Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Five Publishing the Private, Or the Economics of Experience

Chapter Five Publishing the Private, or The Economics of Experience Sometimes it has occurred to me that a man should not live more than he can record, as a farmer should not have a larger crop than he can gather in. – Boswell: The Hypochondriack Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person; this nobody has any right to but himself – Locke: Second Treatise on Civil Government I In a finely tempered and persuasive record of her encounters with Strindberg in Switzerland in 1884, Hélène Welinder recalls a conversation in which his young compatriot’s sympathetic concern prompted the tired and harassed writer to describe the condition of almost permanent literary production in which he lived with unusual clarity. ‘I cannot rest, even if I would like to,’ he is reported as saying: I have to write for my daily bread, to maintain my wife and children, and in other respects, too, I cannot leave it alone. If I am travelling by train or whatever I’m doing, my mind works without ceasing, it grinds and grinds like a mill, and I cannot stop it. I get no peace before I have put it down on paper, but then I begin all over again, and so the misery goes on.1 Whether or not the image of the remorseless and insatiable mill reached this quotation as a direct transcription of Strindberg’s words is, of course, open to question. Nevertheless, even if it belongs entirely to Welinder’s reconstruction, it is apposite, for it not only features frequently in Strindberg’s later work as an image for the treadmill of conscience and the tenacity with which the past clings to the present;2 it also encompasses the suggestion that to write out what experience provides affords at best only temporary relief. -

Dream and Life in Metamorphosis by Beijing Opera

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN(P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 4, Issue 3, Apr - May 2015, 9-14 © IASET DREAM AND LIFE IN METAMORPHOSIS BY BEIJING OPERA IRIS HSIN-CHUN TUAN Associate Professor, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan ABSTRACT Theatre has historically served as a space of dreaming, a place of escape or a retreat, a reflection of reality, and simulacra of existence. From Strindberg ( The Dream Play ), to Chuang-Tze (who has building his nice dream in jail to die one night before to escape from beheading ordered by the bad emperor the next morning), to Shakespeare ( AMidsummer Night’s Dream ), to Calderón ( Life is a Dream ), to Wu Hsing-Kuo( Metamorphosis ) to any of hundreds more, playwrights and directors have used the stage to make the ethereal, metaphysical and philosophical visible. Wu, Artistic Director and Lead Actor of The Contemporary Legend Theatre , theatrically adapts Franz Kafka’s short fiction Die Verwanglung (The Metamorphosis ) in which the protagonist wakes up from his dream to find out in shock that he becomes a big insect, and represents this story viare the atricalization. Wu’s solo performance (in which he plays multiple roles) in the Edinburgh International Festival in summer 2013 received considerable critical acclaims, reviews and TV interviews. In Metamorphosis (National Theater, Taipei, Dec. 2013), Wustages this whole story about the metamorphosed big insect by spectacular costume, performing in Beijing Opera, to manifest the metaphysical existential pain and meaning of life. As Wu’s highly praised Kingdom of Desire (adapted from Macbeth ) and Lear Is Here (adapted from King Lear ), we look forward to how Wu’s new work Metamorphosis represents the desert if no compassion. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

"Infidelity" As an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) As a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888)

"Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). مسـرحيــة After Miss Julie للكاتب البريطاني باتريك ماربر كإعادة إبداع لمسرحية Miss Julie للكاتب السويدي أوجست ستريندبرج Dr. Reda Shehata associate professor Department of English - Zagazig University د. رضا شحاته أستاذ مساعد بقسم اللغة اﻹنجليزية كلية اﻵداب - جامعة الزقازيق "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love" Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). Abstract Depending on Linda Hutcheon's notion of adaptation as "a creative and interpretative act of appropriation" and David Lane's concept of the updated "context of the story world in which the characters are placed," this paper undertakes a critical examination of Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a creative rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). The play appears to be both a faithful adaptation and appropriation of its model, reflecting "matches" for certain features of it and "mismatches" for others. So in spite of Marber's different language, his adjustment of the "temporal and spatial dimensions" of the original, and his several additions and omissions, he retains the same theme, characters, and—to a considerable extent, plot. To some extent, he manages to stick to his master's brand of Naturalism by retaining the special form of conflict upon which the action is based. In addition to its depiction of the failure of post-war class system, it shows strong relevancy to the spirit of the 1990s, both in its implicit critique of some aspects of feminism (especially its call for gender equality) and its bold address of the masculine concerns of that period. -

Conflicts of Interest in Financial Distress: the Role of Employees

International Journal of Economics and Finance; Vol. 9, No. 12; 2017 ISSN 1916-971X E-ISSN 1916-9728 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Conflicts of Interest in Financial Distress: The Role of Employees Wenchien Liu1 1 Department of Finance, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, R.O.C. Correspondence: Wenchien Liu, Department of Finance, Chung Yuan Christian University, 200 Chung Pei Road, Chung Li District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 32023, R.O.C. Tel: 886-3-265-5706. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 30, 2017 Accepted: October 25, 2017 Online Published: November 10, 2017 doi:10.5539/ijef.v9n12p101 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v9n12p101 Abstract The interests of employees are not consistent with those of other stakeholders when firms are in financial distress. Hence, conflicts of interest among stakeholders are more severe, especially for those firms with strong union power, as news is reported in the media. However, little attention has been paid to the impacts of employees on bankruptcy resolutions. This study examines the impacts of employees (i.e., union power) on the conflicts of interest of distressed firms in the United States from 1983 to 2015. We find that union power has strong effects on conflicts of interest related to employees, such as asset sales, debtor-in-possession financing, successful emergence from bankruptcy, and CEO replacement. On the contrary, for conflicts of interest unrelated to employees, including the choice of bankruptcy resolution method, and conflicts of interest between creditors and debtors, we find no significant relationships. Finally, we also find a positive impact of union power on the probability of refiling for bankruptcy in the future after emerging successfully. -

Romantic and Realistic Impulses in the Dramas of August Strindberg

Romantic and realistic impulses in the dramas of August Strindberg Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Dinken, Barney Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 13:12:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557865 ROMANTIC AND REALISTIC IMPULSES IN THE DRAMAS OF AUGUST STRINDBERG by Barney Michael Dinken A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF DRAMA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fu lfillm e n t of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available,to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests fo r permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship, In a ll other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Stockholm's Archipelago and Strindberg's

Scandinavica Vol 52 No 2 2013 Stockholm’s Archipelago and Strindberg’s: Historical Reality and Modern Myth-Making Massimo Ciaravolo University of Florence Abstract The Stockholm Archipelago is ubiquitous in the prose, poetry, drama and non-fiction of August Strindberg. This article examines the interaction in Strindberg’s oeuvre between the city of Stockholm as civilized space and the wild space surrounding it, tracing the development of a literary myth of Eden in his work. Strindberg’s representations of the shifting relations between city and nature, it is argued, played (and still play) an important role in the cultural construction of mythologies of the loss of the wild space. The environments described in Strindberg’s texts are subject to changes, shifts and repetitions with variations, such that the archipelago in itself can be read as a mirror of the polyphony of points of view, the variability and the ambiguities we find in his oeuvre at large. Keywords August Strindberg, Stockholm Archipelago, city in literature, nature in literature, mythologies 52 Scandinavica Vol 52 No 2 2013 August Strindberg’s home town of Stockholm, together with its wilder counterpart, the archipelago or skärgård (literally meaning group, or circle, of islands and skerries), plays a large part in Strindberg’s literary universe as well as in his life. The archipelago is ubiquitous in his oeuvre; it occurs in prose as well as in poetry and in drama, and it characterizes both fiction, autobiography and non-fiction (essays, letters and diaries). It can sometimes provide the setting to whole works, but in a series of other works it can be included as one of the settings, or even be mentioned peripherally. -

Miss Julie by August Strindberg

MTC Education Teachers’ Notes 2016 Miss Julie by August Strindberg – PART A – 16 April – 21 May Southbank Theatre, The Sumner Notes prepared by Meg Upton 1 Teachers’ Notes for Miss Julie PART A – CONTEXTS AND CONVERSATIONS Theatre can be defined as a performative art form, culturally situated, ephemeral and temporary in nature, presented to an audience in a particular time, particular cultural context and in a particular location – Anthony Jackson (2007). Because theatre is an ephemeral art form – here in one moment, gone in the next – and contemporary theatre making has become more complex, Part A of the Miss Julie Teachers’ Notes offers teachers and students a rich and detailed introduction to the play in order to prepare for seeing the MTC production – possibly only once. Welcome to our new two-part Teachers’ Notes. In this first part of the resource we offer you ways to think about the world of the play, playwright, structure, theatrical styles, stagecraft, contexts – historical, cultural, social, philosophical, and political, characters, and previous productions. These are prompts only. We encourage you to read the play – the original translation in the first instance and then the new adaptation when it is available on the first day of rehearsal. Just before the production opens in April, Part B of the education resource will be available, providing images, interviews, and detailed analysis questions that relate to the Unit 3 performance analysis task. Why are you studying Miss Julie? The extract below from the Theatre Studies Study Design is a reminder of the Key Knowledge required and the Key Skills you need to demonstrate in your analysis of the play. -

Technologies of the Self: a Seminar with Michel Foucault

Technologies OF THE Self A SEMINAR WITH MICHEL FOUCAULT EDITED BY LUTHER H. MARTIN HUCK GUTMAN PATRICK H. HUTTON TAVISTOCK PU!lLICATIONS LI CONTENTS Introduction Truth, Power, Self: An Interview with Michel Foucault 9 RUX MARTIN Technologies of the Self I 6 MICHEL FOUCAULT Technologies of the Self and Self-knowledge in the Syrian Copyright © 1988 by The University of Massachusetts Press Thomas Tradition 50 All rights reserved LUTHER IL MARTIN Published in 1988 in Great Britain by Tavistock Publications 4 Theaters of Humility and Suspicion: Desert Saints and New Ltd, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4i:i: England Puritans 64 ISBN O 422 62570 1 WILLIAM E. PADEN Printed in the United States of America Hamlet's "Glass of Fashion": Power, Self, and the Reformation LC 87-10756 So KENNETH S. ROTHWELL ISBN 0-87023-592-3 (cloth); 593-1 (paper) 6 Rousseau's Confessions: A Technology of the Self Designed by Barbara Wcrdcn 99 HUCK GUTMAN Set in Linotron Janson at Rainsford Type 7 u , I2 I Printed by Cushing-Malloy and bound by John Dekker & Sons Fouca lt Freud, and the Technologies of the Self PATRICK H. HUTTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 8 The Political Technology of Individuals 145 Technologies of the self. MICHEL FOUCAULT 1. Self (Philosophy) 2. Foucault, Michel Afterword I63 Contributions in concept of the self. I. Foucault, Contributors I 65 Michel. II. Martin, Luther H., 1937- III. l.utman, Huck, 1943- IV. Hutton, Patrick H. Rn450.T39 126 ISBN 0-87023-592-3 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-87023-593-1 (pbk.: alk. -

The Son of a Servant

THE SON OF A SERVANT BY AUGUST STRINDBERG AUTHOR OF "THE INFERNO," "ZONES OF THE SPIRIT," ETC. TRANSLATED BY CLAUD FIELD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HENRY VACHER-BURCH G.P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON The Knickerbocker Press 1913 CONTENTS I. FEAR AND HUNGER II. BREAKING-IN III. AWAY FROM HOME IV. INTERCOURSE WITH THE LOWER CLASSES V. CONTACT WITH THE UPPER CLASSES VI. THE SCHOOL OF THE CROSS VII. FIRST LOVE VIII. THE SPRING THAW IX. WITH STRANGERS X. CHARACTER AND DESTINY AUGUST STRINDBERG AS NOVELIST From the Publication of "The Son of a Servant" to "The Inferno" (1886-1896) A celebrated statesman is said to have described the biography of a cardinal as being like the Judgment Day. In reading August Strindberg's autobiographical writings, as, for example, his Inferno, and the book for which this study is a preface, we must remember that he portrays his own Judgment Day. And as his works have come but lately before the great British public, it may be well to consider what attitude should be adopted towards the amazing candour of his self-revelation. In most provinces of life other than the comprehension of our fellows, the art of understanding is making great progress. We comprehend new phenomena without the old strain upon our capacity for readjusting our point of view. But do we equally well understand our fellow-being whose way of life is not ours? We are patient towards new phases of philosophy, new discoveries in science, new sociological facts, observed in other lands; but in considering an abnormal type of man or woman, hasty judgment or a too contracted outlook is still liable to cloud the judgment. -

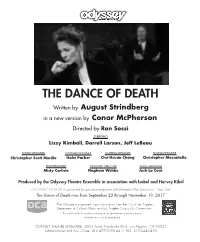

THE DANCE of DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a New Version by Conor Mcpherson Directed by Ron Sossi

THE DANCE OF DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a new version by Conor McPherson Directed by Ron Sossi STARRING Lizzy Kimball, Darrell Larson, Jeff LeBeau SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Christopher Scott Murillo Halei Parker Chu-Hsuan Chang Christopher Moscatiello PROP DESIGNER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR STAGE MANAGER Misty Carlisle Nagham Wehbe Josh La Cour Produced by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in association with Isabel and Harvey Kibel THE DANCE OF DEATH is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service Inc., New York The Dance of Death runs from September 23 through November 19, 2017 The Odyssey is supported in part by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs, and Los Angeles County Arts Commission The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE: 2055 South Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025 Administration and Box Office: 310-477-2055 ext 2 FAX: 310-444-0455 CAST (in order of appearance) THE CAPTAIN .................................................................Darrell Larson ALICE .............................................................................Lizzy Kimball KURT .................................................................................Jeff LeBeau SETTING An Island Fortress near a port in Sweden, Early 20th Century Running time: Two hours There will be one fifteen-minute intermission. This production is dedicated to Sam Shepard. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Dance of Death has amazing significance to the whole world of contemporary drama. The "trapped" nature of its characters feels like Sartre's No Exit (and its classic line "Hell is other people"). And its foreshadow- ing of Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is uncannily prescient, almost as if Albee "channeled" Strindberg in cooking up his own mixture of raucous verbal battle and deadly humor. -

Andreas Jonathan Châtel August Strindberg

EANDR AS A nameless man, a wandering lady, a street corner; the starting point of Andreas, adaptation of the first part of To Damascus by Jonathan Châtel, I EN brings together the conditions necessary for a potential new beginning for the Stranger invented by Strindberg. Exiled in a strange country and cut off from all social ties, he waits, unknowing. Will he disappear? Will he come back to life? His encounter with the Lady awakens in him the hope of finding his way back to childhood, and thus to a potential future, but the past and its spectres threaten to drag him down different paths. Which should he take, if he wants to lose or to find himself again? Translating and adapting August Strindberg’s epic, in which he sees an attempt by the writer to reinvent himself, Jonathan Châtel emphasises the mirror effect between the characters surrounding the Stranger. Seen again and again under different guises, the feeling they instill is reminiscent of those dreams in which different figures share the same face. By playing with the notion of dream, Jonathan Châtel is able to reveal the forgotten name of the Stranger, Andreas, to give form to his confrontation with the Absolute, and to question the struggle of a man against his own demons. The show will premiere on 4 July, 2015 at the Cloître des Célestins, Avignon. JONATHAN CHÂTEL Trained as an actor, with a degree in philosophy and in theatre studies, Jonathan Châtel works as an actor, a playwright, and a director, before leaving for Oslo for three years.