Decentralized Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enabling Poor Rural People to Overcome Poverty in Burundi

©IFAD Enabling poor rural people to overcome poverty in Burundi Rural poverty in Burundi Located at the heart of the African Great Lakes region, Burundi has weathered nearly two decades of conflict and troubles, which have contributed to widespread poverty. Burundi is ranked 185th out of 187 countries on the 2011 United Nations Development Programme’s human development index, and eight out of ten Burundians live below the poverty line. Per capita gross national income (GNI) in 2010 was US$170, about half its pre-war level some 20 years ago. The country is now rebuilding itself after emerging from recurrent conflict and ethnic and political rivalry. Between 1993 and 2000, an estimated 300,000 civilians were killed and 1.2 million people fled from their homes to live in refugee camps or in exile. During tha t period, life expectancy declined from 51 to 44 years, the poverty rate doubled from 33 to 67 per cent and economic recession pushed the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita down by more than 27 per cent. The long period of fighting was extremely disruptive to agriculture, which is the main source of livelihood for nine out of ten Burundians. The destruction and looting of crops and livestock, as well as general insecurity, has put rural Burundians under serious strains. Burundi was traditionally self-sufficient in food production, but because of conflict and recurrent droughts, the country has had to rely on food imports and international food aid in some regions. The vast majority of Burundi’s poor people are small-scale subsistence farmers trying to recover from the conflict and its aftermath. -

Health Food Security HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES

Burundi • Humanitarian Bi-Monthly report Situation Report #04 Date/Time 28 May 2009 This report was issued by Burundi office. It covers the period from 11 to 24 May 2009. The next report will be issued on or around 9 June 2009. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES - MSF prepares the phase out of its emergency nutritional operation in Kirundo Province - Repatriation from last Burundian camp in Rwanda - New refugee camp in Bwagiriza I. Situation Overview The President of Burundi has officially requested the support (logistical, technical, financial and moral) of the United Nations for the preparation and the organisation of the 2010 elections. Since March, doctors have been strike over their salaries. Developments in South Kivu and the forthcoming operation Kimia II against FDLR, are not expected to have a major impact on Burundi. The IACP contingency plan remains valid and will be updated in September. II. Humanitarian Needs and Response Health MSF is preparing to phase out its emergency nutrition programme in the Kirundo province as it expects the situation to improve as the harvests ongoing. MSF has also noted that children being referred to its nutritional centres are not as severely malnourished as when it started its emergency programme. Since February 9th, 2009; over 480 children were admitted to the nutritional stabilisation centre because of acute severe malnutrition with medical complications; some 28 children were lost because their situation was too critical when they arrived at the stabilisation centre. During this emergency nutrition programme, MSF found that 58% of the children admitted had oedemas and systematic testing of incoming patients also showed that 53.2% also had malaria. -

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture Republic of Burundi Technical Assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on Natural Resource Management and Land Use Policy Mission Dates: September 9 – 22, 2006 Constance Athman Mike Chaveas Hydrologist Africa Program Specialist Mt. Hood National Forest Office of International Programs 16400 Champion Way 1099 14th St NW, Suite 5500W Sandy, OR 97055 Washington, DC 20005 (503) 668-1672 (202) 273-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Jeanne Evenden Director of Lands Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 (801) 625-5150 [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who supported this mission to Burundi. In particular we would like acknowledge Ann Breiter, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Bujumbura for her interest in getting the US Forest Service involved in the natural resource management issues facing Burundi. We would also like to thank US Ambassador Patricia Moller for her strong interest in this work and for the support of all her staff at the US Embassy. Additionally, we are grateful to the USAID staff that provided extensive technical and logistical support prior to our arrival, as well as throughout our time in Burundi. Laura Pavlovic, Alice Nibitanga and Radegonde Bijeje were unrelentingly helpful throughout our visit and fountains of knowledge about the country, the culture, and the history of the region, as well as the various ongoing activities and actors involved in development and natural resource management programs. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Minister of Environment, Odette Kayitesi, for taking the time to meet with our team and for making key members of her staff available to accompany us during our field visits. -

Republic of Burundi Fiscal Decentralization and Local Governance

94638 Republic of Burundi Fiscal Decentralization and Local Governance Managing Trade-Offs to Promote Sustainable Reforms Burundi Public Expenditure Review OCTOBER 2014 B Republic of Burundi Fiscal Decentralization and Local Governance: Managing Trade-Offs to Promote Sustainable Reforms OCTOBER 2014 WORLD BANK Republic of Burundi Fiscal Decentralization and Local Governance: Cover Design and Text Layout:Duina ReyesManaging Bakovic Trade-Offs to Promote Sustainable Reforms i Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The endorsementboundaries, colors, or acceptance denominations, of such boundaries.and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World BankIf you translation.create a translation The World of thisBank work, shall please not be add liable the for following any content disclaimer or error along in this with translation. -

Conform Or Flee Repression and Insecurity Pushing Burundians Into Exile

CONFORM OR FLEE REPRESSION AND INSECURITY PUSHING BURUNDIANS INTO EXILE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. s © Amnesty International 2017 Except wHere otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: A CNDD-FDD (National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Forces for the Defense of (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Democracy) party supporter speaks to Burundian servicemen before the arrival of the Burundian Https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode president at a ruling CNDD-FDD rally in Cibitoke Province on July 17, 2015. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org © Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images WHere material is attributed to a copyrigHt owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First publisHed in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 16/7139/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 METHODOLOGY 6 2. VIOLATIONS AND ABUSES IN BURUNDI 8 2.1 ROLE OF THE IMBONERAKURE 8 2.2 CONSTANT THREAT OF DETENTION AND OTHER HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS 9 2.3 UNLAWFUL ARREST AND DETENTION AND UNNECESSARY USE OF FORCE 10 2.4 TORTURE AND INHUMAN, CRUEL AND DEGRADING TREATMENT IN DETENTION 10 2.5 RANSOMS 11 2.6 UNLAWFUL KILLINGS AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE 12 2.7 GENERALISED HARASSMENT AND INSECURITY 13 3. -

The AU and the Search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros

Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) is an independent mediation organisation dedicated to helping improve the global response to armed confl ict. It attempts to achieve this by mediating between warring parties and providing support to the broader mediation community. The HD Centre is driven by humanitarian values and its ultimate goal to reduce the consequences of violent confl ict, improve security, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of confl ict. It maintains a neutral stance towards the warring parties that it mediates between and, in order to maintain its impartiality it is funded by a variety of governments, private foundations and philanthropists. © Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2011 Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent and acknowledgement of the source. Front cover photography: © African Union, 78th PSC Meeting on Comoros, 9 June 2007 | © Lt. TMN Turyamumanya / Afrian Union, TFG Soldiers in Somalia queue for their fi rst organised payment exercise supervised by AMISOM troops in Mogadishu | © African Union, Water provision to neighbouring villagers in Mogadishu Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros Table of contents Part I Foreword 02 Acknowledgements 04 — Burundi case study Introduction 05 Part I: Burundi case study 09 Part II Executive summary 09 1.1 Context 10 case study — Comoros 1.2 OAU/AU intervention in the Burundi crisis 12 Part II: Comoros -

BACKGROUND of BENEFICIALS SCHOOLS the Burundi Government Has Just Set up a Project to Create Five Schools of Excellence (Year 2016- 2017) Throughout the Country

BACKGROUND OF BENEFICIALS SCHOOLS The Burundi Government has just set up a project to create five schools of excellence (Year 2016- 2017) throughout the country. The goal is to prepare the future leaders of the country who will serve in the public and private administration, scientific research centers and digital innovations. The schools are implemented throughout the country, the selection criteria of students are based on national test for the first students of 6 grades in all elementary schools of Burundi. They do a test of French and Mathematics that will determine the best Burundian students among those classified - 1st class - at the end of their curriculum of the basic school. The excellence schools are: • Lycée MUSENYI in Ngozi Province (for students from Ngozi, Kayanza, Kirundo and Muyinga provinces); • Lycée NOTRE DAME DE LA SAGESSE of Gitega province (for students from Gitega, Karuzi, Muramvya and Mwaro provinces); • Lycée KIREMBA Bururi Province (for student form Rumonge, Bururi and Makamba Provinces); • Lycée RUSENGO in Ruyigi Province (for students of Ruyigi, Cankuzo and Rutana provinces); • E.N NGAGARA in Bujumbura province (for students from Bujumbura Provinces, Bujumbura Town Hall, Bubanza and Cibitoke). The project goal is to equipping the schools of excellence with an ICT Labs and to train teachers in ICT, who will later facilitate the Education of ICT and Innovation, Creativity and digital Entrepreneurship for those students from all sections of the society. The project will then be an inspiration for the Government and all the secondary schools in Burundi. During the school holidays, the students and youths community from around the beneficial schools will also use the computers labs to benefit to the opportunity that ICT is offering in this digital age. -

EN Web Final

The Burundi Human Rights Initiative A FAÇADE OF PEACE IN A LAND OF FEAR Behind Burundi’s human rights crisis January 2020 A Façade of Peace in a Land of Fear WHAT IS THE BURUNDI HUMAN RIGHTS INITIATIVE? The Burundi Human Rights Initiative (BHRI) is an independent human rights project that aims to document the evolving human rights situation in Burundi, with a particular focus on events linked to the 2020 elections. It intends to expose the drivers of human rights violations with a view to establishing an accurate record that will help bring justice to Burundians and find a solution to the ongoing human rights crisis. BHRI’s publications will also analyse the political and social context in which these violations occur to provide a deeper and more nuanced understanding of human rights trends in Burundi. BHRI has no political affiliation. Its investigations cover human rights violations by the Burundian government as well as abuses by armed opposition groups. Carina Tertsakian and Lane Hartill lead BHRI and are its principal researchers. They have worked on human rights issues in Burundi and the Great Lakes region of Africa for many years. BHRI’s reports are the products of their collaboration with a wide range of people inside and outside Burundi. BHRI welcomes feedback on its publications as well as further information about the human rights situation in Burundi. Please write to [email protected] or +1 267 896 3399 (WhatsApp). Additional information is available at www.burundihri.org. ©2020 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative Cover photo: President Pierre Nkurunziza, 2017 ©2020 Private 2 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS Methodology 5 Acronyms 6 Summary 7 Recommendations 9 To the Burundian government and the CNDD-FDD 9 To the CNL 9 To foreign governments and other international actors 10 Map of Burundi 12 1. -

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Burundi: Complex Emergency

Emergency Plan of Action operation update Burundi: Complex Emergency Emergency appeal n° MDRBI012 GLIDE n° CE-2015-000182-BDI EPoA update n°1 Timeframe covered by this update: 1st – 15th April 2016 Point of contact: Vénérand Nzigamasabo, Head of DM Operation Manager: Andreas Sandin, IFRC East Burundi Red Cross Society (BRCS). Africa and Indian Ocean Islands. Operation timeframe: 6 months Operation start date: 31ST March 2016 End date 30th September 2016 Overall operation budget: CHF 1,532,090 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 161,922 N° of people being assisted: 100,000 people (20,000 families) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: Belgian Red Cross (FL), Belgian Red Cross (FR), Finnish Red Cross, International Committee of Red Cross, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Luxembourg Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross and Spanish Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection Unit, Concern Worldwide France Volontaire, Geographic Institute of Burundi, International Organisation for Migration, Save the Children, United Nations Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, World Food Programme, and World Vision. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: This update provides a brief overview of the Burundi Red Cross Societies actions to date in the preparations for the start of their response activities to be covered by the Emergency Appeal (in anticipation of pledges). Appeal coverage at the time of writing is 0%, donors are encouraged to support the appeal to enable BRCS to provide assistance to the targeted beneficiaries through the planned activities as detailed in the Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA). -

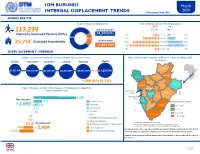

Internal Displacement Trends Report

IOM BURUNDI March 2020 INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Publica�on: May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS Graph 1: Reasons of Displacement Graph 2: Demographics of the IDP popula�on 56% 44% 117,239 Natural disasters Female Male Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) 94,340 IDPs 4% < 1 year 3% 80% 20% 11% 1-5 years 8% Other reasons 25,754 Displaced Households 18% 6-17 years 15% 22,899 IDPs 20% 18-59 years 16% 3% 60 years + 2% DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Graph 3: Trends in the number of IDPs from October 2019 to March 2020 Map 1: Net Change in presence of IDPs from February to March 2020, by province October November December January February March Kirundo 103,352 IDPs 102,722 IDPs 104,191 IDPs 112,522 IDPs 116,951 IDPs 117,239 IDPs Muyinga Cibitoke Ngozi + 288 IDPs (0.2%) Kayanza Cankuzo Bubanza Karusi Graph 4: Change in number of IDPs by reason for decrease or increase from Muramvya February to March 2020 Bujumbura Mairie Mwaro Ruyigi Gitega 2,099 Bujumbura Net Increase Rural Torren�al rains Varia�on du nombre de PDI 370 Rumonge Landslides + 2,692 152 Bururi Rutana 115 - 1,194 Strong winds 52 0 - 114 Drought 19 (-1) - (-90) Other Makamba -37 (-91) - (-428) Rese�lement outside the country -50 Absence (unknown) Net Decrease © IOM Burundi - reference map ( March 2020) -202 Rese�lement elsewhere in the country This map is for illustra�on purposes only. Names and boundaries on this map do not imply the official endorsement or acceptance by IOM. Source: IOM, IGEBU -942 Local integra�on - 2,404 The orange color in the map represents the provinces that had a decreased number of IDPs -1,173 Return to community of origin and the green color represents the provinces that had an increased number of IDPs. -

Repression and Insecurity Pushing Burundians Into Exile

CONFORM OR FLEE REPRESSION AND INSECURITY PUSHING BURUNDIANS INTO EXILE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: A CNDD-FDD (National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Forces for the Defense of (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Democracy) party supporter speaks to Burundian police before the arrival of the Burundian https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode president at a ruling CNDD-FDD rally in Cibitoke Province on July 17, 2015. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org © Carl De Souza/AFP/Getty Images Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 16/7139/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 METHODOLOGY 6 2. VIOLATIONS AND ABUSES IN BURUNDI 8 2.1 ROLE OF THE IMBONERAKURE 8 2.2 CONSTANT THREAT OF DETENTION AND OTHER HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS 9 2.3 UNLAWFUL ARREST AND DETENTION AND UNNECESSARY USE OF FORCE 10 2.4 TORTURE AND INHUMAN, CRUEL AND DEGRADING TREATMENT IN DETENTION 10 2.5 RANSOMS 11 2.6 UNLAWFUL KILLINGS AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE 12 2.7 GENERALISED HARASSMENT AND INSECURITY 13 2.7.1 PRESSURE TO JOIN CNDD-FDD OR IMBONERAKURE 13 2.7.2 FINE LINE BETWEEN TAXATION AND EXTORTION 14 2.7.3 CURFEWS AND IMBONERAKURE PATROLS 15 3. -

Burundi 19 the U.S

Angola/Burundi 19 The U.S. House of Representatives held hearings on Angola in June, showing interest in the consolidation of Angolan civil society and the role of church groups in reconciliation work. Among those who addressed the House Subcommittee on Africa was Reverend Daniel Ntoni-Nzinga, executive director of COIEPA. BURUNDI HUMAN RIGHTS DEVELOPMENTS In the year following the November 2001 installation of a transitional govern- ment comprising seventeen political parties, hopes that the nine-year-old civil war might end remained unfulfilled. Government leaders, both Hutu and Tutsi, pledged serious negotiations with the two largely Hutu rebel groups that had refused to sign the Arusha Accord of 2000, the Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Forces pour la défense de la démocratie, FDD) and the National Forces of Libera- tion (Forces nationales de libération, FNL). But as of mid-November 2002 the war dragged on with widespread suffering for the population. Both government and rebel forces killed, raped, or otherwise injured hundreds of civilians and pillaged or destroyed their property. Rebel forces ambushed civil- ian vehicles and killed and robbed the passengers. As in the past, government mili- tary and rebel groups alike coerced men, women, and children into transporting goods, a practice that sometimes placed the civilians in the direct line of fire. The government continued a program of “civilian self-defense” and did little to curb or punish human rights abuses committed by its participants. Courts continued to function badly. In early 2002 an international commission recommended prison reforms and the freeing of political prisoners, but such measures were not taken and prisoners remained in inhumane conditions in overcrowded jails: at 8,400, the prison population declined slightly from the previous year.