Europeanization and De-Europeanization of Turkish Asylum and Migration Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya's Conflict

LIBYA’S BRIEF / 12 CONFLICT Nov 2019 A very short introduction SERIES by Wolfgang Pusztai Freelance security and policy analyst * INTRODUCTION Eight years after the revolution, Libya is in the mid- dle of a civil war. For more than four years, inter- national conflict resolution efforts have centred on the UN-sponsored Libya Political Agreement (LPA) process,1 unfortunately without achieving any break- through. In fact, the situation has even deteriorated Summary since the onset of Marshal Haftar’s attack on Tripoli on 4 April 2019.2 › Libya is a failed state in the middle of a civil war and increasingly poses a threat to the An unstable Libya has wide-ranging impacts: as a safe whole region. haven for terrorists, it endangers its north African neighbours, as well as the wider Sahara region. But ter- › The UN-facilitated stabilisation process was rorists originating from or trained in Libya are also a unsuccessful because it ignored key political threat to Europe, also through the radicalisation of the actors and conflict aspects on the ground. Libyan expatriate community (such as the Manchester › While partially responsible, international Arena bombing in 2017).3 Furthermore, it is one of the interference cannot be entirely blamed for most important transit countries for migrants on their this failure. way to Europe. Through its vast oil wealth, Libya is also of significant economic relevance for its neigh- › Stabilisation efforts should follow a decen- bours and several European countries. tralised process based on the country’s for- mer constitution. This Conflict Series Brief focuses on the driving factors › Wherever there is a basic level of stability, of conflict dynamics in Libya and on the shortcomings fostering local security (including the crea- of the LPA in addressing them. -

Looking Into Iraq

Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch cc79-cover.qxp 28/07/2005 15:27 Page 2 Chaillot Paper Chaillot n° 79 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) beca- Looking into Iraq me an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the ISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a semi- nar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered Edited by Walter Posch Edited by Walter by the ISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/ESDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s Website: www.iss-eu.org cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 1 Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch Institute for Security Studies European Union Paris cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 2 Institute for Security Studies European Union 43 avenue du Président Wilson 75775 Paris cedex 16 tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org Director: Nicole Gnesotto © EU Institute for Security Studies 2005. -

QATAR UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences

QATAR UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences The Evolution of the Turkish-Qatari Relations from 2002 to 2013: Convergence of Policies, Identities and Interests A Thesis in the Gulf Studies Master‟s Program by Ozgur Pala © 2014 Ozgur Pala Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts September 2014 Declaration To the best of my knowledge, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person or institution, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree in any university or other institution. Name: Ozgur Pala Signature: _________________________________ Date: _______________ 1 Committee The thesis of Ozgur Pala was reviewed and approved by the following: We, the committee members listed below, accept and approve the Thesis of the student named above. To the best of this committee‟s knowledge, the Thesis conforms the requirements of Qatar University, and we endorse this Thesis for examination. Supervisor: Dr. Khaled Al-Mezaini Signature: _________________________________ Date: _______________ Committee Member: Dr. Abdullah Baabood Signature: _________________________________ Date: _______________ Committee Member: Dr. Steven Wright Signature: _________________________________ Date: _______________ External Examiner: Dr. Birol Baskan Signature: _________________________________ Date: _______________ 2 Abstract This study investigates the dynamics that shaped the Turkish-Qatari relations from 2002 to 2013. First, through a rigorous survey of the literature, it probes the Turkish-Gulf Arab relations from late 1970s until 2000s with a view to pinpointing prominent dynamics. In light of these general dynamics, the study then zeroes in on the regional and domestic motivations that facilitated a political alignment between Ankara and Doha. -

Turkish Militias and Proxies Erdoğan Has Created a Private Military and Paramilitary System

Turkish Militias and Proxies Erdoğan has created a private military and paramilitary system. He deploys this apparatus for domestic and foreign operations without official oversight. Dr. Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak and Dr. Jonathan Spyer Drs. Yanarocak and Spyer are senior fellows at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security (JISS). Executive Summary Since 2010, centralized authority has collapsed in many Middle East states, including Libya, Iraq, Syria and Yemen. States able to support, mobilize, and make use of irregular and proxy military formations to project power enjoy competitive advantages in this environment. Under President Recep Tayypp Erdoğan and the AKP, Turkey seeks to be the dominant regional force, projecting power over neighboring countries and across seas. In cooperation with a variety of bodies, most significantly the SADAT military contracting company and the Syrian National Army, Turkey has developed over the last decade a large pool of well-trained, easily deployed, and effortlessly disposable proxy forces as a tool of power projection, with a convenient degree of plausible deniability. When combined with Turkish non-official, but governmentally directed and well- established groups such as the Gray Wolves, it becomes clear that Erdoğan now has a private military and paramilitary system at his disposal. The use of proxies is rooted in methods developed by the Turkish "deep state" well before the AKP came to power. Ironically, the tools forged to serve the deep state's Kemalist, anti-Islamist (and anti-Kurdish) purposes now serve an Islamist, neo- Ottoman (and, once again, anti-Kurdish) agenda. Erdoğan deploys this apparatus for domestic and foreign operations without official oversight. -

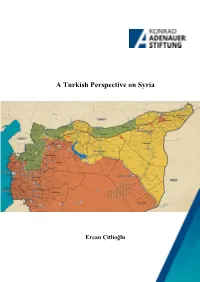

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

F-4 Phantom-Ii Metu & Odtü Teknokent Qatar Armed

VOLUME 14 . ISSUE 98 . YEAR 2020 METU & ODTÜ TEKNOKENT TURKEY’S PIONEER IN UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY THE STATE OF QATAR AND COOPERATION QATAR ARMED FORCES F-4 PHANTOM-II FLIGHT ROUTE IN TURKEY & WORLD T70 GETTING READY FOR ITS MAIDEN FLIGHT! ISSN 1306 5998 INTERNATIONAL FUTURE SOLDIER CONFERENCE 29-30 SEPTEMBER 2020 Sheraton-Ankara Within the scope of the planned conference program, panels, presentations, and discussions will be held in the following related technology fields: • Combat Clothing, Individual Equipment & Balistic Protection • Weapons, Sensors, Non Lethal Weapons, Ammunition • Power Solutions • Soft Target Protection • Soldier Physical, Mental and Cognitive Performance INTERNATIONAL • Robotics and Autonomous Systems SOLDIECONFERENCE R • Medical FUTURE • C4ISTAR Systems ifscturkey.com • Exoskeleton Technology • CBRN • Logistics Capability organised by supported by supported by supported by in cooperation with Publisher 6 34 Hatice Ayşe EVERS Editor in Chief Ayşe AKALIN [email protected] Managing Editor Cem AKALIN [email protected] International Relations Director Şebnem AKALIN [email protected] Turkey & Qatar Foul-Weather Friends! Editor İbrahim SÜNNETÇİ [email protected] Administrative Coordinator Yeşim BİLGİNOĞLU YÖRÜK [email protected] 48 Correspondent Saffet UYANIK [email protected] A Message from the President F-4 Phantom II Flight Translation of Defense Industries Prof. Route in Turkey & Tanyel AKMAN İsmail DEMİR on the Measures [email protected] Taken Against COVID-19 in World Turkey Editing Mona Melleberg YÜKSELTÜRK Graphics & Design Gülsemin BOLAT Görkem ELMAS [email protected] 12 Photographer Sinan Niyazi KUTSAL Advisory Board (R) Major General Fahir ALTAN (R) Navy Captain Zafer BETONER Prof Dr. -

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated August 27, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44533 SUMMARY R44533 Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy August 27, 2021 The State of Qatar, a small Arab Gulf monarchy which has about 300,000 citizens in a total population of about 2.4 million, has employed its ample financial resources to exert Kenneth Katzman regional influence, often independent of the other members of the Gulf Cooperation Specialist in Middle Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Eastern Affairs Oman) alliance. Qatar has fostered a close defense and security alliance with the United States and has maintained ties to a wide range of actors who are often at odds with each other, including Sunni Islamists, Iran and Iran-backed groups, and Israeli officials. Qatar’s support for regional Muslim Brotherhood organizations and its Al Jazeera media network have contributed to a backlash against Qatar led by fellow GCC states Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain, joined by Egypt and a few other governments, severed relations with Qatar and imposed limits on the entry and transit of Qatari nationals and vessels in their territories, waters, and airspace. The Trump Administration sought a resolution of the dispute, in part because the rift was hindering U.S. efforts to formalize a “Middle East Strategic Alliance” of the United States, the GCC, and other Sunni-led countries in the region to counter Iran. Qatar has countered the Saudi-led pressure with new arms purchases and deepening relations with Turkey and Iran. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921 Al-Khatrash, F. A. How to cite: Al-Khatrash, F. A. (1970) British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9812/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. BRITISH POLITICAL RELATIONS WITH KUWAIT 1890-1921 . by F.A. AL-KHATRASH B.A. 'Ain Shams "Cairo" A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Durham October 1970 CONTENTS Page Preface i - iii / Chapter One General History of Kuwait from 1890-1899 1 References 32 Chapter Two International Interests in Kuwait 37 References 54 Chapter Three Turkish Relations with Kuwait 1900-1906 57 References 84 J Chapter Four British Political Relations with Kuwait 1904-1921 88 References 131 Conclusion 135 Appendix One Exclusive Agreement: The Kuwaiti sheikh and Britain 23 January 1899 139 Appendix Two British Political Representation in the Persian Gulf 1890-1921 141 Appendix Three United Kingdom*s recognition of Kuwait as an Independent State under British Protection. -

The Rising Costs of Turkey's Syrian Quagmire Crisis Group Europe Report N°230, 30 April 2014 Page 45

The Rising Costs of Turkey’s Syrian Quagmire Europe Report N°230 | 30 April 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Turkey Adapts its Humanitarian Response ..................................................................... 2 A. Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Safety without Status..................................................... 2 1. As the world’s best shelters reach their limit ....................................................... 4 2. Syrians spread through Turkey’s urban spaces ................................................... 6 3. Syrian children miss out on schooling ................................................................. 9 4. Turkey’s many Aleppos ........................................................................................ 10 5. A new Syrian working class .................................................................................. 10 B. Turkey’s Lifeline to Northern Syria ........................................................................... 12 1. “Zero point” -

Deepening Syrian Crisis: What Kind of Strategy Should Turkmen Follow?

ORSAM REVIEW OFORSAM REVIEW OF REGIONAL AFFAIRS REGIONAL AFFAIRS NO.41, MARCH 2016 No.41, MARCH 2016 DEEPENING SYRIAN CRISIS: WHAT KIND OF STRATEGY SHOULD TURKMEN FOLLOW? Cemil Doğaç İpek Cemil Doğaç İpek presently pursues Turkmen, one of the oldest communities of Syria, his studies as a doctoral student at the Department of International Relations have struggled with the in human attacks of both of Karadeniz Technical University Assad regime and terrorist organizations since up- and as research assistant at the Department of International Relations rising started in Syria in 2011. Syrian Turkmen to- of Atatürk University. He completed day fight on four different fronts in order to protect his undergraduate education at the the lands where they have lived for centuries and Department of International Relations of Gazi University. He received his their identities. It was expected that a new period master’s degree from the Department would start in Syria in 2016 within the framework of International Relations of Gazi University with a dissertation titled of Geneva-Vienna processes. However, the hopes ‘Francophonie: An Ensemble have been shattered for now and Geneva talks are of French Speaking Countries delayed. Turkmen, one of the oldest communities (Frankofoni: Fransızca Konuşan Ülkeler Topluluğu)’. He prepared of Syria, have not been included in the internation- a program of 52 episodes named al preparatory works on the new political process. “Turkey and the Middle East (Türkiye ve Ortadoğu)” for French broadcast In this study, we will discuss the current situation on TRT. International Organizations, of the deepening Syrian crisis and the political and Turkish States and Communities, legal strategy that Syrian Turkmen should follow in Turkey-France Relations are among the field of his studies. -

The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle

ANALYSIS PAPER Number 34, October 2014 THE U.S.-TURKEY-ISRAEL TRIANGLE Dan Arbell The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2014 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu Acknowledgements I would like to thank Haim and Cheryl Saban for their support of this re- search. I also wish to thank Tamara Cofman Wittes for her encouragement and interest in this subject, Dan Byman for shepherding this process and for his continuous sound advice and feedback, and Stephanie Dahle for her ef- forts to move this manuscript through the publication process. Thank you to Martin Indyk for his guidance, Dan Granot and Clara Schein- mann for their assistance, and a special thanks to Michael Oren, a mentor and friend, for his strong support. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my wife Sarit; without her love and support, this project would not have been possible. The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle The Center for Middle East Policy at BROOKINGS ii About the Author Dan Arbell is a nonresident senior fellow with Israel’s negotiating team with Syria (1993-1996), the Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings, and later as deputy chief of mission at the Israeli and a scholar-in-residence with the department of Embassy in Tokyo, Japan (2001-2005). -

Irregular Labour Migration in Turkey and Situation of Migrant Workers in the Labour Market

IRREGULAR LABOUR MIGRATION IN TURKEY AND SITUATION OF MIGRANT WORKERS IN THE LABOUR MARKET Gülay TOKSÖZ Seyhan ERDOĞDU Selmin KAŞKA October 2012 IOM International Organization for Migration This research is conducted under the “Supporting Turkey’s Efforts to Formulate and Implement an Overall Policy Framework to Manage Migration” project funded by Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and implemented by International organization for Migration (IOM) Mission to Turkey in coordination with the Asylum and Migration Bureau of the Ministry of Interior. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Preface A number of people have made valuable contributions to this survey, finalized in the short period of six months. We would like to extend our sincere thanks, especially to Dr. Nazlı Şenses, Emel Coşkun and Bilge Cengiz, whose contribution went far beyond research assistance. We would also like to thank everyone who assisted in data collection, analysis, and interview phases of the study. We initiated our field research in İstanbul with Engin Çelik’s connections. Although we worked with him shortly, his contribution was invaluable in this regard. Mehmet Akif Kara conducted some of the interviews in İstanbul, while providing us with numerous useful connections at the same time. A teacher at Katip Kasım Primary School, Hüdai Morsümbül, whom we met by coincidence during İstanbul field research, helped us get through to migrants in Kumkapı and other locations as well as allowing us to observe migrants’ local life around Kumkapı region.