Buddhistroad Dynamics in Buddhist Networks in Eastern Central Asia 6Th–14Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

Basic Data Report of Kaliandi- Vihar Exploratory Tube

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By S. MARWAHA Superintending. Hydrogeologist CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOILS ..................6 IV. HYDROGEOLOGY ..................7 V. GROUND WATER RESOURCES & ESTIMATION ..................11 VI. GROUND WATER QUALITY ..................13 VII. GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT ..................16 VIII. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................17 IX. AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................18 X. AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA/SGWA ..................18 XI. RECOMMENDATIONS ..................18 TABLES : 1. Land Utilisation of Shravasti district (2008-09) 2. Source-wise area under irrigation (Ha), Shravasti, UP 3. Block-wise population covered by hand pumps, Shravasti, UP 4. Depth to water levels - Shravasti district 5. Water Level Trend Of Hydrograph Stations Of Shravasti District, U.P. 6. Block Wise Ground Water Resources As On 31.3.2009, Shravasti 7. Constituent, Desirable Limit, Permissible Limit Number Of Samples Beyond Permissible Limit & Undesirable Effect Beyond Permissible Limit 8. Chemical Analysis Result Of Water Samples, 2011, Shravasti District, U.P 9. Irrigation Water Class & Number of Samples, Shravasti District, U.P 10. Block wise Ground water Extraction structures, 2009, Shravasti, U.P PLATES : (I) Hydrogeological Map Of Shravasti District, U.P. (II) Depth To Water Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (III) Depth To Water Map (Post-Monsoon, 2012) , Shravasti District, U.P. (IV) Water Level Fluctuation Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012—Post-Monsoon,2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (V) Ground Water Resources, as on 31.3.2009, Shravasti District, U.P. 2 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 1858 ii. -

Reclaiming Buddhist Sites in Modern India: Pilgrimage and Tourism in Sarnath and Bodhgaya

RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religious Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA ©Rutika Gandhi, 2018 RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Date of Defence: August 23, 2018 Dr. John Harding Associate Professor Ph.D. Supervisor Dr. Hillary Rodrigues Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James MacKenzie Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James Linville Associate Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my beloved mummy and papa, I am grateful to my parents for being so understanding and supportive throughout this journey. iii Abstract The promotion of Buddhist pilgrimage sites by the Government of India and the Ministry of Tourism has accelerated since the launch of the Incredible India Campaign in 2002. This thesis focuses on two sites, Sarnath and Bodhgaya, which have been subject to contestations that precede the nation-state’s efforts at gaining economic revenue. The Hindu-Buddhist dispute over the Buddha’s image, the Saivite occupation of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, and Anagarika Dharmapala’s attempts at reclaiming several Buddhist sites in India have led to conflicting views, motivations, and interpretations. For the purpose of this thesis, I identify the primary national and transnational stakeholders who have contributed to differing views about the sacred geography of Buddhism in India. -

Discovering Buddhism at Home

Discovering Buddhism at home Awakening the limitless potential of your mind, achieving all peace and happiness Special Integration Experiences Required Reading Contents The Eight Places of Buddhist Pilgrimage, by Jeremy Russell 3 (Also available on Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive Website – www.lamayeshe.com) Further required reading includes the following texts: The Tantric Path of Purification, by Lama Thubten Yeshe Everlasting Rain of Nectar, by Geshe Jampa Gyatso © FPMT, Inc., 2001. All rights reserved. 1 2 The Eight Places of Buddhist Pilgrimage by Jeremy Russell Jeremy Russell was born in England and received his degree in English Literature from London University. He studied Buddhist philosophy at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, for four years. Jeremy currently lives in Dharamsala, India, editing Cho-Yang, the Journal of Tibetan Culture, and translating other material from Tibetan. Lord Buddha said: Monks, after my passing away, if all the sons and daughters of good family and the faithful, so long as they live, go to the four holy places, they should go and remember: here at Lumbini the enlightened one was born; here at Bodhgaya he attained enlightenment; here at Sarnath he turned twelve wheels of Dharma; and here at Kushinagar he entered parinirvana. Monks, after my passing away there will be activities such as circumambulation of these places and prostration to them. Thus it should be told, for they who have faith in my deeds and awareness of their own will travel to higher states. After my passing away, the new monks who come and ask of the doctrine should be told of these four places and advised that a pilgrimage to them will help purify their previously accumulated negative karmas, even the five heinous actions. -

The Monetary Economy in Buddha Period (Based on the Comparative Analysis of Literary and Archaeological Sources)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 7, Issue 6 (Jan. - Feb. 2013), PP 15-18 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org The Monetary Economy in Buddha Period (Based On the Comparative Analysis of Literary and Archaeological Sources) 1Dr. Anuradha Singh, 2 Dr. Abhay Kumar 1Assistant Professor, Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, U.P., India. 2Assistant Professor Department of History,School of Social Sciences, Guru Ghasidas Central University Bilaspur-495009, C.G., India. Archaeology reveals that the sixth BC era was the time of secondary civilization. Many cities as Shravasti, Saket, Ayodhya, Champa, Rajgriha, Kosambi and Varanasi described in Pali literature is indicative of materialistic prosperity and rich town culture. These northeastern towns of India are connected by highways to Takkasila in north, Pratishtha in south, Mrigukachha in west, Tamralipti in east and of central Kanyakubza, Ujjayini, Mathura, Sankashya and many others places. These cities were inhabited by northern black glittering earthen-pot culture. Peoples of this culture widely use iron make weapons and stricken coins. These materialistic and archaeological relics exhibit their economic strength. Artisans and businessmen were doing trading by forming union in cities. We came to know the eighteen categories of artisans. Contribution of stricken coins was very important in trading and buying-selling by these categories. By the circulation of stricken coins, trading was promoted significantly and trading becomes simplified. Various proofs of currency circulation is found in Pali scriptures and it also came to knowledge that the payments of salaries and buying was made by coins. -

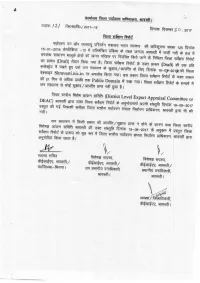

District Survey Report

1. INTRODUCTION As per gazette notification dated 15th January 2016, of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the District-Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) to be constituted by the divisional commissioner for prior environmental clearance of quarry for minor minerals. The DEIAA will scrutinize and recommend the prior environmental clearance of ministry of minor minerals on the basis of district survey report. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and mining activities along with other relevant data of district. This DSR contains details of Lease, Sand mining and Revenue which comes from minerals in the district and prepared on the basis of data collected from different concern departments and concern Mining Inspector. DISTRICT-SHRAVASTI Shravasti district is in the north western part of Uttar Pradesh covering an area of 1858.20 Sq. Km. It is a created district carved out from Bahraich district. Shravasti, which is closely associated with the life of Lord Buddha, shares border with Balrampur, Gonda & Bahraich districts. Bhinga is the district headquarters of Shravasti and is approximately 175 kilometers away from the state capital. The district is drained by river Rapti & its tributaries. In 2001 census, Shravasti has three Tehsils, viz., Bhinga, Jamunaha and Ikauna. Shravasti is a historically famous district of eastern Uttar Pradesh. As per 2011 census, total population of the district is 1,114,615 persons out of which 594,318 are males and 520,297 are females. The district has having 3 tehsils, 5 blocks and 536 inhabited villages. According to 2001 census, the district accounted 0.71 % of the State’s population in which male and female percentages are 0.72 and 0.69 respectively. -

The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Geography Faculty Publications Geography Program (SNR) 2010 The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia Robert Stoddard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographyfacpub Part of the Geography Commons Stoddard, Robert, "The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia" (2010). Geography Faculty Publications. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographyfacpub/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography Program (SNR) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geography Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art, ed. Adriana Proser (New Haven & London: Asia Society/Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 2-4, 178. Copyright © 2010 Robert H. Stoddard. The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia Robert H. Stoddard A pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place motivated by reli- where a religious leader was born, delivered spiritual guid- gious devotion. Although the term may be applied to a med- ance, or died. Pilgrimages may also occur at locations sancti- itative search for new spiritual experiences, prolonged wan- fied—according to the worldview of devotees—by miracles derings, or travel to a place of nostalgic meaning for an and similar divine phenomena. In some religions, the impor- individual, here the word refers to the physical journey to a tance of particular places is enhanced by doctrines that obli- distant site regarded as holy. As defined in this essay, pilgrim- gate adherents to make pilgrimages to designated sites. -

DIP Shravasti

0 Government of India Ministry of MSME District Industrial Profile of Shravasti District Carried out by: Branch MSME-DI, Varanasi MICRO, SMALL & MEDIUM ENTERPRISES lw[e] y/kq ,oa e/;e m|e MSME-Development Institute-Allahabad (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone: 0532-2696810, 2697468 Fax:0532-2696809 E-mail: [email protected] Web- msmediallahabad.gov.in 1 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 2 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 2 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 3 2. District at a glance 3-5 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Varanasi 5 3. Industrial Scenario Of Shravasti 5 3.1 Industry at a Glance 5-6 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 6-7 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan 7 Units In The District Shravasti 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 7 3.4.1 Major Exportable Item 7 3.4.2 Growth Trend 7 3.4.3 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 7 3.5 Medium Scale Enterprises 8 3.5.1 List of the units in Shrawasti& near by Area 8 3.5.2 Major Exportable Item 8 3.6 Potential for Development of MSMEs 8 3.6.1 Service Enterprises 8 3.6.2 Potential for new MSMEs 8 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 9 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 9 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 9 4.2 Service Sector 9 5. -

The Amida Sutra (Skt

The Amida Sutra (Skt. Smaller Sukhavativyuha Sutra) (Ch. Amituo jing) (Jp. Amida kyo) Translated by Karen Mack from the Chinese according to the Japanese Pure Land interpretation found in the contemporary Japanese translation of the Jodo Shu Research Institute, published in Kyōka Kenkyū (Journal of Jōdo Shu Edification Studies), No. 14, 2003 Translation by Imperial Edict of the Qin Kumarajiva, Yao-Qin dynasty Dharma Priest of the Tripitaka1 I (Ananda) heard the following from the Buddha, Shakyamuni. At one time Shakyamuni was at the Jetavana garden in Shravasti.2 As many as twelve hundred and fifty people assembled, and they were especially eminent monks. They were all illustrious practitioners known as arhats who had eliminated their delusions and were of great renown.3 Among them, the elders Shariputra, Mahamaudgalyayana, Mahakashyapa, Mahakatyayana, Mahakausthila, Revata, Suddhipanthaka, Nanda, Ananda, Rahula, Gavampati, Pindola Bharadvaja, Kalodayin, Mahakapphina, Vakkula, and Aniruddha, were outstanding disciples.4 There was also a vast number of bodhisattvas; the most excellent among them were the Dharma Prince Manjushri, the Bodhisattva Ajita, the Bodhisattva Gandhahastin, and the Bodhisattva Nityodyukta.5 In addition, innumerable celestial deities such as Indra had gathered.6 Then the Buddha Shakyamuni explained to the elder Shariputra: “To the far west of this world (of delusion), beyond as many as ten trillion buddha-worlds, there’s another world called Ultimate Bliss with a buddha whose name is Amitabha, who is there even now teaching the Dharma.7 Shariputra, do you know why that buddha-world is called Ultimate Bliss? It is because the people who live there never experience suffering; they are mantled in multitude forms of happiness. -

The Deer Park Project for World Peace

^LLionPO Box 6483, Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 SUMMER 1996 NEWSLETTER AND CATALOG SUPPLEMENT Anyone who has read more than a few books on Tibetan Buddhism will Sarnath, India: have encountered references to the Six Yogas ofNaropa. These six—in- ner heat, illusory body, clear light, The Deer Park Project consciousness transference, forceful projection, and the bardo yoga—rep- resent one of the most popular Ti- for World Peace betan Buddhist presentations of yo- gic technology. These teachings, given by the Indian sage Naropa to Early in 1996 during the Tibetan When Lord Buddha announced the Marpa gradually pervaded thousands Buddhist Losar celebration at Sarnath, date of his Mahaparinirvana, many of of monasteries and hermitages India, over 100 persons attended an his disciples were distraught and throughout Central Asia regardless informal consecration and dedication asked him, "What shall we do? How of sect. Tsongkhapa's discussion of ceremony for the newly completed will those who do not see you receive the Six Yogas is regarded as one of Deer Park Project for World Peace. your teachings?" Buddha told them the finest on the subject to come The temple, Padma Samye Chokhor that his followers should journey to out of Tibet. His treatise has served Ling, is situated directly between the and meditate at the holy places where as the fundamental guide to the sys- place of Buddha Shakyamuni's re- his enlightened activities occurred, tem as practiced in the more than union with his five disciples and where including: three thousand Gelukpa monasteries, he first turned the Wheel of Dharma • Lumbini, the birthplace of the Lord nunneries and hermitages across at Deer Park. -

Buddhist Tourism Report

TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE SPIRITUALISM Buddhist Tourism - Linking Cultures, Creating Livelihoods TITLE TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE SPIRITUALISM: Buddhist Tourism - Linking Cultures, Creating Livelihoods YEAR September, 2014 AUTHORS Public and Social Policies Management (PSPM) Group, YES BANK No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photoprint, COPYRIGHT microfilm or any other means without the written permission of YES BANK Ltd. & ASSOCHAM. This report is the publication of YES BANK Limited (“YES BANK”) & ASSOCHAM and so YES BANK & ASSOCHAM has editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, YES BANK & ASSOCHAM will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader's reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third party contents and third-party resources. YES BANK & ASSOCHAM takes no responsibility for third party content, advertisements or third party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. Further, YES BANK & ASSOCHAM does not assume any responsibility or liability for any loss or damage, including personal injury or death, resulting from use of this report or from any content for communications or materials available on this report. The contents are provided for your reference only. The reader/ buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by YES BANK & ASSOCHAM, it does not operate, control or endorse any information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. -

SR 97-New Text

SEPTEMBER 2019 Religious Tourism as Soft Power: Strengthening India’s Outreach to Southeast Asia Mihir Bhonsale The 25-ft Great Buddha Statue at Daijyokyo Temple, Bodh Gaya. / Photo: Mihir Bhonsale Attribution: Mihir Bhonsale, “Religious Tourism as Soft Power: Strengthening India’s Outreach to Southeast Asia”, ORF Special Report No. 97, September 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed and productive inputs, in-depth research, and stimulating discussions. ISBN 978-93-89094-83-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Religious Tourism as Soft Power: Strengthening India’s Outreach to Southeast Asia ABSTRACT A diverse culture, its vibrant democracy, and a non-aligned foreign policy have traditionally been pillars of India’s soft power. With Southeast Asia, in particular, which India considers an important region, the country derives its soft power from a shared culture that has been nurtured over the course of more than two millennia. Buddhism is part of this historic engagement, and there is a constant flow of pilgrims from the Southeast Asian countries to India even today. This special report examines the role of religious tourism in India’s soft power projection in Southeast Asia by analysing travel patterns to Buddhist sites in the Indo-Nepal plains and Buddhist heritage trails in Northeast India.