Chapter 2: a City of Two Nations, West and East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

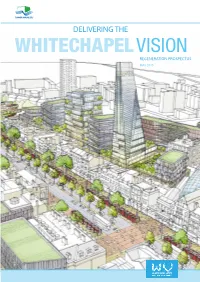

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-Branding East London's Digital Economy

Title Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/14511/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma (2018) Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 19 (2). pp. 409-432. ISSN 1468-2710 Cr e a to rs Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author FORTHCOMING IN JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London's digital economy Max Nathan1, Emma Vandore2 and Georgina Voss3 1 University of Birmingham. Corresponding author 2 Kagisha Ltd 3 London College of Communication Corresponding author details: Birmingham Business School, University House, University of Birmingham, BY15 2TY. [email protected] Abstract We explore place branding as an economic development strategy for technology clusters, using London’s ‘Tech City’ initiative as a case study. We site place branding in a larger family of policies that develop spatial imaginaries, and specify affordances and constraints on place brands and brand-led strategies. Using mixed methods over a long timeframe, we analyse Tech City’s emergence and the overlapping, competing narratives that preceded and succeeded it, highlighting day-to-day challenges and more basic tensions. While a strong brand has developed, we cast doubt on claims that policy has had a catalytic effect, at least in the ways originally intended. -

Cloud Study CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Bermondsey Square, London, SE1 3UN 3 October 2017 – 30 March 2018 Monday 2 October, Press Launch 5 – 6Pm; Public Launch 6 – 8Pm

Press Release SCULPTURE AT LAUNCHES NEW COMMISSION BY CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Charlie Godet Thomas, Cloud Study sketch, 2017 Cloud Study CHARLIE GODET THOMAS Bermondsey Square, London, SE1 3UN 3 October 2017 – 30 March 2018 Monday 2 October, Press launch 5 – 6pm; Public launch 6 – 8pm VITRINE is delighted to announce that British artist Charlie Godet Thomas will create the second commission for its 2017 – 2018 SCULPTURE AT programme. Entitled Cloud Study, Godet Thomas’ sculpture, which will be unveiled in Bermondsey Square on 2 October 2017, uses the form of a weather vane to represent states of emotional well-being. A speech bubble sits atop a two-metre high vane, which turns in the wind revealing the phrase ‘- yo’ is stuck in thar fo’ever li’l gray cloud.!’ that has been laser cut into the steel shape so as to be visible from both sides. The line comes from the widely syndicated American cartoon ‘Li’l Abner’ created by Al Cap that ran between 1934 – 1977. In the comic strip, one of its characters, Joe Btfsplk, entombs the cloud that bedevils him in a cave, sealing it with a boulder. Similar to the myth of the ostrich burying its head in the sand, the protection this offers is, of course, illusory. A playfully metaphorical work that embraces the personal and political, Cloud Study invites the viewer to meditate on the tragi-comic nature of life, with the movement of the vane mirroring these oscillations as it twists and turns in the wind. Says Charlie Godet Thomas: ‘In Cloud Study, I hope to evade what I see as the traditional hallmarks of public sculpture: for an imposing quality to be substituted by quietness, heroism by the everyday, stillness by function, sternness by humour, and vulnerability in the place of grandstanding.’ Says Director of VITRINE and SCULPTURE AT Alys Williams: ‘SCULPTURE AT was founded with the aim of creating an experimental platform for artists to make work in the public realm; a platform to include artists without previous public sculpture experience. -

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004 East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities The final version of this paper was published in the Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp 528 545 (2005) Abstract Twice in the recent history of the East End of London, the fight for decent housing has become part of a bigger political battle. These two very different struggles are representative of two important periods in radical politics – the class politics, tempered by popularfrontism that operated in the 1930s, and the new social movement politics of the seventies. In the rent strikes of the 1930s the ultimate goal was Communism. Although the local Party was disproportionately Jewish, Communist theory required an outward looking orientation that embraced the whole of the working class. In the squatting movement of the 1970s political organisers attempted to steer the Bengalis onto the path of Black Radicalism, championing separate organisation and turning the community inwards. An examination of the implementation and consequences of these different movements can help us to understand the possibilities and problems for the transformation of grassroots activism into a broader political force, and the processes of political mobilisation of ethnic minority groups. Key Words Tower Hamlets, political mobilisation, oral history, Bengalis, Jews, housing In London’s East End, housing crises are endemic. The fight for adequate and decent housing is fundamental, but for most of those taking part its goals do not extend beyond the satisfaction of housing needs. -

Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: a Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb

REVIEW ESSAY How Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens are rewriting the maritime history of East London North of the Thames: a review Derek Morris, Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: A Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb. 1st ed, 2002; 2nd ed., The East London History Society, 2007; a new edition in process to be extended back in time to cover from 1660; Derek Morris and Ken Cozens, Wapping, 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Maritime Suburb. The East London History Society, 2009; Derek Morris, Whitechapel 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Inner Suburb. The East London History Society, 2011; £12.60 and £3:50 p&p (overseas $18.50), http://wwww.eastlondonhistory .org.uk In three books published to date, two London-based researchers, Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens, have set about the task of challenging many deeply-held stereotypes of London’s eastern parishes in the eighteenth century. With meticulous attention to detail, and with sure control of a wide range of archives, they have produced three highly-recommended works. The books Mile End and Wapping are in very short supply, if not by the time of this review, only available on the second-hand market. In Whitechapel, with the completion of the first phase of their research, they have ignored the restrictions imposed by parish boundaries: they have begun to draw conclusions about the nature of society in these areas in the eighteenth century. This is welcome for a number of reasons. But chief among these is that for too long historians have relied on a series of stereotypes with the emphasis on poverty, crime and “dirty industries,” to portray these eastern parishes, when in fact the emphasis should be on the important role played by local entrepreneurs in London’s growing economy and worldwide trading networks. -

East End Newspaper Reports

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 169 Title: East End Newspaper Reports Scope: Notes, transcripts and xerox copies of reports relating to Jewish immigration from a range of London East End newspapers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Dates: 1880-1910 Level: Fonds Extent: 20 boxes (28 files) Name of creator: Joseph John Bennett Administrative / biographical history: From the early 1880s, as a consequence of violent anti-semitism in some countries of Eastern Europe such as Russia and Bulgaria, the immigration of Jews into Britain assumed politically significant dimensions, and brought with it hostility and antagonism within some sections of the host population. The East End of London, in areas like Whitechapel, was the main focus of such immigration. East End newspapers of the period carried many reports of related incidents and opinions. In 1905 the Aliens Act, intended to restrict ‘pauper’ and ‘undesirable’ aliens was passed. The material in this collection of notes, transcripts and newspaper reports was compiled by Joseph John Bennett during research in pursuance of the degree of M.Phil. (1979) at the University of Sheffield (thesis entitled East End newspaper opinion and Jewish immigration, 1885-1905). Related collections: Zaidman Papers Source: Presented to the University Library by the author on completion of his research. System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Antisemitism - Great Britain; Jews in Great Britain; England - Emigration and immigration Names: Bennett, John Joseph; London - East End Conditions of access: Academic researchers by appointment Restrictions: No restrictions Copyright: Copyright of the author’s work remains with the author; newspaper reports are covered by Copyright legislation Finding aids: There is a finding list of the files, the newspapers used and their dates, but no detailed index. -

What Light Rail Can Do for Cities

WHAT LIGHT RAIL CAN DO FOR CITIES A Review of the Evidence Final Report: Appendices January 2005 Prepared for: Prepared by: Steer Davies Gleave 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD [t] +44 (0)20 7919 8500 [i] www.steerdaviesgleave.com Passenger Transport Executive Group Wellington House 40-50 Wellington Street Leeds LS1 2DE What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence Contents Page APPENDICES A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK B Overseas Experience C People Interviewed During the Study D Full Bibliography P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence APPENDIX A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence A1. TYNE & WEAR METRO A1.1 The Tyne and Wear Metro was the first modern light rail scheme opened in the UK, coming into service between 1980 and 1984. At a cost of £284 million, the scheme comprised the connection of former suburban rail alignments with new railway construction in tunnel under central Newcastle and over the Tyne. Further extensions to the system were opened to Newcastle Airport in 1991 and to Sunderland, sharing 14 km of existing Network Rail track, in March 2002. -

124-126 the Grove Stratford London E15 1Ns

MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 124-126 THE GROVE STRATFORD LONDON E15 1NS FREEHOLD MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY LOCATED IN THE HEART OF STRATFORD Queen Elizabeth Here East Olympic Park Business Park Lee Valley Velopark City of London Westfield Stratford City Shopping Cente Birbeck University of London Stratford Shopping Centre SUBJECT PROPERTY INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS ■ Freehold mixed-use development opportunity located in the heart of Stratford ■ Sold with vacant possession ■ The existing building totals approximately 242 sq m (2,605 sq ft) and comprises a three ■ Stratford shopping centre is within a short walking distance storey former bank at ground floor with office and ancillary uppers ■ Stratford Station (Central Line) is within 0.64 km (0.4 miles) and Maryland (TfL Rail) is ■ Two planning consents granted (C3 and C1 uses) for demolition of the existing three within 0.48 km (0.3 miles) of the property storey building and redevelopment of a six storey mixed-use development to provide retail accommodation at ground floor level and nine flats above (1 x one bed, 6 x two ■ Offers invited in excess of £1,700,000 for the Freehold interest, subject to contract and bed, 2 x three bed) exclusive of VAT ■ 100% private scheme 124-126 THE GROVE Stratford, London, E15 1NS LOCATION The property is situated in East London, in the centre of Stratford, within the London Borough of Newham. The property is located on the western side of The Grove, close to its junctions with Broadway to the south and Great SUBJECT Eastern Road (A118) to the north. PROPERTY The surrounding area comprises an abundance of local amenities with Stratford Shopping Centre to the rear of the property and Westfield Stratford City 0.80 km (0.5 miles) west of the property. -

Loyola University New Orleans Study Abroad

For further information contact: University of East London International Office Tel: +44 (0)20 8223 3333 Email: [email protected] Visit: uel.ac.uk/international Docklands Campus University Way London E16 2RD uel.ac.uk/international Study Abroad uel.ac.uk/international Contents Page 1 Contents Page 2 – 3 Welcome Page 4 – 5 Life in London Page 6 – 9 Docklands Campus Page 10 – 11 Docklands Page 12 – 15 Stratford Campus Page 16 – 17 Stratford Page 18 – 19 London Map Page 20 – 21 Life at UEL Page 23 Study Abroad Options Page 25 – 27 Academic School Profiles Page 28 – 29 Practicalities Page 30 – 31 Accommodation Page 32 Module Choices ©2011 University of East London Welcome This is an exciting time for UEL, and especially for our students. With 2012 on the horizon there is an unprecedented buzz about East London. Alongside a major regeneration programme for the region, UEL has also been transformed. Our £170 million campus development programme has brought a range of new facilities, from 24/7 multimedia libraries and state-of-the-art clinics,to purpose-built student accommodation and, for 2011, a major new sports complex. That is why I am passionate about our potential to deliver outstanding opportunities to all of our students. Opportunities for learning, for achieving, and for building the basis for your future career success. With our unique location, our record of excellence in teaching and research, the dynamism and diversity provided by our multinational student community and our outstanding graduate employment record, UEL is a university with energy and vision. I hope you’ll like what you see in this guide and that you will want to become part of our thriving community. -

Transforming East London Together

TRANSFORMING EAST LONDON TOGETHER 2013 - 2023 Stansted London’s business community relies on international connectivity to trade successfully in the inter- Luton connected global economy. East London is fortunate to be well-served by an international airport that has “ been at the heart of the economic regeneration and rejuvenation of the area since 1987. The existence of London City has been a catalyst for business investment in the area. With more start-up businesses than any other part of London and clusters emerging such as Tech City and the Royal Docks, the growth of the airport in line with increasing demand will be essential. Without the quick and convenient air links provided by London City, I am certain that many businesses would have chosen alternative locations. Southend London City Airport Colin Stanbridge, ” Chief Executive, London Chamber of Commerce and Industry Heathrow 10 Without doubt, London City Airport has played a major, and critical, role in ExCeL London’s development as a miles true International Convention Centre. The connectivity with Europe, and beyond, is a major asset, as it is with 20 “ all other London businesses, particularly those based in East London. Further future development of London miles City Airport is welcomed by us, and I would say is also critical in the continued regeneration of East London. 30 miles *distances approximate Kevin Murphy, ” Gatwick Chairman, ExCeL London Approximate travel times from London City Airport O2 Arena Canary Wharf Olympic Park The Shard Bank Waterloo Westminster DLR/Tube 10 mins 12 mins 14 mins 19 mins 22 mins 23 mins 25 mins 5 miles 10 miles 2 Source: Transport for London Journey Planner Introduction Since opening in 1987, London City Airport (LCY) has been central to the economic “ regeneration of East London.