Special Issue on the African Union (AU), Published in the Year When Our Continental Union Is Celebrating Ten Years of Its Existence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Québec (Canada) 21 – 26 October 2012

127th Assembly of the 127ème Assemblée de Inter-Parliamentary Union and Related Meetings l’Union interparlementaire et réunions connexes Québec City, Canada Québec, Canada 21-26 October 2012 21-26 octobre 2012 www.ipu2012uip.ca Assembly A/127/4(a)-R.1 Item 4 14 September 2012 ENFORCING THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT: THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENT IN SAFEGUARDING CIVILIANS’ LIVES Draft report submitted by Mr. L. Ramatlakane (South Africa), co-Rapporteur Introduction The IPU, the global organization of parliaments, works for peace and cooperation among peoples and for the firm establishment of representative democracy;1 as such, it has identified Enforcing the responsibility to protect: the role of parliament in safeguarding civilians’ lives as a current issue of urgent concern. The "responsibility to protect" concept was endorsed by 191 countries in a resolution (A/RES/60/1) adopted at the United Nations World Summit in 2005. It refers to the responsibility of every State to safeguard its population from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. If a State fails to protect its citizens – meaning that it is no longer upholding its responsibility as a sovereign nation – and peaceful measures have failed, the international community has a responsibility to take corrective measures, with military action being the last resort. The concept’s proper and effective operationalization and implementation have often fallen short of the resolution adopted at the World Summit. This observation has been borne out by events in Egypt, Côte d’Ivoire and Libya, and the ambiguous responses to them. It is evident that parliaments – as assembled by a body such as the IPU – should express themselves on the issue. -

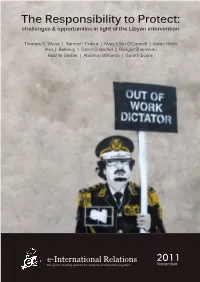

The Responsibility to Protect: Challenges & Opportunities in Light of the Libyan Intervention

The Responsibility to Protect: challenges & opportunities in light of the Libyan intervention Thomas G. Weiss | Ramesh Thakur | Mary Ellen O’Connell | Aidan Hehir Alex J. Bellamy | David Chandler | Rodger Shanahan Rachel Gerber | Abiodun Williams | Gareth Evans e-International Relations 2011 the world’s leading website for students of international politics November 1 Created in November 2007 by students from the UK universities Contents of Oxford, Leicester and Aberystwyth, e-International Relations (e-IR) is a hub of information and analysis on some of the key 4 Introduction issues in international politics. Alex Stark As well as editorials contributed by students, leading academics and policy-makers, the website contains essays, diverse 7 Whither R2P? perspectives on global news, lecture podcasts, blogs written by Thomas G. Weiss some of the world’s top professors and the very latest research news from academia, politics and international development. 12 R2P, Libya and International Politics as the Struggle for Competing Normative Architectures Ramesh Thakur 15 How to Lose a Revolution Mary Ellen O’Connell 18 The Illusion of Progress: Libya and the Future of R2P Aidan Hehir 20 R2P and the Problem of Regime Change Alex J. Bellamy 24 Libya: The End of Intervention David Chandler 26 R2P: Seeking Perfection in an Imperfect World Rodger Shanahan 28 Prevention: Core to R2P Rachel Gerber 31 R2P and Peacemaking Abiodun Williams Front page image by Joe Mariano 34 Interview: The R2P Balance Sheet After Libya Gareth Evans 2 3 Introduction Alex Stark | November 2011 he international community has a contentious The framework and scope of R2P was officially State to civil society members, that states have the perspectives has opened the floodgates to Thistory when it comes to preventing and codified at the 2005 UN World Summit. -

Responsibility to Protect: the Use and the Abuse

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Responsibility To Protect: The Use and The Abuse Marwan Hameed CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/544 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ! Responsibility to Protect: The Use and The Abuse Marwan Hameed May/2014 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at The City College of New York Advisor: Dr. Jean Krasno ! ! DEDICATION I dedicate this research to my people, the people of Iraq, who suffered and still suffering of being victims of armed conflicts that they did not choose, I also dedicate this work to all civilian around the world who got caught in middle of armed conflicts, and to my wife Noor who gave me the strength and backed me all the way to finish this thesis. ! 1! ! ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all I would like to give my special thanks and gratitude to my advisor Professor Jean Krasno for her tremendous support, guidance and patience through the writing of this paper. Without her support and guidance this paper would have never been completed the way it is now. I also would like to thank Michael Bush for being my second reader, and for his advise on how to concentrate on finishing my writing and reduce distraction came from too much reading. -

The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council: a Revolutionary Islamist Coalition in Libya by Kevin Truitte

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 5 The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council: A Revolutionary Islamist Coalition in Libya by Kevin Truitte Abstract The Derna Mujahideen Shura Council (DMSC) – later renamed the Derna Protection Force – was a coalition of Libyan revolutionary Islamist groups in the city of Derna in eastern Libya. Founded in a city with a long history of hardline Salafism and ties to the global jihadist movement, the DMSC represented an amalgamation of local conservative Islamism and revolutionary fervor after the 2011 Libyan Revolution. This article examines the group’s significant links to both other Libyan Islamists and to al-Qaeda, but also its ideology and activities to provide local security and advocacy of conservative governance in Derna and across Libya. This article further details how the DMSC warred with the more extremist Islamic State in Derna and with the anti-Islamist Libyan National Army, defeating the former in 2016 but ultimately being defeated by the latter in mid-2018. The DMSC exemplifies the complex local intersection between revolution, Islamist ideology, and jihadism in contemporary Libya. Keywords: Libya, Derna, Derna Mujahideen Shura Council, al-Qaeda, Islamic State Introduction The city of Derna has, for more than three decades, been a center of hardline Islamist jihadist dissent in eastern Libya. During the rule of Libya’s strongman Muammar Qaddafi, the city hosted members of the al-Qaeda- linked Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and subsequently served as their stronghold after reconciliation with the Qaddafi regime. The city sent dozens of jihadists to fight against the United States in Iraq during the 2000s. -

The Impact of Arab Spring Throughout the Middle East and North Africa

A MODEL OF REGIME CHANGE: THE IMPACT OF ARAB SPRING THROUGHOUT THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By OMAR KHALFAN BIZURU BA, Al Azhar University, Egypt, 1996 MA, Institute of Arab Research and Studies, Egypt, 1998 Ph.D. Nkumba University, Uganda, 2019 2021 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April 21st, 2021 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Omar Khalfan Bizuru ENTITLED A Model of Regime Change: The Impact of Arab Spring Throughout the Middle East and North Africa BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: _________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Department of History ___________________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Bizuru, Omar Khalfan, M.A., International and Comparative Politics Graduate Program, School of Public and International Affairs, Wright State University, 2021. A Model of Regime Change: The Impact of the Arab Spring Throughout the Middle East and North Africa. This study examined the catalysts for social movements around the globe; specifically, why and how the Arab Spring uprisings led to regime change in Tunisia, why they transformed into civil war in some countries of the Middle East and North Africa (Syria), and why they did not lead to significant change at all in other places (Bahrain). -

O Rigin Al a Rticle

International Journal of Political Science, Law and International Relations (IJPSLIR) ISSN (P): 2278-8832; ISSN (E): 2278-8840 Vol. 7, Issue 4, Aug 2017, 1-18 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. LIBYA: RELAPSE IN TO CRISIS AFTER MUAMMAR GADDAFI (SINCE 2011) ABEBE TIGIRE JALU Department of Philosophy, Dire Dawa University, Dire Dawa Institute of Technology (DDIT), Pre-Engineering, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia ABSTRACT The world saw a great revolution sparked in Tunisia, anchored in deep rooted political, economic and social factors as well as the emergence of social media networks, ultimately igniting the Arab Revolution of 2011. At the end of the year, three long tenured undemocratic rulers, Ben Ali, Hosni Mubarak, and Muammar Gaddafi were removed from power in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya respectively. In Libya, a full scale eight months of civil war, the intervention of the international community, the death of a dictator in the Libyan ‘February 17 Revolution’ of 2011, followed, unlike states in the region that have been in a similar pattern, by long lasting instability which is still unsolved. The UN has been following the case of Libya closely, since the outbreak and its attempt to mediate for peace among different factions in the post-revolution crisis was commendable in the midst of the problem of inclusiveness. Lack of inclusiveness in the establishment of the Government of National Accord in 2015/16 is boosting the current threat of Libya called ISIS/L. Those who were disappointed with the establishment of the government and power division are joining the terrorist Article Original groups. So, composition of the new governments should be reconsidered. -

Tribes and Revolution; the “Social Factor” in Muammar Gadhafi's

Tribes and Revolution; The “Social Factor” in Muammar Gadhafi’s Libya and Beyond Joshua Jet Friesen Department of Anthropology, McGill University June 2013 Thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Art in Anthropology © Joshua Friesen 2013 i Abstract: A revolt against Colonel Muammar Gadhafi’s Libyan government began in February of 2011. The conflict lasted for eight months and affected the entire country. Two distinct sides fought for control during those eight months making the conflict a civil war. This master’s thesis uses a series of interviews as well as the academic and journalistic literature produced about the Libyan conflict to argue that the war should also be understood as a revolution. Considering the war a revolution introduces a number of puzzles. Firstly, Colonel Gadhafi’s position within Libya was officially symbolic in much the same way Great Britain’s royalty is in Canada, yet Gadhafi was named as the revolution’s primary enemy. Secondly, Libya was officially a popular democracy with no executive administrative branches. A revolution against a political elite was therefore theoretically impossible. Nonetheless, the Libyans I interviewed considered Gadhafi more than the purely symbolic leader of Libya, and felt that Libya was actually closer to a dictatorship than a popular democracy. This thesis investigates the discrepancies between official and unofficial realities in Libya by exploring the role of society in the history of Colonel Gadhafi’s government. My analysis is focused by the question, “what role did tribes play in Libya’s revolution?” I argue that tribes provided a system for conceptually organizing Libya’s society during Colonel Gadhafi’s tenure. -

Armed Groups in Libya

Armed Groups in Libya: JUNE 2012 • Typology and Roles NUMBER 18 ight months after the death of Col. The emergence of armed groups Muammar Qaddafi, security in Libya is in Libya Econtested by an increasingly complex set of state and non-state armed actors. Nevertheless, The ‘17 February Revolution’ began in mid- available analysis on the situation in Libya February 2011 with mass protests in Benghazi tends to oversimplify what is an intricate and (see Map 1). Demonstrations quickly devolved fluid security environment. Some reports refer to into armed conflict in Benghazi, Misrata, and all non-state armed groups simply as ‘militias’ the Nafusa Mountains as Qaddafi’s forces (AI, 2012). Use of such terms risks obscuring cracked down on demonstrators (Al Jazeera, ARMED ARMED ACTORS critical differences among groups’ goals and 2011). The escalation of violence and the threat tactics (Small Arms Survey, 2006, p. 248). It can of heavy civilian casualties led the UN Security also misrepresent the multifaceted roles armed Council to pass resolution 1973 on 17 March groups play in post-conflict security environ- 2011, mandating member states and regional ments. Understanding and distinguishing organizations to ‘take all necessary measures’ to among the heterogeneous armed groups oper- protect civilians (UNSC, 2011, para. 4). France, ating in the country is thus critical for effective the UK, and the United States immediately international policy, especially as revolutionary enforced a no-fly zone and began military forces continue to view state security institu- strikes against Qaddafi ground forces that tions with suspicion. were threatening Benghazi (McGreal, 2011). This Research Note, based on a forthcoming NATO assumed responsibility for operations Small Arms Survey publication and extensive on 31 March 2011 (NATO, 2011). -

A Study on Libyans Living Abroad Profiling of Libyans Living Abroad to Develop a Roadmap for Strategic and Institutional Engagement

A STUDY ON LIBYANS LIVING ABROAD PROFILING OF LIBYANS LIVING ABROAD TO DEVELOP A ROADMAP FOR STRATEGIC AND INSTITUTIONAL ENGAGEMENT. A Study on Libyans Living Abroad International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) Gonzagagasse 1 1010 Vienna, Austria ICMPD Office in Tunisia Carthage Centre, Block A Rue du Lac de Constance Les Berges du Lac 1 1053 Tunis www.icmpd.org Written by: Martin Russell and Ramadan Sanoussi Belhaj ICMPD Team (in alphabetical order): Jihène Aissaoui, Brahim El Mouaatamid, Marcello Giordani, Emelie Glad, Sabiha Jouini-Marzouki, Theodora Korkas, Dr. Mohamed Kriaa Design and Layout: Moez Akkari Suggested Citation: ICMPD (2020), A Study on Libyans Living Abroad, Vienna: ICMPD. This publication was produced in the framework of the EU-funded project “Strategic and institutional management of migration in Libya”. © European Union, 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright owners. The information and views set out in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opi- nion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained there. NOTE FROM AUTHORS: All views expressed in this research are the views of the co-authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Centre for Migration Policy Development. The research remains independent in its findings and any errors/omissions in the research are the sole responsibility of the authors of the research. -

Libya and the Politics of the Responsibility to Protect Paper Presented at the OCIS Conference, Sydney University, July 18-20, 2012

Libya and the Politics of the Responsibility to Protect Paper Presented at the OCIS Conference, Sydney University, July 18-20, 2012 Jeremy Moses University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ***Draft version only – Please do not cite*** Abstract The Responsibility to Protect (RtoP) norm is usually framed in apolitical terms of civilian protection. This paper aims to challenge that depiction and demonstrate the deeply political nature of the RtoP, which is often elided or denied by its proponents. In order to achieve this, the paper will first look to the RtoP literature to demonstrate the depoliticisation of the norm, evident in the reference to the ‘international community’ or the ‘conscience of mankind’ as decisive factors in determining when the responsibility to protect has been breached and what should be done to rectify the situation. I will then turn to a case study of the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya. In this situation, the initial calls for intervention were premised upon the protection of civilian life against the murderous intent of the Gaddafi regime. The NATO action that followed the initial UN authorization, however, went far beyond the authority to protect civilians and strayed into the highly political realm of regime change, to the extent that the intervening forces became heavy participants in the forced displacement and massacre that occurred during the siege of Sirte. Taking sides, in this case, meant participating in violence against civilians of a similar nature to that which called forth the intervention in the first place. This example will be used to demonstrate the inevitable ‘fall’ into politics – and a profoundly ‘sovereign’ politics at that – that will accompany any physical attempt to protect civilians in the context of a civil war. -

From Sanctions to the Soleimani Strike to Escalation: Evalu- Ating the Administration’S Iran Policy

FROM SANCTIONS TO THE SOLEIMANI STRIKE TO ESCALATION: EVALU- ATING THE ADMINISTRATION’S IRAN POLICY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION January 14, 2020 Serial No. 116–89 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 38–916PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLIPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey STEVE WATKINS, Kansas DAVID TRONE, Maryland MIKE GUEST, Mississippi JIM COSTA, California JUAN VARGAS, California VICENTE GONZALEZ, Texas JASON STEINBAUM, Staff Director BRENDAN SHIELDS, Republican Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S Page INFORMATION REFERRED TO FOR THE RECORD Information referred ............................................................................................... -

Libya Before and After Gaddafi: an International Law Analysis

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Relazioni Internazionali Comparate Tesi di Laurea Libya Before and After Gaddafi: An International Law Analysis. Relatore Ch. Prof. Fabrizio Marrella Correlatore Ch. Prof. Antonio Trampus Correlatrice Ch.ma Prof.ssa Sara De Vido Laureando Enrica Oliveri Matricola 817727 Anno Accademico 2011 / 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS “RINGRAZIAMENTI”...................................................................................................I ABSTRACT.........…………………………………………...………...……….……….II INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................VI FIRST PART. LIBYA BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND INTERNATIONAL SANCTIONS. CHAPTER 1. The Birth of the Independent Libya, 1969 Gaddafi’s Revolution and his Political Ideology. 1.1. An Overlook on the Libyan Situation prior to Gaddafi’s Dictatorship……………..2 1.2. Gaddafi’s Education and the 1969 Great Revolution……………………………….5 1.3. Gaddafi’s Ideology, his Affinities with Nasser and the Green Book……………….8 1.4. The Constitutional, Institutional and Administrative Changes of the Seventies…..14 CHAPTER 2. The 1986 US Benghazi Bombing, the 1988 Lockerbie Attack and the Consequent International Sanctions. 2.1. An Overview on the Second Period of Gaddafi’s Dictatorship……………………21 2.2. USA and Libya: the 1986 American Benghazi and Tripoli Bombings……………25 2.3. The International Sanctions: the Lockerbie Attack and the Consequent United Nations Security Council Resolutions………………………………………………….29