The Development of Theodore Roosevelt's Attitude Toward Trusts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WSU 2Ü3l Century Art

WSU 2Ü3l Century Art •# WORKING AMERICA: INDUSTRIAL IMAGERY IN AMERICAN PRINTS, 1900-1940 22 March - 22 May 1983 First Floor American Wing Metropolitan Museum of Art Modern Art Library THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART The Library PRESENTED BY William S. Lieberman Smoking steel mills and factory assembly lines, skyscrapers and bridges under construction, pneumatic drill operators and arc welders are images that do not conform to the traditional subject matter of American art. Yet, by 1900, increasing urbanization and rapid industrial growth had become a vital part of American life and, correspondingly, of its art. Writers, dramatists, painters, photographers, and printmakers responded to these new stimuli. For printmakers, such as Joseph Pennell and B. J. 0. Nordfeldt, the billowing smoke from factories possessed a man-made beauty rivaling the best of nature. For others, the new buildings that pierced city skies inspired works recording a new group of cathedral builders scurrying about on catwalks far above city streets. By the outbreak of World War II industrial imagery was as viable a part of the American scene as pastoral pursuits. Artists, active in the various programs of the Works Progress Admin istration (WPA), were encouraged by the government to portray contemporary American life. The programs promoted arts for the people, whether murals in a post office or prints decorating a hospital ward. Bridge building, pipe-laying, and road construction, blast furnaces and mines were among the subjects explored by the printmakers associated with these programs. Some printmakers chose to examine the social issues of American industry, while others looked to the industrial landscape as the genesis for abstraction. -

Address by the Honorable Edward H. Levi, Attorney General of the United

ADDRESS BY THE HONORABLE EDWARD H. LEVI ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES AT THE DEDICATION CEREMONIES OF THE JOHN EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING 11:00 A.M. TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1975 J. EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING WASHINGTON, D. C. We have come together to dedicate this new building as the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It is a proper moment to look back to the tradition of this law enforcement organization as well as to look forward to t.he future it will meet in this new place. It was under Theodore Roosevelt that the predecessor of the FBI was founded. There was resistance to its creation. For varied reasons -- noble and base -- some feared the idea of a federal' criminal investigative agency within the Justice Department. But through'the persistence of Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte the organization was formed. The resistance did not crumble when Bonaparte's idea was accompli-shed. There were bad years to follow for the Bureau. It did not escape the tarnish of the Teapot Dome era. The Justice Department and the Bureau were criticized for failing to attack official corruption with sufficient vigor. From this period the' Bureau emerged with a new beginning under the man to whose memory this new building is dedicated. John Edgar Hoover was 29 years old when Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone appointed him acting director of the Bureau in May of 1924. Hoover's reputation of scrupulous honesty had been commended to Stone. Such a man was needed. Hoover set about reforming the Bureau to meet the demanding requirements of a more complicated era. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

1905-1906 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during: the Academical Year ending in JUNE, /9O6, INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY, HITHERTO UNREPORTED [Presented at the meeting of the Alumni, June 26, 1906] [No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical year ending in JUNE, 1906 Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [PRESENTED AT THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI, JUNE 26, 1906] I No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1831 JOSEPH SELDEN LORD, since the death of Professor Samuel Porter of the Class of 1829, m September, 1901, the oldest living graduate of^Yale University, and since the death of Bishop Clark m September, 1903, the last survivor of his class, was born in Lyme, Conn, April 26, 1808. His parents were Joseph Lord, who carried on a coasting trade near Lyme, and Phoebe (Burnham) Lord. He united with the Congregational church m his native place when 16 years old, and soon began his college preparation in the Academy of Monson, Mass., with the ministry m view. Commencement then occurred in September, and after his graduation from Yale College, he taught two years in an academy at Bristol, Conn He then entered the Yale Divinity School, was licensed to preach by the Middlesex Congregational Association of Connecticut in 1835, and completed his theological studies in 1836. After supplying 522 the Congregational church in -

THE PANAMA CANAL REVIEW November 2, 1956 Zonians by Thousands Will Go to Polls on Tuesday to Elect Civic Councilmen

if the Panama Canal Museum Vol. 7, No. 4 BALBOA HEIGHTS, CANAL ZONE, NOVEMBER 2, 1956 5 cents ANNIVERSARY PROGRAM TO BE HELD NOVEMBER 15 TO CELEBRATE FIFTIETH BIRTHDAY OF TITC TIVOLI Detailed plans are nearing completion for a community mid-centennial celebra- tion, to be held November 15, commem- orating the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the Tivoli Guest House. Arrangements for the celebration are in the hands of a committee headed by P. S. Thornton, General Manager of the Serv- ice Center Division, who was manager of the Tivoli for many years. As the plans stand at present, the cele- bration will take the form of a pageant to be staged in the great ballroom of the old hotel. Scenes of the pageant will de- pict outstanding events in the history of the building which received its first guests when President Theodore Roosevelt paid his unprecedented visit to the Isthmus November 14-17, 1906. Arrangements for the pageant and the music which will accompany it are being made by Victor, H. Herr and Donald E. Musselman, both from the faculty of Balboa High School. They are working with Mrs. C. S. McCormack, founder and first president cf the Isthmian Historical Society, who is providing them with the historical background for the pageant. Fred DeV. Sill, well-known retired em- ployee, is in charge of the speeches and introductions of the various incidents in HEADING THIS YEAR'S Community Chest Campaign are Lt. Gov. H. W. Schull, Jr., right, and the pageant. H. J. Chase, manager of the Arnold H. -

The Insular Cases: the Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid

ARTICLES THE INSULAR CASES: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGIME OF POLITICAL APARTHEID BY JUAN R. TORRUELLA* What's in a name?' TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 284 2. SETFING THE STAGE FOR THE INSULAR CASES ........................... 287 2.1. The Historical Context ......................................................... 287 2.2. The A cademic Debate ........................................................... 291 2.3. A Change of Venue: The Political Scenario......................... 296 3. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ............................................ 300 4. THE PROGENY OF THE INSULAR CASES ...................................... 312 4.1. The FurtherApplication of the IncorporationTheory .......... 312 4.2. The Extension of the IncorporationDoctrine: Balzac v. P orto R ico ............................................................................. 317 4.2.1. The Jones Act and the Grantingof U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Ricans ........................................... 317 4.2.2. Chief Justice Taft Enters the Scene ............................. 320 * Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. This article is based on remarks delivered at the University of Virginia School of Law Colloquium: American Colonialism: Citizenship, Membership, and the Insular Cases (Mar. 28, 2007) (recording available at http://www.law.virginia.edu/html/ news/2007.spr/insular.htm?type=feed). I would like to recognize the assistance of my law clerks, Kimberly Blizzard, Adam Brenneman, M6nica Folch, Tom Walsh, Kimberly Sdnchez, Anne Lee, Zaid Zaid, and James Bischoff, who provided research and editorial assistance. I would also like to recognize the editorial assistance and moral support of my wife, Judith Wirt, in this endeavor. 1 "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet." WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, ROMEO AND JULIET act 2, sc. 1 (Richard Hosley ed., Yale Univ. -

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Passing Through New Orleans There have been numerous times through the centuries that the phrase “passing through New Orleans” has been used. Sometimes the occasions and circumstances were happy, while some were frighteningly sad. Unwelcome visitors “passing through New Orleans” included the Aedes aegypti mosquito and the yellow fever deaths it brought. More than 41,000 victims died from the scourge of yellow jack in New Orleans between 1817 (the first year of reliable statistics) and 1905 (the Crescent City's last epidemic). Then there were all those hurricanes that, too, came uninvited. Who in the city can forget witnessing Hurricane Katrina passing through New Orleans on weather radar? But there was a multitude of welcome cargo, and the visitors that brought it alongside the city’s docks. President Thomas Jefferson could not understate the importance of this when he wrote, “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market.” By 1802, when Jefferson wrote those words, over one million dollars in American trade was floating down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to this great port city. This comprised two-thirds of the commerce “passing through New Orleans”. Flatboats came down the Mississippi filled with flour, beef, bacon, pork, Indian corn, oats, peas, beans, cotton, tobacco, lard, tallow, live-stock, poultry, wines, whiskey, cider, furs and hides, marble, feathers and lead. -

APUSH 3 Marking Period Plan of Study WEEK 1: PROGRESSIVISM

APUSH 3rd Marking Period Plan of Study Weekly Assignments: One pagers covering assigned reading from the text, reading quiz or essay covering week‘s topics WEEK 1: PROGRESSIVISM TIME LINE OF EVENTS: 1890 National Women Suffrage Association 1901 McKinley Assassinated T.R. becomes President Robert LaFollette, Gov. Wisconsin Tom Johnson, Mayor of Cleveland Tenement House Bill passed NY 1902 Newlands Act Anthracite Coal Strike 1903 Women‘s Trade Union founded Elkin‘s Act passed 1904 Northern Securities vs. U.S. Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty Roosevelt Corollary Lincoln Steffens, Shame of Cities 1905 Lochner vs. New York 1906 Upton Sinclair, The Jungle Hepburn Act Meat Inspection Act Pure Food and Drugs Act 1908 Muller vs. Oregon 1909 Croly publishes, The Promises of American Life NAACP founded 1910 Ballinger-Pinchot controversy Mann-Elkins Act 1912 Progressive Party founded by T. R. Woodrow Wilson elected president Department of Labor established 1913 Sixteenth Amendment ratified Seventeenth Amendment ratified Underwood Tariff 1914 Clayton Act legislated Federal Reserve Act Federal Trade Commission established LECTURE OBJECTIVES: This discussion will cover the main features of progressivism and the domestic policies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. It seeks to trace the triumph of democratic principles established in earlier history. A systematic attempt to evaluate progressive era will be made. I. Elements of Progressivism and Reform A. Paradoxes in progressivism 1. A more respectable ―populism‖ 2. Elements of conservatism B. Antecedents to progressivism 1. Populism 2. The Mugwumps 3. Socialism C. The Muckrakers 1. Ida Tarbell 2. Lincoln Stephens - Shame of the Cities 3. David Phillips - Treasure of the Senate 4. -

1908 Journal

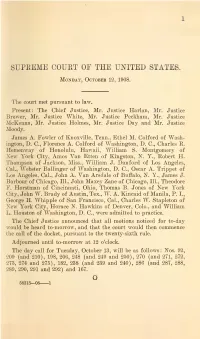

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: W, Th 1:30-3 by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 11-12:15 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 3.120 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (8th Edition). Reading packet: available on Blackboard. COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

Fine Americana Travel & Exploration with Ephemera & Manuscript Material

Sale 484 Thursday, July 19, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Americana Travel & Exploration With Ephemera & Manuscript Material Auction Preview Tuesday July 17, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, July 18, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, July 19, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material.