The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas. Rex Oliver Mooney Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mooney, Rex Oliver, "Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2484. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2484 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Pharmacies Expand Vaccine Role CVS, Walgreens to Start with 40K Doses a Week by Leonard Sparks

Reader-Supported News for Philipstown and Beacon Love IS IN THE Air Page 14 FEBRUARY 12, 2021 Celebrating 10 Years! Support us at highlandscurrent.org/join Pharmacies Expand Vaccine Role CVS, Walgreens to start with 40K doses a week By Leonard Sparks he federal COVID-19 vaccination effort is expanding to CVS and T Walgreens stores and grocery-based pharmacies, as many residents, especially seniors over 65, face futility in trying to book appointments. CVS began administering 20,600 vaccine doses in New York today (Feb. 12) at 32 locations outside New York City under the Federal Retail Pharmacy Program. The program will initially send 1 million doses of the Moderna vaccine directly to 6,500 pharmacies nationwide each week, bolster- ing what each state is already distributing to pharmacies. Walgreens also began administering doses today under the program, allocating 18,600 doses to 187 of its pharmacies in New York City and 10,700 doses to 107 stores in the rest of the state. Retail Business Services LLC, which operates pharmacies at five East Coast grocery store chains, including Stop & Shop and Hannaford, is also vaccinating STORM SENTRY — As the snow kept falling, the farmers at the Glynwood Center for Regional Food and Farming in Philipstown at some of its New York locations. had to ensure the animals were safe and fed and that their tunnel homes didn’t collapse under the weight of the snow. This shot Under state guidelines, hospitals are prior- was taken last week during the first storm. “Pigs are naturally playful and curious and ours do seem to enjoy rooting around in itizing their vaccines for health care workers the snow,” said Liz Corio of Glynwood. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: W, Th 1:30-3 by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 11-12:15 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 3.120 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (8th Edition). Reading packet: available on Blackboard. COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

Inaugural History

INAUGURAL HISTORY Here is some inaugural trivia, followed by a short description of each inauguration since George Washington. Ceremony o First outdoor ceremony: George Washington, 1789, balcony, Federal Hall, New York City. George Washington is the only U.S. President to have been inaugurated in two different cities, New York City in April 1789, and his second took place in Philadelphia in March 1793. o First president to take oath on January 20th: Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1937, his second inaugural. o Presidents who used two Bibles at their inauguration: Harry Truman, 1949, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953, George Bush, 1989. o Someone forgot the Bible for FDR's first inauguration in 1933. A policeman offered his. o 36 of the 53 U.S. Inaugurations were held on the East Portico of the Capitol. In 1981, Ronald Reagan was the first to hold an inauguration on the West Front. Platform o First platform constructed for an inauguration: Martin Van Buren, 1837 [note: James Monroe, 1817, was inaugurated in a temporary portico outside Congress Hall because the Capitol had been burned down by the British in the War of 1812]. o First canopied platform: Abraham Lincoln, 1861. Broadcasting o First ceremony to be reported by telegraph: James Polk, 1845. o First ceremony to be photographed: James Buchanan, 1857. o First motion picture of ceremony: William McKinley, 1897. o First electronically-amplified speech: Warren Harding, 1921. o First radio broadcast: Calvin Coolidge, 1925. o First recorded on talking newsreel: Herbert Hoover, 1929. o First television coverage: Harry Truman, 1949. [Only 172,000 households had television sets.] o First live Internet broadcast: Bill Clinton, 1997. -

Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince Nancy Pittman Pinchot Guilford, Connecticut

Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince Nancy Pittman Pinchot Guilford, Connecticut A rebel is the kind of person who feels his rebellion not as a plea for this or that reform, but as an unbearable tension in his viscera. [He has] to break down the cause of his frustration or jump out of his skin. -Walter Lippmann' Introduction Amos Richards Eno Pinchot, if remembered at all, is usually thought of only as the younger, some might say lesser, brother of Gifford Pinchot, who founded the Forest Service and then became two-time governor of Pennsylva- nia. Yet Amos Pinchot, who never held an important position either in or out of government and was almost always on the losing side, was at the center of most of the great progressive fights of the first half of this century. His life and Amos and GirdPinchot Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince career encompassed two distinct progressive eras, anchored by the two Roosevelt presidencies, during which these ideals achieved their greatest gains. During the twenty years in between, many more battles were lost than won, creating a discouraging climate. Nevertheless, as a progressive thinker, Amos Pinchot held onto his ideals tenaciously. Along with many others, he helped to form an ideological bridge which safeguarded many of the ideas that might have perished altogether in the hostile climate of the '20s. Pinchot seemed to thrive on adversity. Already out of step by 1914, he considered himself a liberal of the Jeffersonian stamp, dedicated to the fight against monopoly. In this, he was opposed to Teddy Roosevelt, who, was cap- tivated by Herbert Croly's "New Nationalism," extolled big business controlled by even bigger government. -

Extensions of Remarks E189 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

February 10, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E189 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS EXTENDING COUNTERTERRORISM Whereas, this remarkable and tenacious have the right to pass its own laws and spend AUTHORITIES man of God and this phenomenal and virtuous its own local-taxpayer raised funds without Proverbs 31 woman have given hope to the congressional interference. SPEECH OF hopeless, fed the hungry and are beacons of I am certain most of you would resist federal HON. BETTY McCOLLUM light to those in need, they both have been interference in the local affairs of your cities blessed with two wonderful children, Ronald and counties. Whether it involves matters of OF MINNESOTA Ramsey, II and Christyn Ramsey both of health, safety or the education of children in IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES whom are honor students that are now enjoy- your Districts—these are decisions best left to Tuesday, February 8, 2011 ing college life; and the people who must live or die with their Ms. MCCOLLUM. Mr. Speaker, I firmly be- Whereas, Ronald and Doris Ramsey are choices. lieve that we can fight terrorism and keep our distinguished citizens of our district, they are Who are we in this body to ram our beliefs communities safe without sacrificing the rights spiritual warriors, persons of compassion, fear- and ideology down the throats of others? I un- and liberties that generations of Americans less leaders and servants to all, but most of all derstand why my colleague Congresswoman have fought so hard to secure. H.R. 514 fails visionaries who have shared not only with ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON and the people of this critical test, and I will vote to oppose it. -

TENDING TOWARD the UNTAMED: ARTISTS RESPOND to the WILD GARDEN Wave Hill Glyndor Gallery, April 3–August 19, 2012

Images Available Upon Request Contact: Martha Gellens 718.549.3200 x232 or [email protected] TENDING TOWARD THE UNTAMED: ARTISTS RESPOND TO THE WILD GARDEN Wave Hill Glyndor Gallery, April 3–August 19, 2012 Bronx, NY, February 14, 2012– Wave Hill’s signature Wild Garden serves as an inspiration for eight artists who are creating new work in a variety of media, including painting, animation, photography, sculpture and new media installation in Glyndor Gallery. The artists are particularly interested in the garden’s display of species from around the world, as well as in the tension between the Wild Garden’s seemingly untamed appearance and the intensive activity required to create and maintain it. Works by Isabella Kirkland and Anat Shiftan portray the remarkable variety of plants represented in the Wild Garden, while Julie Evans and Rebecca Morales embrace its diverse plant palette and mix of spontaneity and control. Gary Carsley, Chris Doyle and Erik Sanner capture the stimulating experience of viewing the garden’s varied and immersive terrain; Janelle Lynch shares their interest in the cycles of change represented by the growth, continual maintenance and decomposition of the Wild Garden’s plants over the seasons. Based on concepts championed by Irish gardener William Robinson in the 1870’s, the Wild Garden achieves a relaxed, serendipitous quality that contrasts with more formal parts of Wave Hill’s landscape. Wave Hill horticultural staff have undertaken a transformation of the Wild Garden in the last year, rejuvenating flower beds, opening new vistas to the Hudson River and Palisades and improving pathways, all with an eye to restoring the balance between the amount of light experienced in this part of the garden and the feeling of enclosure that is characteristic of this garden ―room.‖ The Wild Garden provides a framework for the new art created for this spring’s exhibition. -

Djvu Document

----F-------------------------------------------------------- !lvert~d. May God ~ve to you ~isdom and courage m thts hour of destiny. God still lives and rules in the affairs of men and nations." A reply came by return mail, signed by the President himself: THE WHITE HOUSE December 7, 1950 Dear Mr. Dick: Your message of December fourth is a source of encouragement and strength to me. Please tell your associates that I am deeply grateful for their kind thought in sustaining me through their prayers for Divine Guidance. Very truly yours, • A Call to Prayer [Signed] Harry Truman. God can change the most hopeless situ AS WE go to press, an urgent call to ation into a victory for His cause. "He £1 prayer is being sounded throughout doeth according to his will in the army of our ranks the world around. The heaven, and among the inhabitants of the world situation is grave. The shadow of earth." Dan. 4:35. what some feel might be a third world war Ezekiel and Daniel lived at a time of falls across the nations. Mankind is cring· widespread distress and bloodshed. In their ing in fear. "A third world war will mean day the sun <?f Assyrian power had just set, the suicide of the race," declares one states· and_ Babyloman tyranny was spreading des man. He voices the apprehension of many. olation everywhere. Ezekiel's soul was dis If men ever needed divine guidance, they tressed. "He mourned bitterly day and need it now. night." But God gave him the assurance How many times in national and inter that He was still in control. -

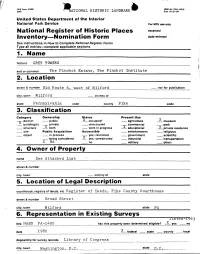

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

MRS Form 10-900 OMB No 1024-OO18 (3-32 i ATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic GREY TOWERS ' and or common The Pinchot Estate, The Pinchot Institute 2. Location street & number Old Route 6, west Of Milford not for publication city, town Milford vicinity of state Pennsylvania code county Pike code 3. Classification Category Ownership Staltus Present Use V y district __ public X occupied- __ agriculture museum building(s) _ private unoccupied commercial 'park Structure both work in oroaress "• educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X NA no military other: 4. Owner of Property name See Attached List street & number city, town ___ vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Register of Deeds, Pike County Courthouse street & number Broad Street city, town Milford state PA 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title HABS PA-1400 has this property been determined eligible? yes no date I960 federal state county local depository for survey records Library of Congress city, town Washington,__D^_C.__ state p.p.. NPS Form 10-900-I OMB No 1024-0018 C3-82) tip W-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Inventory—Nomination Form Continuation sheet Item number Page LOCAL ELECTED OFFICIALS Township of Milford James Snyder Chairman of the Board of Supervisors 4-03 W. -

Parts; Among the Tomatoes, Picking Grapes in the ^ G He, Gave the Nation'while Riding

light and at night y o u ^ tiW u e e d an owl's optics to read. them,. W# understand that when the hdnor About rowii Heard A lopg^Main Street roll was ordered it was underatootf lighting would be provided. We, haven’t tried to read the honor roll 8uru#t Council, Degree of Ppea- Mtitvehester's Side Streetn^ T oo at night and the complahjt we honUi, iwin meet *t thc^ heard came from a war jworker clubhouse Monday evening. The] ^itrr.s a_ e stands In 'vfor what bad been done, by some who doesn’t happen ,lo be in the Charles Henry Sturtevant; trcas> election of officers to serve for the. one hlghsi lip. A few days ^ter- vicinity of the Center during day H p l o D ia s Presented to urer,„Jean.Bridget Brennan. next six months v.ill be held. an-J; the varlotfs m *^ cl« are^the bane ‘ of uie^lerks, and the plckets^^ ward the same customer came In light hours. Address to Class , List of Oradnataa a njemorial service will follow for to the store. He dug down among Following are the graduates : deceased members. hwisers are Ju.st as bad, we afe-. .^told. In one local store . a cus- The .^grapee,' hauling out, first one Our attention was called the j 1 by Rev. McLeab; Joan Therasa Bennebi, kRay» buncJt'ajnd tlien another. ITlnally, othier day to a Negro truck driver ; mon Armand Berthiauma, xJeatt^^i *Qlaek Hawk^ Division Atnves h t Children Of Mary Sodality oT S t.: tomers was particularly J*oo»>'- . -

The Brandeis Gambit: the Making of America's "First Freedom," 1909-1931

William & Mary Law Review Volume 40 (1998-1999) Issue 2 Article 7 February 1999 The Brandeis Gambit: The Making of America's "First Freedom," 1909-1931 Bradley C. Bobertz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Bradley C. Bobertz, The Brandeis Gambit: The Making of America's "First Freedom," 1909-1931, 40 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 557 (1999), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol40/iss2/7 Copyright c 1999 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE BRANDEIS GAMBIT: THE MAKING OF AMERICA'S "FIRST FREEDOM," 1909-1931 BRADLEY C. BOBERTZ* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................. 557 I. FREE SPEECH AND SOCIAL CONFLICT: 1909-1917 ..... 566 II. WAR AND PROPAGANDA ......................... 576 III. JUSTICE HOLMES, NINETEEN NINETEEN ............ 587 IV. THE MAKING OF AMERICA'S "FIRST FREEDOM. ....... 607 A. Free Speech as Safety Valve ................ 609 B. Bolshevism, Fascism, and the Crisis of American Democracy ...................... 614 C. Reining in the Margins .................... 618 D. Free Speech and Propagandain the "Marketplace of Ideas"..................... 628 V. THE BRANDEIS GAMBIT ........................ 631 EPILOGUE: SAN DIEGO FREE SPEECH FIGHT REVISITED .... 649 INTRODUCTION A little after two o'clock on the sixth afternoon of 1941, Frank- lin Roosevelt stood at the clerk's desk of the U.S. House of Rep- resentatives waiting for the applause to end before delivering one of the most difficult State of the Union Addresses of his * Assistant Professor of Law, University of Nebraska College of Law.