ARTES Vol. 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

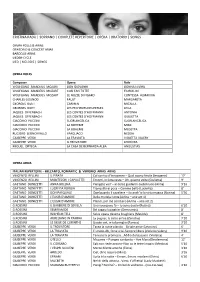

Soprano | Complete Repertoire | Opera | Oratorio | Songs

CRISTINA RADU | SOPRANO | COMPLETE REPERTOIRE | OPERA | ORATORIO | SONGS OPERA ROLES & ARIAS ORATORIO & CONCERT ARIAS BAROQUE ARIAS LIEDER-CYCLE LIED | MELODIE | SONGS OPERA ROLES Composer Opera Role WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART DON GIOVANNI DONNA ELVIRA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART COSI FAN TUTTE FIORDILIGI WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART LE NOZZE DI FIGARO CONTESSA ALMAVIVA CHARLES GOUNOD FAUST MARGARETA GEORGES BIZET CARMEN MICAELA GEORGES BIZET LES PECHEURS DES PERLES LEILA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN ANTONIA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN GIULIETTA GIACOMO PUCCINI SUOR ANGELICA SUOR ANGELICA GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MIMI GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MUSETTA RUGIERO LEONCAVALLO I PAGLIACCI NEDDA GIUSEPPE VERDI LA TRAVIATA VIOLETTA VALERY GIUSEPPE VERDI IL TROVATORE LEONORA MIGUEL ORTEGA LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA ANGUSTIAS OPERA ARIAS ITALIAN REPERTOIRE – BELCANTO, ROMANTIC & VERISMO ARIAS ARIAS VINCENZO BELLINI IL PIRATA Col sorriso d’innocenza – Qual suono ferale (Imogene) 12’ VINCENZO BELLINI MONTECCHI I CAPULETTI Eccomi, in lieta vesta – Oh, quante volte (Giulietta) 9’ GAETANO DONIZETTI ANNA BOLENA Piangete voi? – al dolce guidarmi castel natio (Anna) 9’16 GAETANO DONIZETTI LUCREZIA BORGIA Tranquillo ei posa – Comme bello (Lucrezia) 8’ GAETANO DONIZETTI DON PASQUALE Quel guardo il cavaliere – So anch’io la virtu magica (Norina) 5’56 GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Della crudela Isotta (Adina – arie act 1) GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Prendi, per me sei libero (Adina – arie act 2) G.ROSSINI IL BARBIERE DI SEVILLA Una voce -

Mihail Jora Către Didia Saint Georges. Un Serial Epistolar Inedit

Revista MUZICA Nr. 2 / 2018 ISTORIOGRAFIE Mihail Jora către Didia Saint Georges Un serial epistolar inedit Lavinia Coman Au şi scrisorile soarta lor. Sunt 45 de ani de când maestrul Mihail Jora (1891-1971) a plecat din această lume şi 37 de ani de la dispariţia Didiei Saint Georges (1888-1979)1. Un pachet cu 18 scrisori şi două tăieturi de ziar au traversat deceniile pentru a ajunge în sfârşit, în lumina publică. Pe lângă originile moldovene comune, pe corespondenţi îi leagă câteva coordonate ale destinului. Dotaţi amândoi cu vocaţie muzicală, 1 Didia Saint Georges a fost pianistă şi compozitoare (1888, Botoşani – 1979, Bucureşti). A studiat la Conservatorul din Iaşi între 1905 -1907 şi la Conservatorul din Leipzig între 1907 – 1910 cu Robert Teichmüller -pianul, cu Emil Paul - armonia şi contrapunctul, cu Stephan Krell - compoziţia. A concertat ca solistă şi ca parteneră în recitaluri camerale, de lied etc. A primit Menţiune la Premiul de compoziţie George Enescu (1929) pentru Variaţiuni pe un cântec evreiesc; Menţiunea I la Premiul de compoziţie George Enescu (1930) pentru Suita De la musique avant toute chose; Menţiunea I onorifică la Premiul de compoziţie George Enescu (1943) pentru Sonatina pentru pian. A fost membră a Societăţii Compozitorilor Români din anul 1929. Lisette Georgescu, prietena lor comună, o evocă astfel în articolul său In memoriam Mihail Jora: ”Didia Saint Georges, compozitoare de talent,…dar care nu s-a dedicat serios compoziţiei, cu tot talentul ei rămânând la mijloc de drum. La un moment dat s-a ivit o gravă spărtură în prietenia lor dar, datorită Marianei Dumitrescu, preţuită şi iubită de Didia, conflictul s-a aplanat.” (Lisette Georgescu, In memoriam Mihail Jora, în Mihail Jora. -

Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET BY 2009 Cosmin Teodor Hărşian Submitted to the graduate program in the Department of Music and Dance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________ Chairperson Committee Members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended 04. 21. 2009 The Document Committee for Cosmin Teodor Hărşian certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ Advisor Date approved 04. 21. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Hărșian, Cosmin Teodor, Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2009. Romanian music during the second half of the twentieth century was influenced by the socio-politic environment. During the Communist era, composers struggled among the official ideology, synchronizing with Western compositional trends of the time, and following their own natural style. With the appearance of great instrumentalists like clarinetist Aurelian Octav Popa, composers began writing valuable works that increased the quality and the quantity of the repertoire for this instrument. Works written for clarinet during the second half of the twentieth century represent a wide variety of styles, mixing elements from Western traditions with local elements of concert and folk music. While the four works discussed in this document are demanding upon one’s interpretative abilities and technically challenging, they are also musically rewarding. iii I wish to thank Ioana Hărșian, Voicu Hărșian, Roxana Oberșterescu, Ilie Oberșterescu and Michele Abbott for their patience and support. -

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania Nicolae GHEORGHIță National University of Music, Bucharest Str. Ştirbei Vodă nr. 33, Sector 1, Ro-010102, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2015; accepted: September 2015) Abstract: In an atheist society, such as the communist one, all forms of the sacred were anathematized and fiercly sanctioned. Nevertheless, despite these ideological barriers, important articles and volumes of Byzantine – and sometimes Gregorian – musicological research were published in totalitarian Romania. Numerous Romanian scholars participated at international congresses and symposia, thus benefiting of scholarships and research stages not only in the socialist states, but also in places regarded as ‘affected by viruses,’ such as the USA or the libraries on Mount Athos (Greece). This article discusses the mechanisms through which the research on religious music in Romania managed to avoid ideological censorship, the forms of camouflage and dissimulation of musicological information with religious subject that managed to integrate and even impose over the aesthetic visions of the Party. The article also refers to cultural politics enthusiastically supporting research and valuing the heritage of ancient music as a fundamental source for composers and their creations dedicated to the masses. Keywords: Byzantine musicology, Romania, 1944–1990, socialist realism, totalitari- anism, nationalism Introduction In August 1948, only eight months after the forced abdication of King Michael I of Romania and the proclamation of the people’s republic (30 December 1947), the Academy of Religious Music – as part of the Bucharest Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, today the National University of Music – was abolished through Studia Musicologica 56/4, 2015, pp. -

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed

George Enescu, Posthumously Reviewed Va lentina SANDU-DEDIU National University of Music Bucharest Strada Știrbei Vodă 33, București, Ro-010102 Romania New Europe College Bucharest Strada Plantelor 21, București, Ro-023971 Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: November 2017; accepted: January 2018) Abstract: This essay tackles some aspects related to the attitude of the Romanian officials after George Enescu left his country definitively (in 1946). For example, re- cent research through the archives of the former secret police shows that Enescu was under the close supervision of Securitate during his last years in Paris. Enescu did not generate a compositional school during his lifetime, like for instance Arnold Schoen- berg did. His contemporaries admired him, but each followed their own path and had to adapt differently to an inter-war, then to a post-war, Communist Romania. I will therefore sketch the approach of younger composers in relation to Enescu (after 1955): some of them attempted to complete unfinished manuscripts; others were in fluenced by ideas of Enescu’s music. The posthumous reception of Enescu means also an in- tense debate in the Romanian milieu about his “national” and “universal” output. Keywords: Securitate, socialist realism in Romania, “national” and “universal,” het- erophony, performance practice It is a well-known fact that George Enescu did not create a school of composition during his lifetime, neither in the sense of direct professor–student transmission of information, as was the case in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg, nor in the wider sense of a community of ideas or aesthetic principles. His contemporaries admired him, but they each had their own, well-established stylistic paths; in the Stalinist post-war period, some of them subordinated their work to the ideological requirements of socialist realism and it was generally discouraged to discern the subtle, but substantial renewals of Enescu’s musical language. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Bollettino Novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci Dell'istituto Superiore Di Studi Musicali Di Reggio Emilia E Castelnovo Ne' Monti

Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti Stampato il 22/09/14 Parametri di ricerca comunicati: (Biblioteca: BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI ) AND (Categoria: Libro Moderno OR Categoria: Libro Antico OR Categoria: Audiovisivo OR Categoria: Musica OR Categoria: Materiale sonoro OR Categoria: Collana ) AND (Periodo di acquisizione: Ultimo semestre ) AND (InvSerieBiblio: ISS ) AND (Anno pubblicazione: 1990 OR Anno pubblicazione: 2014 ) AND (Tipologia: Registrazione sonora musicale OR Tipologia: Materiale video OR Tipologia: Video musicale ) Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti 1 [Materiale video] *Alice Mafessoni, flauto; Silvia Storchi, clarinetto; Silvia Ciammaglichella, pianoforte / musiche di J. Francaix, I. Stravinsky, J. S. Bach, F. Martin, J. Ibert. - San Martino in Rio : Villa Nostradamus, 2014. - 1 DVD ; 12 cm. ((Titolo del contenitore. - DVD realizzato in occasione dell'iniziativa "L'ora della musica" promossa dall'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti, sede "A. Peri", domenica 23 marzo 2014. Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9267 MEDIATECA DVD GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO OM 2014 0009 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 2 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Prélude : live recording Falaut campus / [musiche di] B. Godart, A. Dvorak, A. Bazzini, C. Debussy, F. Martin, F. Borne, J. Massenet ; Paolo Taballione, flauto ; Amedeo Salvato, pianoforte. - [Pompei] : Falaut, 2014. - 1 compact disc ; 12 cm. ((Allegato a: Falaut, gennaio-marzo 2014, n. 60. - Registrazione live: concerto del 22 agosto 2013, Sala Marte Mediateca [Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno]. (Falaut collection) Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9967 MEDIATECA CD D GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO 1050 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 3 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Jihoon Shin / [esegue musiche di] P. -

Constante Şi Deschideri În Cvartetele De Coarde Ale Lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I)

MUZICA nr.1/2010 CREAŢII Monica CENGHER Constante şi deschideri în cvartetele de coarde ale lui Wilhelm Georg Berger (I) Interesul lui W.G.Berger pentru genurile instrumentale verificate de proba îndelungată a istoriei, primordiale fiind cvartetul de coarde şi simfonia alături de concertul instrumental şi sonată, s-a concretizat într-o vastă operă de autor, elaborată în spiritul unui virtual dar ingenios dialog cu valorile supreme ale culturii. Sintagma goetheană “dacă vrei să păşeşti în infinit, parcurge finitul din toate direcţiile” este emblematică demersului său artistic. Vocaţia renascentistă de a iscodi concreteţea artei muzicale din mai multe ipostaze (istorice, estetice, matematice, componistice şi nu în ultimul rând interpretative), a fost dublată de însuşirile unei personalităţi profunde, înzestrată cu o fină inteligenţă, generozitate şi fire contemplativă cu nuanţe de blândeţe. “Fenomenul W. Berger – căci a fost un fenomen cu totul neobişnuit – nu s-a produs în locuri obscure sau ascunse, ci în plină lumină”1- releva pe un ton admirativ Pascal Bentoiu. Această forţă iradiantă însoţită de bucuria revelaţiei pe care i-a oferit-o cunoaşterea, l-au călăuzit întreaga viaţă, conturându-i opera de autor pe dimensiuni monumentale, masive şi de o anvergură nemaiîntâlnită la noi. Abundenţa cu care dădea la iveală creaţiile muzicale şi lucrările muzicologice reprezintă amplitudinea aspiraţiilor sale de largă cuprindere, în care erudiţia naşte imaginaţie şi detaliul se generalizează în concepte abstracte. Există o cadenţă în evoluţia lui W.G.Berger. Pe de o parte urmăreşte împlinirea unor ţeluri pe planul gândirii despre muzică, pornind de la analiza resorturilor intime ale fenomenului muzical, conturând liniile de forţă ale curentelor şi mentalităţilor artistice; pe de altă parte, se defineşte printr-o consistentă gândire componistică cu deschideri atât către tradiţii cât şi spre înnoiri. -

Pot Înţelege Motivul Pentru Care Scena Lirică Bucureşteană Şi-A

Pot înţelege motivul pentru care scena lirică bucureşteană şi-a înscris pe afişul celei dintâi premiere a anului 2009 spectacolul-coupe Go/em - Arald: Opera care s-a numit multă vreme "Română", iar acum este "Naţională", avea neapărată nevoie să-şi îmbogăţească urgent repertoriul autohton, cu deosebire precar. Pot înţelege şi de ce, pentru acest demers, a fost ales numele compozitorului Nicolae Bretan (1887-1968), muzician format la Cluj (1906-1 908) şi perfecţionat la Viena (1908-1909) şi Budapesta (1909-1 912), cântăreţ la Bratislava (1913-1914) şi Oradea (1914-1916), revenit în cele din urmă la Cluj, unde a fost, rând pe rând, solist şi regizor la Te atrul Maghiar (1917-1 922), prim-bariton (1922-1940), regizor (1922-1940, 1946-1 948) şi director (1944-1945) la Opera Română, regizor la Te atrul de Stat şi la Opera Maghiară (1940-1 944): chiar dacă valoarea acestui artist (cunoscut ca autor mai cu seamă graţie nenumăratelor sale lieduri) îl pla sează cu mult în urma confratilor mai vechi sau mai noi care s-au încumetat să scrie în pretenţiosul gen al dramei muzicale, alte avantaje - de ordin administrativ şi economic - îl făceau eligibil. Pot înţelege până şi faptul că, din creaţia lirica-dramatică a lui Nicolae Bretan, nu s-a optat pentru Luceafărul sau pentru Eroii de la Ravine (opere într-un act, dar cu mai multe tablouri), şi cu atât mai puţin pentru Horia (în trei acte!), ci pentru aceste două lucrări, nu numai concise, dar şi. .. sumare: decor unic, per sonaje (extrem de) puţine, cor absent (cu totul, în Arald; de pe scenă doar, -

Artes 21-22.Docx

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2020-0004 Artes. Journal of Musicology Constantin Silvestri, the problematic musician. New press documents ALEX VASILIU, PhD “George Enescu” National University of Arts ROMANIA∗ Abstract: Constantin Silvestri was a man, an artist who reached the peaks of glory as well as the depths of despair. He was a composer whose modern visions were too complex for his peers to undestand and accept, but which nevertheless stood the test of time. He was an improvisational pianist with amazing technique and inventive skills, and was obsessed with the score in the best sense of the word. He was a musician well liked and supported by George Enescu and Mihail Jora. He was a conductor whose interpretations of any opus, particularly Romantic, captivate from the very first notes; the movements of the baton, the expression of his face, even one single look successfully brought to life the oeuvres of various composers, endowing them with expressiveness, suppleness and a modern character that few other composers have ever managed to achieve. Regarded as a very promising conductor, a favourite with the audiences, wanted by the orchestras in Bucharest in the hope of creating new repertoires, Constantin Silvestri was nevertheless quite the problematic musician for the Romanian press. Newly researched documents reveal fragments from this musician’s life as well as the features of a particular time period in the modern history of Romanian music. Keywords: Romanian press; the years 1950; socialist realism. 1. Introduction The present study is not necessarily occasioned by the 50th anniversary of Constantin Silvestri’s death (23rd February 1969). -

III Nicolae Coman

Nicolae Coman (b. Bucharest, 23 February 1936 – d. Bucharest, 27 October 2016) The Seasons • Average duration: 67 min. • First performance: 26 March 2016, Cantacuzino Palace, Bucharest. With Emanuela Profirescu (piano) and Silviu Geamănu (reciter) Preface Nicolae Coman was born in 1936 in Bucharest. During his high-school years he began studying music privately with the renowned Romanian teachers: composer Mihail Jora and pianist Florica Musicescu. He took classes at the ”Ciprian Porumbescu” Conservatory in Bucharest with Mihail Jora and Leon Klepper (composition), Paul Constantinescu (harmony), Zeno Vancea and Miriam Marbé (counterpoint), Tudor Ciortea (form analysis), Victor Iusceanu (music theory), George Breazul (music history), Alfred Mendelsohn (orchestration), Emilia Comişel and Mariana Cahane (folk music), Ovidiu Drimba and Eugenia Ionescu (piano) and Mansi Barberis (canto). After his graduation he worked at the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company, but was not allowed to promote to an employee position due to political reasons, having to do with the clash between Coman’s family history and the socialist regime. Regardless of this he was permitted to collaborate with the national radio for many decades, for broadcasts and interviews. He worked as a researcher at the Folk Music Institute within the Romanian Academy, from 1959 – 1963. It was during this time that he travelled to villages in Pădureni (Hunedoara) to gather folk songs. Writing them down and analysing them led to his essay about the Romanian folk music in that region, Jocuri din ţinutul Pădureni. In 1963 he started teaching harmony (assisting Ion Dumitrescu’s class) and counterpoint at the Bucharest Conservatory. He held a professorship from 1992 until the end of his life, for the last 2 decades teaching composition as well. -

Transformations of Programming Policies

The Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Transformations of Programming Music Policies Małgorzata gąsiorowska Email: [email protected]???? Email: The Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music Transformations of Programming Policies Musicology today • Vol. 14 • 2017 DOI: 10.1515/muso-2017-0001 ABSTRACT situation that people have turned away from contemporary art because it is disturbing, perhaps necessarily so. Rather than The present paper surveys the history of the Warsaw Autumn festival confrontation, we sought only beauty, to help us to overcome the 1 focusing on changes in the Festival programming. I discuss the banality of everyday life. circumstances of organising a cyclic contemporary music festival of international status in Poland. I point out the relations between The situation of growing conflict between the bourgeois programming policies and the current political situation, which in the establishment (as the main addressee of broadly conceived early years of the Festival forced organisers to maintain balance between th Western and Soviet music as well as the music from the so-called art in the early 20 century) and the artists (whose “people’s democracies” (i.e. the Soviet bloc). Initial strong emphasis on uncompromising attitudes led them to question and the presentation of 20th-century classics was gradually replaced by an disrupt the canonical rules accepted by the audience and attempt to reflect different tendencies and new phenomena, also those by most critics) – led to certain critical situations which combining music with other arts. Despite changes and adjustments in marked the beginning of a new era in European culture. the programming policy, the central aim of the Festival’s founders – that of presenting contemporary music in all its diversity, without overdue In the history of music, one such symbolic date is 1913, emphasis on any particular trend – has consistently been pursued.