The Monetary Economy in Buddha Period (Based on the Comparative Analysis of Literary and Archaeological Sources)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage New Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISBN 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San irst Printing, 2002 " 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 " 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety, for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma, is allowed after prior notification to the author. New Cover Design ,nset photo shows the famous Reclining .uddha image at Kusinara. ,ts uni/ue facial e0pression evokes the bliss of peace 1santisukha2 of the final liberation as the .uddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the 3reat Stupa of Sanchi located near .hopal, an important .uddhist shrine where relics of the Chief 4isciples and the Arahants of the Third .uddhist Council were discovered. Printed in ,uala -um.ur, 0alaysia 1y 5a6u6aya ,ndah Sdn. .hd., 78, 9alan 14E, Ampang New Village, 78000 Selangor 4arul Ehsan, 5alaysia. Tel: 03-42917001, 42917002, a0: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATI2N This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to ,ndia from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in .uddhism, have made those 6ourneys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

District Wise EC Issued

District wise Environmental Clearances Issued for various Development Projects Agra Sl No. Name of Applicant Project Title Category Date 1 Rancy Construction (P) Ltd.S-19. Ist Floor, Complex "The Banzara Mall" at Plot No. 21/263, at Jeoni Mandi, Agra. Building Construction/Area 24-09-2008 Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110017 Development 2 G.M. (Project) M/s SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD., SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD (Hotel Project) Shilp Gram, Tajganj Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 18-12-2008 Block - 53/4, UPee Tower IIIrd Floor, Sanjav Place, Development AGRA 3 Mr. S.N. Raja, Project Coordinator, M/s GANGETIC Large Scale Shopping, Entertainment and Hotel Unit at G-1, Taj Nagari Phase-II, Basai, Building Construction/Area 19-03-2009 Developers Pvt. Ltd. C-11, Panchsheel Enclve, IIIrd Agra Development Floor, New Delhi 4 M/s Ansal Properties and Infrastructure Ltd 115, E.C. For Integrated Township, Agra Building Construction/Area 07-10-2009 Ansal Bhawan, 16, K.G. Marg, New Delhi-110001 Development 5 Chief Engineer, U.P.P.W.D., Agra Zone, Agra. “Strengthening and widening road to 6 Lane from kheria Airport via Idgah Crosing, Taj Infrastructure 11-09-2008 Mahal in Agra City.” 6 Mr. R.K. Gaud, Technical Advisor, Construction & Solid Waste Management Scheme in Agra City. Infrastructure 02-09-2008 Design Services, U.P. Jal Nigam, 2 Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Lucknow-226001 7 Agra Development Authority, Authority Office ADA Height, Agra Phase II Fatehbad Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 29-12-2008 Jaipur House AGRA. Development 8 M/s Nikhil Indus Infrastructure Ltd., Mr. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage ew Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISB: 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San First Printing, 2002 – 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 – 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety , for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma , is allowed after prior notification to the author. ew Cover Design Inset photo shows the famous Reclining Buddha image at Kusinara. Its unique facial expression evokes the bliss of peace ( santisukha ) of the final liberation as the Buddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the Great Stupa of Sanchi located near Bhopal, an important Buddhist shrine where relics of the Chief Disciples and the Arahants of the Third Buddhist Council were discovered. Printed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by: Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd., 68, Jalan 14E, Ampang New Village, 68000 Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel: 03-42916001, 42916002, Fax: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATIO This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to India from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in Buddhism, have made those journeys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

Towards a More Realistic History of Plough Cultivation in Early India

Towards a More Realistic History of Plough Cultivation in Early India GYULA WOJTILLA Agriculture has been the main occupation in India several millennia.1 In agri- culture, plough cultivation has always played the most significant role.2 The aim of this study is to revisit some commonly accepted theses on ploughing technique and the plough in scholarly literature, to analyse the different plough types as they appear in Sanskrit texts and archaeological evidence and take an unbiased standpoint on the question whether there were substantial changes in this technique or not. My investigations broadly cover the long peri- od which is generally called early India.3 It goes without saying that almost all leading historians of the independent India touched upon the role of the plough in Indian economic history. As they conceived it, this surplus is due to the widespread use of a sophisticated type of the plough and a series of innovations in agricultural practices. The pioneer of this line of research is D. D. Kosambi, a man of genius4 and a dedicated Marxist, and to whom “his familiarity with the Maharashtrian coun- tryside gave an insight into the readings of early texts.”5 As he puts it, “early cities after the ruin of Harappā and Mohenjo-dāro implied heavier stress upon 1 Gy. Wojtilla, „Kṛṣiparāśara” in Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 3 (1976), 377. 2 Cf. Gyula Wojtilla, „The Plough as Described in the Kṛṣiparāśara,” in Altorientali- sche Forschungen 5 (1977), 246.; Laping, Johannes, Die landwirtschaftliche Produktion in Indien. Ackerbau-Technologie und traditionale Agrargesellschaft dargestellt nach dem Arthaśāstra und Dharmaśāstra, Beitrāge zur Südasien-Forschung, Südasien-Institut Universität Heidelberg 62, Wiesbaden 1982, v. -

Indian Tourist Sites – in the Footsteps of the Buddha

INDIAN TOURIST SITES – IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE BUDDHA Adarsh Batra* Abstract The Chinese pilgrims Fa Hien and Hsuan Chwang). Across the world and throughout the ages, religious people have made The practice of pilgrimages. The Buddha Buddhism flourished long in himself exhorted his followers to India, perhaps reaching a zenith in visit what are now known as the the seventh century AD. After this great places of pilgrimage: it began to decline because of the Lumbini, Bodhgaya, Sarnath, invading Muslim armies, and by the Rajgir, Nalanda and twelfth century the practice of the Kushinagar. The actions of the Dharma had become sparse in its Buddha in each of these places are homeland. Thus, the history of described within the canons of the the Buddhist places of pilgrimage scriptures of the various traditions of from the thirteenth to the mid- his teaching, such as the sections on nineteenth centuries is obscure Vinaya, and also in various and they were mostly forgotten. compendia describing his life. The However, it is remarkable that sites themselves have now been they all remained virtually undis- identified once more with the aid turbed by the conflicts and develop- of records left by three pilgrims of ments of society during that period. the past (The great Emperor Ashoka, Subject only to the decay of time *The author has a Ph.D. in Tourism from Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra (K.U.K.), India. He has published extensively in Tourism and Travel Magazines. Currently he is a lecturer in MA- TRM program in the Graduate School of Business of Assumption University of Thailand. -

Basic Data Report of Kaliandi- Vihar Exploratory Tube

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF SHRAVASTI DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By S. MARWAHA Superintending. Hydrogeologist CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOILS ..................6 IV. HYDROGEOLOGY ..................7 V. GROUND WATER RESOURCES & ESTIMATION ..................11 VI. GROUND WATER QUALITY ..................13 VII. GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT ..................16 VIII. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................17 IX. AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................18 X. AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA/SGWA ..................18 XI. RECOMMENDATIONS ..................18 TABLES : 1. Land Utilisation of Shravasti district (2008-09) 2. Source-wise area under irrigation (Ha), Shravasti, UP 3. Block-wise population covered by hand pumps, Shravasti, UP 4. Depth to water levels - Shravasti district 5. Water Level Trend Of Hydrograph Stations Of Shravasti District, U.P. 6. Block Wise Ground Water Resources As On 31.3.2009, Shravasti 7. Constituent, Desirable Limit, Permissible Limit Number Of Samples Beyond Permissible Limit & Undesirable Effect Beyond Permissible Limit 8. Chemical Analysis Result Of Water Samples, 2011, Shravasti District, U.P 9. Irrigation Water Class & Number of Samples, Shravasti District, U.P 10. Block wise Ground water Extraction structures, 2009, Shravasti, U.P PLATES : (I) Hydrogeological Map Of Shravasti District, U.P. (II) Depth To Water Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (III) Depth To Water Map (Post-Monsoon, 2012) , Shravasti District, U.P. (IV) Water Level Fluctuation Map (Pre-Monsoon, 2012—Post-Monsoon,2012), Shravasti District, U.P. (V) Ground Water Resources, as on 31.3.2009, Shravasti District, U.P. 2 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 1858 ii. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

Buddhistroad Dynamics in Buddhist Networks in Eastern Central Asia 6Th–14Th Centuries

BuddhistRoad Dynamics in Buddhist Networks in Eastern Central Asia 6th–14th Centuries BuddhistRoad Paper 6.1 Special Issue ANCIENT CENTRAL ASIAN NETWORKS. RETHINKING THE INTERPLAY OF RELIGIONS, ART AND POLITICS ACROSS THE TARIM BASIN (5TH–10TH C.) Edited by ERIKA FORTE BUDDHISTROAD PAPER Peer reviewed ISSN: 2628-2356 DOI: 10.13154/rub.br.116.101 BuddhistRoad Papers are licensed under the Creative‐Commons‐Attribution Non- Commercial‐ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). You can find this publication also on the BuddhistRoad project homepage: https://buddhistroad.ceres.rub.de/en/publications/ Please quote this paper as follows: Ciro Lo Muzio, “Brahmanical Deities in Foreign Lands: The Fate of Skanda in Buddhist Central Asia,” BuddhistRoad Paper 6.1 Special Issue: Central Asian Networks. Rethinking the Interplay of Religions, Art and Politics across the Tarim Basin (5th–10th c.), ed. Erika Forte (2019): 8–43. CONTACT: Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Carmen Meinert BuddhistRoad | Ruhr-Universität Bochum | Center for Religious Studies (CERES) Universitätsstr. 90a | 44789 Bochum | Germany Phone: +49 (0)234 32-21683 | Fax: +49 (0) 234/32- 14 909 Email: [email protected] | Email: [email protected] Website: https://buddhistroad.ceres.rub.de/ BuddhistRoad is a project of SPONSORS: This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 725519). CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ANCIENT CENTRAL ASIAN NETWORKS Erika Forte ............................................................................................ 4–7 BRAHMANICAL DEITIES IN FOREIGN LANDS: THE FATE OF SKANDA IN BUDDHIST CENTRAL ASIA Ciro Lo Muzio ..................................................................................... 8–43 THE EIGHT PROTECTORS OF KHOTAN RECONSIDERED: FROM KHOTAN TO DUNHUANG Xinjiang Rong and Lishuang Zhu ..................................................... -

Reclaiming Buddhist Sites in Modern India: Pilgrimage and Tourism in Sarnath and Bodhgaya

RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religious Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA ©Rutika Gandhi, 2018 RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Date of Defence: August 23, 2018 Dr. John Harding Associate Professor Ph.D. Supervisor Dr. Hillary Rodrigues Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James MacKenzie Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James Linville Associate Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my beloved mummy and papa, I am grateful to my parents for being so understanding and supportive throughout this journey. iii Abstract The promotion of Buddhist pilgrimage sites by the Government of India and the Ministry of Tourism has accelerated since the launch of the Incredible India Campaign in 2002. This thesis focuses on two sites, Sarnath and Bodhgaya, which have been subject to contestations that precede the nation-state’s efforts at gaining economic revenue. The Hindu-Buddhist dispute over the Buddha’s image, the Saivite occupation of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, and Anagarika Dharmapala’s attempts at reclaiming several Buddhist sites in India have led to conflicting views, motivations, and interpretations. For the purpose of this thesis, I identify the primary national and transnational stakeholders who have contributed to differing views about the sacred geography of Buddhism in India. -

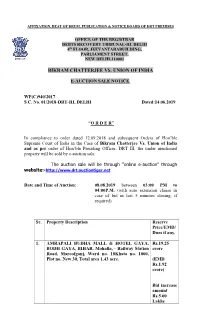

Bikram Chatterjee Vs. Union of India

AFFIXATION, BEAT OF DRUM, PUBLICATION & NOTICE BOARD OF DRT PREMISES OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR DEBTS RECOVERY TRIBUNAL-III, DELHI 4th FLOOR, JEEVANTARABUILDING, PARLIAMENT STREET, NEW DELHI-110001 BIKRAM CHATTERJEE VS. UNION OF INDIA E-AUCTION SALE NOTICE. WP(C)940/2017 S.C. No. 01/2018-DRT-III, DELHI Dated:14.06.2019 “O R D E R” In compliance to order dated 12.09.2018 and subsequent Orders of Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in the Case of Bikram Chatterjee Vs. Union of India and as per order of Hon’ble Presiding Officer, DRT III, the under mentioned property will be sold by e-auction sale. The auction sale will be through “online e-auction” through website:-http://www.drt.auctiontiger.net Date and Time of Auction: 08.08.2019 between 03:00 PM to 04:00P.M. (with auto extension clause in case of bid in last 5 minutes closing, if required). Sr. Property Description Reserve Price/EMD/ Dues if any. 1. AMRAPALI BUDHA MALL & HOTEL GAYA, Rs.19.25 BODH GAYA, BIHAR, Mohalla, - Railway Station crore Road, Maroofganj, Ward no. 18Khata no. 1000, Plot no. New 30, Total area 1.43 acre. (EMD Rs.1.92 crore) Bid increase amount Rs.5.00 Lakhs 2. AMRAPALI JAIPUR PROPERTIES: Rs.18 Crore 1) Hitech City-II- 14 Plots Nos. EMD Rs.1.8 162(452.86 sq.yds),168(300 Sq.yds), Crore 258(407.78 sq.yds) ,6(402.78 sq.yds) , 10(565.97sq.yds.),11(606.25 sq.yds.), 12(646.53 Sq.yds.,13(686.81sq.yds.), Bid increase 14(1123.11sq.yds.,15(609.72 sq.yds.), amount 16(509.38 sq.yds.) ,17(455 sq.yds.), Rs.5.00 18(400.63 sq.yds.),19(424.31 sq.yds. -

D. D. Kosambi History and Society

D. D. KOSAMBI ON HISTORY AND SOCIETY PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETATION DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF BOMBAY, BOMBAY PREFACE Man is not an island entire unto himself nor can any discipline of the sciences or social sciences be said to be so - definitely not the discipline of history. Historical studies and works of historians have contributed greatly to the enrichment of scientific knowledge and temper, and the world of history has also grown with and profited from the writings in other branches of the social sciences and developments in scientific research. Though not a professional historian in the traditional sense, D. D. Kosambi cre- ated ripples in the so-called tranquil world of scholarship and left an everlasting impact on the craft of historians, both at the level of ideologi- cal position and that of the methodology of historical reconstruction. This aspect of D. D. Kosambi s contribution to the problems of historical interpretation has been the basis for the selection of these articles and for giving them the present grouping. There have been significant developments in the methodology and approaches to history, resulting in new perspectives and giving new meaning to history in the last four decades in India. Political history continued to dominate historical writings, though few significant works appeared on social history in the forties, such as Social and Rural Economy of North- ern India by A. N. Bose (1942-45); Studies in Indian Social Polity by B. N. Dutt (1944), and India from Primitive Communism to Slavery by S. A. Dange (1949). It was however with Kosambi’s An Introduction to the study of Indian History (1956), that historians focussed their attention more keenly on modes of production at a given level of development to understand the relations of production - economic, social and political.