Poverty, Wealth and History in the East End of London : Life and Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

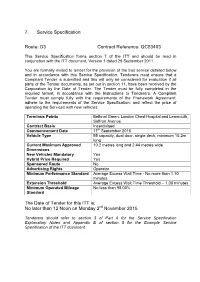

D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 the Date of Tender for This ITT Is

7. Service Specification Route: D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Bethnal Green, London Chest Hospital and Leamouth, Saffron Avenue Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 17th September 2016 Vehicle Type 55 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 10.2m long Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.44 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold – 1.00 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard The Date of Tender for this ITT is: nd No later than 12 Noon on Monday 2 November 2015 Tenderers should refer to section 3 of Part A for the Service Specification Explanatory Notes and Appendix B of section 5 for the Example Service Specification of the ITT document. -

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004

East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing Sarah Glynn 2004 East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities The final version of this paper was published in the Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp 528 545 (2005) Abstract Twice in the recent history of the East End of London, the fight for decent housing has become part of a bigger political battle. These two very different struggles are representative of two important periods in radical politics – the class politics, tempered by popularfrontism that operated in the 1930s, and the new social movement politics of the seventies. In the rent strikes of the 1930s the ultimate goal was Communism. Although the local Party was disproportionately Jewish, Communist theory required an outward looking orientation that embraced the whole of the working class. In the squatting movement of the 1970s political organisers attempted to steer the Bengalis onto the path of Black Radicalism, championing separate organisation and turning the community inwards. An examination of the implementation and consequences of these different movements can help us to understand the possibilities and problems for the transformation of grassroots activism into a broader political force, and the processes of political mobilisation of ethnic minority groups. Key Words Tower Hamlets, political mobilisation, oral history, Bengalis, Jews, housing In London’s East End, housing crises are endemic. The fight for adequate and decent housing is fundamental, but for most of those taking part its goals do not extend beyond the satisfaction of housing needs. -

East End Newspaper Reports

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 169 Title: East End Newspaper Reports Scope: Notes, transcripts and xerox copies of reports relating to Jewish immigration from a range of London East End newspapers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Dates: 1880-1910 Level: Fonds Extent: 20 boxes (28 files) Name of creator: Joseph John Bennett Administrative / biographical history: From the early 1880s, as a consequence of violent anti-semitism in some countries of Eastern Europe such as Russia and Bulgaria, the immigration of Jews into Britain assumed politically significant dimensions, and brought with it hostility and antagonism within some sections of the host population. The East End of London, in areas like Whitechapel, was the main focus of such immigration. East End newspapers of the period carried many reports of related incidents and opinions. In 1905 the Aliens Act, intended to restrict ‘pauper’ and ‘undesirable’ aliens was passed. The material in this collection of notes, transcripts and newspaper reports was compiled by Joseph John Bennett during research in pursuance of the degree of M.Phil. (1979) at the University of Sheffield (thesis entitled East End newspaper opinion and Jewish immigration, 1885-1905). Related collections: Zaidman Papers Source: Presented to the University Library by the author on completion of his research. System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Antisemitism - Great Britain; Jews in Great Britain; England - Emigration and immigration Names: Bennett, John Joseph; London - East End Conditions of access: Academic researchers by appointment Restrictions: No restrictions Copyright: Copyright of the author’s work remains with the author; newspaper reports are covered by Copyright legislation Finding aids: There is a finding list of the files, the newspapers used and their dates, but no detailed index. -

Discover Old Ford Lock & Bow Wharf

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park Victoria River Lee Navigation Bonner Hall Well Street G Park Islington Hackney Bridge Common r Camden o v Green e Victoria Park R l o a a n Skew Deer Park Pavilion a d Café C Bridge n io n Re U ge n West Lake rd t’s o f C Chinese rt an He Discover al Pagoda d Se oa Grove Road Old Ford Lock w R e a c Bridge rd rd a st o l & Bow Wharf o F P ne d r R Ol to Old Ford Lock & oa ic d V Royal Bow Wharf recall Old Ford Lock Wennington London’s grimy Road industrial past. Now Bethnal Green being regenerated, Wennington it remains a great Green place to spot historic Little adventures Bow Mile End d canal features. o a Ecology on your doorstep Wharf R an Park o m STAY SAFE: R Stay Away From Mile End the Edge Mile End & Three Mills Map not to scale: covers approx 0.5 miles/0.8km Limehouse River Thames A little bit of history Old Ford Lock is where the Regent’s Canal meets the Hertford Union Canal. The lock and Bow Wharf are reminders of how these canals were once a link in the chain between the Port of London and the north. Today, regeneration means this area is a great place for family walks, bike rides and for spotting wildlife. Best of all it’s FREE!* ive things to d F o at O ld Fo rd Lo ck & Bow Wharf Information Spot old canal buildings converted to new uses and Bow Wharf canal boats moored along the canal. -

Bethnal Green Walk

WWW.TOWERHAMLETS.GOV.UK 8 THE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FOR TOWER HAMLETS PRODUCED BY YOUR COUNCIL This month Graham Barker takes a springtime stroll through the historic parks and streets of Bethnal Green and beyond. Photos by Mike Askew. Set off with a spring in your step SPRING can be an inspiring time to Continue through Ion Square Gardens, get out and about, with flowers, glimpsing Columbia Road as you reach green shoots, buds and blossom Hackney Road. breaking through. This walking You now detour briefly out of the bor- route takes in some East End high- ough. To the left of Hackney City Farm (8) lights including parks, canals, histo- enter Haggerston Park, once the Imperial ry and art. Gas Works. Tuilerie Street alongside marks We start this month’s walk at Bethnal the French tile makers who had kilns here. Green Tube station. St John’s Church (1) At the tennis courts, join the Woodland towers above you, with its elegant win- Walk as it skirts initially by the farm and dows and golden weather vane. It was then left uphill and around the BMX track. designed in 1825 by Bank of England archi- On reaching Goldsmith’s Row, turn left – tect Sir John Soane and holds a command- beware of enthusiastic cyclists – cross to ing position. the Albion pub and continue on over the Cross at the lights in front of the church, Regent’s Canal hump-backed bridge. and there, behind Paradise Gardens, sits Ahead is Broadway Market (9), full of inter- Paradise Row, cobbled and narrow. -

The Manufacture of Matches

Life and Work: Poverty, Wealth and History in the East End of London Part One: The East End in Time and Space Time: The Historical Life of the East End Resource Spitalfields By Sydney Maddocks From: The Copartnership Herald, December 1931-January 1932 With the exception of its inhabitants and of those who have business there to attract them, Spitalfields is but little known even to a large number of the population of East London, whose acquaintance with it is often confined only to an occasional journey in a tramcar along Commercial Street, the corridor leading from Whitechapel to Shoreditch. By them the choice of the site of the church, as well as that of the market, may very easily be attributed to the importance of the thoroughfare in which they are both now found; but such is not the case, for until the middle of the last century Commercial Street had not been cut through the district. The principal approach to Spitalfields had previously been from Norton Folgate by Union Street, which, after a widening, was referred to in 1808 as "a very excellent modern improvement." About fifty years ago this street was renamed Brushfield Street, after Mr. Richard Brushfield, a gentleman prominent in the conduct of local affairs. The neighbourhood has undergone many changes during the last few years owing to rebuilding and to the extension of the market, but the modern aspect of the locality is not, on this occasion, under review, for the references which here follow concern its past, and relate to the manner of its early constitution. -

East London History Society Speakers for Our Lecture Programme Are Always Welcomed

T 6sta 0 NEWSLETTER oniort Volume 3 Issue 05 January 2010 0 c I 11A4 Uggeo {WI .41 ea. 1414...... r..4 I.M. minnghtep 111. `.wry caag, hew. Nor., +.11 lc, 2/10 .11,..4e...1..1 lo: tn... F..... mad. I.4.. xis Mock 14.1Ing 1934: The largest salmon ever sold in Billingsgate Fish Market, weighing in at 74Ibs. This beauty came from Norway and sold for 2/10 a pound when typical prices were 2/3. Louis Forman stands behind the salmon wearing a black Hombcrg hat. CONTENTS: Editorial Note Memorial Research 2 Book Etc 8 Programme Details Olympic Site Update 3 Bethnal Green Tube Disaster 9 Tower Hamlets Archives 4 East End Photographers 7 — James Pitt 12 St Georges Lutheran Church Talks 5 Missionaries in Bow 14 Correspondence 6 Strange Death from Chloroform 15 Notes and News 7 Spring Coach Trip 2010 16 ELHS Newsletter January 2010 Editorial Note: MEMORIAL RESEARCH I The Committee members are as follows: Philip Mernick, Chairman, Doreen Kendall, On the second Sunday of every month Secretary, Harold Mernick, Membership, members of our Society can be found David Behr, Programme, Ann Sansom, recording memorials in Tower Hamlets Doreen Osborne, Howard Isenberg and Cemetery known locally as Bow Cemetery. Rosemary Taylor. Every memorial gives clues to the family interred such as relationships and careers. All queries regarding membership should be addressed to Harold Mernick, 42 Campbell With modern technology it is possible to call Road, Bow, London E3 4DT. up at the L.M.A. all leading newspapers till 1900. It gives us a great feeling when we Enquiries to Doreen Kendall, 20 Puteaux discover another clue to the hidden history of House, Cranbrook Estate, Bethnal Green, the cemetery. -

Buses from Shadwell from Buses

Buses from Shadwell 339 Cathall Leytonstone High Road Road Grove Green Road Leytonstone OLD FORD Stratford The yellow tinted area includes every East Village 135 Old Street D3 Hackney Queen Elizabeth Moorfields Eye Hospital bus stop up to about one-and-a-half London Chest Hospital Fish Island Wick Olympic Park Stratford City Bus Station miles from Shadwell. Main stops are for Stratford shown in the white area outside. Route finder Old Ford Road Tredegar Road Old Street BETHNAL GREEN Peel Grove STRATFORD Day buses Roman Road Old Ford Road Ford Road N15 Bethnal Green Road Bethnal Green Road York Hall continues to Bus route Towards Bus stops Great Eastern Street Pollard Row Wilmot Street Bethnal Green Roman Road Romford Ravey Street Grove Road Vallance Road 115 15 Blackwall _ Weavers Fields Grove Road East Ham St Barnabas Church White Horse Great Eastern Street Trafalgar Square ^ Curtain Road Grove Road Arbery Road 100 Elephant & Castle [ c Vallance Road East Ham Fakruddin Street Grove Road Newham Town Hall Shoreditch High Street Lichfield Road 115 Aldgate ^ MILE END EAST HAM East Ham _ Mile End Bishopsgate Upton Park Primrose Street Vallance Road Mile End Road Boleyn 135 Crossharbour _ Old Montague Street Regents Canal Liverpool Street Harford Street Old Street ^ Wormwood Street Liverpool Street Bishopsgate Ernest Street Plaistow Greengate 339 Leytonstone ] ` a Royal London Hospital Harford Street Bishopsgate for Whitechapel Dongola Road N551 Camomile Street 115 Aldgate East Bethnal Green Z [ d Dukes Place continues to D3 Whitechapel Canning -

The Jubilee Greenway. Section 3 of 10

Transport for London. The Jubilee Greenway. Section 3 of 10. Camden Lock to Victoria Park. Section start: Camden Lock. Nearest stations Camden Town , Camden Road . to start: Section finish: Victoria Park - Canal Gate. Nearest stations Cambridge Heath or Bethnal Green . to finish: Section distance: 4.7 miles (7.6 kilometres). Introduction. Section three is a satisfying stretch along the Regent's Canal, from famous Camden Lock to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. This section highlights the contrasts of a living, growing capital, meandering between old districts and new developments, each with their own unique style and atmosphere. This section of the route takes the walker through Camden Town, Islington, Hackney and Bethnal Green, leading finally to Victoria Park. This provides a fascinating look at how London is changing; passing many new developments and constructions, while savouring the atmosphere of the canal. In some ways the towpath side has changed little, whereas the south side of the canal has developed a great deal. For walkers interested in the history of London's canals you will pass near the London Canal Museum on this section. Look out for the Jubilee Greenway discs in the pavement as you go round. Continues below Directions. To start section three from section two, continue along the towpath past Camden Lock Market. Cyclists have to dismount through the market area here. Coming from Camden Town station, turn left, cross over the road and the bridge to find the towpath on the north side of the canal. Once on the canal towpath, pass rows of Vespa Scooters used as cafe seats and a large bronze lion, as well as many food stalls. -

Bethnal Green Ward Profile

Bethnal Green Ward Profile Corporate Research Unit May 2014 Page 1 Contents Population ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Ethnicity .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Religion ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Housing ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Health - Limiting illness or disability ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Unpaid care provision ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Labour market participation ........................................................................................................................................................................................................