Discovering the Twelve Steps Through the Creative Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 6 6-1-2001 (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Robert Neustadt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the American Literature Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Neustadt, Robert (2001) "(Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Abstract Masks serve as particularly effective props in contemporary Mexican and Chicano performance art because of a number of deeply rooted traditions in Mexican culture. This essay explores the mask as code of honor in Mexican culture, and foregrounds the manner in which a number of contemporary Mexican and Chicano artists and performers strategically employ wrestling masks to (ef)face the mask- like image of Mexican or U.S. nationalism. I apply the label "performance artist" broadly, to include musicians and political figures that integrate an exaggerated sense of theatricality into their performances. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Dread Standard, PDF Version Layout Done with Adobe® Indesign® CS 3 on Mac OS X, Using the Typefaces Attic and Book Antiqua

Dread TID002 Table of Contents Chapter 1: To Begin With . 3 Chapter 2: Briefly, the Rules . 6 . Chapter 3: A Question of Character . 16 Chapter 4: How to Host a Dread Game . .28 . Chapter 5: How to Create a Dread Game . 38 . Chapter 6: The Suspenseful Game . 50 Chapter 7: The Supernatural Game . 53 . Chapter 8: The Mad Game . 56 . Chapter 9: The Moral Game . 59 Chapter 10: The Mysterious Game . 62 Chapter 11: The Gory Game . 65. Appendix: Alternate Methods . 68 Story: Beneath the Full Moon . 70 Story: Beneath a Metal Sky . 82 Story: Beneath the Mask . 89 . Dread is a horror game . There is no reason that the content of any game of Dread need be any more horrifying than you wish it to be, and therefore Dread can be suitable for nearly any age . However, the contents of this book delve into mature topics at points, in order to facilitate groups who enjoy those sorts of horror, so please exercise discretion when passing this book around . In par- ticular, Chapter 11 is not suitable for our younger players . For Leslie Scott . original concept by Epidiah Ravachol and woodelf development by The Impossible Dream writing by Epidiah Ravachol editing and additional writing by The Impossible Dream copy editing by Jere Foley layout and cover design by woodelf back cover illustration by Christy Schaefer illustrations on pages 13, 20, 35, 38, 49, 51, 57 by Taylor Winder illustrations on pages 7, 15, 28, 31, 45, 53, 60, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 69 by Jill Krynicki Dread Standard, PDF version Layout done with Adobe® InDesign® CS 3 on Mac OS X, using the typefaces Attic and Book Antiqua. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

Sin City Hc01. Een Wreed Vaarwel Gratis Epub, Ebook

SIN CITY HC01. EEN WREED VAARWEL GRATIS Auteur: Frank Miller Aantal pagina's: 208 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9788868738990 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Sin City NL HC 01 Een wreed vaarwel Het album is een éénmalige uitgave en is verrijkt met een 16 paginatellend dossier met schetsen, scenario's, foto's en andere achtergond informatie over het totstand komen van dit verhaal. Deel 9 in de reeks Biebel De Stroken. De kaalhoofdige stripkleuter Biebel beleeft met zijn vriendje Reggie de meest absurde avonturen. In deze mooi uitgevoerde strokenreeks verschijnen de gags voor het eerst in kleur én eindelijk helemaal compleet. Foltering zal hun deel worden in zijn verrotte gevangenis. Het vierde deel van het magistrale meesterwerk, gebaseerd op de roman van de bekende Duitse fantasy-auteur Wolfgang Hohlbein. Op een ochtend in Galileo ziet een oude Joodse visser vol verbijstering hoe zijn zoons alles in het werk stellen om een zekere Jezus van Nazareth te volgen. Hij besluit om alles te doen om zijn kroost te vinden en ze terug te brengen. Al snel vergezellen andere vaders hem op deze tocht. Een prachtig album dat leest als een roadmovie. WAW Dat is natuurlijk normaal voor een stuntvrouw. Een klein vissersdorpje in het uiterste zuiden van Italië is het toneel van een nieuw avontuur: een jonge vrouw wordt verdronken teruggevonden, een Engelse heer is stomdronken op alle uren van de dag, er zijn vier schijnbaar zachtmoedige karakters en onuitstaanbare tweelingen. Mauro Caldi gaat, in een prachtige Jaguar XK, op onderzoek uit op Daarnaast een kort verhaal over het leven van Sigmar Rhone, één van de machtigste leden van de Trust. -

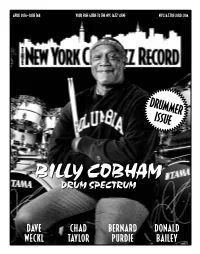

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Shedding the Mask: Using the Literature of the Civil Rights Era to Reveal the Motivations of the Movement

Shedding the Mask: Using the Literature of the Civil Rights Era to Reveal the Motivations of the Movement Emily Williams Introduction This is a unit for students in my Advanced Placement United States Government and Politics class that examines the transition of thought that occurred in the African American community from the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement through the 1970s. The students in AP Government are seniors who have already completed studies on the civil rights movement in the AP class as well as their US History and Civics and Economics classes. The Civil Rights Era in America is a topic that students enjoy studying. They are drawn to the themes of alienation and oppression. I believe students relate strongly to these themes because, as teenagers, they see their lives as lacking in certain freedoms: adults control how they spend much of their time, they are often not able to make decisions for themselves, and they must often hide who they are to please the people around them. It is this last point that will be the center of my unit. I want students to understand more than the important people, events, and dates of the Civil Rights Movement that are studied in the Advanced Placement Government curriculum. I want them to understand the motivations of the people involved in the movement, and reading the literature of the era will provide that opportunity. African-American culture is rich with literature and music that chronicles what it is like to be marginalized in society. Unfortunately, students explore very little of this literature in school. -

Чик Кñšñ€Ð¸ÑÐлбуð¼

Чик ÐšÑŠÑ€Ð¸Ñ ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Circulus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/circulus-5121711/songs Circling In https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/circling-in-5121542/songs The Complete "Is" Sessions https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-complete-%22is%22-sessions-7727091/songs Touchstone https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/touchstone-7828728/songs The Vigil https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-vigil-17030425/songs Children's Songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/children%27s-songs-5098223/songs Inner Space https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/inner-space-6035581/songs Expressions https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/expressions-5421714/songs Rendezvous in New York https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/rendezvous-in-new-york-7312835/songs Delphi II & III https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/delphi-ii-%26-iii-5254403/songs Trio Music https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/trio-music-7843087/songs Alive https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/alive-4727412/songs Three Quartets https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/three-quartets-7797708/songs Forever https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/forever-28452035/songs Time Warp https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/time-warp-17034175/songs The Chick Corea Elektric Band https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-chick-corea-elektric-band-3986254/songs Tap Step https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/tap-step-7684375/songs Beneath the -

Lester Young and the Birth of Cool (1998) Joel Dinerstein

Lester Young and the Birth of Cool (1998) joel dinerstein ....... American studies scholar Joel Dinerstein designed and teaches a course at the University of Texas at Austin on the history of being cool in America. In this essay from The Cool Mask (forthcoming) he shows how the African American concept of cool synthesizes African and Anglo-European ideas, describing African American cool as both an expressive style and a kind of public composure. For African Americans, cool resolves the conflict between com- peting needs to mask and to express the self, a paradox exacerbated by historical exigencies of life in the United States. For Dinerstein, the jazz musician Lester Young modeled a strategy of self-presentation that became the dominant emotional style of African Ameri- can jazz musicians and several generations of African American men. Miles Davis’s 1957 collection The Birth of the Cool tends to serve as a lightning rod for discussions of ‘‘cool’’ in jazz and African American culture.∞ A spate of jazz recordings, however, testify to the importance of being ‘‘cool’’—of main- taining emotional self-control—during World War II as a strategy for dealing with dashed hopes of social equality. The messages of Erskine Hawkins’s hit, ‘‘Keep Cool, Fool’’ (1941) and Count Basie’s ‘‘Stay Cool’’ (1946) and the cerebral quality of Charlie Parker’s ‘‘Cool Blues’’ (1946) testify to a new valuation of public composure and disparagement of the outward emotional display long associated with stereotypes of blacks, from Uncle Tom to the happy-go-lucky ‘‘southern -

Honor Ensemble Important Event Procedures

Honor Ensemble Important Event Procedures National Presenting Sponsor March 9-12 2016 ⋅ Indianapolis, IN Congratulations and welcome to the 25th Annual Music for All National Festival, presented by Yamaha. The following are details associated with your participation in the week's activities. Please be familiar with this information, bring a copy with you to the Festival and pass along the critical items to your parents. It is a good idea for your parents to keep a copy at home, as well, if they are not attending the Festival. FESTIVAL CONTACT INFORMATION Please keep the following contact information should you have questions during the Festival. FESTIVAL HOTELS: Marriott Place Indianapolis JW Marriott Indianapolis SpringHill Suites Fairfield Inn & Suites Festival Headquarters 601 W. Washington Street 501 W. Washington Street Honor Ensemble Hotel Indianapolis, IN 46204 Indianapolis, IN 46204 10 S. West Street 317.972.7293 317.636.7678 Indianapolis, IN 46204 317.860.5800 FESTIVAL PERFORMANCE VENUES National Concert Band Festival Performances Orchestra America National Festival Performances Honor Band and Jazz Band of America Concert Venue Clowes Memorial Hall 4602 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, IN 46208 317.940.9697 (General #) Middle School National Music Festival Performances, National Festival Invited Ensemble Performances Howard L. Schrott Center for the Arts 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, IN 46208 317.940.2787 (General #) Sandy Feldstein National Percussion Festival Performances The Warren Performing Arts Center 9500 East 16th Street Indianapolis, IN 46229 317.532.6280 (General #) Chamber Music Festival Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio St. Indianapolis, IN 46202 317.232.1882 (General #) Honor Orchestra of America Concert Venue Hilbert Circle Theatre Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra 32 East Washington Street, Suite 600 Indianapolis, IN 46204-2919 317.262.1100 (General #) Note: During the Festival, Music for All will operate an on-site headquarters located at the JW Marriott. -

Forgotten Diary

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 Forgotten Diary Heather J. Richardson University of New Orleans, New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Richardson, Heather J., "Forgotten Diary" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2769. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2769 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forgotten Diary A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Poetry by Heather Jennings Richardson B.A. Mary Washington College, 2001 May, 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to show my warm thanks to Professor John Gery for his time, feedback, and encouragement. Also, I would like to show gratitude to Professor Kay Murphy and Gina Ferrara for their time and effort in serving on my committee. -

Females and Feminism Reclaim the Mainstream: New Superheroines in Marvel Comics

FEMALES AND FEMINISM RECLAIM THE MAINSTREAM: NEW SUPERHEROINES IN MARVEL COMICS By Sara Marie Kern A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Middle Tennessee State University December 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Martha Hixon, Chair Dr. David Lavery I dedicate this research to real-life superheroines like my great-grandmother, who risked her reputation to educate women about their bodies. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe an immense debt to my family for supporting me in the pursuit of this degree, which at times seemed unachievable. Their unwavering emotional support and willingness to sacrifice for my benefit was at times overwhelming, and their generosity truly made this dream possible. I am likewise indebted to Dr. Martha Hixon and Dr. David Lavery, who encouraged me to push forward after a year-long furlough; Dr. Hixon’s consistent enthusiasm for my topic—and then my second topic—sustained me when the work was daunting. Finally I would like to thank the other contributors without whom this research would not exist: the creative teams for Thor, Ms. Marvel¸ and Storm; the librarians at the James E. Walker, UC Berkeley, and Berkeley Public libraries; and David Pemberton, who brought me back to Marvel, and helped to keep me sane. Note: the images reproduced in this thesis appear under the Fair Use agreement, and all copyrights remain with DC, Marvel Comics, and Avatar Press. I owe special thanks to these publications for their cooperation. iii ABSTRACT Representations of females in visual media continue to be problematic. As media studies increasingly reveals the influence of visual representation upon our internalized ideologies, the significance of positive female representation only increases.