EN Web Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Viable Community Peace Alliances for Land Restitution in Burundi

BUILDING VIABLE COMMUNITY PEACE ALLIANCES FOR LAND RESTITUTION IN BURUNDI Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration – Peace Studies Theodore Mbazumutima Professor Geoff Harris BComm DipEd MEc PhD Supervisor ............................................ Date.............................. Dr. Sylvia Kaye BS MS PhD Co-supervisor ...................................... Date............................. May 2018 i DECLARATION I Theodore Mbazumutima declare that a. The research reported in this thesis is my original research. b. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. c. All data, pictures, graphs or other information sourced from other sources have been acknowledged accordingly – both in-text and in the References sections. d. In the cases where other written sources have been quoted, then: 1. The quoted words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced: 2. Where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks and duly referenced. ……………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is absolutely not possible to name each and every person who inspired and helped me to carry out this research. However, I would like to single out some of them. I sincerely thank Professor Geoff Harris for supervising me and tirelessly providing comments and guidelines throughout the last three years or so. I also want to thank the DUT University for giving me a place and a generous scholarship to enable me to study with them. All the staff at the university and especially the librarian made me feel valued and at home. I would like to register my sincere gratitude towards Rema Ministries (now Rema Burundi) administration and staff for giving me time off and supporting me to achieve my dream. -

Decentralized Evaluation

based decision making decision based - d evaluation for evidence d evaluation Decentralize Decentralized Evaluation Evaluation of the Intervention for the Treatment of Moderate Acute Malnutrition in Ngozi, Kirundo, Cankuzo and Rutana 2016–2019 Prepared EvaluationFinal Report, 22 Report May 2020 WFP Burundi Evaluation Manager: Gabrielle Tremblay i | P a g e Prepared by Eric Kouam, Team Leader Aziz Goza, Quantitative Research Expert ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The evaluation team would like to thank Gabrielle Tremblay for facilitating the evaluation process, particularly the inception and data collection mission to Burundi. The team would also like to thank Patricia Papinutti, Michael Ohiarlaithe, Séverine Giroud, Gaston Nkeshimana, Jean Baptiste Niyongabo, Barihuta Leonidas, the entire nutrition team and other departments of the World Food Programme (WFP) country office in Bujumbura and the provinces of Cankuzo, Kirundo, Ngozi, Rutana and Gitega for their precious time, the documents, the data and the information made available to facilitate the development of this report. The evaluation team would also like to thank the government authorities, United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organizations and donors, as well as the health officials and workers, Mentor Mothers, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and parents of children under five who agreed to meet with us. Our gratitude also goes to the evaluation reference group and the evaluation committee for the relevant comments that helped improve the quality of this report, which we hope will be useful in guiding the next planning cycles of the MAM treatment program in Burundi. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report are those of the evaluation team and do not necessarily reflect those of the WFP. -

Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS for PEACE an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY FILIP REYNTJENS BURUNDI: Acknowledgements PROSPECTS FOR PEACE Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of Trócaire and all the orga- Internally displaced © Minority Rights Group 2000 nizations and individuals who gave financial and other people. Child looking All rights reserved assistance for this Report. after his younger Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- sibling. commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- This Report has been commissioned and is published by GIACOMO PIROZZI/PANOS PICTURES mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the For further information please contact MRG. issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in ISBN 1 897 693 53 2 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. ISSN 0305 6252 Published November 2000 MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert Typeset by Texture readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Kat- Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. rina Payne (Commissioning Editor) and Sophie Rich- mond (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR Burundi: FILIP REYNTJENS teaches African Law and Politics at A specialist on the Great Lakes Region, Professor Reynt- the universities of Antwerp and Brussels. -

Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN): Burundi

U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) Burundi Sommaire / Contents BURUNDI HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT No. 4...............................................................5 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 26 July 1996 (96.7.26)..................................................9 Burundi-Canada: Canada Supports Arusha Declaration 96.8.8..............................................................11 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 14 August 1996 96.8.14..............................................13 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 15 August 1996 96.8.15..............................................15 Burundi: Statement by the US Catholic Conference and CRS 96.8.14...................................................17 Burundi: Regional Foreign Ministers Meeting Press Release 96.8.16....................................................19 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 16 August 1996 96.8.16..............................................21 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 20 August 1996 96.8.20..............................................23 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 21 August 1996 96.08.21.............................................25 Burundi: Notes from Burundi Policy Forum meeting 96.8.23..............................................................27 Burundi: IRIN Summary of Main Events for 23 August 1996 96.08.23................................................30 Burundi: Amnesty International News Service 96.8.23.......................................................................32 -

Refugies Et Deplaces Au Burundi: Desamorcer La Bombe Fonciere

REFUGIES ET DEPLACES AU BURUNDI: DESAMORCER LA BOMBE FONCIERE 7 octobre 2003 ICG Rapport Afrique N°70 Nairobi/Bruxelles TABLE DES MATIERES SYNTHESE ET RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................................i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ORIGINES POLITIQUES ET JURIDIQUE DE LA BOMBE FONCIERE BURUNDAISE................................................................................................................ 3 A. UN REGIME POST-COLONIAL D’ENCADREMENT ET D’EXPLOITATION DE LA PAYSANNERIE ...3 1. Le cas des biens des réfugiés de 1972 .......................................................................3 2. Les cas de sociétés para-étatiques de développement rural et la dilapidation des terres domaniales .......................................................................................................5 B. L’INFLATION DES SPOLIATIONS DEPUIS LE DEBUT DE LA GUERRE.........................................6 C. LE CODE FONCIER DE 1986, OUTIL IDEAL POUR LA LEGALISATION DES SPOLIATIONS .....7 III. LES CONDITIONS D’UNE APPLICATION REUSSIE DE L’ACCORD D’ARUSHA ..................................................................................................................... 9 A. LES PROPOSITIONS DE L’ACCORD D’ARUSHA .....................................................................9 B. LA CREATION D’UN SYSTEME JUDICIAIRE TRANSITIONNEL SPECIFIQUE POUR LES QUESTIONS FONCIERES ..........................................................................................................................10 -

WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT 7 – 13 August 2006

WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT 7 – 13 August 2006 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office for the Coordination of Bureau de Coordination des Affaires Humanitarian Affairs in Burundi Humanitaires au Burundi www.ochaburundi.org www.ochaburundi.org ACTIVITIES AND UPDATES • Training of Teachers and more classrooms: The Ministry of Education supported by UNICEF has intensified efforts to ensure quality education by training 935 teachers ahead of school resumption scheduled for next September. A two month training is under way in Mwaro for 224 teachers (from Bujumbura Rural, Cibitoke, Bubanza Makamba and Mwaro), Gitega for 223 teachers (from Gitega, Cankuzo, Karuzi, Ruyigi, Rutana and Muramvya), Ngozi for 245 (from Ngozi, Kirundo and Muyinga), and in Kayanza for 223 for the provinces of Kayanza and Muramvya. • Health, upsurge of malaria cases in Bubanza: Medical sources reported an increase in malaria cases throughout Bubanza province in July 2006 – 6,708 malaria cases against 3,742 in May. According to the provincial health officer quoted by the Burundi News agency (ABP), the most affected communes include Musigati, Rugazi and Gihanga. This is a result of insecurity prevailing in Musigati and Rugazi communes bordering the Kibira forest - families fleeing insecurity spend nights in the bush and is therefore exposed to mosquito bites. 2 of the 18 health centres in the province registered the highest number of cases: Ruce health centre (Rugazi Commune) registered 609 cases in July against 67 in May, and Kivyuka (Musigati) with 313 cases in July against 167 in May. According to the provincial doctor, drugs are available; however, the situation requires close follow-up as night displacements might continue due to increased attacks blamed on FNL rebel movement and other unidentified armed groups in the said communes. -

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture Republic of Burundi Technical Assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on Natural Resource Management and Land Use Policy Mission Dates: September 9 – 22, 2006 Constance Athman Mike Chaveas Hydrologist Africa Program Specialist Mt. Hood National Forest Office of International Programs 16400 Champion Way 1099 14th St NW, Suite 5500W Sandy, OR 97055 Washington, DC 20005 (503) 668-1672 (202) 273-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Jeanne Evenden Director of Lands Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 (801) 625-5150 [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who supported this mission to Burundi. In particular we would like acknowledge Ann Breiter, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Bujumbura for her interest in getting the US Forest Service involved in the natural resource management issues facing Burundi. We would also like to thank US Ambassador Patricia Moller for her strong interest in this work and for the support of all her staff at the US Embassy. Additionally, we are grateful to the USAID staff that provided extensive technical and logistical support prior to our arrival, as well as throughout our time in Burundi. Laura Pavlovic, Alice Nibitanga and Radegonde Bijeje were unrelentingly helpful throughout our visit and fountains of knowledge about the country, the culture, and the history of the region, as well as the various ongoing activities and actors involved in development and natural resource management programs. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Minister of Environment, Odette Kayitesi, for taking the time to meet with our team and for making key members of her staff available to accompany us during our field visits. -

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin N° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin n° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011 Map of emergency assistance needs in agriculture ► Increase of theft of crops and in households is for season 2012A N concerning as it is likely to bear a negative impact on food stocks and reserves from Season 2011B crops; Bugabira Busoni Giteranyi ► Whereas normally it is dry season, torrential rains with Kirundo Bwambarangwe Ntega Kirundo Rwanda hail recorded in some locations during the first half of June Gitobe Mugina Butihinda Mabayi Marangara Vumbi have caused agricultural losses and disturbed maturing Gashoho Nyamurenza Muyinga Mwumba bean crops....; Rugombo Cibitoke Muyinga Busiga Kiremba Gasorwe Murwi Kabarore Ngozi Bukinanyana Gashikanwa Kayanza Ngozi Tangara Muruta Gahombo Gitaramuka Buganda Buhinyuza Gatara Ruhororo Musigati Kayanza Kigamba ►Despite improvement of production in Season 2011A (3% Bubanza Muhanga Buhiga Bubanza Maton go Bugenyuzi Mwakiro Mishiha Gihogazi increase comparing to 2010B), the food deficits remain high Rango Mutaho Cankuzo Mpanda Karuzi Gihanga Buk eye Mutumba Rugazi Cankuzo for the second semester of the year, notably because the Mbuye Gisagara Muramvya Bugendana Nyabikere Mutimbuzi Shombo Bweru Muramvya Cendajuru imports that could supplement those production deficits are Buja Rutegama Isale Kiganda Giheta Ndava Butezi Mairie Mugongomanga reduced by the sub-regional food crisis. … ; Gisuru Kanyosha Gitega Ruyigi Buja Rusaka Nyabihanga Nyabiraba Gitega Ruyigi MutamRbuural Mwaro Kabezi Kayokwe ► Households victims of various climate disturbances Makebuko Mukike Gisozi Nyanrusange Butaganzwa Itaba Kinyinya Muhuta Bisoro Gishubi recorded in season 2011B and those with low resilience Nyabitsinda Mugamba Bugarama Ryansoro Bukirasazi capacity have not taken advantage of conducive conditions Matana Buraza Musongati Giharo D for a good production of Season 2011B and so remain Burambi R Mpinga-Kayove a Buyengero i Songa C Rutovu Rutana n Rutana a vulnerable to food insecurity. -

The AU and the Search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros

Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) is an independent mediation organisation dedicated to helping improve the global response to armed confl ict. It attempts to achieve this by mediating between warring parties and providing support to the broader mediation community. The HD Centre is driven by humanitarian values and its ultimate goal to reduce the consequences of violent confl ict, improve security, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of confl ict. It maintains a neutral stance towards the warring parties that it mediates between and, in order to maintain its impartiality it is funded by a variety of governments, private foundations and philanthropists. © Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2011 Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent and acknowledgement of the source. Front cover photography: © African Union, 78th PSC Meeting on Comoros, 9 June 2007 | © Lt. TMN Turyamumanya / Afrian Union, TFG Soldiers in Somalia queue for their fi rst organised payment exercise supervised by AMISOM troops in Mogadishu | © African Union, Water provision to neighbouring villagers in Mogadishu Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros Table of contents Part I Foreword 02 Acknowledgements 04 — Burundi case study Introduction 05 Part I: Burundi case study 09 Part II Executive summary 09 1.1 Context 10 case study — Comoros 1.2 OAU/AU intervention in the Burundi crisis 12 Part II: Comoros -

DEPARTEMENT DE LA POPULATION ±Z4 L Su U

REPUBLIQUE DU BURUNDI \1INISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR DEPARTEMENT DE LA POPULATION ±Z4 L su u REPUBLIQUE DU BURUNDI MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR DEPARTEMENT DE LA POPULATION .RÈ;CENSEM1!:NT GENERAL DE LA POPULATION 1 fiA 0 U T 1 9 7 9 TOME II VQlume IV l:t"!SU'LTATS, DEFINITIFS DE LA PROVINCE DE BURURI Bujumbura, Décembre 1983 -3- RECENSEM..ENT GENEEAL DE LA POPULATION 1 6 A 0 U T 1 979 SOMMAIRE PAGES Avant-propos 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Principaux résultats 6 2.1- Effectifs et Densités 6 2.2- Lieu de naissance et lieu de Résidence 9 2.3- Age et Sexe 11 2.4- Alphabétisation et Scolarisation 15 2.5- Population active et inactive 17 2.6- Professions et Branches d'activité 18 2.7- Ménage et Rugo 21 3. Conclusion 23 4. Annexes 24 4.1- Liste des tableaux 24 4.2- Résultats Bruts 28 -4- AVANT-PROPOS. A L'occasion de cette publication, nous rappelons que ces données ont été collectées, traitées et analysées sur base des ,anciennes limites de la province de BURURI avant'le nouveau découpage du territoire adininist'ratif. L'utilisateur trouvera des renseignements démographiques ~rès utiles dans ce volume à savoir les effectifs et, densités, le lieu de naissance et de Résidence, le sexe'et l'âge, l'alphabétisation et la scolarisation, la popula tion active et inactive, les professions et les branches d'activités, les mé- nages et Rugo et les Résultats Bruts en annexe. ' NouS adressons nos remerciements au gouvernement de la République du Burundi, aux autorités locales de la province de BURURI, au Fonds des Nations Unies pour les activités en Matière de Population (FNUAP) et à tous ceux qui, de près ou de loin, ont contribué à l'aboutiss,ement de cette grande opération. -

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Burundi: Complex Emergency

Emergency Plan of Action operation update Burundi: Complex Emergency Emergency appeal n° MDRBI012 GLIDE n° CE-2015-000182-BDI EPoA update n°1 Timeframe covered by this update: 1st – 15th April 2016 Point of contact: Vénérand Nzigamasabo, Head of DM Operation Manager: Andreas Sandin, IFRC East Burundi Red Cross Society (BRCS). Africa and Indian Ocean Islands. Operation timeframe: 6 months Operation start date: 31ST March 2016 End date 30th September 2016 Overall operation budget: CHF 1,532,090 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 161,922 N° of people being assisted: 100,000 people (20,000 families) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: Belgian Red Cross (FL), Belgian Red Cross (FR), Finnish Red Cross, International Committee of Red Cross, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Luxembourg Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross and Spanish Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection Unit, Concern Worldwide France Volontaire, Geographic Institute of Burundi, International Organisation for Migration, Save the Children, United Nations Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, World Food Programme, and World Vision. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: This update provides a brief overview of the Burundi Red Cross Societies actions to date in the preparations for the start of their response activities to be covered by the Emergency Appeal (in anticipation of pledges). Appeal coverage at the time of writing is 0%, donors are encouraged to support the appeal to enable BRCS to provide assistance to the targeted beneficiaries through the planned activities as detailed in the Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA). -

Internal Displacement Trends Report

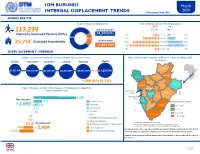

IOM BURUNDI March 2020 INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Publica�on: May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS Graph 1: Reasons of Displacement Graph 2: Demographics of the IDP popula�on 56% 44% 117,239 Natural disasters Female Male Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) 94,340 IDPs 4% < 1 year 3% 80% 20% 11% 1-5 years 8% Other reasons 25,754 Displaced Households 18% 6-17 years 15% 22,899 IDPs 20% 18-59 years 16% 3% 60 years + 2% DISPLACEMENT TRENDS Graph 3: Trends in the number of IDPs from October 2019 to March 2020 Map 1: Net Change in presence of IDPs from February to March 2020, by province October November December January February March Kirundo 103,352 IDPs 102,722 IDPs 104,191 IDPs 112,522 IDPs 116,951 IDPs 117,239 IDPs Muyinga Cibitoke Ngozi + 288 IDPs (0.2%) Kayanza Cankuzo Bubanza Karusi Graph 4: Change in number of IDPs by reason for decrease or increase from Muramvya February to March 2020 Bujumbura Mairie Mwaro Ruyigi Gitega 2,099 Bujumbura Net Increase Rural Torren�al rains Varia�on du nombre de PDI 370 Rumonge Landslides + 2,692 152 Bururi Rutana 115 - 1,194 Strong winds 52 0 - 114 Drought 19 (-1) - (-90) Other Makamba -37 (-91) - (-428) Rese�lement outside the country -50 Absence (unknown) Net Decrease © IOM Burundi - reference map ( March 2020) -202 Rese�lement elsewhere in the country This map is for illustra�on purposes only. Names and boundaries on this map do not imply the official endorsement or acceptance by IOM. Source: IOM, IGEBU -942 Local integra�on - 2,404 The orange color in the map represents the provinces that had a decreased number of IDPs -1,173 Return to community of origin and the green color represents the provinces that had an increased number of IDPs.