Tribes and Revolution; the “Social Factor” in Muammar Gadhafi's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Québec (Canada) 21 – 26 October 2012

127th Assembly of the 127ème Assemblée de Inter-Parliamentary Union and Related Meetings l’Union interparlementaire et réunions connexes Québec City, Canada Québec, Canada 21-26 October 2012 21-26 octobre 2012 www.ipu2012uip.ca Assembly A/127/4(a)-R.1 Item 4 14 September 2012 ENFORCING THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT: THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENT IN SAFEGUARDING CIVILIANS’ LIVES Draft report submitted by Mr. L. Ramatlakane (South Africa), co-Rapporteur Introduction The IPU, the global organization of parliaments, works for peace and cooperation among peoples and for the firm establishment of representative democracy;1 as such, it has identified Enforcing the responsibility to protect: the role of parliament in safeguarding civilians’ lives as a current issue of urgent concern. The "responsibility to protect" concept was endorsed by 191 countries in a resolution (A/RES/60/1) adopted at the United Nations World Summit in 2005. It refers to the responsibility of every State to safeguard its population from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. If a State fails to protect its citizens – meaning that it is no longer upholding its responsibility as a sovereign nation – and peaceful measures have failed, the international community has a responsibility to take corrective measures, with military action being the last resort. The concept’s proper and effective operationalization and implementation have often fallen short of the resolution adopted at the World Summit. This observation has been borne out by events in Egypt, Côte d’Ivoire and Libya, and the ambiguous responses to them. It is evident that parliaments – as assembled by a body such as the IPU – should express themselves on the issue. -

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

Situation of Human Rights in Libya, and the Effectiveness of Technical Assistance and Capacity-Building Measures Received by the Government of Libya

United Nations A/HRC/43/75 General Assembly Distr.: General 23 January 2020 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-third session 24 February–20 March 2020 Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building Situation of human rights in Libya, and the effectiveness of technical assistance and capacity-building measures received by the Government of Libya Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Summary In the present report, submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to Council resolution 40/27, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights describes the situation of human rights in Libya from January to December 2019, and provides an overview of the work and technical assistance conducted by the Human Rights, Transitional Justice and Rule of Law Service of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) in cooperation with the Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR). The High Commissioner highlights key human rights issues relating to the protection of civilians in armed conflict, in particular its impact on women and children; the situation of migrants and refugees; the rights to freedom of opinion and expression; the administration of justice; and the support provided to victims of human rights violations. The High Commissioner also describes capacity-building activities conducted by UNSMIL and the implementation of the human rights due diligence policy on United Nations support to non-United Nations security forces. The High Commissioner concludes the report with recommendations for the Government of National Accord in Libya, all parties to the conflict and the international community. -

Speak Softly and Carry a Sealed Warrant: Building the International Criminal Court’S Legitimacy in the Wake of Sudan

APPEAL VOLUME 18 n 163 ARTICLE SPEAK SOFTLY AND CARRY A SEALED WARRANT: BUILDING THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT’S LEGITIMACY IN THE WAKE OF SUDAN Kai Sheffield* CITED: (2013) 18 Appeal 163-175 INTRODUCTION The Rome Statute, the constitutive treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC), sets out the goals by which the Court’s legitimacy can be measured: punishment of perpetrators, deterrence of future crimes, and positive effects on the peace, security, and well-being of the world.1 Upholding and enhancing the legitimacy of the ICC is the duty of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court,2 and Luis Moreno Ocampo, Prosecutor until June 2012, made it his project to make the ICC a “reality” which political actors “cannot ignore.”3 During his time in office, Moreno Ocampo handed over a steady stream of accused war criminals and genocidaires from states party to the Rome Statute (State Parties) to the judges in The Hague.4 However, he was much less successful in bringing defendants from non-State Parties before the Court. Under the Rome Statute, the ICC possesses a limited power of universal jurisdiction, whereby it may prosecute individuals from non-State Parties through referrals from the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).5 This power, however, is not well- * Kai Sheffield completed his J.D. at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law in the spring of 2012 and is currently an associate at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP in New York City. He completed his undergraduate degree in International Relations at the University of British Columbia. Kai wrote a shorter version of this paper as a third-year law student for Professor Michael Ignatieff’s Human Rights and International Politics class and is very grateful to Professor Ignatieff for his guidance and encouragement. -

Country Information and Guidance Libya: Actual Or Perceived Gaddafi Clan Members/Loyalists 19 August 2014

Country Information and Guidance Libya: Actual or perceived Gaddafi clan members/loyalists 19 August 2014 Preface This document provides guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling claims made by nationals/residents of Libya, as well as country of origin information (COI) about Libya. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether - in the event of a claim being refused - it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Within this instruction, links to specific guidance are those on the Home Office’s internal system. Public versions of these documents are available at https://www.gov.uk/immigration- operational-guidance/asylum-policy. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. -

Gaddafi Supporters Since 2011

Country Policy and Information Note Libya: Actual or perceived supporters of former President Gaddafi Version 3.0 April 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

A Strategy for Success in Libya

A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Why the US Must Act in Libya Now ............................................................................................................................1 Wrong Problem, Wrong Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 2 What to Do ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Reframing US Policy in Libya .................................................................................................. 5 America’s Opportunity in Libya ................................................................................................................................. 6 The US Approach in Libya ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Current Situation -

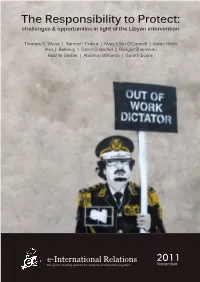

The Responsibility to Protect: Challenges & Opportunities in Light of the Libyan Intervention

The Responsibility to Protect: challenges & opportunities in light of the Libyan intervention Thomas G. Weiss | Ramesh Thakur | Mary Ellen O’Connell | Aidan Hehir Alex J. Bellamy | David Chandler | Rodger Shanahan Rachel Gerber | Abiodun Williams | Gareth Evans e-International Relations 2011 the world’s leading website for students of international politics November 1 Created in November 2007 by students from the UK universities Contents of Oxford, Leicester and Aberystwyth, e-International Relations (e-IR) is a hub of information and analysis on some of the key 4 Introduction issues in international politics. Alex Stark As well as editorials contributed by students, leading academics and policy-makers, the website contains essays, diverse 7 Whither R2P? perspectives on global news, lecture podcasts, blogs written by Thomas G. Weiss some of the world’s top professors and the very latest research news from academia, politics and international development. 12 R2P, Libya and International Politics as the Struggle for Competing Normative Architectures Ramesh Thakur 15 How to Lose a Revolution Mary Ellen O’Connell 18 The Illusion of Progress: Libya and the Future of R2P Aidan Hehir 20 R2P and the Problem of Regime Change Alex J. Bellamy 24 Libya: The End of Intervention David Chandler 26 R2P: Seeking Perfection in an Imperfect World Rodger Shanahan 28 Prevention: Core to R2P Rachel Gerber 31 R2P and Peacemaking Abiodun Williams Front page image by Joe Mariano 34 Interview: The R2P Balance Sheet After Libya Gareth Evans 2 3 Introduction Alex Stark | November 2011 he international community has a contentious The framework and scope of R2P was officially State to civil society members, that states have the perspectives has opened the floodgates to Thistory when it comes to preventing and codified at the 2005 UN World Summit. -

Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Wolfram Lacher Fault Lines of the Revolution Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya RP 4 May 2013 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2013 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the author(s). SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 3−4 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (English version of SWP-Studie 5/2013) The English translation of this study has been realised in the context of the project “Elite change and new social mobilization in the Arab world”. The project is funded by the German Foreign Office in the framework of the transformation partnerships with the Arab World and the Robert Bosch Stiftung. It cooperates with the PhD grant programme of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung. Table of Contents 5 Problems and Conclusions 7 Parameters of the Transition 9 Political Forces in the New Libya 9 Camps and Interests in Congress and Government 10 Ideological Camps and Tactical Alliances 12 Fault Lines of the Revolution 14 The Zeidan Government 14 Parliamentary and Extra-Parliamentary Islamists 14 The Grand Mufti’s Network and Influence 16 The Influence of Islamist Currents -

The Arab Community in Canada

Catalogue no. 89-621-XIE — No. 9 ISSN: 1719-7376 ISBN: 978-0-662-46473-0 Analytical Paper Profiles of Ethnic Communities in Canada The Arab Community in Canada 2001 by Colin Lindsay Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division 7th Floor, Jean Talon Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Telephone: 613-951-5979 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website at www.statcan.ca or contact us by e-mail at [email protected] or by phone from 8:30am to 4:30pm Monday to Friday at: Toll-free telephone (Canada and the United States): Enquiries line 1-800-263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Depository Services Program enquiries line 1-800-635-7943 Depository Services Program fax line 1-800-565-7757 Statistics Canada national contact centre: 1-613-951-8116 Fax line 1-613-951-0581 Information to access the product This product, catalogue no. 89-621-XIE, is available for free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.ca and select Publications. Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, the Agency has developed standards of service which its employees observe in serving its clients. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.ca under About us > Providing services to Canadians. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 30 / Tuesday, February 14, 1995 / Rules and Regulations

8300 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 30 / Tuesday, February 14, 1995 / Rules and Regulations § 300.1 Installment agreement fee. Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20220. Determinations that persons fall (a) Applicability. This section applies The full list of persons blocked pursuant within the definition of the term to installment agreements under section to economic sanctions programs ``Government of Libya'' and are thus 6159 of the Internal Revenue Code. administered by the Office of Foreign Specially Designated Nationals of Libya (b) Fee. The fee for entering into an Assets Control is available electronically are effective upon the date of installment agreement is $43. on The Federal Bulletin Board (see determination by the Director of FAC, (c) Person liable for fee. The person SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION). acting under the authority delegated by liable for the installment agreement fee FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: J. the Secretary of the Treasury. Public is the taxpayer entering into an Robert McBrien, Chief, International notice is effective upon the date of installment agreement. Programs Division, Office of Foreign publication or upon actual notice, Assets Control, tel.: 202/622±2420. whichever is sooner. § 300.2 Restructuring or reinstatement of The list of Specially Designated installment agreement fee. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Nationals in appendices A and B is a (a) Applicability. This section applies Electronic Availability partial one, since FAC may not be aware to installment agreements under section of all agencies and officers of the 6159 of the Internal Revenue Code that This document is available as an Government of Libya, or of all persons are in default. An installment agreement electronic file on The Federal Bulletin that might be owned or controlled by, or is deemed to be in default when a Board the day of publication in the acting on behalf of the Government of taxpayer fails to meet any of the Federal Register. -

DEATH of a DICTATOR Bloody Vengeance in Sirte WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DEATH OF A DICTATOR Bloody Vengeance in Sirte WATCH Death of a Dictator Bloody Vengeance in Sirte Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-952-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2012 ISBN: 1-56432-952-6 Death of a Dictator Bloody Vengeance in Sirte Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................14 I. Background ..................................................................................................................