„George Enescu” Iaşi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania Nicolae GHEORGHIță National University of Music, Bucharest Str. Ştirbei Vodă nr. 33, Sector 1, Ro-010102, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2015; accepted: September 2015) Abstract: In an atheist society, such as the communist one, all forms of the sacred were anathematized and fiercly sanctioned. Nevertheless, despite these ideological barriers, important articles and volumes of Byzantine – and sometimes Gregorian – musicological research were published in totalitarian Romania. Numerous Romanian scholars participated at international congresses and symposia, thus benefiting of scholarships and research stages not only in the socialist states, but also in places regarded as ‘affected by viruses,’ such as the USA or the libraries on Mount Athos (Greece). This article discusses the mechanisms through which the research on religious music in Romania managed to avoid ideological censorship, the forms of camouflage and dissimulation of musicological information with religious subject that managed to integrate and even impose over the aesthetic visions of the Party. The article also refers to cultural politics enthusiastically supporting research and valuing the heritage of ancient music as a fundamental source for composers and their creations dedicated to the masses. Keywords: Byzantine musicology, Romania, 1944–1990, socialist realism, totalitari- anism, nationalism Introduction In August 1948, only eight months after the forced abdication of King Michael I of Romania and the proclamation of the people’s republic (30 December 1947), the Academy of Religious Music – as part of the Bucharest Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, today the National University of Music – was abolished through Studia Musicologica 56/4, 2015, pp. -

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed Va lentina SANDU-DEDIU National University of Music Bucharest Strada Știrbei Vodă 33, București, Ro-010102 Romania New Europe College Bucharest Strada Plantelor 21, București, Ro-023971 Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: November 2017; accepted: January 2018) Abstract: This essay tackles some aspects related to the attitude of the Romanian officials after George Enescu left his country definitively (in 1946). For example, re- cent research through the archives of the former secret police shows that Enescu was under the close supervision of Securitate during his last years in Paris. Enescu did not generate a compositional school during his lifetime, like for instance Arnold Schoen- berg did. His contemporaries admired him, but each followed their own path and had to adapt differently to an inter-war, then to a post-war, Communist Romania. I will therefore sketch the approach of younger composers in relation to Enescu (after 1955): some of them attempted to complete unfinished manuscripts; others were in fluenced by ideas of Enescu’s music. The posthumous reception of Enescu means also an in- tense debate in the Romanian milieu about his “national” and “universal” output. Keywords: Securitate, socialist realism in Romania, “national” and “universal,” het- erophony, performance practice It is a well-known fact that George Enescu did not create a school of composition during his lifetime, neither in the sense of direct professor–student transmission of information, as was the case in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg, nor in the wider sense of a community of ideas or aesthetic principles. His contemporaries admired him, but they each had their own, well-established stylistic paths; in the Stalinist post-war period, some of them subordinated their work to the ideological requirements of socialist realism and it was generally discouraged to discern the subtle, but substantial renewals of Enescu’s musical language. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Constante Şi Deschideri În Cvartetele De Coarde Ale Lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I)

MUZICA nr.1/2010 CREAŢII Monica CENGHER Constante şi deschideri în cvartetele de coarde ale lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I) Interesul lui W.G.Berger pentru genurile instrumentale verificate de proba îndelungată a istoriei, primordiale fiind cvartetul de coarde şi simfonia alături de concertul instrumental şi sonată, s-a concretizat într-o vastă operă de autor, elaborată în spiritul unui virtual dar ingenios dialog cu valorile supreme ale culturii. Sintagma goetheană “dacă vrei să păşeşti în infinit, parcurge finitul din toate direcţiile” este emblematică demersului său artistic. Vocaţia renascentistă de a iscodi concreteţea artei muzicale din mai multe ipostaze (istorice, estetice, matematice, componistice şi nu în ultimul rând interpretative), a fost dublată de însuşirile unei personalităţi profunde, înzestrată cu o fină inteligenţă, generozitate şi fire contemplativă cu nuanţe de blândeţe. “Fenomenul W. Berger – căci a fost un fenomen cu totul neobişnuit – nu s-a produs în locuri obscure sau ascunse, ci în plină lumină”1- releva pe un ton admirativ Pascal Bentoiu. Această forţă iradiantă însoţită de bucuria revelaţiei pe care i-a oferit-o cunoaşterea, l-au călăuzit întreaga viaţă, conturându-i opera de autor pe dimensiuni monumentale, masive şi de o anvergură nemaiîntâlnită la noi. Abundenţa cu care dădea la iveală creaţiile muzicale şi lucrările muzicologice reprezintă amplitudinea aspiraţiilor sale de largă cuprindere, în care erudiţia naşte imaginaţie şi detaliul se generalizează în concepte abstracte. Există o cadenţă în evoluţia lui W.G.Berger. Pe de o parte urmăreşte împlinirea unor ţeluri pe planul gândirii despre muzică, pornind de la analiza resorturilor intime ale fenomenului muzical, conturând liniile de forţă ale curentelor şi mentalităţilor artistice; pe de altă parte, se defineşte printr-o consistentă gândire componistică cu deschideri atât către tradiţii cât şi spre înnoiri. -

Muzeul National X, 1998

GENERALUL LEONARD MOCIULSCHI ÎN CELE TREI RĂZBOAIE DIN PRIMA JUMĂTATE A VEACULUI NOSTRU Vasile Novac Mociulschi Leonard, fiul lui Gheorghe (+) şi al Elenei, de religie ortodoxă, s-a născut la 27 martie 1889. în comuna Siminica, plasa Burdujeni. judeţul Botoşani: căsătorit cu Ecaterina Mintiei, de religie ortodoxă, la 12 iulie 1921. în comuna Sudarea, judeţul Soroca. Studii şi Şcoli: 6 clase secundare; Şcoala Pregătitoare a Ofiţerilor Activi de Infanterie. Şcoala de Tragere a Infanteriei, pe care n-a promovat-o: Cursul de Ski şi Alpinism - Zărneşti. Fapte Meritorii şi Decoraţii: 1. Medalia "Avântul Ţării" 1913: 2. Ordinul "Coroana României" cu spade şi panglică de "Virtutea Militară" în grad de cavaler, pentru bravura şi destoinicia ce a arătat în luptele din 1916-1917: 3. Ordinul "Crucea de Război Franceză" 1917; 4. Ordinul "Steaua României" cu spade şi panglică de "Virtutea Militară" în grad de cavaler pentru bravura şi energia cu care a comandat compania la atacul gării Ocniţa şi satele Noslavcea şi Sincăuţi, recucerind obiectivele ordonate şi capturând două mitraliere în luna ianuarie 1919: 5. Medalia "Crucea Comemorativă" cu băietele: Ardeal, Carpaţi. Oituz. Mărăşli. Tg.Ocna: 6. Seninul onorific pentru 25 de ani de serviciu militar - 1930; 7 Medalia Peleş "Semicentenarul Castelului Peleş" - 1933: 8. Ordinul "Coroana României" în grad de ofiţer - 1923: 9. Ordinul "Coroana României" în grad de comandor cu spade şi panglică de "Virtutea Militară": 10. Ordinul "Steaua României" în grad de comandor şi panglică de "Virtutea Militară"; 11. "Crucea de Fier" clasa Il-a - 24 septembrie 1941; 12. "Crucea de Fier" clasa I-a 15 decembrie 1941; 13. -

Romanian Neo-Protestants in the Interwar Struggle for Religious and National Identity

Pieties of the Nation: Romanian neo-protestants in the interwar struggle for religious and national identity by Iemima Daniela Ploscariu Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Constantin Iordachi Second Reader: Vlad Naumescu CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection i Abstract Neo-protestants (Seventh-Day Adventists, Baptists, Brethren, and Pentecostals) were the fastest growing among the religious minorities in interwar Romania. The American, Hungarian, German, and other European influences on these groups and their increasing success led government officials and the Romanian Orthodox Church to look on them with suspicion and to challenge them with accusations of being socially deviant sects or foreign pawns. Neo- protestants presented themselves as loyal Romanians while still maintaining close relationships with ethnic minorities of the same faith within the country and abroad. The debates on the identity of these groups and the “competition for souls” that occurred in society demonstrate neo- protestants' vision of Romanian national identity challenging the accepted interwar arguments for what it meant to be Romanian. -

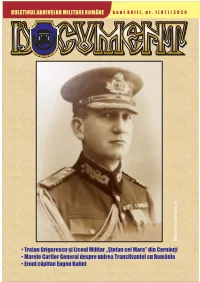

Tipo Document 1 2020.Indd

BULETINUL ARHIVELOR MILITARE ROMÂNE AnulXXIII , nr. 1 ( 87 ) /2020 http://amnr.defense.ro • Traian GrigorescuşŞ i Liceul Militar „ tefan cel Mare” din Cernăuţi • Marele Cartier General despre unirea Transilvaniei cu România • Eroul căpitan Eugen Balint ARHIVELE MILITARE NAŢIONALE ROMÂNE SUMAR Buletinul Arhivelor Militare Româ ne Anul XXIII, nr. 1 (87)/2020 Director fondator STUDII/DOCUMENTE Prof. univ. Dr. Valeriu Florin DOBRINESCU (1943-2003) Publica]ie recunoscut` de c`tre Consiliul Na]ional al Cercet`rii {tiin]ifice din |nv`]`m@ntul Superior [i inclus` \n categoria „D”, cod 241 MihailS adoveanu povesteş te despre ră zboiul nostru Dr. Luminiţ1 a GIURGIU Coperta I: Generalul Traian Grigorescu, aici în grad de colonel Reabilitare cu o condiţie: să fie citaţi peOZ rdin de i pentru fapte de vitejie Coperta IV: 1917. Soldaţ i Colonel Dr. Gabriel-George PĂTRAŞCU 11 români în tranş ee Secţia IMCG nformaţii din arele artier eneral propune un memoriu privind „Î ndreptăţirea Editor coordonator: şi neces i tatea un i r ii T rans i lvan i e i cu R omân i a" Colonel Liviu CORCIU (D ecembrie 1918) Redactor-ş ef: Lector universitar asociat Dr. Alin SPÂNU 16 Dr.Teodora GIURGIU Tel./fax :67 021-318.53.85, 021-318.53.67/03 [email protected] O poveste adevărată Secretar de redacţ: ie Ferdinand I - primul rege al tuturor românilor Dr. Veronica BONDAR (Operaţiile militare ale anului 1919) Redactori: Neculai MOGHIOR 20 Mihaela CĂLIN, Lucian DR Ă GHICI, Dr. OanaAnca OTU, colonelD r. Gabriel -George PĂ TRAŞ CU , Raluca TUDOR Locotenent-colonelulTG raian rigorescu – Coperte: Valentin MACARIE, Nicolae CIOBANU primul comandant alLMŞ iceului ilitar „ tefan cel M are" Tă:ehnoredactare computerizat dinC ernăuţi Măă d lina DANCIU General de brigadă (r) prof. -

Analele Universităłii Din Oradea

MINISTERUL EDUCA łIEI, CERCET ĂRII, TINERETULUI ŞI SPORTULUI ANALELE UNIVERSIT Ăł II DIN ORADEA ISTORIE - ARHEOLOGIE TOM XX 2010 ANALELE UNIVERSIT Ăł II DIN ORADEA FASCICULA: ISTORIE-ARHEOLOGIE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE: EDITORIAL STAFF: Acad. Ioan Aurel-POP (Cluj-Napoca) Editor-in-Chief: Barbu ŞTEF ĂNESCU Nicolae BOC ŞAN (Cluj-Napoca) Associate Editor : Antonio FAUR Ioan BOLOVAN (Cluj-Napoca) Executive Editor: Radu ROMÎNA ŞU Al. Florin PLATON (Ia şi) Members : Rudolf GÜNDISCH (Oldenburg) Sever DUMITRA ŞCU Toader NICOAR Ă (Cluj-Napoca) Roman HOLEC (Bratislava) Viorel FAUR Nicolae PETRENCU (Chi şin ău) Mihai DRECIN GYULAI Eva (Miskolc) Ioan HORGA Frank ROZMAN (Maribor) Ion ZAINEA Gheorghe BUZATU (Ia şi) Gabriel MOISA Ioan SCURTU (Bucure şti) Florin SFRENGEU Vasile DOBRESCU (Târgu Mure ş) Mihaela GOMAN BODO Edith Laura ARDELEAN Manuscrisele, c ărŃile, revistele pentru schimb, precum şi orice coresponden Ńă , se vor trimite pe adresa Colectivului de redac Ńie al Analelor Universit ăŃ ii din Oradea, Fascicula Istorie- Arheologie. The exchange manuscripts, books and reviews as well as any correspondence will be sent on the address of the Editing Staff. Les mansucsrits, les livres et les revues proposé pour échange, ainsi que toute corespondance, seront addreses adresses à la redaction. The responsibility for the content of the articles belongs to the author(s). The articles are published with the notification of the scientific reviewer. Redaction: Dr.ing. Elena ZIERLER (Oradea) Address of the editorial office: UNIVERSITY OF ORADEA Department of -

![Nr. 4 [41]/2011](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1577/nr-4-41-2011-1801577.webp)

Nr. 4 [41]/2011

UNIVERSITATEA NAŢIONALĂ DE APĂRARE „CAROL I” CENTRUL DE STUDII STRATEGICE DE APĂRARE ŞI SECURITATE Nr. 4 [41]/2011 Şos. Panduri, nr. 68-72, sector 5 Telefon: (021) 319.56.49; Fax: (021) 319.55.93 E-mail: [email protected]; Adrese web: http://impactstrategic.unap.ro, http://cssas.unap.ro EDITURA UNIVERSITĂŢII NAŢIONALE DE APĂRARE „CAROL I” IMPACT STRATEGICBUCUREŞTI Nr. 4/2011 1 Revista ştiinţifică trimestrială a Centrului de Studii Strategice de Apărare şi Securitate, clasificată de către Consiliul Naţional al Cercetării Ştiinţifice din Învăţământul Superior la categoria B+ Consiliul editorial: Prof.univ.dr. Teodor Frunzeti, preşedinte Prof. univ. dr. Marius Hanganu Conf.univ.dr. Gheorghe Calopăreanu C.S. I dr. Constantin Moştoflei Prof. dr. Hervé Coutau-Bégarie (Institutul de Strategie Comparată, Paris, Franţa) Prof. dr. John L. Clarke (Centrul European pentru Studii de Securitate „George C. Marshall”) Prof. univ. dr. ing. Adrian Gheorghe (Universitatea Old Dominion, Norfolk, Virginia, SUA) Dr. Frank Libor������������������������������������������������������������������ (Institutul de Studii Strategice, Universitatea de Apărare, Brno, Cehia) Dr. Dario Matika (Institutul de Cercetare şi Dezvoltare a Sistemelor de Apărare, Zagreb, Croaţia) Prof. univ. dr. Ilias Iliopoulos (Colegiul de Război al Forţelor Navale, Atena, Grecia) Ing. dr. Pavel Necas (Academia Forţelor Armate, Liptovsky Mikulas, Slovacia) Dr. Dana Perkins, 7th Civil Support Command - USAREUR, Germania Acad. prof. univ. dr. Alexandru Bogdan, Centrul de Biodiversitate, Academia Română Referenţi ştiinţifici: C.S. I dr. Grigore Alexandrescu C.S. II dr. Alexandra Sarcinschi C.S. III dr. Cristian Băhnăreanu Dr. Richard Stojar Conf.univ.dr. Dorel Buşe Prof.univ.dr. Costică Ţenu Conf.univ.dr. Gheorghe Deaconu Prof. univ. dr. -

AM-2015-12.Pdf

Serie nouã ACTUALITATEA decembrie12 2015 (CLXXIII) 48 pagini MUZICAL~ ISSN MUZICAL~ 1220-742X REVISTĂ LUNARĂ A UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA D i n s u m a r: Uniunea Compozitorilor şi Muzicologilor la 95 de ani Festivalul Internaţional MERIDIAN Festivalul INTRADA, Timişoara Danube Jazz & Blues Festival Rock îndoliat În imagine: Constantin Brăiloiu, Alfred Alessandrescu, Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu George Enescu, Ion Nonna Otescu, Mihail Jora Recunoaştere Preşedintele României Klaus Johannis a înmânat, în cadrul ceremoniei din data de 05.11.2015, UNIUNII COMPOZITORILOR ŞI MUZICOLOGILOR DIN ROMÂNIA (UCMR), cu prilejul aniversării a 95 de ani de la înfiinţarea Societăţii Compozitorilor Români (precursoarea UCMR) şi a aniversării a 20 de ani de la constituirea Alianţei Naţionale a Uniunilor de Creaţie (ANUC), Ordinul „MERITUL CULTURAL” în grad de „OFIŢER”. În argumentarea aferentă distincţiei se menţionează că aceasta se conferă în semn de înaltă apreciere pentru implicarea directă şi constantă în organizarea şi promovarea manifestărilor muzicale, pentru meritele deosebite avute la susţinerea patrimoniului clasic autohton, a creaţiei muzicale contemporane, contribuind astfel la afirmarea internaţională a compozitorilor şi muzicologilor români. DIN SUMAR UCMR la 95 de ani................................1-10 Interviu cu dl. Ulpiu Vlad....................11-12 Festivalul internaţional MERIDIAN.....13-27 Conferinţa OPERA EUROPA.................27-28 Tatiana Lisnic la ONB..........................28-29 Concerte sub... lupă.................................31 Corespondenţă de la Oldenburg...........32-33 Festivalul INTRADA.............................34-35 “In Memoriam #colectiv”....................36-37 “Danube Jazz & Blues Festival”...........38-39 Rock îndoliat......................................42-43 Lansare carte Maria Dragomiroiu........44-45 Discuri................................................46-47 Muzica pe micul ecran.............................48 ACTUALITATEA MUZICALĂ Nr. 12 Decembrie 2015 1 UCMR 95 timp de răzBOI. -

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin 1 Aubade (1899) 3:46 17 Nocturne ‘Villa d’Avrayen’ (1931–36)* 6:11 Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne (1900; arr. Lupu)** 13:38 18 Hora Unirei (1917) 1:40 2 Pastorale 3:30 3 Menuet triste 4:29 Aria and Scherzino 4 Nocturne 5:39 (c. 1898–1908; arr. Lupu)** 5:12 19 Aria 2:17 5 Sarabande (c. 1915–20)* 4:43 20 Scherzino 2:55 6 Sérénade lointaine (1903) 4:49 TT 79:40 7 Andantino malinconico (1951) 2:15 Sherban Lupu, violin – , Prelude and Gavotte (1898)* 10:21 [ 20 conductor –, – 8 Prelude 4:32 Masumi Per Rostad, viola 9 Gavotte 5:49 Marin Cazacu, cello , Airs dans le genre roumain (1926)* 7:12 Dmitry Kouzov, cello , , 10 I. Moderato (molto rubato) 2:06 Ian Hobson, piano , , , , , 11 II. Allegro giusto 1:34 Ilinca Dumitrescu, piano , 12 III. Andante 2:00 Samir Golescu, piano , 13 IV. Andante giocoso 1:32 Enescu Ensemble of the University of Illinois –, – 20 14 Légende (1891) 4:21 , , , , , , DDD 15 Sérénade en sourdine (c. 1915–20) 4:21 –, –, –, , – 20 ADD 16 Fantaisie concertante *FIRST RECORDING (1932; arr. Lupu)* 11:04 **FIRST RECORDING IN THIS VERSION 16 TOCC 0047 Enescu Vol 1.indd 1 14/06/2012 16:36 THE UNKNOWN ENESCU VOLUME ONE: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN by Malcolm MacDonald Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne, Sarabande, Sérénade lointaine, Andantino malinconico, Airs dans le genre roumain, Fantaisie concertante and Aria and Scherzino recorded in the ‘Mihail Jora’ Pablo Casals called George Enescu ‘the greatest musical phenomenon since Mozart’.1 As Concert Hall, Radio Broadcasting House, Romanian Radio, Bucharest, 5–7 June 2005 a composer, he was best known for a few early, colourfully ‘nationalist’ scores such as the Recording engineer: Viorel Ioachimescu Romanian Rhapsodies. -

Studia Musica – 1 – 2017

MUSICA 1/2017 STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS BABEŞ-BOLYAI MUSICA 1/2017 JUNE REFEREES: Acad. Dr. István ALMÁSI, Folk Music Scientific Researcher, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary Univ. Prof. Dr. István ANGI, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Gabriel BANCIU, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Habil. Stela DRĂGULIN, Transylvania University of Braşov, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Habil. Noémi MACZELKA DLA, Pianist, Head of the Arts Institute and the Department of Music Education, University of Szeged, "Juhász Gyula" Faculty of Education, Hungary College Prof. Dr. Péter ORDASI, University of Debrecen, Faculty of Music, Hungary Univ. Prof. Dr. Pavel PUŞCAŞ, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Valentina SANDU-DEDIU, National University of Music, Bucharest, Romania Univ. Prof. Dr. Ilona SZENIK, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Acad. Univ. Prof. Dr. Eduard TERÉNYI, „Gh. Dima” Music Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary Acad. College Associate Prof. Dr. Péter TÓTH, DLA, University of Szeged, Dean of the Faculty of Musical Arts, Hungary, Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts – Budapest, Hungary EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Associate Prof. Dr. Gabriela COCA, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania PERMANENT EDITORIAL BOARD: Associate Prof. Dr. Éva PÉTER, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Lecturer Prof. Dr. Miklós FEKETE, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Assist. Prof. Dr. Adél FEKETE, Babeş-Bolyai University, Reformed Theology and Musical Pedagogy Department, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Assist.