Section 8.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: W, Th 1:30-3 by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 11-12:15 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 3.120 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (8th Edition). Reading packet: available on Blackboard. COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive

“A Progressive Conservative”: The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive Party Campaign of 1912 A thesis submitted by Marena Cole in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Tufts University May 2017 Adviser: Reed Ueda Abstract The election of 1912 was a contest between four parties. Among them was the Progressive Party, a movement begun by former president Theodore Roosevelt. George Perkins and Frank Munsey, two wealthy businessmen with interests in business policy and reform, provided the bulk of the Progressive Party’s funding and proved crucial to its operations. This stirred up considerable controversy, particularly amongst the party’s radical wing. One Progressive, Amos Pinchot, would later say that the two corrupted and destroyed the movement. While Pinchot’s charge is too severe, particularly given the support Perkins and Munsey had from Roosevelt, the two did push the Progressive Party to adopt a softer program on antitrust regulation and enforcement of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Progressive Party’s official position on antitrust and the Sherman Act, as shaped by Munsey and Perkins, would cause internal ideological schisms within the party that would ultimately contribute to the party’s dissolution. ii Acknowledgements This thesis finalizes my time at the Tufts University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, which has been a tremendously challenging and fulfilling place to study. I would first like to thank those faculty at Boston College who helped me find my way to Tufts. I have tremendous gratitude to Lori Harrison-Kahan, who patiently guided me through my first experiences with archival research. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

Extensions of Remarks E189 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

February 10, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E189 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS EXTENDING COUNTERTERRORISM Whereas, this remarkable and tenacious have the right to pass its own laws and spend AUTHORITIES man of God and this phenomenal and virtuous its own local-taxpayer raised funds without Proverbs 31 woman have given hope to the congressional interference. SPEECH OF hopeless, fed the hungry and are beacons of I am certain most of you would resist federal HON. BETTY McCOLLUM light to those in need, they both have been interference in the local affairs of your cities blessed with two wonderful children, Ronald and counties. Whether it involves matters of OF MINNESOTA Ramsey, II and Christyn Ramsey both of health, safety or the education of children in IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES whom are honor students that are now enjoy- your Districts—these are decisions best left to Tuesday, February 8, 2011 ing college life; and the people who must live or die with their Ms. MCCOLLUM. Mr. Speaker, I firmly be- Whereas, Ronald and Doris Ramsey are choices. lieve that we can fight terrorism and keep our distinguished citizens of our district, they are Who are we in this body to ram our beliefs communities safe without sacrificing the rights spiritual warriors, persons of compassion, fear- and ideology down the throats of others? I un- and liberties that generations of Americans less leaders and servants to all, but most of all derstand why my colleague Congresswoman have fought so hard to secure. H.R. 514 fails visionaries who have shared not only with ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON and the people of this critical test, and I will vote to oppose it. -

Djvu Document

----F-------------------------------------------------------- !lvert~d. May God ~ve to you ~isdom and courage m thts hour of destiny. God still lives and rules in the affairs of men and nations." A reply came by return mail, signed by the President himself: THE WHITE HOUSE December 7, 1950 Dear Mr. Dick: Your message of December fourth is a source of encouragement and strength to me. Please tell your associates that I am deeply grateful for their kind thought in sustaining me through their prayers for Divine Guidance. Very truly yours, • A Call to Prayer [Signed] Harry Truman. God can change the most hopeless situ AS WE go to press, an urgent call to ation into a victory for His cause. "He £1 prayer is being sounded throughout doeth according to his will in the army of our ranks the world around. The heaven, and among the inhabitants of the world situation is grave. The shadow of earth." Dan. 4:35. what some feel might be a third world war Ezekiel and Daniel lived at a time of falls across the nations. Mankind is cring· widespread distress and bloodshed. In their ing in fear. "A third world war will mean day the sun <?f Assyrian power had just set, the suicide of the race," declares one states· and_ Babyloman tyranny was spreading des man. He voices the apprehension of many. olation everywhere. Ezekiel's soul was dis If men ever needed divine guidance, they tressed. "He mourned bitterly day and need it now. night." But God gave him the assurance How many times in national and inter that He was still in control. -

Parts; Among the Tomatoes, Picking Grapes in the ^ G He, Gave the Nation'while Riding

light and at night y o u ^ tiW u e e d an owl's optics to read. them,. W# understand that when the hdnor About rowii Heard A lopg^Main Street roll was ordered it was underatootf lighting would be provided. We, haven’t tried to read the honor roll 8uru#t Council, Degree of Ppea- Mtitvehester's Side Streetn^ T oo at night and the complahjt we honUi, iwin meet *t thc^ heard came from a war jworker clubhouse Monday evening. The] ^itrr.s a_ e stands In 'vfor what bad been done, by some who doesn’t happen ,lo be in the Charles Henry Sturtevant; trcas> election of officers to serve for the. one hlghsi lip. A few days ^ter- vicinity of the Center during day H p l o D ia s Presented to urer,„Jean.Bridget Brennan. next six months v.ill be held. an-J; the varlotfs m *^ cl« are^the bane ‘ of uie^lerks, and the plckets^^ ward the same customer came In light hours. Address to Class , List of Oradnataa a njemorial service will follow for to the store. He dug down among Following are the graduates : deceased members. hwisers are Ju.st as bad, we afe-. .^told. In one local store . a cus- The .^grapee,' hauling out, first one Our attention was called the j 1 by Rev. McLeab; Joan Therasa Bennebi, kRay» buncJt'ajnd tlien another. ITlnally, othier day to a Negro truck driver ; mon Armand Berthiauma, xJeatt^^i *Qlaek Hawk^ Division Atnves h t Children Of Mary Sodality oT S t.: tomers was particularly J*oo»>'- . -

J353F (07780)/ J395 (07920) HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES in JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall 2013

Historical Perspectives in journalism 1 J353F (07780)/ J395 (07920) HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES IN JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall 2013 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: Belo 3.328 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: 11-12 MW 12W, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time:10-11 MWF, CMA 6.170 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (8th Edition). Reading packet: available on Blackboard. COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J353F will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. Historical Perspectives in journalism 2 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Commemorating the 75Th Anniversary of the Strath- More Vanderbilt Country Club

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Strath- more Vanderbilt Country Club WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to recognize those special places within the Empire State which provide recreational oppor- tunity for residents and which have become a part of the history of our State; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long- standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to commem- orate the 75th Anniversary of the Strathmore Vanderbilt Country Club; and WHEREAS, In 1860, approximately 60 settlers were granted title to land in an area called Manhasset, New York; the rolling terrain, later to become Strathmore Vanderbilt, was part of the vast Spreckel's Estate belonging to a wealthy farmer in the sugar business; and WHEREAS, Records indicate that title was conveyed in 1906 to William Chester; he subdivided the property by selling it for use as country estate to people whose names appeared prominently on the society lists of New York City; this marked the beginning of an elegant period that featured weekend country leisure such as riding and entertaining, and the homes were well-staffed by domestic help from abroad; and WHEREAS, In 1914, William Chester sold the remaining part of his hold- ings, a French Chateau, to an ice cream and candy entrepreneur, Louis Sherry; he was enamored with the well-balanced architecture, and proceeded to redecorate the house to resemble the Petite Trianon, a cottage of Marie Antoinette at Versailles; and WHEREAS, The formal garden, -

Uij BK Km B: M M M .--I Captain Willard in This Big Movement

r '-- J"f T"y fi r"75" f" T5 """1 Yror ' -- ' s3sf?5 EDITORIAL PAGE WASHINGTON OF THE WASHINGTON TIMES APRIL 2. 1919 1 1- - The League of Husbands -- : By T. E. Powers That Scheme of Capt. Willard Should WtMmhin$&mw It Was a Cruel Blow. THE NATIONAL DAILY Receive Immediate Favorable Reg. V. S. Pale Office. i ARTHUR BRISBAXR. Hdltor and Owner Recommendation "P!Tf3Ar? r Tiihlllnr stav M'at-tungto- u. A Waterside Entcrcw iyscond class VcBtofflco at P. I Park for All the People oh the Reclaimed Laad matter at the Lets Put IVE VToVour. houseJ Published Every Evening Mnrludlnp Minaays oy W rT ' S Opposite the Navy Yard. The Washington Times Company, Munsey Bldg., Pennsylvania Aye, one over. Mb C , SCHEIE J, yV J o, Ma.ll 1 3 $1.95; 1 Month. Subscriptions: year (Inc. Sundays). $7.50; Months. on the ' v&& ' ?r ? 1 1 BY WEDNESDAY. APRIL . 1S19 league ' js. x&fys7 t -- irrnrrr-j-i EARL GODWIN. nC A I sA 'IS---' - 7 r. ' If There is not the slightest question about the merit of fi7 the plan of Capt. A. L. - "WILLABD, of the Navy Yard, who Roosevelt, Bonds, Storms- recommends that a great athletic and recreation field for 4 the public be established ! "What Interests One Man Bores Another on the reclaimed land across the river from the Navy Yard. is Theodore Roosevelt the Second, energetic son of an It a plan for the use of the PUBLIC'S own grounds by the PUBLIC in the finest possible way. energetic father, announces that he will leave the Wall Under this plan all of east "Washington would have the benefit of a play Street brokerage office in which he is employed to go into ground as fine as Potomac -- Park and there would be the politics. -

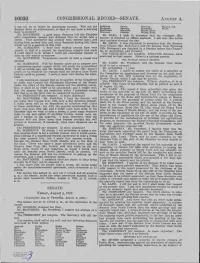

Congressional Record-Sen Ate. August 4

110932 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SEN ATE. AUGUST 4, I can not do so unless by unanimous consent. Will not the Robinson Smoot Sterling Watson, Ind. Sheppard Spencer Trammell Willis Senator move an adjournment, so that we can have a morning Shortridge Stanfield Walsh, Mass. hour to-morrow? J Simmons Stanley Walsh, Mont. M.r. McCUMBER. A good many Senators left the Chamber Mr. DIAL. I wish to announce that my colleague [Mr. after unanimous consent was obtained that. we would take a SMITH] is detained on official business. I ask that this notice recess. That agreement has already been entered into; and may continue through the day. having been entered into, and many Senators having left, there Mr. LADD. I was requested to announce that the Senator would not be a quorum at this time. from Illinois [Mr. McKINLEY] and the Senator from Wyoming 1\ir. HARRISON. I have been staying around here very [Mr. KENDRICK] are detained in a hearing before the Commit closely, so that if a request for unanimous c?nsent was made tee on Agriculture and Forestry. I could object to it~ unless I could get unarumous consent to The PRESIDENT pro tempore. Fifty-ei;ht Senators have take up this matter to-morrow. answered to their names. There is a quorum present. Mr. l\IcCUMBER. Unanimous consent to t.a.ke a recess was granted. THE MUSCLE SHOALS PROJECT. Mr. HARRISON. Will the Senator allow me to propose now l\Ir. LADD. Mr. President, will the Senator from Idaho a unanimous-consent request which will settle the proposition? yield to me a moment? I did so awhile ago., and the Senator from Utah [Mr. -

OLIVET Mfvicinity

¦—¦——— ——vgmmmm - T. i 1 ¦ . ... - worse than that,** says'the Anamosa ’ AReat-Ra” Lenaet Are Different. | UJUUiJUUiitcmtituu* a public Wale' Frb. Hit and arc gelling THE OSKALOOSA HERALD. Eureka. "It IS a severe reflection of ready to move to Minnesota. They the Inability of the legislature to sup- have proven themselves good citizens vbllahed Weekly on Tburedaya *t plant public sentiment with law.” ' and we are sorry to have them leuve Oekelooem, Ibhuki County, town. —— i - ¦¦ ——— the neighborhood. —Are we to infer that art is super- Not j PUBLIC SILIS j Godfrey, Hose and Augustine ship- 3EKALOOSA HERALD COMPANY. ior to the sciences by reason of the ped one load of butcher stuff from get mn m <tmintn rmu» here Tuesday Chicago. Sale $40,- Public fact that Frank Chance will for Pwbllshere.Publishers. Charles String 000 for managing the New York Amer- G. E. Reynolds W. A. Caldwell Spates and Frank A and fellow, Oskaloosa, came to Hose •stored at the Pootofflco nt Oska- icans, while Col. Goethals gets only will offer at public auction 4 miles of The undersigned will sell at Public Auction at his res- matter. $15,000 for digging the Panama canal? northeast Wright, on what is known Hill Wednesday morning on the fire- looea, town, an ¦econd-cUa* of fly was calling on idence 2\ miles north of Leighton, 9 miles south-east of as the Samuel Barkley farm, on Wed- and friends. into Frank Anderson unloaded a of Pella and nine miles north-west of Oskaloosa, on Mbaerlptlon—Two Dollar* Per Tear, —And now the goat is to come IHV Doctor nesday, Feb. -

George Perkins and the Progressive Party a Study of Divergent Goals

GEORGE PERKINS AND THE PROGRESSIVE PARTY A STUDY OF DIVERGENT GOALS APPROVED: L c (yj Major Professor Minor Professor rectot of Department Dehn of the Graduate School GFORGE PERKINS AND THE PROGRESSIVE PARTY A STUDY OF DIVERGENT GOALS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Pete W. Cobelle, B.S, Derston, Texas J armarv, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENDS Page PREFACE 1 Chapter 1. PRELUDE TO PARTY REVOLT 3 II. A PARTY IS BORN 30 III. PROGRESSIVE PARTY WARFARE 54 IV. THE FINAL YEARS 85 V. AFTERWARD .' 120 BIBLIOGRAPHY 129 ill GEORGE PERKINS A1JD THE PROGRESSIVE PARTY: A STUDY OF DIVERGKIT GOALS Preface In 1912 the Republican Party split and a new party, the Progressive Party, was forneci, There long has been an argu- ment as to whether the new party was a product of the times or of the needs of one man, Theodore Roosevelt. Regardless of the basis of the new party, it war. born and its first objective was to elect the "Bull Moose" presi- dent of the United States, Like any party the Progressives had to have money to operate. Two men, Frank Mnnsev and George Perkins, bore the brunt of the load. Whereas Munsey left the party after 1912, Perkins .remained and played a major role in the party's course in history. George W. Perkins, like nc-sfc Republican businessmen, had, in 1910, been prepared to re-elect President William Howard Taft in 1912. Despite President Taft's difficulties with the insurgents, Perkins' position regained much the sane throughout most of 1911.