Origin Al Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthoney Udel 0060D

INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2018 © 2018 Cheryl Anthoney All Rights Reserved INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Muqtedar Khan, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, -

A Study on the Depiction of Substance Usage in Contemporary Malayalam Cinema

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-8, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in A Study on the Depiction of Substance Usage in Contemporary Malayalam Cinema. Sachin Krishna1 & Sreehari K G2 1Master of Journalism and Mass Communication 2Assistant Professor 1,2Department of Visual Media, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi Abstract: This paper attempts to determine whether medal. The sixties was a period of an intellectual contemporary Malayalam films have an influence awakening in Malayalam cinema which made its in the increase of substance usage among the presence all over India and the world. Chemeen audience. This is precisely focused due to the fact (1965) directed by Ramu Kariat (Saran, 2012) that recent movies released in the new generation which was based on a novel of the same name by film movement of Malayalam have an increase in Thakazhi Shivashankara Pillai was immensely the onscreen depictions of alcohol and other kinds popular and became the first Malayalam film to of drugs. These movies are shot in such a way that win the National Film Award for Best Feature film. depicts the characters indulging in the use of these This was also the period when Malayalam cinema substances in a glamorized manner as if they are became much more organized and acclaimed promoting its use amongst the audiences. For this, filmmakers such as Adoor Gopalakrishnan and G. selected films released in the previous four years Aravindan began their career. that earned the biggest box office revenues were selected for analysis. This paper also tries to It was in the seventies that Malayalam cinema examine whether these onscreen depictions have entered a new phase of growth that reflected the any significant persuasion among the audiences. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

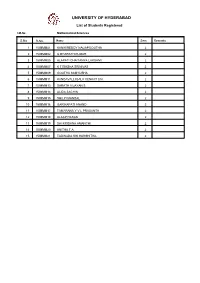

University of Hyderabad

UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 15IMMM01 KANIKIREDDY NAGAPOOJITHA 2 2 15IMMM02 G BHARATH KUMAR 2 3 15IMMM05 ALAPATI CHAITANYA LAKSHMI 2 4 15IMMM07 K TITIKSHA SRINIVAS 2 5 15IMMM09 GOUTHA SAMYUSHA 2 6 15IMMM11 KANDAVALLI BALA VENKAT SAI 2 7 15IMMM13 SARATH VIJAYAN S 2 8 15IMMM14 ALIDA SACHIN 2 9 15IMMM15 SHILPI MANDAL 2 10 15IMMM16 GARIKAPATI ANAND 2 11 15IMMM17 TAMARANA Y V L PRASANTH 2 12 15IMMM18 ALAAP HASAN 2 13 15IMMM19 SAI KRISHNA AMANCHI 2 14 15IMMM20 ANITHA.T.A 2 15 15IMMM21 TADINADA SRI HARSHITHA 2 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 14IMMM01 P R NANDA KUMARI 4 2 14IMMM03 RUDDARRAJU AMRUTHA 4 3 14IMMM04 SAMANAPALLI SRICHANDRA 4 4 14IMMM08 MADISHETTI SAIKIRAN 4 5 14IMMM13 BODA SWAROOPA 4 6 14IMMM14 TAPONITYA SAMANTARAY 4 7 14IMMM16 SAPPIDI SANJAY 4 8 14IMMM17 PINJARI HUSSAIN PEERA 4 9 14IMMM19 KAUSTUB MALLAPRAGADA 4 10 14IMMM20 PUJARI MANISH MADHAV 4 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 12IMMM16 KORUTLA ROHITHKUMAR 6 2 13ICMC20 REBALLI PRIYANKA 6 3 13IMMM01 EESHAN HASAN 6 4 13IMMM05 AKINEPALLY PRATIMA RAO 6 5 13IMMM06 SILADITYA BASU 6 6 13IPMP18 S V SRIHARSHA 6 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 11IMMM17 DEEPAK PAWAR 8 2 12ILMB24 BASAVANAGA AVINASH KUMAR 8 3 12IMMM06 KODIMYALA SHARANYA 8 4 12IMMM07 NAMRATA ARVIND 8 5 12IMMM08 SUBHAS CHANDRA KOLLI 8 6 12IMMM10 AMEYA PHADKE 8 7 12IMMM11 ATTAL SURYA 8 8 12IMMM13 A RAMADEVI 8 9 12IMMM21 KOPPULA BALARAJU 8 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K. -

Coimbatore – 641 029

KONGUNADU ARTS AND SCIENCE COLLEGE (Autonomous) Coimbatore – 641 029 DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY Name : Dr. R. RANJITH KUMAR Designation : Assistant Professor Qualification : M.Sc., Ph.D. Date of Birth : 05/06/1984 Staff ID : U/TS/621 Area of Specialization : Phytonanomedicine Address for Communication : PG and Research Department of Biotechnology Mobile Number : (+91) 9843925312 Email ID : [email protected] Institution Mail ID : [email protected] Teaching Experience : UG - 1 Year PG -1 Year Research Experience : 7 Years 2 months Research Guidance : M.Phil Ph.D Research Completed Ongoing M.Phil Nil Nil Ph.D Nil Nil NET / SET Qualified : Nil Membership in Professional Bodies : Indian Science Congress Association : Nilgiris Education and Research Foundation Other Qualification(s) : - 1 ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE Ph.D., (FT) (2011-2016) Discipline : BIOTECHNOLOGY (Highly Commended) Institution : Dr. N.G. P. Art and Science College, Coimbatore. University : Bharathiar University M.Sc., (2005-2007) Discipline : BIOTECHNOLOGY Institution : SNMV College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore University : Bharathiar University B.Sc., (2002-2005) Discipline : BIOCHEMISTRY Institution : SNMV College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore University : Bharathiar University Area of Interest Plant Biotechnology, Medicinal nanotechnology, Nanotechnology and Toxicology, Chromatography, Nanobiotechnology. Title of the Thesis Ph.D., Phytochemicals, antioxidant and bioinspired silver nanoparticles studies on betel nuts and betel leaf-As antibacterial and anticancer agent. .CURRENT POSITION . JUNE 2018– TILL DATE Position #1 : Assistant Professor in Biotechnology, Kongunadu Arts and Science College, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. Experience : 18 June 2108 to Till Date [Cont....] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE SUMMARY DECEMBER 2017 – MAY 2018 Position #1 : Assistant Professor in Biotechnology, Nehru Arts and Science College, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. -

Parichya Patra.P65

Student Paper PARICHAY PATRA Spectres of the New Wave : The State of the Work of Mourning, and the New Cinema Aesthetic in a Regional Industry 1 Introduction My title refers to Derrida’s controversial account of his concern with Marx amidst the din and bustle of the ‘end of history’. Time was certainly out of joint and the pluralistic outlook of the great thinker was pitted against the monolith that orthodox communists used to uphold. My primary concern in the paper would be an account of the Malayalam film industry in its post-New Wave phase as well as a handful of filmmakers whose works seem to be difficult to categorize. Within the domain of the popular and amidst the mourning from the film society circle for the movement that lasted no longer than a decade, these films evoke the popular memory of the New Wave. Though up in arms against the worthy ancestors, these filmmakers are unable to conceal their indebtedness to the latter. The New Wave too was not without its heterogeneity, and the “disjointed now” that I am talking about is something “whose border would still be determinable”. I would like to consider the possibility of moving towards translocal contexts without shifting our focus from a specific site of inquiry which, in this case, is Malayalam cinema. The paper will concentrate upon the phenomenon known JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 81 as the resurfacing/resurgence of art cinema aesthetics in Indian cinema. Recent scholarly interest in the history of this forgotten film movement is noticeable, more so because it was ignored in the age of disciplinary incarnation of cinematic scholarship in India. -

Marketing of Malayalam Films Through New Media

MARKETING OF MALAYALAM FILMS THROUGH NEW MEDIA ANMI ELIZABETH SABU Registered Number: 1424024 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Communication Studies CHRIST UNIVERSITY Bengaluru 2016 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies ii CHRIST UNIVERSITY Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Anmi Elizabeth Sabu Registered Number: 1424024 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ [CHANDRASEKHAR VALLATH] _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ iii iv I, Anmi Elizabeth Sabu, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: v vi CHRIST UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT Marketing of Malayalam Films through New Media Anmi Elizabeth Sabu The research studies the marketing strategies used by Malayalam films through New Media. In this research new media includes Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Whatsapp and instagram. -

Prl Sub Court Thalassery Cause List 25-01-2021 to 30-01

r7 9tr- 4, f, 1a-ie h.{ 2O2O Da Hon'ble High Court of Kerala. Separate cause list for 25.01.2021 Civil cases Advocates Adr.K.P.Hareendran, os.37/2077 Adv.Sheela.V.l, Adv.O.G.Premarajan o s.19/,2 019 Adv.K.Mukundan, Adv.M.K.Ranjitlr os.101,,2019 Adv.P.Jayanandan, Adv.i(.A.Philip Ad\.V.K.Shyamaprasad, Adv.V.Raju, 4l os.1./2017 Ad1. K.K.Prasad, Adv.Padmaja Surendran Adv.l( M Purushothaman, Adv.P I( Mohan FDIA.755/2010 in 5 Nambiar, Adv.V K Shyamaprasad. Adv.K os.201,/2006 Sathyan, Adv.V P Mahamood. Adv.M"K.Pral<ash, Adv.Sreeesh.l(, FDIA.352/2077 iD Adr'.''r K Shyamaprasad, Adv.K Sathyan, os.335,/2010 Adv.V P Mahamood. EP.1,s/2017 Adr'.Beena l(aliyath. Adr'.U.Geetha Ad\'. V.K.Ranjith, Adv.P.K.Balakrishnan, AS.s7/2O76 Adv.N.V.l Iimaja. Adv.Binni.M Adv. r4arv Mathew, Addl. Govt. Pleader, 45.59 /2076 Adv.K.Ajithkr,lmar. AS.5 B,/2018 Ad\,.'l homas Smith.A.S, Adv.K.Vinod Raj. FDIA.809/2013 in Adv.P K.Balakrishnan, Adv.l'.Sunil os.459/201"1 Kumar IA.7/2020 in Adv.O.G. ?remarajan, FDtA.4476/7999 Adv.K.Sankal a Narayanan Criminal Cases Advocates r sc.511/2014 Addl. i']ublic Prosecutor. Adv.llcthnakumar sc.907/2074 Addl. Ptiblic Prosecutor, Adv.V. P.lian jirh Rumar Copy to L,,{. The Hon ble District Courr, Thalassery. 2. The Secretary, Bar Association, 'l'halassery 3. -

We Tv - Feature Film Schedule for September 2019 Name of the Film Day Time

WE TV - FEATURE FILM SCHEDULE FOR SEPTEMBER 2019 NAME OF THE FILM DAY TIME DATE 01.09.2019 Loham Sunday 09.00AM 01.09.2019 Pathemaari SundayAN 02.30PM 01.09.2019 Oru Vadakkan Selfi SundayNIGHT08.30PM 02.09.2019 Thuruppugulan Monday 09.00AM 02.09.2019 Amma Ammayiamma MondayAN 02.30PM 02.09.2019 Jilla (Dubbed) MondayNIGHT08.30PM 03.09.2019 Vandan vendran (Dubbed) Tuesday 09.00AM 03.09.2019 Singham II (Dubbed) TuesdayAN 02.30PM 03.09.2019 Premam TuesdayNIGHT08.30PM 04.09.2019 Oppam Wednesday 09.00AM 04.09.2019 Kudumbasametham WednesdayAN02.30PM 04.09.2019 Malarvadi Arts Club WednesdayNI0G8H.3T0PM 05.09.2019 Njan Salperu Ramankutty Thursday 09.00AM 05.09.2019 Oppam Oppathinoppam ThursdayAN 02.30PM 05.09.2019 Rajini Murugan (Dubbed) ThursdayNIGH0T8.30PM 06.09.2019 Anjaan (Dubbed) Friday 09.00AM 06.09.2019 Druvangal 16 (Dubbed) FridayAN 02.30PM 06.09.2019 SethuPathi (Dubbed) FridayNIGHT 08.30PM 07.09.2019 Ji (dubbed) Saturday 09.00AM 07.09.2019 Varalaru (Dubbed) SaturdayAN 02.30PM 07.09.2019 Red (Dubbed) SaturdayNIGH0T8.30PM 08.09.2019 Anjaneya (Dubbed) Sunday 09.00AM 08.09.2019 Kakkakuyil SundayAN 02.30PM 08.09.2019 Puli (Dubbed) SundayEVE 05.30PM 08.09.2019 Ustaad SundayNIGHT08.30PM 09.09.2019 Kaashmora (Dubbed) Monday 09.00AM 09.09.2019 Mersal (Dubbed) MondayAN 02.30PM 09.09.2019 Crazy Gopalan MondayEVE 05.30PM 09.09.2019 KO 2 (Dubbed) MondayNIGHT08.30PM 10.09.2019 Thuppakki (Dubbed) Tuesday 09.00AM 10.09.2019 Rajanimurugan TuesdayAN 02.30PM 10.09.2019 Vedhalam (Dubbed) TuesdayEVE 05.30PM 10.09.2019 Kaththi (Dubbed) TuesdayNIGHT08.30PM 11.09.2019 -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) The Mirage of Women Empowerment: Disguised Misogyny in Kanmadam and 22 Female Kotttayam Anjitha S Kurup Guest Lecturer P.G Department of English St Cyrils College Adoor PO Kerala Abstract: Malayalam cinema especially the domain of parallel film has been evidently realistic and true to life in discussing the social injustices, imbalances and multifarious activities. Apart from this entire recognition, Malayalam cinemas both offbeat and commercial rarely produced women characters with significance. There are certain woman characters in Malayalam cinema which are held in esteem for being the epitome of empowered females like Clara, a prostitute with a great sense of dignity in Thoovanathumbikal and Bhadra, a vengeful peasant woman in Kannezhuthi Pottum Thottu. Even though these female characters have managed to maintain cult followers and admirers in Kerala, Malayalam films still remain as the biggest purveyors of misogyny. But things appear to change after the outbreak of the maverick set of film technicians and actors came to be known as the “new generation” movement in Malayalam Cinema. Films like 22 Female Kottayam, Salt and pepper, Amen and 5 Sundarikal are lauded with applause for its undismayed rendition of intrepid, persuasive, and empowered female characters. In this, paper two films from two millennia are taken to analyse the concept of patriarchal supremacy in disguise of women empowerment. The two films in this paper, i.e. Kanmadam written and directed by Lohitadas and 22 Female Kottayam directed by Ashiq Abu have been analysed as making arduous attempts to prove themselves as films centred on women of strength but in reality upheld the ultimate victory of patriarchal consciousness. -

Kairali Tv - Feature Film Schedule for September 2019 Date Name of the Film Day Time

KAIRALI TV - FEATURE FILM SCHEDULE FOR SEPTEMBER 2019 DATE NAME OF THE FILM DAY TIME 01.09.2019 Anjaan (Dubbed) Sunday 08.30AM 01.09.2019 Inspector General 'IG' Sunday 12NOON 01.09.2019 Ustaad SundayEVE 04.00PM 02.09.2019 Kaashmora (Dubbed) Monday 11.30AM 02.09.2019 Villu (Dubbed) Monday 04.00PM 03.09.2019 Ennu Nintte Moideen Tuesday 11.30AM 03.09.2019 Amma Ammayiamma Tuesday 04.00PM 04.09.2019 Thirunaal (Dubbed) Wednesday 12NOON 04.09.2019 Kakkakuyil Wednesday 04.00PM 05.09.2019 Druvangal 16 (Dubbed) Thursday 12NOON 05.09.2019 Thuppakki (Dubbed) Thursday 04.00PM 06.09.2019 Puli (Dubbed) Friday 09.00AM 06.09.2019 Thalaiva (Dubbed) Friday 12NOON 06.09.2019 Kaavalan (Dubbed) FridayEVE 04.00PM 07.09.2019 Mersal (Dubbed) Saturday 08.30AM 07.09.2019 Joseph Saturday 12NOON 07.09.2019 KO 2 (Dubbed) SaturdayEVE 04.00PM 07.09.2019 Junga (Dubbed) SaturdayPRIME 07.00PM 08.09.2019 Vivegam (Dubbed) Sunday 08.00AM 08.09.2019 Maari 2 (Dubbed) Sunday 12NOON 08.09.2019 Saamy 2 (Dubbed) SundayEVE 04.00PM 08.09.2019 Perambu (Dubbed) SundayPRIME 07.00PM 09.09.2019 Kaththi (Dubbed) Monday 08.00AM 09.09.2019 Junga (Dubbed) Monday 11.30AM 09.09.2019 Crazy Gopalan MondayEVE 04.00PM 09.09.2019 AdangaMaru (Dubbed) MondayPRIME 07.00PM 10.09.2019 Kochi Rajavu Tuesday 08.30AM 10.09.2019 PagadiAattam (Dubbed) Tuesday 12.30PM 10.09.2019 Kabali (Dubbed) TuesdayEVE 04.00PM 10.09.2019 7 Seven (Dubbed) TuesdayPRIME 07.00PM 11.09.2019 7 Seven (Dubbed) Wednesday 09.00AM 11.09.2019 Unda Wednesday 12.30PM 11.09.2019 Ratsasan (Dubbed) WednesdayEVE 03.30PM 11.09.2019 Viswasam