Burundi 19 the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mineral Industry of Burundi in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook BURUNDI [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior January 2020 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Burundi By Thomas R. Yager In 2016, the production of mineral commodities—notably can be found in previous editions of the U.S. Geological Survey gold, tantalum, tin, and tungsten—represented only a minor Minerals Yearbook, volume III, Area Reports—International— part of the economy of Burundi (United Nations Economic Africa, which are available at https://www.usgs.gov/centers/ Commission for Africa, 2017). The legislative framework for nmic/africa-and-middle-east. the mineral sector in Burundi is provided by the Mining Code of Burundi (law No. 1/21 of October 15, 2013). The legislative Reference Cited framework for the petroleum sector is provided by the Mining United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2017, Burundi, in African and Petroleum Act of 1976. Data on mineral production are statistical yearbook 2017: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, in table 1. Table 2 is a list of major mineral industry facilities. p. 113–117. (Accessed November 7, 2018, at https://www.uneca.org/sites/ More-extensive coverage of the mineral industry of Burundi default/files/PublicationFiles/asyb-2017.pdf.) TABLE 1 BURUNDI: PRODUCTION OF MINERAL COMMODITIES1 (Metric tons, gross weight, unless otherwise specified) Commodity2 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 METALS Gold, mine, Au contente kilograms 500 400 500 500 500 Niobium and tantalum, mine, columbite-tantalite concentrate: Gross weight do. 258,578 73,518 105,547 53,093 r 31,687 Nb contente do. 51,000 14,000 21,000 10,000 r 6,200 Ta contente do. -

Decentralized Evaluation

based decision making decision based - d evaluation for evidence d evaluation Decentralize Decentralized Evaluation Evaluation of the Intervention for the Treatment of Moderate Acute Malnutrition in Ngozi, Kirundo, Cankuzo and Rutana 2016–2019 Prepared EvaluationFinal Report, 22 Report May 2020 WFP Burundi Evaluation Manager: Gabrielle Tremblay i | P a g e Prepared by Eric Kouam, Team Leader Aziz Goza, Quantitative Research Expert ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The evaluation team would like to thank Gabrielle Tremblay for facilitating the evaluation process, particularly the inception and data collection mission to Burundi. The team would also like to thank Patricia Papinutti, Michael Ohiarlaithe, Séverine Giroud, Gaston Nkeshimana, Jean Baptiste Niyongabo, Barihuta Leonidas, the entire nutrition team and other departments of the World Food Programme (WFP) country office in Bujumbura and the provinces of Cankuzo, Kirundo, Ngozi, Rutana and Gitega for their precious time, the documents, the data and the information made available to facilitate the development of this report. The evaluation team would also like to thank the government authorities, United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organizations and donors, as well as the health officials and workers, Mentor Mothers, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and parents of children under five who agreed to meet with us. Our gratitude also goes to the evaluation reference group and the evaluation committee for the relevant comments that helped improve the quality of this report, which we hope will be useful in guiding the next planning cycles of the MAM treatment program in Burundi. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily reflect those of the WFP. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF BURUNDI I INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 II THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGROUPMENT CAMPS ...................................... 2 III OTHER CAMPS FOR DISPLACED POPULATIONS ........................................ 4 IV HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DURING REGROUPMENT ......................... 6 Extrajudicial executions ......................................................................................... 6 Property destruction ............................................................................................... 8 Possible prisoners of conscience............................................................................ 8 V HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN THE CAMPS ........................................... 8 Undue restrictions on freedom of movement ......................................................... 8 "Disappearances" ................................................................................................... 9 Life-threatening conditions .................................................................................. 10 Insecurity in the context of armed conflict .......................................................... 11 VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS DISGUISED AS PROTECTION ................ 12 VII CONCLUSION.................................................................................................... 14 VIII RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................... 15 -

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture Republic of Burundi Technical Assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on Natural Resource Management and Land Use Policy Mission Dates: September 9 – 22, 2006 Constance Athman Mike Chaveas Hydrologist Africa Program Specialist Mt. Hood National Forest Office of International Programs 16400 Champion Way 1099 14th St NW, Suite 5500W Sandy, OR 97055 Washington, DC 20005 (503) 668-1672 (202) 273-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Jeanne Evenden Director of Lands Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 (801) 625-5150 [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who supported this mission to Burundi. In particular we would like acknowledge Ann Breiter, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Bujumbura for her interest in getting the US Forest Service involved in the natural resource management issues facing Burundi. We would also like to thank US Ambassador Patricia Moller for her strong interest in this work and for the support of all her staff at the US Embassy. Additionally, we are grateful to the USAID staff that provided extensive technical and logistical support prior to our arrival, as well as throughout our time in Burundi. Laura Pavlovic, Alice Nibitanga and Radegonde Bijeje were unrelentingly helpful throughout our visit and fountains of knowledge about the country, the culture, and the history of the region, as well as the various ongoing activities and actors involved in development and natural resource management programs. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Minister of Environment, Odette Kayitesi, for taking the time to meet with our team and for making key members of her staff available to accompany us during our field visits. -

The AU and the Search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros

Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) is an independent mediation organisation dedicated to helping improve the global response to armed confl ict. It attempts to achieve this by mediating between warring parties and providing support to the broader mediation community. The HD Centre is driven by humanitarian values and its ultimate goal to reduce the consequences of violent confl ict, improve security, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of confl ict. It maintains a neutral stance towards the warring parties that it mediates between and, in order to maintain its impartiality it is funded by a variety of governments, private foundations and philanthropists. © Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2011 Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent and acknowledgement of the source. Front cover photography: © African Union, 78th PSC Meeting on Comoros, 9 June 2007 | © Lt. TMN Turyamumanya / Afrian Union, TFG Soldiers in Somalia queue for their fi rst organised payment exercise supervised by AMISOM troops in Mogadishu | © African Union, Water provision to neighbouring villagers in Mogadishu Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros Table of contents Part I Foreword 02 Acknowledgements 04 — Burundi case study Introduction 05 Part I: Burundi case study 09 Part II Executive summary 09 1.1 Context 10 case study — Comoros 1.2 OAU/AU intervention in the Burundi crisis 12 Part II: Comoros -

EN Web Final

The Burundi Human Rights Initiative A FAÇADE OF PEACE IN A LAND OF FEAR Behind Burundi’s human rights crisis January 2020 A Façade of Peace in a Land of Fear WHAT IS THE BURUNDI HUMAN RIGHTS INITIATIVE? The Burundi Human Rights Initiative (BHRI) is an independent human rights project that aims to document the evolving human rights situation in Burundi, with a particular focus on events linked to the 2020 elections. It intends to expose the drivers of human rights violations with a view to establishing an accurate record that will help bring justice to Burundians and find a solution to the ongoing human rights crisis. BHRI’s publications will also analyse the political and social context in which these violations occur to provide a deeper and more nuanced understanding of human rights trends in Burundi. BHRI has no political affiliation. Its investigations cover human rights violations by the Burundian government as well as abuses by armed opposition groups. Carina Tertsakian and Lane Hartill lead BHRI and are its principal researchers. They have worked on human rights issues in Burundi and the Great Lakes region of Africa for many years. BHRI’s reports are the products of their collaboration with a wide range of people inside and outside Burundi. BHRI welcomes feedback on its publications as well as further information about the human rights situation in Burundi. Please write to [email protected] or +1 267 896 3399 (WhatsApp). Additional information is available at www.burundihri.org. ©2020 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative Cover photo: President Pierre Nkurunziza, 2017 ©2020 Private 2 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS Methodology 5 Acronyms 6 Summary 7 Recommendations 9 To the Burundian government and the CNDD-FDD 9 To the CNL 9 To foreign governments and other international actors 10 Map of Burundi 12 1. -

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Burundi: Complex Emergency

Emergency Plan of Action operation update Burundi: Complex Emergency Emergency appeal n° MDRBI012 GLIDE n° CE-2015-000182-BDI EPoA update n°1 Timeframe covered by this update: 1st – 15th April 2016 Point of contact: Vénérand Nzigamasabo, Head of DM Operation Manager: Andreas Sandin, IFRC East Burundi Red Cross Society (BRCS). Africa and Indian Ocean Islands. Operation timeframe: 6 months Operation start date: 31ST March 2016 End date 30th September 2016 Overall operation budget: CHF 1,532,090 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 161,922 N° of people being assisted: 100,000 people (20,000 families) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: Belgian Red Cross (FL), Belgian Red Cross (FR), Finnish Red Cross, International Committee of Red Cross, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Luxembourg Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross and Spanish Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection Unit, Concern Worldwide France Volontaire, Geographic Institute of Burundi, International Organisation for Migration, Save the Children, United Nations Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, World Food Programme, and World Vision. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: This update provides a brief overview of the Burundi Red Cross Societies actions to date in the preparations for the start of their response activities to be covered by the Emergency Appeal (in anticipation of pledges). Appeal coverage at the time of writing is 0%, donors are encouraged to support the appeal to enable BRCS to provide assistance to the targeted beneficiaries through the planned activities as detailed in the Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA). -

Internal Displacement Trends Report

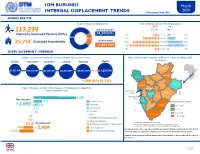

IOM BURUNDI March 2020 INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Publica�on: May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS Graph 1: Reasons of Displacement Graph 2: Demographics of the IDP popula�on 56% 44% 117,239 Natural disasters Female Male Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) 94,340 IDPs 4% < 1 year 3% 80% 20% 11% 1-5 years 8% Other reasons 25,754 Displaced Households 18% 6-17 years 15% 22,899 IDPs 20% 18-59 years 16% 3% 60 years + 2% DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Graph 3: Trends in the number of IDPs from October 2019 to March 2020 Map 1: Net Change in presence of IDPs from February to March 2020, by province October November December January February March Kirundo 103,352 IDPs 102,722 IDPs 104,191 IDPs 112,522 IDPs 116,951 IDPs 117,239 IDPs Muyinga Cibitoke Ngozi + 288 IDPs (0.2%) Kayanza Cankuzo Bubanza Karusi Graph 4: Change in number of IDPs by reason for decrease or increase from Muramvya February to March 2020 Bujumbura Mairie Mwaro Ruyigi Gitega 2,099 Bujumbura Net Increase Rural Torren�al rains Varia�on du nombre de PDI 370 Rumonge Landslides + 2,692 152 Bururi Rutana 115 - 1,194 Strong winds 52 0 - 114 Drought 19 (-1) - (-90) Other Makamba -37 (-91) - (-428) Rese�lement outside the country -50 Absence (unknown) Net Decrease © IOM Burundi - reference map ( March 2020) -202 Rese�lement elsewhere in the country This map is for illustra�on purposes only. Names and boundaries on this map do not imply the official endorsement or acceptance by IOM. Source: IOM, IGEBU -942 Local integra�on - 2,404 The orange color in the map represents the provinces that had a decreased number of IDPs -1,173 Return to community of origin and the green color represents the provinces that had an increased number of IDPs. -

January 2018

JANUARY 2018 This DTM report has been funded with the generous support of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA), the Department for International Development (DFID/UKaid) and the Swiss Agen- cy for Development and Cooperation (SDC). TABLE OF CONTENTS DTM Burundi Methodology..……….…………………………………...……………….…….…..1 IDP Presence Map…..………..…………………………………………………………..…..…….2 Highlights.……………………………………………………………………………….….….…..3 Provinces of Origin..………………………………………………………………………..….…..4 Return Intentions…………………………………….……………………………………....……5 Displacement Reasons.….……………………………………………………………….…..……6 New Displacements……..……………………………………………………………….….…….7 Displacement Trends……..…………………………………………………………….……….…8 Humanitarian Overview: Health and Food Security.………………………………………..…….9 Humanitarian Overview: Livelihoods and WASH.....……..……………….……………….……..10 Humanitarian Overview: Education and Protection……..…..……………...…………....………11 IDP Shelter Types………………………..………………………….…………………..……...…12 Shelter Construction Materials……….……………………….………...……………...….……..13 Precarious Conditions in IDP homes…….……...………………………………….…...…...…...15 Natural Disaster Cycle…….……………..…………………………...……………………..…....16 Provincial Profiles.…………………………………………………………………………….….17 Contact Information……………………………………………………………………………..18 The IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix is a comprehensive system DTM METHODOLOGY implemented to analyse and disseminate information to better unders- tand movements and needs of Internally Displaced Persons in Burundi. 1 Volunteers from the Burundian Red Cross consult -

1996 Human Rights Report: Burundi Page 1 of 13

1996 Human Rights Report: Burundi Page 1 of 13 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Burundi Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1996 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1997. BURUNDI Burundi's democratically elected president was overthrown in a military coup on July 25. Despite the coup, the National Assembly and political parties continue to operate, although under constraints. The present regime, under the self-proclaimed interim President, Major Pierre Buyoya, abrogated the 1992 Constitution and, during the so-called Transition Period, replaced the 1994 Convention of Government with a decree promulgated on September 13. Under this decree, the National Assembly does not have the power to remove the President of the Republic. The Prime Minister, appointed by the President, replaces the President in the event of the President's death or incapacity. Under the former constitution, the President of the National Assembly replaced the President. Buyoya holds power in conjunction with the Tutsi-dominated military establishment. The judicial system remains under the control of the Tutsi minority, and most citizens consider it biased against Hutus. Violent conflict among Hutu and Tutsi armed militants and the army plunged the country into a civil war marked by ethnic violence, which included fighting between the army and armed rebel groups. -

PEPFAR Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2017

PEPFAR Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2017 Strategic Direction Summary April 29, 2017 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 2.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 2.2 Investment profile 2.3 Sustainability Profile 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 2.5 Stakeholder engagement 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 4.2 Priority population prevention 4.3 Preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) 4.4HIV testing and counseling (HTC) 4.5 Facility and community-based care and support 4.6 TB/HIV 4.7 Adult treatment 4.8 Pediatric Treatment 4.9 TB/HIV 4.10 Addressing COP17 Technical Considerations 4.11 Commodities 4.12 Collaboration, Integration and Monitoring 5.0 Program Activities in Attained and Sustained Locations and Populations (Note: In COP 2017, Burundi does not have attained or sustained SNUs) 6.0 Program Support Necessary to Achieve Sustained Epidemic Control 6.1 Critical systems investments for achieving key programmatic gaps 6.2 Critical systems investments for achieving priority policies 6.3 Proposed system investments outside of programmatic gaps and priority policies 7.0 USG Management, Operations and Staffing Plan to Achieve Stated Goals Appendix A - Prioritization Appendix B - Budget Profile and Resource Projections Appendix C - Tables and Systems Investments for Section 6.0 Page -

After-Action Review

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination Bureau de Coordination Of Humanitarian Affairs in Burundi Des Affaires Humanitaires au Burundi http://ochaonline.un.org/Burundi http://ochaonline.un.org/Burundi Burundi Weekly Humanitarian News 17 November - 07 December 2008 Activities and Updates Health situation Repatriation of Burundian Refugees - Cholera epidemic in Cibitoke: Cholera epidemic continued in Cibitoke province (50 km North West of Statistics Bujumbura) with a total of 65 cases and no death During the period of 24 to 30 November, 1,477 from 10 November to 8 December 2008. The returnees arrived in Burundi. 1,464 returned from situation is now under control with the decrease of Tanzania to Makamba (incl. 1,040 from the Old new cases in the concerned health centres. A daily Settlements and 424 from Mtabila camp). 12 monitoring system continued with the support of returnees arrived from South Africa and one from health partners. Support to provincial teams is Cameroon. provided WHO, UNICEF, Solidarités, CRB, ICRC Between 01 January and 30 November 2008, 91,322 and other health partners. Burundians have returned which is more than in - Bacillary dysentery in Kirundo: Bacillary previous years since UNHCR began its voluntary dysentery epidemic continued in Kirundo province repatriation operation in 2002. In 2008, 435 (150 km north of Bujumbura) with a total of 1201 Burundians have returned in January, 1,991 in cases and 4 deaths from 10 October to 8 December February, 8,377 in March, 6,675 in April, 5,272 in 2008. WHO supported an epidemiological May, 19,635 in June, 17,504 in July, 9,640 in August, investigation which confirmed the bacillary 8,441 in September, 6,857 in October, and 6,495 in dysentery.