Re-Casting the Hollywood Indian: Technology Integration at Sequoyah Schools Lee M. Adcock III a Dissertation Submitted to the Fa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory

DANGEROUSLY FREE: OUTLAWS AND NATION-MAKING IN LITERATURE OF THE INDIAN TERRITORY by Jenna Hunnef A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Jenna Hunnef 2016 Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory Jenna Hunnef Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2016 Abstract In this dissertation, I examine how literary representations of outlaws and outlawry have contributed to the shaping of national identity in the United States. I analyze a series of texts set in the former Indian Territory (now part of the state of Oklahoma) for traces of what I call “outlaw rhetorics,” that is, the political expression in literature of marginalized realities and competing visions of nationhood. Outlaw rhetorics elicit new ways to think the nation differently—to imagine the nation otherwise; as such, I demonstrate that outlaw narratives are as capable of challenging the nation’s claims to territorial or imaginative title as they are of asserting them. Borrowing from Abenaki scholar Lisa Brooks’s definition of “nation” as “the multifaceted, lived experience of families who gather in particular places,” this dissertation draws an analogous relationship between outlaws and domestic spaces wherein they are both considered simultaneously exempt from and constitutive of civic life. In the same way that the outlaw’s alternately celebrated and marginal status endows him or her with the power to support and eschew the stories a nation tells about itself, so the liminality and centrality of domestic life have proven effective as a means of consolidating and dissenting from the status quo of the nation-state. -

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Hosts Keetoowah Cherokee Language Classes Throughout the Tribal Jurisdictional Area on an Ongoing Basis

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: United Keetoowah (ki-tu’-wa ) Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Tribal website(s): www.keetoowahcherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” Original Homeland Archeologists say that Keetoowah/Cherokee families began migrating to a new home in Arkansas by the late 1790's. A Cherokee delegation requested the President divide the upper towns, whose people wanted to establish a regular government, from the lower towns who wanted to continue living traditionally. On January 9, 1809, the President of the United States allowed the lower towns to send an exploring party to find suitable lands on the Arkansas and White Rivers. Seven of the most trusted men explored locations both in what is now Western Arkansas and also Northeastern Oklahoma. The people of the lower towns desired to remove across the Mississippi to this area, onto vacant lands within the United States so that they might continue the traditional Cherokee life. -

The Lost Arts Project - 1988

The Lost Arts Project - 1988 The Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. and the Cherokee Nation partnered in 1988 to create the Lost Arts Program focusing on the preservation and revival of cultural arts. A new designation was created for Master Craftsmen who not only mastered their art, but passed their knowledge on to the next generation. Stated in the original 1988 brochure: “The Cherokee people are at a very important time in history and at a crucial point in making provisions for their future identity as a distinct people. The Lost Arts project is concerned with the preservation and revival of Cherokee cultural practices that any be lost in the passage from one generation to another. The project is concerned with capturing the knowledge, techniques, individual commitment available to us and heritage received from Cherokee folk artists and developing educational and cultural preservation programs based on their knowledge and experience.” Artists had to be Cherokee and nominated by at least two people in the community. When selected, they were designated as “Living National Treasures.” 24 1 Do you know these Treasures? Lyman Vann - 1988 Bow Making Mattie Drum - 1990 Weaving Rogers McLemore - 1990 Weaving Hester Guess - 1990 Weaving Sally Lacy - 1990 Weaving Stella Livers - 1990 Basketry Eva Smith - 1991 Turtle Shell Shackles Betty Garner - 1993 Basketry Vivian Leaf Bush -1993 Turtle Shell Shackles David Neugin - 1994 Bow Making Vivian Elaine Waytula - 1995 Basketry Richard Rowe 1996 Carving Lee Foreman - 1999 Marble Making Original Lost Arts Program Exhibit Flyer- 1988 Mildred Justice Ketcher - 1999 Basketry Albert Wofford - 1999 Gig Making/Carving Willie Jumper - 2001 Stickball Sticks Sam Lee Still - 2002 Carving Linda Mouse-Hansen - 2002 Basketry Unfortunately, we have not been able to locate information, pictures or examples of art from the following Treasures. -

The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19Th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 "Behold Me and This Great Babylon I Have Built": The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L. Castelow Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION "BEHOLD ME AND THIS GREAT BABYLON I HAVE BUILT": THE LIFE AND WORK OF SOPHIA SAWYER, 19TH CENTURY MISSIONARY AND TEACHER AMONG THE CHEROKEES By TERI L. CASTELOW A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Teri L. Castelow defended on August 12, 2004. ______________________________ Victoria Maria MacDonald Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Elna Green Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Sande Milton Committee Member ______________________________ Emanuel Shargel Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Carolyn Herrington, Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies ___________________________________ Richard Kunkel, Dean, College of Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the assistance of several people for their support over the extended period it took to complete the degree requirements and dissertation for my Doctor of Philosophy degree. I would like to thank the many friends and family who have offered encouragement along the way and who did not criticize me for being a perpetual student. My parents, Paul and Nora Peasley, provided moral support and encouragement, as well as occasional child-care so I could complete research and dissertation chapters. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. LIFE HISTORY OF SAMMY STILL, A TRADITIONAL WESTERN CHEROKEE IN MODERN AMERICA By Juliette E. Sligar Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in PartialFulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Public Anthropology Chair: Richard J. Dent"'' (\ Cesare Marino Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Date 2005 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1425664 Copyright 2005 by Sligar, Juliette E. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1425664 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple Name 76001760 Arnwine Cabin TN 61 Anderson Norris 19760316 92000411 Bear Creek Road Checking Station Jct. of S. Illinois Ave. and Bear Creek Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 92000410 Bethel Valley Road Checking Station Jct. of Bethel Valley and Scarboro Rds. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 91001108 Brannon, Luther, House 151 Oak Ridge Tpk. Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS 03000697 Briceville Community Church and Cemetery TN 116 Anderson Briceville 20030724 06000134 Cross Mountain Miners' Circle Circle Cemetery Ln. Anderson Briceville 20060315 10000936 Daugherty Furniture Building 307 N Main St Anderson Clinton 20101129 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 75001726 Edwards‐‐Fowler House 3.5 mi. S of Lake City on Dutch Valley Rd. Anderson 19750529 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 11000830 Fort Anderson on Militia Hill Vowell Mountain Rd. Anderson 20111121 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 04001459 Fraterville Miners' Circle Cemetery Leach Cemetery Ln. Anderson 20050105 City) 92000407 Freels Cabin Freels Bend Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS Old Edgemoor Rd. between Bethel Valley Rd. and Melton Hill 91001107 Jones, J. B., House Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS Lake 05001218 McAdoo, Green, School 101 School St. Anderson Clinton 20051108 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 14000446 Norris Dam State Park Rustic Cabins Historic District 125 Village Green Cir. Anderson 20140725 City) 75001727 Norris District Town of Norris on U.S. 441 Anderson Norris 19750710 Tennessee Valley Authority Hydroelectric 16000165 Norris Hydrolectric Project 300 Powerhouse Way Anderson Norris 20160412 System, 1933‐1979 MPS Roughly bounded by East Dr., W. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works Progress Administration Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Projects Collection Compiled 1969 - Revised 2002 Works Progress Administration (WPA) Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Project Collection. Records, 1937–1941. 23 feet. Federal project. Book-length manuscripts, research and project reports (1937–1941) and administrative records (1937–1941) generated by the WPA Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ projects for Oklahoma during the 1930s. Arranged by county and by subject, these project files reflect the WPA research and findings regarding birthplaces and homes of prominent Oklahomans, cemeteries and burial sites, churches, missions and schools, cities, towns, and post offices, ghost towns, roads and trails, stagecoaches and stage lines, and Indians of North America in Oklahoma, including agencies and reservations, treaties, tribal government centers, councils and meetings, chiefs and leaders, judicial centers, jails and prisons, stomp grounds, ceremonial rites and dances, and settlements and villages. Also included are reports regarding geographical features and regions of Oklahoma, arranged by name, including caverns, mountains, rivers, springs and prairies, ranches, ruins and antiquities, bridges, crossings and ferries, battlefields, soil and mineral conservation, state parks, and land runs. In addition, there are reports regarding biographies of prominent Oklahomans, business enterprises and industries, judicial centers, Masonic (freemason) orders, banks and banking, trading posts and stores, military posts and camps, and transcripts of interviews conducted with oil field workers regarding the petroleum industry in Oklahoma. ____________________ Oklahoma Box 1 County sites – copy of historical sites in the counties Adair through Cherokee Folder 1. Adair 2. Alfalfa 3. Atoka 4. Beaver 5. Beckham 6. -

These Hills, This Trail: Cherokee Outdoor Historical Drama and The

THESE HILLS, THIS TRAIL: CHEROKEE OUTDOOR HISTORICAL DRAMA AND THE POWER OF CHANGE/CHANGE OF POWER by CHARLES ADRON FARRIS III (Under the Direction of Marla Carlson and Jace Weaver) ABSTRACT This dissertation compares the historical development of the Cherokee Historical Association’s (CHA) Unto These Hills (1950) in Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Cherokee Heritage Center’s (CHC) The Trail of Tears (1968) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears were originally commissioned to commemorate the survivability of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and the Cherokee Nation (CN) in light of nineteenth- century Euramerican acts of deracination and transculturation. Kermit Hunter, a white southern American playwright, wrote both dramas to attract tourists to the locations of two of America’s greatest events. Hunter’s scripts are littered, however, with misleading historical narratives that tend to indulge Euramerican jingoistic sympathies rather than commemorate the Cherokees’ survivability. It wasn’t until 2006/1995 that the CHA in North Carolina and the CHC in Oklahoma proactively shelved Hunter’s dramas, replacing them with historically “accurate” and culturally sensitive versions. Since the initial shelving of Hunter’s scripts, Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears have undergone substantial changes, almost on a yearly basis. Artists have worked to correct the romanticized notions of Cherokee-Euramerican history in the dramas, replacing problematic information with more accurate and culturally specific material. Such modification has been and continues to be a tricky endeavor: the process of improvement has triggered mixed reviews from touristic audiences and from within Cherokee communities themselves. -

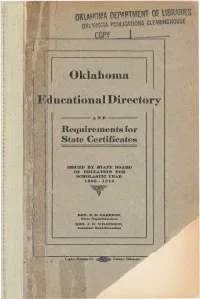

Oklahoma Mdideational Directory

OKI AFOMA OEPftfOMEHT OF UBRM8ES Itwi Pti3UC/vnONS CLEARINGHOUSE COPY I— Oklahoma Mdideational Directory AND Requirements for State Certificates ISSUED BY STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR SCHOLASTIC YEAR 1909 - 1910 HON. E. D. CAMERON, State Superintendent HON. J. W. WILKINSON, Assistant Superintendent Leadey Prising Co. Guthrie, Oklahoma k ^ OKLAHOMA ^ EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY AND REQUIREMENTS FOR STATE CERTIFICATES j ISSUED BY STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION FOR THE SCHOLASTIC YEAR 1909- 1910 HON. E. D. CAMERON, State Superintendent HON. J. W. WILKINSON, Assistant Superintendent } EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY. List of Territorial Superintendents of Public Instruction in Order of Appointment. Number. Superintendent. 1 J. H. Lawhead 2 J. H. Parker 3 E. D. Cameron 4 Albert O. Nichols 5 S. N. Hopkins 6 L. W. Baxter 7 J. E. Dyche List of State Superintendents of Public Instruction in Order of Election. 1. E. D. Cameron, First 'State Superintendent—Elected September 17, 1907—Term expires January, 1911. State Board of Education. E. D. Cameron State Superintendent C. N. Haskell Governor Wm. Cross Secretary of State Charles West Attorney General Officers of the Board. E. D. Cameron President Wm. Cross Secretary State Department of Education. E. D. Cameron State Superintendent John W. Will inson Assistant Superintendent J. M. Osborn Examiner and Diploma Clerk O. P. Callahan Agricultural Asisistant Leon W. Wiley Chief Clerk D. B. Hamilton Stenographer 903 4 00 3$ .(TS'Ax ii HON, E. D. JAMERON, STATE SUPERINTENDENT. President of State Board of Education, Agricultural and Industrial Commission, Board of Regents for Normal Schools, Board of Regents for the Girls' Industrial School, Board of Regents of \ the Oklahoma School for the Deaf, Board of Regents for the Oklahoma School for the Blind, and Chairman of the State Board of Pardons, Member Board of Land Commissioners, Board of Regents C. -

Inculpados De Altruismo. Los Cherokees En El Siglo

-------- ANUARIO deiiEHS 11, Tandll, 1996 INCULPADOS DE A!;fRUISMO. LOS CHEROKEES EN EL SIGLO XIX * Ronald Wright Un motivo de la compra de la Louisiana por Estados Unidos fue precisamente adquirir un «desierto» al que la república pudiera expulsar a todos los indios que no asimilara y en 1808 se comenzó a presionar para que se trasladara toda la nación che rokee, sin el menor escrúpulo a la hora de utilizar el soborno y la amenaza cuando las promesas fracasaban. Alrededor de 2.000 cherokees, convencidos de que, de to dos modos, se les obligaría a abandonar sus hogares, se encaminaron al oeste, aun que la idea resultara odiosa a la mayoría. El oeste ofrecía la oportunidad de continuar con las costumbres ancestrales, pero Jos tradicionalistas, menos contaminados de aculturación, eran los más reacios a abandonar la tierra sagrada y las tumbas anti guas. Estos tradicionalistas no se habían beneficiado de la contrapartida por el paso a una economía euroamericana ni deseaban hacerlo. Explotar la tierra de aquella ma nera era blasfemo: los arados la abrían desgarrándola más despiadadamente que es carbando con palos, lo que la erosionaba, y la escasez de caza demostraba que el mundo se estaba muriendo. En 1811 sns temores se manifestaron en un culto llama do a veces la danza del fantasma cherokee, estmcturado por el sanador Tsali. El Creador, decía él, había hecho pueblos d-iferentes en tie1ras distintas; la presencia de los blancos en América era antinatural y equivocada. El Seiíor de la Vida nunca tu- * Esta entrega es un fragmento de Continentes robodos.