Papers of Hilde Bruch Manuscript Collection No.7 of the John P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandor Ferenczi and the Budapest School of Phychoanalisis

CORRIENTES PSICOTERAPEUTICAS. News. ALSF Nº 1. SÁNDOR FERENCZI AND THE BUDAPEST SCHOOL OF PSYCHOANALYSIS1 Judit Mészáros, Ph.D. This is truly an exceptional occasion: the opening of the Sandor Ferenczi Center at the New School for Social Research. It calls to mind two moments in history that have made it possible for us to celebrate here today. The first is the founding of the New School, which has indeed been a flagship of progress in its 90 years of existence. And the Center certainly represents part of this spirit of progress. The other moment is the first latter-day international Ferenczi conference held in New York City in 1991, initiated by two of our colleagues present here, Adrienne Harris and Lewis Aron.2 Here again we see the meeting of New York and Budapest at this great event, as we do at another: as the Sandor Ferenczi Society in Budapest is honored as recipient of the 2008 Mary S. Sigourney Trust Award for our 20 years of contributing to the field of psychoanalysis. We have reason to celebrate. After half a century of apparent death, the intellectual spirit of Ferenczi has been revived by the unwavering commitment and hard work of two generations of professionals throughout the world. Ferenczi developed innovative concepts on scholarly thinking, and on the meeting points of culture and psychoanalysis. He and the members of the Budapest School represented not only Hungarian roots, but also the values, the scholarly approach, and the creativity characteristic of Central Eastern Europe in the first half of the 20th century. -

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

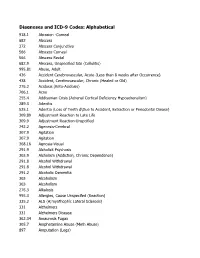

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

21Psycho BM 681-694.Qxd 9/11/06 06:44 PM Page 681

21Psycho_BM 681-694.qxd 9/11/06 06:44 PM Page 681 681 BOOK REVIEWS PROJECT FOR A SCIENTIFIC PSYCHOANALYSIS A review of Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self, by Allan N. Schore, New York & London: W.W. Norton, 2003. 403 pp and Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self, New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2003, 363 pp. JUDITH ISSROFF ELDOM does one have the privilege of reviewing work as important Sand impressive as these volumes. Along with Schore’s earlier work, Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, these two new collections con- stitute a trilogy of carefully crafted and researched papers. They also mark “a clarion call for a paradigm shift, both in psychiatry and in biology and in psychoanalytic psychotherapies.” The papers included in the two vol- umes were published during the past decade with newer material added. One cannot over-emphasize the significance of Schore’s monumental cre- ative labor. Schore convincingly argues that it is self and personality, rather than con- sciousness, that are the outstanding issues in neuroscience. The develop- ment of self and personality is bound up with affect regulation during the first year of life when the infant is dependent on mother’s auxiliary “self- object,” right-brain-mediated nonconscious “reading” of her infant’s needs and regulatory capacity. Mother both soothes and excites within her in- fant’s ability to cope without becoming traumatized. In other words, an attuned adaptive “good enough” functioning is essential for right-brain structural-functional development. The self-organization of the develop- ing brain can only occur in the finely attuned relationship with another self, another brain. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

The Addicted Subject Caught Between the Ego and the Drive: the Post-Freudian Reduction and Simplification of a Complex Clinical Problem

Psychoanalytische Perspectieven, 2000, nr. 41/42. THE ADDICTED SUBJECT CAUGHT BETWEEN THE EGO AND THE DRIVE: THE POST-FREUDIAN REDUCTION AND SIMPLIFICATION OF A COMPLEX CLINICAL PROBLEM Rik Loose It is clear that the promotion of the ego today culminates, in conformity with the utilitarian conception of man that reinforces it, in an ever more advanced realisation of man as individual, that is to say, in an isolation of the soul ever more akin to its original dereliction (Lacan, 1977 [1948]: 27). Addicts adrift in contaminated waters In a landmark article on addiction from 1933 entitled "The Psychoanalysis of Pharmacothymia (Drug Addiction)" Sandor Rado writes: "The older psychoanalytic literature contains many valuable contributions and references, particularly on alcoholism and morphinism, which attempts essentially to explain the relationship of these states to disturbances in the development of the libido function" (Rado, 1933: 61). The "older" psychoanalytic literature considers addiction to be related to a problematic development of the psychosexual stages which would lead to an inhibition or perversion of the sexual drives. The first article entirely devoted to addiction by an analyst was written by Abraham in 1908. He states that alcohol affects the sexual drives by removing resistance thereby causing increased sexual activity (Abraham, 1908: 82). The article is interesting in the sense that it sets the scene for a psychoanalytic understanding of addiction for a good few years. Abraham (1908: 89) argues that external factors (such as social influences and hereditary make-up) are not sufficient for an explanation of drunkenness. There must be an individual factor present which causes alcoholism and addiction and © www.psychoanalytischeperspectieven.be 56 RIK LOOSE this factor, he claims, is of a sexual nature. -

Female Sexuality

FEMALESEXUALITY TheEarly Psychoanalytic Controversies Editedby Russe/lGrigg, Dominique Hecq, ondCraig Smith KARNAC Early Stagesof the Oedipus Conflict 76 Melanie Klein l1 The Evolution of the Oedipus Complex in Women 159 The papers rncludeC ::-.i leanneLampl de Groot :l,ternattonal lourna, j .{braham's'Ongrns ar.d 1,2 Womanliness as a Masquerade 772 appeared rn hls Se,e::cx loan Riaiere H om osexua htl" app'ea red llv Psvchmnalvtrc Qua,:a 13 The Significance of Masochism in the Mental Lile of iohan van Ophuu-n F:er Women 183 h'omen to the Dutch Psvc: HeleneDeutsch ictnes read a paper on ( .{,nah'tical Socieh T4 The Pregenital Antecedents of the Oedipus Complex 195 Though these pape:: a Otto Fenichel 'rairtr', and though sc':r.e rt'here,they have never br 15 On FemaleHomosexuality 220 rt'ho has read these paFte!.,l HeleneDeutsch ol female sexualirr But rl : :here are two further corLqtr The Dread of Woman: Obselvations on a Specific .lebate that take place I'ett Dfference in the Dread Felt by Men and Women s:derable impact ther nac Respectively for the Opposite Sex 24r 'ieses. The papers ha...ea : I(arenHorney today'will also shon ther , s:de psl'choanalvslsor rer: The Denial of the Vagina: a Contribution to the We have correctai s Problem of the Genital Anxieties Specific to Women 253 spellrng errors in the cnFr I(arenHorney .r' accessibleversron-q e: :. the references.Thrs u^cluC Passivity, Masochism and Femininity 26 been altered to volune al Marie Bonaparte CompletePsychologrca;,i :-r Press and the lnshtute -.i P Early FemaleSexuality w5 The articles have b,,er?r Ernestlones of publication. -

Overview 2008–2020 Karina-Sirkku Kurz

Overview 2008–2020 Karina-Sirkku Kurz Karina-Sirkku Kurz is fascinated by the human body, both its physicality together with its sensorial awareness — its capacity as an object and a subject simultaneously. In her work she approaches this phenomenon and explores how people experience human form. Kurz’ photographic gaze is neither fattering nor judg mental but akin to an adaptive lyricism. Her images, which may carry visual perplexity, oscillate between expressions of dis comfort and tenderness. Photography remains her primary medium, however, be sides its visual delivery an underlayer of its sculptural aspects coexists. In this regard, the occasional handbuilt objects and surface of the photographs reveal her work's haptic potential. When Kurz is exhibiting, she is carefully considering different printing methods and a respective type of presentation for her work, which emphasises the physicality and the materiality of every single piece. Karina-Sirkku Kurz is a German-Finnish artist and photographer. She studied in Bremen, Lahti, and Helsinki, where she earned her Master’s degree from the department of photography at Aalto University. Currently, she lives in Berlin. 2 2015–2019 SUPERNATURE The photographic work in SUPERNATURE centres on the concept of the body as a malleable, sculptural entity. In this manner, aesthetic plastic surgery serves as an important context — a highly invasive practice, which revolves around designing and restructuring one‘s physical appearance according to specifc visual ideals. How does reshaping the appearance of the body affect one‘s selfimage? Additionally, how are these corporal inter ventions experienced — which indelibly alter internal tissue, membrane, and fesh? In her approach the artist elicits concepts from the book Our Strange Body (2Ο14) by dutch philosopher Jenny Slatman. -

Sullivan: Interpersonal Theory

CHAPTER 8 Sullivan: Interpersonal Theory B Overview of Interpersonal Theory B Biography of Harry Stack Sullivan B Tensions Needs Anxiety Energy Transformations B Dynamisms Malevolence Intimacy Lust Self-System Sullivan B Personifications Bad-Mother, Good-Mother B Psychological Disorders Me Personifications B Psychotherapy Eidetic Personifications B Related Research B Levels of Cognition The Pros and Cons of “Chums” for Girls and Boys Prototaxic Level Imaginary Friends Parataxic Level B Critique of Sullivan Syntaxic Level B Concept of Humanity B Stages of Development B Key Terms and Concepts Infancy Childhood Juvenile Era Preadolescence Early Adolescence Late Adolescence Adulthood 212 Chapter 8 Sullivan: Interpersonal Theory 213 he young boy had no friends his age but did have several imaginary playmates. TAt school, his Irish brogue and quick mind made him unpopular among school- mates. Then, at age 81/2, the boy experienced an intimate relationship with a 13-year-old boy that transformed his life. The two boys remained unpopular with other children, but they developed close bonds with each other. Most scholars (Alexander, 1990, 1995; Chapman, 1976; Havens, 1987) believe that the relationship between these boys—Harry Stack Sullivan and Clarence Bellinger—was at least in some ways homosexual, but others (Perry, 1982) believed that the two boys were never sexually intimate. Why is it important to know about Sullivan’s sexual orientation? This knowl- edge is important for at least two reasons. First, a personality theorist’s early life his- tory, including gender, birth order, religious beliefs, ethnic background, schooling, as well as sexual orientation, all relate to that person’s adult beliefs, conception of humanity, and the type of personality theory that that person will develop. -

The Search for the "Manchurian Candidate" the Cia and Mind Control

THE SEARCH FOR THE "MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE" THE CIA AND MIND CONTROL John Marks Allen Lane Allen Lane Penguin Books Ltd 17 Grosvenor Gardens London SW1 OBD First published in the U.S.A. by Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., and simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 1979 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 1979 Copyright <£> John Marks, 1979 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner ISBN 07139 12790 jj Printed in Great Britain by f Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland J For Barbara and Daniel AUTHOR'S NOTE This book has grown out of the 16,000 pages of documents that the CIA released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. Without these documents, the best investigative reporting in the world could not have produced a book, and the secrets of CIA mind-control work would have remained buried forever, as the men who knew them had always intended. From the documentary base, I was able to expand my knowledge through interviews and readings in the behavioral sciences. Neverthe- less, the final result is not the whole story of the CIA's attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA's destruction in 1973 of many of the key docu- ments. -

Transference and Countertransference

Washington Center for Psychoanalysis Psychoanalytic Studies Program, 2018-2019 TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTERTRANSFERENCE 18 December 2018- 19 March 2019 Tuesday: 5:30-6:45 Faculty: David Joseph and Pavel Snejnevski “I believe it is ill-advised, indeed impossible, to treat transference and countertransference as separate issues. They are two faces of the same dynamic rooted in the inextricable intertwining with others in which individual life originates and remains throughout the life of the individual in numberless elaborations, derivatives, and transformations. One of the transformations shows itself in the encounter of the psychoanalytic situation.” Hans Loewald Transference and Countertransference OVERVIEW OF THE COURSE Although it was first formulated by Freud, transference, as we currently understand it, is integral to all meaningful human relationships. In a treatment relationship characterized by the therapist’s professional but friendly interest, relative anonymity, neutrality regarding how patients conduct their lives, non-judgmental attitude, and a shared conviction that associating freely and speaking without censorship will best facilitate the goals of the treatment, patients come to experience the therapist in ways that are powerfully and unconsciously shaped by aspects of earlier important relationships. The patient is often not aware that he is “transferring” these earlier experiences to the therapist but is also often completely unaware of “transferred” reactions to the therapist that only become manifest as the treatment relationship develops. Laboratory experiments in animals demonstrate neurophysiological processes that cast light on the processes that contribute to transference reactions in humans. If a rat is trained to respond negatively to the sound of a bell that is paired with an electric shock, recordings from a single cell in the structure of the brain that responds to fear will indicate nerve firing.