The Ghost Sonata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romantic and Realistic Impulses in the Dramas of August Strindberg

Romantic and realistic impulses in the dramas of August Strindberg Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Dinken, Barney Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 13:12:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557865 ROMANTIC AND REALISTIC IMPULSES IN THE DRAMAS OF AUGUST STRINDBERG by Barney Michael Dinken A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF DRAMA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fu lfillm e n t of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available,to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests fo r permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship, In a ll other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's a Dream Play

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses October 2018 Interpreting Dreams: Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's A Dream Play Mary-Corinne Miller University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Mary-Corinne, "Interpreting Dreams: Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's A Dream Play" (2018). Masters Theses. 730. https://doi.org/10.7275/12087874 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/730 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETING DREAMS: DIRECTING AN IMMERSIVE ADAPTATION OF STRINDBERG’S A DREAM PLAY A Thesis Presented By MARY CORINNE MILLER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS September 2018 Department of Theater © Copyright by Mary Corinne Miller 2018 All Rights Reserved INTERPRETING DREAMS: DIRECTING AN IMMERSIVE ADAPTATION OF STRINDBERG’S A DREAM PLAY A Thesis Presented By MARY CORINNE MILLER Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ Gina Kaufmann, Chair ____________________________________ Harley Erdman, Member ____________________________________ Gilbert McCauley, Member ____________________________________ Amy Altadonna, Member ____________________________ Gina Kaufmann, Department Head Department of Theater DEDICATION To my son, Everett You are my dream come true. -

Miss Julie by August Strindberg

MTC Education Teachers’ Notes 2016 Miss Julie by August Strindberg – PART A – 16 April – 21 May Southbank Theatre, The Sumner Notes prepared by Meg Upton 1 Teachers’ Notes for Miss Julie PART A – CONTEXTS AND CONVERSATIONS Theatre can be defined as a performative art form, culturally situated, ephemeral and temporary in nature, presented to an audience in a particular time, particular cultural context and in a particular location – Anthony Jackson (2007). Because theatre is an ephemeral art form – here in one moment, gone in the next – and contemporary theatre making has become more complex, Part A of the Miss Julie Teachers’ Notes offers teachers and students a rich and detailed introduction to the play in order to prepare for seeing the MTC production – possibly only once. Welcome to our new two-part Teachers’ Notes. In this first part of the resource we offer you ways to think about the world of the play, playwright, structure, theatrical styles, stagecraft, contexts – historical, cultural, social, philosophical, and political, characters, and previous productions. These are prompts only. We encourage you to read the play – the original translation in the first instance and then the new adaptation when it is available on the first day of rehearsal. Just before the production opens in April, Part B of the education resource will be available, providing images, interviews, and detailed analysis questions that relate to the Unit 3 performance analysis task. Why are you studying Miss Julie? The extract below from the Theatre Studies Study Design is a reminder of the Key Knowledge required and the Key Skills you need to demonstrate in your analysis of the play. -

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Edited by Roland Lysell Strindberg on International Stages/Strindberg in Translation, Edited by Roland Lysell This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Roland Lysell and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5440-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5440-5 CONTENTS Contributors ............................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Section I The Theatrical Ideas of August Strindberg Reflected in His Plays ........... 11 Katerina Petrovska–Kuzmanova Stockholm University Strindberg Corpus: Content and Possibilities ........ 21 Kristina Nilsson Björkenstam, Sofia Gustafsson-Vapková and Mats Wirén The Legacy of Strindberg Translations: Le Plaidoyer d'un fou as a Case in Point ....................................................................................... 41 Alexander Künzli and Gunnel Engwall Metatheatrical -

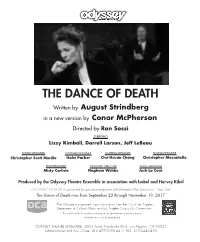

THE DANCE of DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a New Version by Conor Mcpherson Directed by Ron Sossi

THE DANCE OF DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a new version by Conor McPherson Directed by Ron Sossi STARRING Lizzy Kimball, Darrell Larson, Jeff LeBeau SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Christopher Scott Murillo Halei Parker Chu-Hsuan Chang Christopher Moscatiello PROP DESIGNER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR STAGE MANAGER Misty Carlisle Nagham Wehbe Josh La Cour Produced by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in association with Isabel and Harvey Kibel THE DANCE OF DEATH is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service Inc., New York The Dance of Death runs from September 23 through November 19, 2017 The Odyssey is supported in part by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs, and Los Angeles County Arts Commission The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE: 2055 South Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025 Administration and Box Office: 310-477-2055 ext 2 FAX: 310-444-0455 CAST (in order of appearance) THE CAPTAIN .................................................................Darrell Larson ALICE .............................................................................Lizzy Kimball KURT .................................................................................Jeff LeBeau SETTING An Island Fortress near a port in Sweden, Early 20th Century Running time: Two hours There will be one fifteen-minute intermission. This production is dedicated to Sam Shepard. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Dance of Death has amazing significance to the whole world of contemporary drama. The "trapped" nature of its characters feels like Sartre's No Exit (and its classic line "Hell is other people"). And its foreshadow- ing of Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is uncannily prescient, almost as if Albee "channeled" Strindberg in cooking up his own mixture of raucous verbal battle and deadly humor. -

Bibliographie Der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020)

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014– 2020) 2020 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Westerkappeln: DerWulff.de 2020 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197, 2020: Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek. ISSN 2366-6404. URL: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Letzte Änderung: 19.10.2020. Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020) Zusammengestell !on "ans #$ %ul& und 'udger (aczmarek Mit der folgenden Bibliographie stellen wir unseren Leser_innen die zweite Fortschrei- bung der „Bibliographie der Filmmusik“ vor die wir !""# in Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere $#% !""#& 'rgänzung )* +,% !"+-. begr/ndet haben. 1owohl dieser s2noptische 3berblick wie auch diverse Bibliographien und Filmographien zu 1pezialproblemen der Filmmusikforschung zeigen, wie zentral das Feld inzwischen als 4eildisziplin der Musik- wissenscha5 am 6ande der Medienwissenschaft mit 3bergängen in ein eigenes Feld der Sound Studies geworden ist. -

A Director's Approach to Ingmar Bergman's Nora Cason Warinner

ABSTRACT Opening the Door: A Director’s Approach to Ingmar Bergman’s Nora Cason Warinner Murphy, M.F.A. Thesis Chairperson: Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D. In 1981, Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman radically adapted Henrik Ibsen’s classic stageplay A Doll’s House in order to create his own theatrical work, Nora. Through cutting much of Ibsen’s text and many of his characters, Bergman focused his adaptation on the figure of Nora Helmer, a naïve 19th-century wife and mother desperately trying to avoid the consequences of her past actions. This thesis examines the process undertaken in bringing Bergman’s play to its November 2015 performance run at Baylor University, with explorations of playwright and playscript histories, of directorial analysis and production concepts, and the creative collaborations established between director, designers, and actors. Opening the Door: A Director's Approach to Ingmar Bergman's Nora by Cason Warinner Murphy, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Theatre Arts Stan C. Denman, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D., Chairperson DeAnna M. Toten Beard, M.F.A., Ph.D. Stan C. Denman, Ph.D. David J. Jortner, Ph.D. James Kendrick, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2016 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2016 by Cason Warinner Murphy All rights reserved TABLE -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations CULTURAL CO-ORDINATES AND RUMINATIONS: A STUDY OF CARYL CHURCHILL’S ADAPTATION OF STRINDBERG’S THE DREAM PLAY PINKY ISHA Guest lecturer Indira Gandhi National Open University, Kolkata (W.B.) ABSTRACT Strindberg the very famous Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist and painter was an extremely prolific writer whose literary career spans more than half a century in which he experimented with a range of literary styles, indicating his preference for naturalism, tragedy, melodrama, expressionism and surrealism as well as a keen insight into the genre of the unconscious. The preoccupation with memory, the funny yet threatening responses of individuals and groups, also form and control the thematic world of one of the most noteworthy postmodern female British playwright, Caryl Churchill. Known as an iconoclastic writer, Churchill’s adaptation of Strindberg’s The Dream Play is bold, strikingly modern and very concise. In fact it is more challenging in scope and dramatic form. The focus of this paper is an in-depth analysis of both playwrights’ technicalities and stylistic devices in The Dream Play which will help explain the play’s contemporaneity and significance even today. (Words: 150) Keywords: memory, unconscious, Hindu mysticism, surrealism, disintegration, expressionism. Theatre as a medium for literary and artistic expression through performance is the oldest and the most challenging form of social and cultural documentation of an era or a nation. The theatre of Athens produced Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes. Elizabethan England produced Marlowe, Shakespeare, Johnson and many more literary geniuses. -

A Dream Play, Directed by Robert Wilson

Btooklyn 3CJ l c-Jf;wette Avenue Communications Department Academy f~rooklvr f\!Y ll 21 I -l4uo [ IPtkl r ark of lelepl1on~. 718.036 Llll 1 rv1elrS~d CtJSICk Music Fdx !lt..8~>7 ?O?l !\my I i ugi1CS larnnra McCaw Kila Packett 71863G.4129 News Release BAM's 2000 Next Wave Festival Presents the U.S. Premiere of Stadsteater (Stockholm)'s Production of A Dream Play, Directed by Robert Wilson Production marks Wilson's first exploration of an August Strindberg work Written by August Strindberg Stockholm's Stadsteater Direction, design, and lighting by Robert Wilson Co-direction by Ann-Christin Rommen Music by Michael Galasso Costumes and masks by Jacques Reynaud Lighting by Andreas Fuchs and Robert Wilson Dramaturgy by Holm Keller and Monica Ohlsson Sound by Ronald Hallgren BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Nov 28- Dec 2 at 7:30pm and Dec 3 at 3pm Tickets: $20, 35, 55 Performed in Swedish with English surtitles BAMcafe Live presents A Dream Play n1usic composer Michael Galasso (violin) Friday, November 24 at 9pm BROOKLYN, November 3, 2000- Acclaimed director, designer, and installation 0 artist Robert Wilson returns to BAM's Next Wave Festival with his highly-praised interpretation of August Strindberg's A Dream Play-a U.S. premiere production that 0 has inspired glowing reviews in Europe and Australia. Collaborating with Stockholm's Stadsteater, Wilson creates a stunning version that re-orders time, space, and narrative. 0 The production marks the artist's first staging of a Strindberg work, nearly a century N • more ... ave 2oDO -- \ \ _ o:s - c\Yu\~ _ pl _ pr <- _ r-e\e~ A Dream Play 2 after it was written. -

Of the Royal Family Resided Mainly on the First Floor

4 of Kings •srmatio on Berna and evolu MIKAEL ALM & BRITT-INGER JOHANSSON (EDS.) Opuscula Historica Upsaliensia utges av Historiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet och syftar till att sprida information om den forskning som bedrivs vid och i anslutning till institutionen. Huvudredaktör: Mikael Alm Redaktion: Josefin Englund, Jonas Lindström, Cristina Prytz och Patrik Winton. Löpande prenumeration tecknas genom skriftlig anmälan till Opuscula, Historiska institutionen, Box 628, 751 26 Uppsala, [email protected], http://www.hist.uu.se/opuscula/ Enstaka nummer kan beställas från Swedish Science Press, Box 118, 751 04 Uppsala, www.ssp.nu, [email protected], telefon 018/36 55 66, telefax 018/36 52 77 Scripts of Kingship Essays on Bernadotte and Dynastic Formation in an Age of Revolution MIKAEL ALM & BRITT-INGER JOHANSSON (EDS.) Distribution Swedish Science Press, Box 118, 751 04 Uppsala [email protected], www.ssp.nu Cover illustration: Pehr Krafft (the Younger), The Coronation of Charles XIVJohn in Stockholm 1818 (detail). Nationalmuseum. Photo: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. © The authors Graphic design: Elina Antell Print: Reklam & katalogtryck AB, Uppsala 2008 ISSN 0284-8783 ISBN 978-91-977312-2-5 Editors' Preface The following nine essays emanate from the interdisciplinary project The Making of a Dynasty (Sw: En dynasti blir till. Medier, myter och makt kring Karl XIV Johan), financed by The Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation and directed by Nils Ekedahl. The introduction by Solfrid Söderlind is written specifically for this book, and Torkel Janssons contribution is an elaborated version of a previously published artide. The remaining seven essays were all presented as conference papers at the European Social Science and History Conference (ESSHC) in Amsterdam in March 2006. -

Strindberg Acrossborders Low.Pdf

Strindberg across Borders edited by Massimo Ciaravolo © 2016 Copyright Istituto Italiano Studi Germanici Via Calandrelli, 25 – 00153 Roma The volume has been published with the contribution of The King Gustaf VI Adolf Foundation for Swedish Culture (Stiftelsen Konung Gustaf VI Adolfs fond för svensk kultur) and the patronage of: Associazione Culturale di Scandinavistica Milano Firenze ISBN: 978-88-95868-20-2 Strindberg across Borders edited by Massimo Ciaravolo Table of Contents 5 Acknowledgements 7 Massimo Ciaravolo, Introduction WORLD LITERATURE 15 Vera Gancheva, August Strindberg – The Phoenix 31 Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams, Constructing Strindberg’s Life across Borders and Times TRANSLATION 41 Elisabeth Tegelberg, En Strindbergessä i kontrastiv belysning 63 Alexander Künzli and Gunnel Engwall, Strindberg and Transna tionality: The Case of Le Plaidoyer d’un fou GENDER, POLITICS AND SCIENCE 83 Tobias Dahlkvist, Strindberg som vansinnigt geni. Strindberg, Lom broso och frågan om geniets patologi 93 Massimo Ciaravolo, Between Literature and Politics. Strindberg and Scandinavian Radicalism as Seen through his Relationship with Edvard Brandes, Branting and Bjørnson 125 Cecilia Carlander, Strindberg och det androgyna O UTWARD AND INWARD, LOWER AND UPPER REALITY 139 Annie Bourguignon, Var går gränsen mellan jaget och makterna? 151 Deimantė Dementavičiūtė-Stankuvienė, Across Dream: Archety pical Images in Strindberg’s Dream Plays 163 Polina Lisovskaya, Christmas Eve in Strindberg’s Oeuvre 4 Table of Contents 179 Astrid Regnell, Konstens verklighet i En blå bok FORMS OF INTERTEXTUALITY 191 Maria Cristina Lombardi, Grotti and Loki: Two Mythological Be ings in Strindberg’s Literary Production 207 Andreas Wahlberg, Början i moll och finalen i dur. Om överträdan det av den osynliga gränsen i Strindbergs Ensam och Goethes Faust 219 Roland Lysell, Stora landsvägen som summering och metadrama 231 Martin Hellström, Strindberg for Children. -

A Dream Play Background Pack

Education A Dream Play Background Pack Contents A Dream Play 2 Introduction 3 The Original Play 4 The Director: Interview with Katie Mitchell 5 The Actor: Interview with Angus Wright 9 The Designer: Interview with Vicki Mortimer 12 Activities and Discussion 15 Related Materials 16 ADreamPlay By August Strindberg in a new version by Caryl Churchill with additional material by Katie Mitchell and the Company Angus Wright Photo: Stephen Cummiskey A Dream Play Background pack written by NT Education Background pack By August Strindberg, in a Jonathan Croall, journalist National Theatre © Jonathan Croall new version by Caryl Churchill and theatrical biographer, and South Bank The views expressed in this With additional material by author of three books in the London SE1 9PX background pack are not Katie Mitchell and the series ‘The National Theatre T 020 7452 3388 necessarily those of the Company. at Work’. F 020 7452 3380 National Theatre Director Editor E educationenquiries@ Katie Mitchell Emma Thirlwell nationaltheatre.org.uk Further production details Design www.nationaltheatre.org.uk Patrick Eley, Lisa Johnson A Dream Play CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) KATIE MITCHELL Director VICKI MORTIMER Designer MARK ARENDS CHRIS DAVEY Lighting Designer Young George, the broker’s brother KATE FLATT Choreographer Geoffrey, Victoria’s lover SIMON ALLEN Music Director and Arranger ANASTASIA HILLE CHRISTOPHER SHUTT Sound Designer Christine, the broker’s mother KATE GODFREY Company Voice Work KRISTIN HUTCHINSON Rachel, the broker’s first wife Music played live by: Paul Higgs Associate MD/piano/keyboard SEAN JACKSON Joe Townsend violin Security Supervisor Katja Mervola viola Port Health Officer Penny Bradshaw cello CHARLOTTE ROACH Schubert’s ‘Nacht und Träume’ specially Lina the maid recorded by: Ugly Edith, the broker’s co-respondent Mark Padmore tenor DOMINIC ROWAN Andrew West piano Herbert, the broker’s father Adult George, the broker’s brother This production opened at the National’s JUSTIN SALINGER Cottesloe Theatre on 15 February 2005.