cherubic appearance, with brittle, scattered and hypopigmented scalp hairs), and progression. Light microscopic examination of the hair demonstrated the pili torti pattern. The low serum copper content and ceruloplasmin confirmed the diagnosis. Conclusion: Menkes disease is an under-diagnosed entity, being familiar with its manifestation and maintaining high index of suspicion are necessary for early diagnosis. Key Words: Menkes disease, Copper metabolism, Epilepsy, Pili torti, Cerebral degeneration Introduction colorless. Examination under microscope reveals Menkes disease (MD), also referred to as kinky a variety of abnormalities, most often pili torti hair disease, trichopoliodystrophy, and steely hair (twisted hair), monilethrix (varying diameter of disease, is a rare X-linked recessive disorder of hair shafts) and trichorrhexis nodosa (fractures of copper metabolism.[1,2] It is characterized by the hair shaft at regular intervals)[4].