The Isle of Dogs: Four Development Waves, Five Planning Models, Twelve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

London Borough of Croydon/Matter 51

London borough of Croydon/Matter 51 Matter 51: Delivering Social Infrastructure 1. This matter statement on delivering social infrastructure should be read in the context of the overall response by the London Borough of Croydon (ref 5622), in which the Council said that there is much to be welcomed and supported in the Draft London Plan. The Mayor’s Good Growth vision echoes Croydon Council’s own vision set out in the recently adopted Croydon Local Plan (February) 2018 (CLP18). The Council continues to work with the Mayor to enable and deliver his, and our own, vision for growth in the borough. All arguments and concerns regarding the Draft London Plan’s policies hinge from the Council’s original representation. 2. It should be noted that the Council are mainly commenting on the Draft London Plan as it relates to the specific delivery of housing and infrastructure, particularly in Croydon, outer London and the suburbs. Question; Delivering Social Infrastructure M51. Would Policy S1 provide an effective and justified approach to the development of London’s social infrastructure? In particular would it be effective in meeting the objectives of policies GG1 and GG3 in creating a healthy city and building strong and inclusive communities? In particular: a) Would Policy S1, in requiring a needs assessment of social infrastructure and encouraging cross borough collaboration provide an effective and justified strategic framework for the preparation of local plans and neighbourhood plans in relation to the development of social infrastructure? -

Cinnabar Wharf Central, 24 Wapping High Street, London, E1w 1Nq

CINNABAR WHARF CENTRAL, 24 WAPPING HIGH STREET, LONDON, E1W 1NQ Furnished, £1,250 per week + £276 inc VAT one off admin and other charges may apply.* Available Now FLAT 60 CINNABAR WHARF CENTRAL, 24 £1,250 per week Furnished reception room • kitchen • 3 bedrooms • 3 bathrooms • balcony with views of the River Thames • parking • 24hr porterage • administrative EPC Rating = charges D apply Council Tax = H Description A well appointed 3 bedroom apartment in this prestigious development close to St. Katharine’s Dock and Tower Hill. The apartment benefits from a river facing wrap around balcony, higher tiered mezzanine which offer views over Tower Bridge. The property further benefits from private parking and 24hr security. The City, Canary Wharf and West End are conveniently accessed via Wapping and Tower Hill underground stations. Energy Performance A copy of the full Energy Performance Certificate is available on request. Viewing Strictly by appointment with Savills. FLOORPLANS Gross internal area: 0 sq ft, m² Gross external area: FILL IN *Admin fees including drawing up the tenancy agreement, reference charge for one tenant – £276 inc VAT. £36 inc VAT for each additional tenant, occupant, guarantor reference where required. Inventory check-out fee – charged at end of tenancy. Third party charge dependant on property size and whether furnished/unfurnished/part furnished and the company available at the time. Deposit – usually equivalent to 6 weeks rent, though may be greater subject to mutual agreement. Pets – additional Savills Wapping deposit required generally equivalent to two weeks rent. For more details, visit savills.co.uk/fees. Kristina Dabrila Important notice: Savills, their clients and any joint agents give notice that: 1: They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, [email protected] either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. -

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript Date: Monday, 24 October 2016 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 October 2016 From Sail to Steam: London’s Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Elliott Wragg Introduction The almost deserted River Thames of today, plied by pleasure boats and river buses is a far cry from its recent past when London was the greatest port in the world. Today only the remaining docks, largely used as mooring for domestic vessels or for dinghy sailing, give any hint as to this illustrious mercantile heritage. This story, however, is fairly well known. What is less well known is London’s role as a shipbuilder While we instinctively think of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Clyde as the homes of the Royal Navy, London played at least an equal part as any of these right up until the latter half of the 19th century, and for one brief period was undoubtedly the world’s leading shipbuilder with technological capability and capacity beyond all its rivals. Little physical evidence of these vast enterprises is visible behind the river wall but when the tide goes out the Thames foreshore gives us glimpses of just how much nautical activity took place along its banks. From the remains of abandoned small craft at Brentford and Isleworth to unique hulked vessels at Tripcockness, from long abandoned slipways at Millwall and Deptford to ship-breaking assemblages at Charlton, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey, these tantalising remains are all that are left to remind us of London’s central role in Britain’s maritime story. -

LEATHAMS, 227-255 ILDERTON ROAD South Bermondsey, London SE15 1NS

LEATHAMS, 227-255 ILDERTON ROAD South Bermondsey, London SE15 1NS Landmark Consented Mixed Use Development Opportunity View of consented scheme from Sharratt Street (Source: Maccreanor Lavington) Leathams, 227-255 Ilderton Road Southwark, London SE15 1NS 2 OPPORTUNITY SUMMARY DESCRIPTION • Landmark mixed use development The site is broadly rectangular in shape and extends to approximately 0.39 hectares (0.96) acres. It is currently occupied by opportunity in South Bermondsey within a three storey industrial warehouse (use class B1 and B8) and used as an industrial food storage and distribution centre (B8) with ancillary office space (B1). The internal area extends to approximately 2,529 sqm (27,222 sq ft) GIA and the two external London Borough of Southwark. loading yards extend to approximately 874 sqm (9,408 sq ft). • 0.39 hectare (0.96) acre site. The table below sets out the existing area schedule: • Existing site comprises an industrial EXISTING INDUSTRIAL SPACE GIA (SQM) GIA (SQ FT) warehouse building with two loading yards Storage (B8) 2,005 21,582 extending to approximately 3,403 (sqm) Ancillary Offices (B1) 523 5,630 36,630 sq ft GIA occupied by Leathams Total Workspace 2,529 27,222 Food Distribution business. Covered loading yard 730 7,858 • Located 800 metres (0.5 miles) south External Plant 144 1,550 of South Bermondsey Overground Total Site Area 3,403 36,630 station, providing regular services to Source: Design & Access Statement Maccreanor Lavington London Bridge (5 minutes), and the wider Underground Network (Northern Line and Jubilee line). • New Bermondsey Overground station scheduled for completion in 2025 located 400 metres to the east of site. -

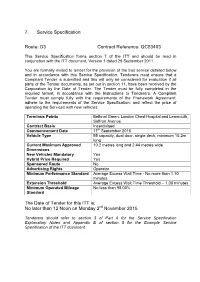

D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 the Date of Tender for This ITT Is

7. Service Specification Route: D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Bethnal Green, London Chest Hospital and Leamouth, Saffron Avenue Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 17th September 2016 Vehicle Type 55 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 10.2m long Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.44 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold – 1.00 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard The Date of Tender for this ITT is: nd No later than 12 Noon on Monday 2 November 2015 Tenderers should refer to section 3 of Part A for the Service Specification Explanatory Notes and Appendix B of section 5 for the Example Service Specification of the ITT document. -

Shoreditch E1 01–02 the Building

168 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. SHOREDITCH E1 01–02 THE BUILDING 168 Shoreditch High Street offers up to 35,819 sq ft of contemporary workspace over six floors in Shoreditch’s most sought after location. High quality architectural materials are used throughout, including linear handmade bricks and black powder coated windows. Whilst the top two floors use curtain walling with black vertical fins – altogether a dramatic first impression for visitors on arrival. The interior is designed with dynamic businesses in mind – providing a stunning, light environment in which to work and create. STELLAR WORK SPACE 03–04 SHOREDITCH Shoreditch is still the undisputed home of the creative and tech industries – but has in recent years attracted other business sectors who crave the vibrant local environment, diverse amenity offering and entrepreneurial spirit. ORIGINALS ARTISTS VISIONARIES HOXTON Crondall St. d. Rd R st nd . Ea la s ng Ki xton St Ho . 05–06 SHOREDITCH Columbia Rd St Hoxton Sq. Rd 6 y d. R Pitfield ckne t s Ha Ea k Pl. Brunswic City 5 R d. 5 Cu St. d r Ol ta Calv et Ave i . 4 n Rivington Rd. Rd WALK TIMES . Arnold Circus. 3 11 OLD ST. 8 8 4 3 6 5 12 SHOREDITCH HIGH ST. STATION 7 MINS Shor 03 9 Gr 168 edit Leonard St. eat 1 10 1 E New Yard Inn. ch High . aste 4 6 7 11 2 Rd 2 10 h St. OLD SPITALFIELD MARKET . 2 churc een t rn 3 Red 4 MINS . 1 9 S St 9 07 8 . -

Limehouse, Westferry & Canary Wharf

LIMEHOUSE, WESTFERRY & CANARY WHARF RESIDENTS' INFORMATION SUNDAY 1 MARCH 2020 5 Road closures from 07:00 to 12:30 on Vehicle Crossing Point Sunday 1 March 2020 Three Colt Street Closed for runners from 08:55 to 11:15 The information provided in this leaflet is supplementary to The Vitality Big Half Road The vehicle crossing point will be open Closure Information booklet. Please make from 07:00 to 08:55. It will then close to sure you have read the booklet, which allow runners to pass and is anticipated to is available at thebighalf.co.uk/road- reopen at 11:15. closures Access to Three Colt Street is available Roads in Limehouse, Westferry and Canary from Commercial Road throughout the Wharf will close at 07:00 and reopen at 12:30 day. Additionally, an exit route via Grenade on Sunday 1 March. A vehicle crossing point Street to West India Dock Road north will operate during the times stated and will towards Commercial Road and Burdett close to traffic in advance of the runners. Road is available during the road closure The event will start by Ensign Street at the period. junction of The Highway, before travelling east along The Highway and through the Canary Wharf Limehouse Link Tunnel, Aspen Way and into Access is available to Canada Square car Canary Wharf. park from Preston's Road roundabout and Trafalgar Way from 7:00 to 08:30. Runners will then return via Westferry Road, Limehouse Causeway and Narrow Street Isle of Dogs where they will rejoin The Highway and Access and exit is available via Preston's continue through Wapping towards Road. -

Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-Branding East London's Digital Economy

Title Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/14511/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma (2018) Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London’s digital economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 19 (2). pp. 409-432. ISSN 1468-2710 Cr e a to rs Voss, Georgina and Nathan, Max and Vandore, Emma Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author FORTHCOMING IN JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY Spatial Imaginaries and Tech Cities: Place-branding East London's digital economy Max Nathan1, Emma Vandore2 and Georgina Voss3 1 University of Birmingham. Corresponding author 2 Kagisha Ltd 3 London College of Communication Corresponding author details: Birmingham Business School, University House, University of Birmingham, BY15 2TY. [email protected] Abstract We explore place branding as an economic development strategy for technology clusters, using London’s ‘Tech City’ initiative as a case study. We site place branding in a larger family of policies that develop spatial imaginaries, and specify affordances and constraints on place brands and brand-led strategies. Using mixed methods over a long timeframe, we analyse Tech City’s emergence and the overlapping, competing narratives that preceded and succeeded it, highlighting day-to-day challenges and more basic tensions. While a strong brand has developed, we cast doubt on claims that policy has had a catalytic effect, at least in the ways originally intended. -

Invest in Three Waters Bow Creek, E3

INVEST IN THREE WATERS BOW CREEK, E3. % 4PREDICTED RENT GROWTH IN LONDON THIS YEAR.1 1 Independent, 2019 INVESTOR CONFIDENCE HEADS EAST Buoyed by price growth, rental yield and government and business confidence, East London regeneration is at the heart of London’s fastest growing area.1 STRATFORD Over half of the Capital’s population now lives east of £800 /SQ FT* Tower Bridge. Hackney The region has become a beacon for City workers, creatives and entrepreneurs, all demanding SHOREDITCH competitively-priced homes with rapid journey times. Bow £1,325 This makes for strong capital growth prospects and /SQ FT* LONDON E3 gives confidence to buy-to-let investors, as these Bethnal Green CREEK BOW professionals demand high quality rental properties. ~ PROJECTED PRICE GROWTH2 LONDON Stepney House price performance in the Lower Lea Valley compared. Indexed 100 = September 2008. ~ E3 180 LOWER LEA VALLEY WHITECHAPEL NEWHAM The City £738 160 /SQ FT* TOWER HAMLETS £950 Poplar 140 /SQ FT* Shadwell 120 100 St Katharine & Wapping 2011 2017 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2010 2018 2009 2008 CANARY WHARF Borough 2 £1,250 PROJECTED POPULATION GROWTH 2018 – 2028 /SQ FT* Rotherhithe East London’s boroughs are catching the wave of population and demand growth that helps cement price growth. TOWER NEWHAM HACKNEY KENSINGTON CITY OF HAMLETS AND CHELSEA LONDON 12.8% 11.3% 10.6 % 4.5 % 2.7% 3 1 Dataloft Land Registry increase in Inner London regeneration developments 2012–2016 * Based on average property prices 2 Knight Frank Research / GLA INVESTOR CONFIDENCE HEADS EAST Buoyed by price growth, rental yield and government and business confidence, East London regeneration is at the heart of London’s fastest growing area.1 STRATFORD Over half of the Capital’s population now lives east of £8,610 /SQ M* Tower Bridge. -

THOMSON REUTERS MAP.Ai

PUBLIC TRANSPORT PUBLIC TRANSPORT Watford M Hatfield A1 2 LIMEHOUSE DOCKLAND 1 M25 1 DLR 1 N TRAIN STATION LIGHT RAILWAY M Hendon A1 27 Situated on Commercial Road Canary Wharf Station. Situated High A406 (A13), walk to the Limehouse at the centre of North and South Wycombe Basildon The Thomson Reuters Building M 2 DLR Station and catch a Colonnade. The Station is a two M4 5 South Colonnade 0 A40 A1 3 connecting train to Canary minute walk from our building. A1 3 Slough Canary Wharf Wharf. CITY OF • London C ity LONDON Airport London M4 Tilbury LONDON CITY LONDON UNDERGROUND • A20 5 2 E14 5ep CANARY WHARF • AIRPORT Heathrow A205 M Airport Jubilee Line Extention – links Catch a connecting London Gravesend A3 Croydon Canary Wharf with Waterloo City Airport shuttle bus to SECTION M 2 +44 (0)20 7250 1122 0 Station and London Bridge, Canary Wharf DETAILED M3 BELOW M25 thomsonreuters.com also other tube lines. Wok ing Limehouse MANOR Train Station A Docklands B BURDETT 1 ROAD 1 0 A1 206 2 ROAD Blackwell Tunnel 2 Isle of Dogs 1 Dover A1 02 N C anary Wharf WESTFERRY C IRC US (A1 3) Folkestone COMMERCIAL Royal Docks ROAD C ity 3 C anary A1 Wharf Airport C . London A1 3 One Way COMMERCIAL EAST INDIA ROAD C abot Square DOCK ROAD A1 3 L I M E H O U S E P P C anary Wharf Start here DLR A1 3 A1 3 From the East To Tower Gateway A L L (A1 3) & Central London 6 S A I N T S 0 2 1 P O P L A R Start here W E S T F E R R Y A C .