The Earth's Atmosphere-II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fog and Low Clouds As Troublemakers During Wildfi Res

When Our Heads Are in the Clouds Sometimes water droplets do not freeze in below- Detecting fog from space Up to 60,000 ft (18,000m) freezing temperatures. This happens if they do not have Weather satellites operated by the National Oceanic The fog comes a surface (like a dust particle or an ice crystal) upon and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) collect data on on little cat feet. which to freeze. This below-freezing liquid water becomes clouds and storms. Cirrus Commercial Jetliner “supercooled.” Then when it touches a surface whose It sits looking (36,000 ft / 11,000m) temperature is below freezing, such as a road or sidewalk, NOAA operates two different types of satellites. over harbor and city Geostationary satellites orbit at about 22,236 miles Breitling Orbiter 3 the water will freeze instantly, making a super-slick icy on silent haunches (34,000 ft / 10,400m) Cirrocumulus coating on whatever it touches. This condition is called (35,786 kilometers) above sea level at the equator. At this and then moves on. Mount Everest (29,035 ft / 8,850m) freezing fog. altitude, the satellite makes one Earth orbit per day, just Carl Sandburg Cirrostratus as Earth rotates once per day. Thus, the satellite seems to 20,000 feet (6,000 m) Cumulonimbus hover over one spot below and keeps its “birds’-eye view” of nearly half the Earth at once. Altocumulus The other type of NOAA satellites are polar satellites. Their orbits pass over, or nearly over, the North and South Clear and cloudy regions over the U.S. -

On the Relationship Between Gravity Waves and Tropopause Height and Temperature Over the Globe Revealed by COSMIC Radio Occultation Measurements

atmosphere Article On the Relationship between Gravity Waves and Tropopause Height and Temperature over the Globe Revealed by COSMIC Radio Occultation Measurements Daocheng Yu 1, Xiaohua Xu 1,2,*, Jia Luo 1,3,* and Juan Li 1 1 School of Geodesy and Geomatics, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] (D.Y.); [email protected] (J.L.) 2 Collaborative Innovation Center for Geospatial Technology, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China 3 Key Laboratory of Geospace Environment and Geodesy, Ministry of Education, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.X.); [email protected] (J.L.); Tel.: +86-27-68758520 (X.X.); +86-27-68778531 (J.L.) Received: 4 January 2019; Accepted: 6 February 2019; Published: 12 February 2019 Abstract: In this study, the relationship between gravity wave (GW) potential energy (Ep) and the tropopause height and temperature over the globe was investigated using COSMIC radio occultation (RO) dry temperature profiles during September 2006 to May 2013. The monthly means of GW Ep with a vertical resolution of 1 km and tropopause parameters were calculated for each 5◦ × 5◦ longitude-latitude grid. The correlation coefficients between Ep values at different altitudes and the tropopause height and temperature were calculated accordingly in each grid. It was found that at middle and high latitudes, GW Ep over the altitude range from lapse rate tropopause (LRT) to several km above had a significantly positive/negative correlation with LRT height (LRT-H)/ LRT temperature (LRT-T) and the peak correlation coefficients were determined over the altitudes of 10–14 km with distinct zonal distribution characteristics. -

Nighttime Secondary Ozone Layer During Major Stratospheric Sudden Warmings in Specified-Dynamics WACCM Olga V

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH: ATMOSPHERES, VOL. 118, 8346–8358, doi:10.1002/jgrd.50651, 2013 Nighttime secondary ozone layer during major stratospheric sudden warmings in specified-dynamics WACCM Olga V. Tweedy,1,2 Varavut Limpasuvan,1 Yvan J. Orsolini,3,4 Anne K. Smith,5 Rolando R. Garcia,5 Doug Kinnison,5 Cora E. Randall,6,7 Ole-Kristian Kvissel,8 Frode Stordal,8 V. Lynn Harvey,6,7 and Amal Chandran 9 Received 26 March 2013; revised 5 July 2013; accepted 15 July 2013; published 9 August 2013. [1] A major stratospheric sudden warming (SSW) strongly impacts the entire middle atmosphere up to the thermosphere. Currently, the role of atmospheric dynamics on polar ozone in the mesosphere-lower thermosphere (MLT) during SSWs is not well understood. Here we investigate the SSW-induced changes in the nighttime “secondary” (90–105 km) ozone maximum by examining the dynamics and distribution of key species (like H and O) important to ozone. We use output from the National Center for Atmospheric Research Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model with “Specified Dynamics” (SD-WACCM), in which the simulation is constrained by meteorological reanalyses below 1 hPa. Composites are made based on six major SSW events with elevated stratopause episodes. Individual SSW cases of temperature and MLT nighttime ozone from the model are compared against the Sounding of the Atmosphere using Broadband Emission Radiometry observations aboard the NASA’s Thermosphere Ionosphere Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED) satellite. The evolution of ozone and major chemical trace species is associated with the anomalous vertical residual motion during SSWs and consistent with photochemical equilibrium governing the MLT nighttime ozone. -

Popular Summary of “Extratropical Stratosphere-Troposphere Mass Exchange”

Popular Summary of “Extratropical Stratosphere-Troposphere Mass Exchange” Mark Schoeberl Understanding the exchange of gases between the stratosphere and the troposphere is important for determining how pollutants enter the stratosphere and how they leave. This study does a global analysis of that the exchange of mass between the stratosphere and the troposphere. While the exchange of mass is not the same as the exchange of constituents, you can’t get the constituent exchange right if you have the mass exchange wrong. Thus this kind of calculation is an important test for models which also compute trace gas transport. In this study I computed the mass exchange for two assimilated data sets and a GCM. The models all agree that amount of mass descending from the stratosphere to the troposphere in the Northern Hemisphere extra tropics is -1 0” kg/s averaged over a year. The value for the Southern Hemisphere by about a factor of two. ( 10” kg of air is the amount of air in 100 km x 100 km area with a depth of 100 m - roughly the size of the D.C. metro area to a depth of 300 feet.) Most people have the idea that most of the mass enters the stratosphere through the tropics. But this study shows that almost 5 times more mass enters the stratosphere through the extra-tropics. This mass, however, is quickly recycled out again. Thus the lower most stratosphere is a mixture of upper stratospheric air and tropospheric air. This is an important result for understanding the chemistry of the lower stratosphere. -

Using Temperature As the Basis, the Atmosphere Is Divided Into Four Layers

Using temperature as the basis, the atmosphere is divided into four layers. The temperature decrease in the troposphere, the bottom layer in which we live, is called the "environmental lapse rate." Its average value is 6.5°C per kilometer, a figure known as the "normal lapse rate." A temperature "inversion," in which temperatures increase with height, is sometimes observed in shallow layers in the troposphere. The thickness of the troposphere is generally greater in the tropics than in polar regions. Essentially all important weather phenomena occur in the troposphere. Beyond the troposphere lies the stratosphere; the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere is known as the tropopause. In the stratosphere, the temperature at first remains constant to a height of about 20 kilometers (12 miles) before it begins a sharp increase due to the absorption of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun by ozone. The temperatures continue to increase until the stratopause is encountered at a height of about 50 kilometers (30 miles).In the mesosphere, the third layer, temperatures again decrease with height until the mesopause, some 80 kilometers (50 miles) above the surface.The fourth layer, the thermosphere, with no well-defined upper limit, consists of extremely rarefied air. Temperatures here increase with an increase in altitude.Besides layers defined by vertical variations in temperature, the atmosphere is often divided into two layers based on composition. The homosphere (zone of homogeneous composition), from Earth’s surface to an altitude of about 80 kilometers (50 miles), consists of air that is uniform in terms of the proportions of its component gases. -

Hohonu Volume 5 (PDF)

HOHONU 2007 VOLUME 5 A JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC WRITING This publication is available in alternate format upon request. TheUniversity of Hawai‘i is an Equal Opportunity Affirmative Action Institution. VOLUME 5 Hohonu 2 0 0 7 Academic Journal University of Hawai‘i at Hilo • Hawai‘i Community College Hohonu is publication funded by University of Hawai‘i at Hilo and Hawai‘i Community College student fees. All production and printing costs are administered by: University of Hawai‘i at Hilo/Hawai‘i Community College Board of Student Publications 200 W. Kawili Street Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720-4091 Phone: (808) 933-8823 Web: www.uhh.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/bosp All rights revert to the witers upon publication. All requests for reproduction and other propositions should be directed to writers. ii d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d Table of Contents 1............................ A Fish in the Hand is Worth Two on the Net: Don’t Make me Think…different, by Piper Seldon 4..............................................................................................Abortion: Murder-Or Removal of Tissue?, by Dane Inouye 9...............................An Etymology of Four English Words, with Reference to both Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law by Piper Seldon 11................................Artifacts and Native Burial Rights: Where do We Draw the Line?, by Jacqueline Van Blarcon 14..........................................................................................Ayahuasca: Earth’s Wisdom Revealed, by Jennifer Francisco 16......................................Beak of the Fish: What Cichlid Flocks Reveal About Speciation Processes, by Holly Jessop 26................................................................................. Climatic Effects of the 1815 Eruption of Tambora, by Jacob Smith 33...........................Columnar Joints: An Examination of Features, Formation and Cooling Models, by Mary Mathis 36.................... -

The Tropical Tropopause Layer in Reanalysis Data Sets

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2019-580 Preprint. Discussion started: 4 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 2 The tropical tropopause layer in reanalysis data sets 3 4 Susann Tegtmeier1, James Anstey2, Sean Davis3, Rossana Dragani4, Yayoi Harada5, Ioana 5 Ivanciu1, Robin Pilch Kedzierski1, Kirstin Krüger6, Bernard Legras7, Craig Long8, James S. 6 Wang9, Krzysztof Wargan10,11, and Jonathon S. Wright12 7 8 9 1 10 GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, 24105 Kiel, Germany 11 2Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis, ECCC, Victoria, Canada 12 3Earth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 13 Boulder, CO 80305, USA 14 4European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, Reading, RG2 9AX, UK 15 5Japan Meteorological Agency, Tokyo, 100-8122, Japan 16 6 Section for Meteorology and Oceanography, Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, 17 0315 Oslo, Norway 18 7Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, CNRS/PSL-ENS, Sorbonne University Ecole 19 Polytechnique, France 20 8Climate Prediction Center, National Centers for Environmental Prediction, National Oceanic 21 and Atmospheric Administration, College Park, MD 20740, USA 22 9Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam, Germany 23 10Science Systems and Applications, Inc., Lanham, MD 20706, USA 24 11Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, Code 610.1, NASA Goddard Space Flight 25 Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 26 12Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 1 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2019-580 Preprint. Discussion started: 4 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. -

Aviation Glossary

AVIATION GLOSSARY 100-hour inspection – A complete inspection of an aircraft operated for hire required after every 100 hours of operation. It is identical to an annual inspection but may be performed by any certified Airframe and Powerplant mechanic. Absolute altitude – The vertical distance of an aircraft above the terrain. AD - See Airworthiness Directive. ADC – See Air Data Computer. ADF - See Automatic Direction Finder. Adverse yaw - A flight condition in which the nose of an aircraft tends to turn away from the intended direction of turn. Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) – A primary FAA publication whose purpose is to instruct airmen about operating in the National Airspace System of the U.S. A/FD – See Airport/Facility Directory. AHRS – See Attitude Heading Reference System. Ailerons – A primary flight control surface mounted on the trailing edge of an airplane wing, near the tip. AIM – See Aeronautical Information Manual. Air data computer (ADC) – The system that receives and processes pitot pressure, static pressure, and temperature to present precise information in the cockpit such as altitude, indicated airspeed, true airspeed, vertical speed, wind direction and velocity, and air temperature. Airfoil – Any surface designed to obtain a useful reaction, or lift, from air passing over it. Airmen’s Meteorological Information (AIRMET) - Issued to advise pilots of significant weather, but describes conditions with lower intensities than SIGMETs. AIRMET – See Airmen’s Meteorological Information. Airport/Facility Directory (A/FD) – An FAA publication containing information on all airports, seaplane bases and heliports open to the public as well as communications data, navigational facilities and some procedures and special notices. -

Solar Energy Generation Model for High Altitude Long Endurance Platforms

Solar Energy Generation Model for High Altitude Long Endurance Platforms Mathilde Brizon∗ KTH - Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden For designing and evaluating new concepts for HALE platforms, the energy provided by solar cells is a key factor. The purpose of this thesis is to model the electrical power which can be harnessed by such a platform along any flight trajectory for different aircraft designs. At first, a model of the solar irradiance received at high altitude will be performed using the solar irradiance models already existing for ground level applications as a basis. A calculation of the efficiency of the energy generation will be performed taking into account each solar panel's position as well as shadows casted by the aircraft's structure. The evaluated set of trajectories allows a stationary positioning of a hale platform with varying wind conditions, time of day and latitude for an exemplary aircraft configuration. The qualitative effects of specific parameter changes on the harnessed solar energy is discussed as well as the fidelity of the energy generation model results. Nomenclature δ Solar declination ({) EQE Quantum efficiency (%) η Efficiency (%) hg Altitude of the aircraft (m) ◦ Γ Day angle ( ) hO3 Height of max ozone concentration(m) ◦ −2 −1 λg Longitude aircraft ( ) Id Direct irradiance (W:m .µm ) ◦ −2 −1 ! Hour angle ( ) Is Diffuse irradiance (W:m .µm ) ◦ −2 −1 φg Latitude of the aircraft ( ) Itot Total irradiance (W:m .µm ) ◦ −1 ◦ τ Rayleigh optical depth ({) kPmax;T Temperature Coefficient (%: C ) 2 A Solar cell -

1 the Atmosphere of Pluto As Observed by New Horizons G

The Atmosphere of Pluto as Observed by New Horizons G. Randall Gladstone,1,2* S. Alan Stern,3 Kimberly Ennico,4 Catherine B. Olkin,3 Harold A. Weaver,5 Leslie A. Young,3 Michael E. Summers,6 Darrell F. Strobel,7 David P. Hinson,8 Joshua A. Kammer,3 Alex H. Parker,3 Andrew J. Steffl,3 Ivan R. Linscott,9 Joel Wm. Parker,3 Andrew F. Cheng,5 David C. Slater,1† Maarten H. Versteeg,1 Thomas K. Greathouse,1 Kurt D. Retherford,1,2 Henry Throop,7 Nathaniel J. Cunningham,10 William W. Woods,9 Kelsi N. Singer,3 Constantine C. C. Tsang,3 Rebecca Schindhelm,3 Carey M. Lisse,5 Michael L. Wong,11 Yuk L. Yung,11 Xun Zhu,5 Werner Curdt,12 Panayotis Lavvas,13 Eliot F. Young,3 G. Leonard Tyler,9 and the New Horizons Science Team 1Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, TX 78238, USA 2University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249, USA 3Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, USA 4National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ames Research Center, Space Science Division, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 5The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723, USA 6George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 7The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 8Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 9Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 10Nebraska Wesleyan University, Lincoln, NE 68504 11California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 12Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, 37191 Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany 13Groupe de Spectroscopie Moléculaire et Atmosphérique, Université Reims Champagne-Ardenne, 51687 Reims, France *To whom correspondence should be addressed. -

Apihelion Vs

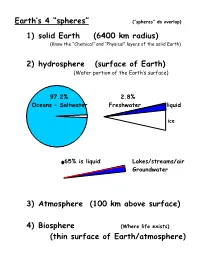

Earth’s 4 “spheres” (“spheres” do overlap) 1) solid Earth (6400 km radius) (Know the “Chemical” and “Physical” layers of the solid Earth) 2) hydrosphere (surface of Earth) (Water portion of the Earth’s surface) 97.2% 2.8% Oceans – Saltwater Freshwater liquid ice .65% is liquid Lakes/streams/air Groundwater 3) Atmosphere (100 km above surface) 4) Biosphere (Where life exists) (thin surface of Earth/atmosphere) Weather vs Climate constantly “average weather” changing 6 basic elements of weather/climate temperature of air humidity of air type & amount of cloudiness type & amount of precipitation pressure exerted by air speed & direction of wind Atmosphere Composition / Ozone Layer (pgs. 6-9) Evolution of Earth’s Atmosphere (pgs. 9-11) Exploring the Atmosphere time line for inventions/discoveries 1593 Galileo “thermometer” 1643 Torricelli barometer 1661 Boyle (P)(V)=constant 1752 Franklin kite -> lightning=electricity 1880(90) manned ballons 1900-today unmanned ballons using radiosondes = radio transmitters that send info on temperature/pressure/relative humidity today rockets & airplanes weather radar & satellites Height/Structure of Atmosphere Exosphere (above 800 km) 100 km 100 km (Ionosphere) 90 km Thermosphere 90 km 80 km 80 km 70 km 70 km 60 km Mesosphere 60 km 50 km 50 km 40 km (Ozone Layer) 40 km 30 km Stratosphere 30 km 20 km 20 km 10 km 10 km Troposphere 0 km 0 km extremely 0o hot really hot 0 100 500 1000 cold Temperature Pressure (mb) Homosphere vs Heterosphere 0-80 km above 80 km uniform distribution varies by mass of molecule N2 O He H Ionosphere located in the Thermosphere/Heterosphere N2 O ionize due to absorbing high-energy solar energy lose electrons and become +charged ions electrons are free to move Solar flares let go of lots of solar energy (charged particles) The charged particles mix with Earth’s magnetic field Charged particles are guided toward N-S magnetic poles Charged particles mix with ionosphere and cause Auroras Electromagnetic Spectrum Seasons are due to angle of sun’s rays. -

Summary of a Program Review Held at Huntsville, Alabama October 19-21, 1982

Summary of a program review held at Huntsville, Alabama October 19-21, 1982 - TECH LIBRARY KAFEI, NM lllllllsllllllRlRllffllilrml OOSSE!?b NASA Conference Publication 2259 NASA/MSFCFY-82 Atmospheric Processes Research Review Compiled by Robert E. Turner George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama Summary of a program review held at Huntsville, Alabama October 19-21, 1982 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Sclontlflc and Tochnlcal InformatIon Branch 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The productive inputs and comments from the participants and attendees in the Atmospheric Processes Research Review contributed very much to the success of the review. The opportunity provided for everyone to become better acquainted with the work of other investigators and to see how the research relates to the overall objective of NASA's Atmospheric Processes Research Program was an important aspect of the review. Appreciation is expressed to all those who participated in the review. The organizers trust that participation will provide each with a better frame of reference from which to proceed with the next year's research activities. ii PREFACE Each year NASA supports research in various disciplinary program areas. The coordination and exchange of information among those sponsored by NASA to conduct research studies are important elements of each program. The Office of Space Science and Applications and the Office of Aeronautics and Space Technology, via Announcements of Opportunity (AO), Application Notices (AN),etc., invites interested investigators throughout the country to communicate their research ideas within NASA and in institutions. The proposals in the Atmospheric Processes Research area selected and assigned to the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Atmospheric Sciences Division for technical monitorship, together with the research efforts included in the FY-82 MSFC Research and Technology Operating Plan (RTOP1 I are the source of principal focus for the NASA/MSFC FY-82 Atmospheric Processes Research Review.