Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crisis and Adaptation (1884–1890S)

CHAPTER THREE CRISIS AND ADAPTATION (1884–1890S) In 1870 the Cultivation System was officially abolished and private enter- prise was allowed to operate more freely. However, tapping the wealth of the Indonesian archipelago proved difficult. The crisis of November 1884 had far reaching consequences for the business world of the Netherlands Indies, and involved some of the largest companies around such as Dorrepaal & Co. Business interests in Amsterdam – together with the NHM and DJB – intervened and prevented a full-fledged collapse of the private economic sector. The threatening credit crunch could only be solved by an overhaul of the customs regarding credit extension which came down to financing long-term investments by incurring short- term debts. The 1884 crisis exposed the shaky foundations of the private economy. Many firms were forced to adjust their business strategy accordingly. The ties between commerce and capital became better guarded. The comple- tion of this painful reorganization constituted a fundamental reassess- ment of the relationship between capital, commerce and agricultural enterprise. The crisis also affected the spending power of the indigenous population with great repercussions for the import side of the economy. Chinese and European enterprise with their mutual linkages suffered accordingly. Many Chinese tradesmen defaulted to the detriment of their predominantly European creditors. Economic Policy and Political Expansion The post-1870 liberal attitude governing economic policy would consti- tute the rather loose framework of entrepreneurial conduct until the eco- nomic crisis of the 1930s. In a political sense abstention was the official ideology behind Dutch colonial economic policy ever since 1841. Given the limited resources of the Dutch state, the country’s colonial posses- sions were to be confined to Java. -

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder & Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Stichting beheer IISG Amsterdam 2012 2012 Stichting beheer IISG, Amsterdam. Creative Commons License: The texts in this guide are licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 license. This means, everyone is free to use, share, or remix the pages so licensed, under certain conditions. The conditions are: you must attribute the International Institute of Social History for the used material and mention the source url. You may not use it for commercial purposes. Exceptions: All audiovisual material. Use is subjected to copyright law. Typesetting: Eef Vermeij All photos & illustrations from the Collections of IISH. Photos on front/backcover, page 6, 20, 94, 120, 92, 139, 185 by Eef Vermeij. Coverphoto: Informal labour in the streets of Bangkok (2011). Contents Introduction 7 Survey of the Asian archives and collections at the IISH 1. Persons 19 2. Organizations 93 3. Documentation Collections 171 4. Image and Sound Section 177 Index 203 Office of the Socialist Party (Lahore, Pakistan) GUIDE TO THE ASIAN COLLECTIONS AT THE IISH / 7 Introduction Which Asian collections are at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam? This guide offers a preliminary answer to that question. It presents a rough survey of all collections with a substantial Asian interest and aims to direct researchers toward historical material on Asia, both in ostensibly Asian collections and in many others. -

Sexuality and Power

The Newsletter | No.54 | Summer 2010 12 The Study Sexuality and power A very Dutch view of the ‘submission’ of the Javanese – Nicolaas Pieneman’s (1809-1860) portrait of Dipanagara’s capture at Magelang on 28 March 1830 entitled ‘De onder- werping van Diepo Negoro aan Luitenant- Generaal De Kock, 28 Maart 1830’ (1833). Photograph courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. ‘All Java knows this – how the Dutch allowed the kraton [of Yogyakarta] to be turned into a brothel and how [Prince] Dipanagara [1785-1855] has sworn to destroy it to the last stone’.1 Peter Carey Below: The mystic prince and his family. THE WORDS OF THE LEIDEN laWYER, Willem van Hogendorp a torrent of abuse against the Dutch officials of the pre-war Coloured drawing of Dipanagara in exile (1795-1838), then serving as a legal adviser to Commissioner- period and their inability to speak anything but market Malay, in Makassar (1833-55) reading a text on General L.P.J. du Bus de Gisignies (in office, 1826-1830), could complaining that ‘Chevallier [P.F.H. Chevallier, Assistant- Islamic mysticism (tasawwuf) accompanied not have been more blunt. Writing to his father Gijsbert Karel Resident of Yogyakarta, 1795-1825, in office, 1823-1825] and by his wife, Radèn Ayu Retnaningsih, and (1762-1834) during the second year of the Java War (1825-30), other Dutchmen had trotted into our [Yogyakarta] kraton as one of his sons, ‘Pangéran Ali Basah’, the 32-year-old Willem confided that the liberties that the though it was a stable and had shouted and called as though it who is having a vision of a Javanese spirit. -

Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Indonesian Cities – a Policy Note

SEPTEMBER 2019 STRENGTHENING THE Public Disclosure Authorized DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Background Urbanization Time to ACT: Realizing Paper Flagship Report Indonesia’s Urban Potential Public Disclosure Authorized STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Urban floods have significant impacts on the livelihoods and mobility of Indonesians, affecting access to employment opportunities and disrupting local economies. (photos: Dani Daniar, Jakarta) Acknowledgement This note was prepared by World Bank staff and consultants as input into the Bank’s Indonesia Urbanization Flagship report, Time to ACT: Realizing Indonesia’s Urban Potential, which can be accessed here: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31304. The World Bank team was led by Jolanta Kryspin-Watson, Lead Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Jian Vun, Infrastructure Specialist, Zuzana Stanton-Geddes, Disaster Risk Management Specialist, and Gian Sandosh Semadeni, Disaster Risk Management Consultant. The paper was peer reviewed by World Bank staff including Alanna Simpson, Senior Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Abigail Baca, Senior Financial Officer, and Brenden Jongman, Young Professional. The background work, including technical analysis of flood risk, for this report received financial support from the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) through the World Bank Indonesia Sustainable Urbanization (IDSUN) Multi-Donor Trust Fund. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. ii STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE THE WORLD BANK Table of Contents 1. -

Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Jurnal Psikologi Volume 44, Nomor 1, 2017: 66 - 79 DOI: 10.22146/jpsi.26898 Parental Expectations and Young People’s Migratory Experiences in Indonesia Wenty Marina Minza1 Center for Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada Abstract. Based on a one-year qualitative study, this paper examines the migratory aspirations and experiences of non-Chinese young people in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. It is based on two main questions of migration in the context of young people’s education to work transition: 1) How do young people in provincial cities perceive processes of migration? 2) What is the role of intergenerational relations in realizing these aspirations? This paper will describe the various strategies young people employ to realize their dreams of obtaining education in Java, the decisions made by those who fail to do so, and the choices made by migrants after the completion of their education in Java. It will contribute to a body of knowledge on young people’s education to work transitions and how inter-generational dynamics play out in that process. Keywords: intergenerational relation; migratory aspiration; youth Internal1 migration plays a key role in older generation in Pontianak generally mapping mobility patterns among young associate Java with ideas of progress, people, as many young people continue to opportunities for social mobility, and the migrate within their home country (Argent success of inter-generational reproduction & Walmsley, 2008). Indonesia is no excep- or regeneration. Yet, migration involves tion. The highest participation of rural various negotiation processes that go urban migration in Indonesia is among beyond an analysis of push and pull young people under the age of 29, mostly factors. -

SCHEDULE WEEK#03.Xlsx

WEEK03 NEW CMI SERVICE : SEMARANG - SURABAYA - MAKASSAR - BATANGAS - WENZHOU - SHANGHAI - XIAMEN - SHEKOU - NANSHA- HO CHI MINH ETD ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA ETA VESSEL VOY SEMARANG SURABAYA MAKASSAR BATANGAS Wenzhou SHANGHAI XIAMEN SHEKOU NANSHA HOCHIMINH SITC SEMARANG 2103N 16‐Jan 17‐Jan 19‐Jan 23‐Jan SKIP 28‐Jan 31‐Jan 1‐Feb 2‐Feb 6‐Feb SITC ULSAN 2103N 22‐Jan 23‐Jan 25‐Jan 29‐Jan SKIP 3‐Feb 6‐Feb 7‐Feb 8‐Feb 12‐Feb SITC SHEKOU 2103N 29‐Jan 30‐Jan 1‐Feb 5‐Feb SKIP 10‐Feb 13‐Feb 14‐Feb 15‐Feb 19‐Feb SITC SURABAYA 2103N 5‐Feb 6‐Feb 8‐Feb 12‐Feb SKIP 17‐Feb 20‐Feb 21‐Feb 22‐Feb 26‐Feb SITC SEMARANG 2105N 12‐Feb 13‐Feb 15‐Feb 19‐Feb SKIP 24‐Feb 27‐Feb 28‐Feb 1‐Mar 5‐Mar ** Schedule, Estimated Connecting Vessel, and open closing time are subject to change with or without prior Notice ** WE ALSO ACCEPT CARGO EX : For Booking & Inquiries, Please Contact : Jayapura,Sorong,Bitung,Gorontalo,Pantoloan,Banjarmasin,Samarinda,Balikpapan Customer Service and Outbound Document: ***Transship MAKASSAR Panji / [email protected] / +62 85225501841 / PHONE: 024‐8316699 From Padang,Palembang,Panjang,Pontianak,Banjarmasin,Samarinda,Balikpapan Mey / [email protected] / +62 8222 6645 667 / PHONE : 024 8456433 ***Transship JAKARTA From Pontianak Marketing: ***Transship SEMARANG Lindu / [email protected] / +62 81325733413 / PHONE: 024‐8447797 Equipment & Inbound Document: ALSO ACCEPT CARGO TO DEST : Ganda / [email protected] /+62 81329124361 / Phone : 024‐8315599 Haikou/Fuzhou/Putian/Shantou TRANSSHIP XIAMEN BY FEEDER Keelung/Taichung/Kaohsiung TRANSSHIP SHANGHAI BY FEEDER Finance: Lianyungang, Zhapu Transship Ningbo BY FEEDER Tuti / [email protected] / Phone : 024‐8414150 Fangcheng/Qinzhou TRANSSHIP SHEKOU BY FEEDER HEAD OFFICE : SURABAYA BRANCH : SITE OFFICE : PONTIANAK AGENT Gama Tower, 36th Floor Unit A B C Jembatan Merah Arcade Building 2nd Floor Jln .Gorontalo 3 No.3‐5 PT. -

Decolonization of the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia

Europeans and decolonisations Decolonization of the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia Pieter EMMER ABSTRACT Japan served as an example for the growing number of nationalists in the Dutch East Indies. In order to pacify this group, the Dutch colonial authorities instituted village councils to which Indonesians could be elected, and in 1918 even a national parliament, but the Dutch governor-general could annul its decisions. Many Dutch politicians did not take the unilateral declaration of independence of August 1945 after the ending of the Japanese occupation seriously. Because of this stubbornness, a decolonization war raged for four years. Due to pressures from Washington the Dutch government agreed to transfer the sovereignty to the nationalists in 1949 as the Americans threatened to cut off Marshall aid to the Netherlands. The Dutch part of New Guinea was excluded from the transfer, but in 1963 again with American mediation the last remaining part of the Dutch colonial empire in Asia was also transferred to Indonesian rule. A woman internee at Tjideng camp (Batavia), during the Japanese occupation, in 1945. Source : Archives nationales néerlandaises. Inscription on a wall of Purkowerto (Java), July 24th 1948. Source : Archives nationales néerlandaises. Moluccan soldiers arrive in Rotterdam with their families, on March 22nd 1951. Source : Wikipédia The Dutch attitude towards the independence movements in the Dutch East Indies Modern Indonesian nationalism was different from the earlier protest movements such as the Java War (1825-1830) and various other forms of agrarian unrest. The nationalism of the Western-educated elite no longer wanted to redress local grievances, but to unite all Indonesians in a nation independent of Dutch rule. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Captures Asean

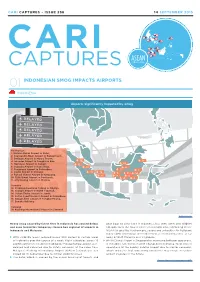

CARI CAPTURES • ISSUE 236 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 CARI ASEAN CAPTURES REGIONAL 01 INDONESIAN SMOG IMPACTS AIRPORTS INDONESIA Airports Significantly Impacted by Smog DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED Kalimantan 1. Melalan Melak Airport in Kutai, 2. Syansyudin Noor Airport in Banjarmasin, 3. Beringin Airport in Muara Teweh, 4. Iskandar Airport in Pangkalan Bun 13 11 5. Haji Asan Airport in Sampit, 12 18 6. Supadio Airport in Kubu Raya, 14 8 7. Pangsuma Airport in Putussibau, 7 1 8. Susilo Airport in Sintang, 15 16 6 3 10 9. Rahadi Usman Airport in Ketapang, 17 9 5 10. Tjilik Riwut Airport in Pontianak, 4 2 11. Atty Besing Airport in Malinau. Sumatra 12. Ferdinand Lumban Tobing in Sibolga, 13. Silangit Airport in North Tapanuli, 14. Sultan Thaha Airport in Jambi, 15. Sultan Syarif Kasim II Airport in Pekanbaru, 16. Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang, 17. Bangka Belitung Sarawak 18. Kuching International Airport in Sarawak Antara News Heavy smog caused by forest fires in Indonesia has caused delays peat bogs to clear land in Indonesia, has seen some 400 wildfire and even forced the temporary closure two regional of airports in hotspots over the course of the past month alone according to the Indonesia and Malaysia. NOAA-18 satellite; furthermore, severe and unhealthy Air Pollutant Index (API) recordings were observed at several locations as far With visibility levels reduced below 800 meters in certain areas away as East Malaysia and Singapore of Indonesia over the course of a week, flight schedules across 16 Whilst Changi Airport in Singapore -

Laporan Kinerja Badan Geologi Tahun 2014

LAPORAN KINERJA BADAN GEOLOGI TAHUN 2014 BADAN GEOLOGI KEMENTERIAN ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL Tim Penyusun: Oman Abdurahman - Priatna - Sofyan Suwardi (Ivan) - Rian Koswara - Nana Suwarna - Rusmanto - Bunyamin - Fera Damayanti - Gunawan - Riantini - Rima Dwijayanti - Wiguna - Budi Kurnia - Atep Kurnia - Willy Adibrata - Fatmah Ughi - Intan Indriasari - Ahmad Nugraha - Nukyferi - Nia Kurnia - M. Iqbal - Ivan Verdian - Dedy Hadiyat - Ari Astuti - Sri Kadarilah - Agus Sayekti - Wawan Bayu S - Irwana Yudianto - Ayi Wahyu P - Triyono - Wawan Irawan - Wuri Darmawati - Ceme - Titik Wulandari - Nungky Dwi Hapsari - Tri Swarno Hadi Diterbitkan Tahun 2015 Badan Geologi Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Jl. Diponegoro No. 57 Bandung 40122 www.bgl.esdm.go.id Pengantar Geologi merupakan salah satu pendukung penting dalam program pembangunan nasional. Untuk program tersebut, geologi menyediakan informasi hulu di bidang En- ergi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (ESDM). Di samping itu, kegiatan bidang geologi juga menyediakan data dan informasi yang diperlukan oleh berbagai sektor, seperti mitigasi bencana gunung api, gerakan tanah, gempa bumi, dan tsunami; penataan ruang, pemba- ngunan infrastruktur, pengembangan wilayah, pengelolaan air tanah, dan penyediaan air bersih dari air tanah. Pada praktiknya, pembangunan kegeologian di tahun 2014 masih menghadapi beber- apa isu strategis berupa peningkatan kualitas hidup masyarakat Indonesia mencapai ke- hidupan yang sejahtera, aman, dan nyaman mencakup ketahanan energi, lingkungan dan perubahan iklim, bencana alam, tata ruang dan pengembangan wilayah, industri mineral, pengembangan informasi geologi, air dan lingkungan, pangan, dan batas wilayah NKRI (kawasan perbatasan dan pulau-pulau terluar). Ketahanan energi menjadi isu utama yang dihadapi sektor ESDM, sekaligus menjadi yang dihadapi oleh Badan Geologi yang mer- upakan salah satu pendukung utama bagi upaya-upaya sektor ESDM. -

The Indonesian Struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949

The Indonesian struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949 Excessive violence examined University of Amsterdam Bastiaan van den Akker Student number: 11305061 MA Holocaust and Genocide Studies Date: 28-01-2021 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ugur Ümit Üngör Second Reader: Dr. Hinke Piersma Abstract The pursuit of a free Indonesian state was already present during Dutch rule. The Japanese occupation and subsequent years ensured that this pursuit could become a reality. This thesis examines the last 4 years of the Indonesian struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949. Excessive violence prevailed during these years, both the Indonesians and the Dutch refused to relinquish hegemony on the archipelago resulting in around 160,000 casualties. The Dutch tried to forget the war of Indonesian Independence in the following years. However, whistleblowers went public in the 1960’s, resulting in further examination into the excessive violence. Eventually, the Netherlands seems to have come to terms with its own past since the first formal apologies by a Dutch representative have been made in 2005. King Willem-Alexander made a formal apology on behalf of the Crown in 2020. However, high- school education is still lacking in educating students on these sensitive topics. This thesis also discusses the postwar years and the public debate on excessive violence committed by both sides. The goal of this thesis is to inform the public of the excessive violence committed by Dutch and Indonesian soldiers during the Indonesian struggle for Independence. 1 Index Introduction -

6 Intersecting Spheres of Legality and Illegality | Considered Legitimate by Border Communities Back in Control of Their Traditional Forests

6 Intersecting spheres of legality and illegality For those living in the borderland, it is a zone unto itself, neither wholly subject to the laws of states nor completely independent of them. Their autonomous practices make border residents and their cross-border cul- tures a zone of suspicion and surveillance; the visibility of the military and border forces an index of official anxiety (Abraham 2006:4). Borderland lawlessness, or the ‘twilight zone’ between state law and au- thority, often provides fertile ground for activities deemed illicit by one or both states – smuggling, for example. Donnan and Wilson (1999) note how borders can be both ‘used’ (by trade) and ‘abused’ (by smuggling) concur with Van Schendel’s claim that ‘[t]he very existence of smuggling undermines the image of the state as a unitary organization enforcing law and order within clearly defined territory’ (1993:189). This is espe- cially true along the remote, rugged and porous borders of Southeast Asia where the smuggling of cross-border contraband has a deep-rooted history (Tagliacozzo 2001, 2002, 2005). As noted in Chapters 3, 4 and 5, illegal trade or smuggling (semukil) of various contraband items back and forth across the West Kalimantan- Sarawak border has been a continuous concern of Dutch and Indonesian central governments ever since the establishment of the border. Drawn by the peculiar economic and social geography, several scholars men- tion how borderlands often attract opportunistic entrepreneurs. They also mention how such border zones may promote the growth of local leadership built on illegal activities and maintained through patronage, violence and collusion.1 Alfred McCoy asserts that the presence of such local leadership at the edges of Southeast Asian states is a significant 1 Gallant 1999; McCoy 1999; Van Schendel 2005; Sturgeon 2005; Walker 1999.