Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WFP Burundi Country Brief Monaco, Netherlands, Russia, Switzerland, UNCERF, United States of March 2021 America, World Bank

WFP Burundi In Numbers Country Brief 2,499 mt of food assistance distributed March 2021 USD 820,334 cash transferred under food assistance to people affected by the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 and assets creation activities USD 8.5 m net funding requirements for the next six months (April-September 2021) 597,583 people assisted in March 2021 52% 48% Operational Updates Assistance to refugees WFP provided in-kind food assistance to 50,344 refugees (22,151 Operational Context males, 28,193 females, 13,593 children aged 0-59 months and 2,014 According to October 2020 IPC results, 11 percent of the people aged over 60 years), distributing a toal of 638 mt of food, population is facing emergency and crisis levels of food consisted of cereals, pulses, vegetable oil and salt. insecurity (phases 3 and 4). The Joint Approach to Nutrition and Assistance to returnees Food Security Assessment (JANFSA) carried out in December 2018 revealed that 44.8 percent of the population were food WFP assisted 9,590 Burundi returnees (4,699 males and 4,891 females) coming back from neighbouring countries with 452 mt of food. The insecure, with 9.7 percent in severe food insecurity. Provinces affected by severe food insecurity include Karusi (18.8 percent), assistance consisted of hot meals provided at transit centres, and a Gitega (17.5 percent), Muramvya (16.0 percent), Kirundo (14.3 three-month return package consisting of cereals, pulses, vegetable oil and salt to facilitate their reintegration in their communities. percent), and Mwaro (12.5 percent). The high population density, as well as the new influx of returnees from Tanzania and Food assistance to people affected by the socio-economic impact refugees from DRC, contributes to competition and disputes of COVID-19 over scarce natural resources. -

Student Politics in Africa: Representation and Activism

African Minds Higher Education Dynamics Series Vol. 2 Student Politics in Africa: Representation and Activism Edited by Thierry M Luescher, Manja Klemenčič and James Otieno Jowi A NOTE ABOUT THE PEER REVIEW PROCESS This open access publication forms part of the African Minds peer reviewed, academic books list, the broad mission of which is to support the dissemination of African scholarship and to foster access, openness and debate in the pursuit of growing and deepening the African knowledge base. Student Politics in Africa: Representation and Activism was reviewed by two external peers with expert knowledge in higher education in general and in African higher education in particular. Copies of the reviews are available from the publisher on request. First published in 2016 by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West 7130, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.org.za 2016 African Minds This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN: 978-1-928331-22-3 eBook edition: 978-1-928331-23-0 ePub edition: 978-1-928331-24-7 ORDERS: African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West 7130, Cape Town, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.org.za For orders from outside Africa: African Books Collective PO Box 721, Oxford OX1 9EN, UK [email protected] CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations v Acknowledgements x Foreword xi Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Thierry M Luescher, Manja Klemenčič and James Otieno Jowi Chapter 2 Student organising in African higher -

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

Burundi: the Issues at Stake

BURUNDI: THE ISSUES AT STAKE. POLITICAL PARTIES, FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND POLITICAL PRISONERS 12 July 2000 ICG Africa Report N° 23 Nairobi/Brussels (Original Version in French) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................i INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 I. POLITICAL PARTIES: PURGES, SPLITS AND CRACKDOWNS.........................1 A. Beneficiaries of democratisation turned participants in the civil war (1992-1996)3 1. Opposition groups with unclear identities ................................................. 4 2. Resorting to violence to gain or regain power........................................... 7 B. Since the putsch: dangerous games of the government................................... 9 1. Purge of opponents to the peace process (1996-1998)............................ 10 2. Harassment of militant activities ............................................................ 14 C. Institutionalisation of political opportunism................................................... 17 1. Partisan putsches and alliances of convenience....................................... 18 2. Absence of fresh political attitudes......................................................... 20 D. Conclusion ................................................................................................. 23 II WHICH FREEDOM FOR WHAT MEDIA ?...................................................... 25 A. Media -

Enabling Poor Rural People to Overcome Poverty in Burundi

©IFAD Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty in Burundi Rural poverty in Burundi Located at the heart of the African Great Lakes region, Burundi has weathered nearly two decades of conflict and troubles, which have contributed to widespread poverty. Burundi is ranked 185th out of 187 countries on the 2011 United Nations Development Programme’s human development index, and eight out of ten Burundians live below the poverty line. Per capita gross national income (GNI) in 2010 was US$170, about half its pre-war level some 20 years ago. The country is now rebuilding itself after emerging from recurrent conflict and ethnic and political rivalry. Between 1993 and 2000, an estimated 300,000 civilians were killed and 1.2 million people fled from their homes to live in refugee camps or in exile. During tha t period, life expectancy declined from 51 to 44 years, the poverty rate doubled from 33 to 67 per cent and economic recession pushed the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita down by more than 27 per cent. The long period of fighting was extremely disruptive to agriculture, which is the main source of livelihood for nine out of ten Burundians. The destruction and looting of crops and livestock, as well as general insecurity, has put rural Burundians under serious strains. Burundi was traditionally self-sufficient in food production, but because of conflict and recurrent droughts, the country has had to rely on food imports and international food aid in some regions. The vast majority of Burundi’s poor people are small-scale subsistence farmers trying to recover from the conflict and its aftermath. -

Decentralized Evaluation

based decision making decision based - d evaluation for evidence d evaluation Decentralize Decentralized Evaluation Evaluation of the Intervention for the Treatment of Moderate Acute Malnutrition in Ngozi, Kirundo, Cankuzo and Rutana 2016–2019 Prepared EvaluationFinal Report, 22 Report May 2020 WFP Burundi Evaluation Manager: Gabrielle Tremblay i | P a g e Prepared by Eric Kouam, Team Leader Aziz Goza, Quantitative Research Expert ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The evaluation team would like to thank Gabrielle Tremblay for facilitating the evaluation process, particularly the inception and data collection mission to Burundi. The team would also like to thank Patricia Papinutti, Michael Ohiarlaithe, Séverine Giroud, Gaston Nkeshimana, Jean Baptiste Niyongabo, Barihuta Leonidas, the entire nutrition team and other departments of the World Food Programme (WFP) country office in Bujumbura and the provinces of Cankuzo, Kirundo, Ngozi, Rutana and Gitega for their precious time, the documents, the data and the information made available to facilitate the development of this report. The evaluation team would also like to thank the government authorities, United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organizations and donors, as well as the health officials and workers, Mentor Mothers, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and parents of children under five who agreed to meet with us. Our gratitude also goes to the evaluation reference group and the evaluation committee for the relevant comments that helped improve the quality of this report, which we hope will be useful in guiding the next planning cycles of the MAM treatment program in Burundi. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily reflect those of the WFP. -

Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS for PEACE an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY FILIP REYNTJENS BURUNDI: Acknowledgements PROSPECTS FOR PEACE Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of Trócaire and all the orga- Internally displaced © Minority Rights Group 2000 nizations and individuals who gave financial and other people. Child looking All rights reserved assistance for this Report. after his younger Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- sibling. commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- This Report has been commissioned and is published by GIACOMO PIROZZI/PANOS PICTURES mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the For further information please contact MRG. issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in ISBN 1 897 693 53 2 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. ISSN 0305 6252 Published November 2000 MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert Typeset by Texture readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Kat- Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. rina Payne (Commissioning Editor) and Sophie Rich- mond (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR Burundi: FILIP REYNTJENS teaches African Law and Politics at A specialist on the Great Lakes Region, Professor Reynt- the universities of Antwerp and Brussels. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF BURUNDI I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 II THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGROUPMENT CAMPS ...................................... 2 III OTHER CAMPS FOR DISPLACED POPULATIONS ........................................ 4 IV HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DURING REGROUPMENT ......................... 6 Extrajudicial executions ......................................................................................... 6 Property destruction ............................................................................................... 8 Possible prisoners of conscience............................................................................ 8 V HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN THE CAMPS ........................................... 8 Undue restrictions on freedom of movement ......................................................... 8 "Disappearances" ................................................................................................... 9 Life-threatening conditions .................................................................................. 10 Insecurity in the context of armed conflict .......................................................... 11 VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DISGUISED AS PROTECTION ................ 12 VII CONCLUSION.................................................................................................... 14 VIII RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................... 15 -

BURUNDI: Floods and Landslides Flash Update No

BURUNDI: floods and landslides Flash Update No. 4 11 February 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • 3 people dead, 19 injured, and more than 11,000 displaced as a result of floods in Gatumba, Buterere, Kinama and Bubanza from 28 to 29 January 2020 • Relocation, shelter, and access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) are among the most urgent needs • Response capacity remains fragile in view of the upcoming rainy season (February to mid-May) SITUATION OVERVIEW Although it should have been the short dry season (December – January 2019), heavy rainfall combined with other underlying factors caused flooding that cost lives, displaced people internally, and caused extensive damage to shelter, infrastructure (roads, schools and bridges), and crops (especially in swamps). The north-western provinces of Cibitoke, Bubanza, Bujumbura Rural and Mairie have suffered – in varying degrees. The rains of 28-29 January 2020 particularly affected the northern and southern districts of Bujumbura Mairie, the commune of Mubimbuzi (Bujumbura Rural) and the communes of Bubanza province. • In the commune of Ntahangwa (Bujumbura Mairie), the Burundi Red Cross (BRC) and the local authorities counted 266 destroyed houses, 439 flooded houses and 1,390 internally displaced persons (IDPs). • In Bubanza, 266 houses were destroyed while 461 were partially destroyed. In addition, 3 people died, 19 were injured, and 1,507 people were displaced and left homeless. • In Mutimbuzi commune, the banks of the Rusizi River overflowed and flooded several districts of Gatumba, including Kinyinya 1&2, Muyange 1&2, Mushasha 1&2, Gaharawe (Bujumbura Mairie). According to the DTM, the first assessment reported 750 destroyed, 675 partially destroyed, and 942 flooded houses, as well as 9,743 IDPs in extreme need. -

The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi

Human Rights as Means for Peace : the Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi Author: Fidele Ingiyimbere Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2475 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2011 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE-SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTY S.T.L THESIS Human Rights as Means for Peace The Catholic Understanding of Human Rights and the Catholic Church in Burundi By Fidèle INGIYIMBERE, S.J. Director: Prof David HOLLENBACH, S.J. Reader: Prof Thomas MASSARO, S.J. February 10, 2011. 1 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 0 General Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 CHAP. I. SETTING THE SCENE IN BURUNDI ......................................................................... 8 I.1. Historical and Ecclesial Context........................................................................................... 8 I.2. 1972: A Controversial Period ............................................................................................. 15 I.3. 1983-1987: A Church-State Conflict .................................................................................. 22 I.4. 1993-2005: The Long Years of Tears................................................................................ -

WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT 7 – 13 August 2006

WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT 7 – 13 August 2006 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office for the Coordination of Bureau de Coordination des Affaires Humanitarian Affairs in Burundi Humanitaires au Burundi www.ochaburundi.org www.ochaburundi.org ACTIVITIES AND UPDATES • Training of Teachers and more classrooms: The Ministry of Education supported by UNICEF has intensified efforts to ensure quality education by training 935 teachers ahead of school resumption scheduled for next September. A two month training is under way in Mwaro for 224 teachers (from Bujumbura Rural, Cibitoke, Bubanza Makamba and Mwaro), Gitega for 223 teachers (from Gitega, Cankuzo, Karuzi, Ruyigi, Rutana and Muramvya), Ngozi for 245 (from Ngozi, Kirundo and Muyinga), and in Kayanza for 223 for the provinces of Kayanza and Muramvya. • Health, upsurge of malaria cases in Bubanza: Medical sources reported an increase in malaria cases throughout Bubanza province in July 2006 – 6,708 malaria cases against 3,742 in May. According to the provincial health officer quoted by the Burundi News agency (ABP), the most affected communes include Musigati, Rugazi and Gihanga. This is a result of insecurity prevailing in Musigati and Rugazi communes bordering the Kibira forest - families fleeing insecurity spend nights in the bush and is therefore exposed to mosquito bites. 2 of the 18 health centres in the province registered the highest number of cases: Ruce health centre (Rugazi Commune) registered 609 cases in July against 67 in May, and Kivyuka (Musigati) with 313 cases in July against 167 in May. According to the provincial doctor, drugs are available; however, the situation requires close follow-up as night displacements might continue due to increased attacks blamed on FNL rebel movement and other unidentified armed groups in the said communes. -

Will Hutus and Tutsis Live Together Peacefully ?

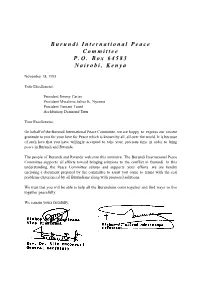

B u r u n d i I n t e r n a t i o n a l P e a c e C o m m i t t e e P . O . B o x 6 4 5 8 3 N a i r o b i , K e n y a November 18, 1995 Your Excellencies. President Jimmy Carter President Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere President Tumani TourŽ Archbishop Desmond Tutu Your Excellencies, On behalf of the Burundi International Peace Committee, we are happy to express our sincere gratitude to you for your love for Peace which is known by all, all over the world. It is because of such love that you have willingly accepted to take your precious time in order to bring peace in Burundi and Rwanda. The people of Rurundi and Rwanda welcome this initiative. The Burundi International Peace Committee supports all efforts toward bringing solutions to the conflict in Burundi. In this understanding, the Peace Committee salutes and supports your efforts. we are hereby enclosing a document prepared by the committee to assist you come to terms with the real problems experienced by all Burundians along with proposed solutions. We trust that you will be able to help all the Burundians come together and find ways to live together peacefully. We remain yours faithfully, WILL HUTUS AND TUTSIS LIVE TOGETHER PEACEFULLY ? Introduction More than two years have passed since the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye of Burundi. Since then, many people have lost their lives and continue to die. One wonders whether it will be possible again for Hutus and Tutsis to live together peacefully.