Studia Musica – 1 – 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

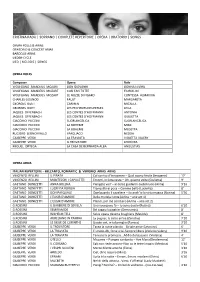

Soprano | Complete Repertoire | Opera | Oratorio | Songs

CRISTINA RADU | SOPRANO | COMPLETE REPERTOIRE | OPERA | ORATORIO | SONGS OPERA ROLES & ARIAS ORATORIO & CONCERT ARIAS BAROQUE ARIAS LIEDER-CYCLE LIED | MELODIE | SONGS OPERA ROLES Composer Opera Role WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART DON GIOVANNI DONNA ELVIRA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART COSI FAN TUTTE FIORDILIGI WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART LE NOZZE DI FIGARO CONTESSA ALMAVIVA CHARLES GOUNOD FAUST MARGARETA GEORGES BIZET CARMEN MICAELA GEORGES BIZET LES PECHEURS DES PERLES LEILA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN ANTONIA JAQUES OFFENBACH LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN GIULIETTA GIACOMO PUCCINI SUOR ANGELICA SUOR ANGELICA GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MIMI GIACOMO PUCCINI LA BOHEME MUSETTA RUGIERO LEONCAVALLO I PAGLIACCI NEDDA GIUSEPPE VERDI LA TRAVIATA VIOLETTA VALERY GIUSEPPE VERDI IL TROVATORE LEONORA MIGUEL ORTEGA LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA ANGUSTIAS OPERA ARIAS ITALIAN REPERTOIRE – BELCANTO, ROMANTIC & VERISMO ARIAS ARIAS VINCENZO BELLINI IL PIRATA Col sorriso d’innocenza – Qual suono ferale (Imogene) 12’ VINCENZO BELLINI MONTECCHI I CAPULETTI Eccomi, in lieta vesta – Oh, quante volte (Giulietta) 9’ GAETANO DONIZETTI ANNA BOLENA Piangete voi? – al dolce guidarmi castel natio (Anna) 9’16 GAETANO DONIZETTI LUCREZIA BORGIA Tranquillo ei posa – Comme bello (Lucrezia) 8’ GAETANO DONIZETTI DON PASQUALE Quel guardo il cavaliere – So anch’io la virtu magica (Norina) 5’56 GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Della crudela Isotta (Adina – arie act 1) GAETANO DONIZETTI L’ELISIR D’AMORE Prendi, per me sei libero (Adina – arie act 2) G.ROSSINI IL BARBIERE DI SEVILLA Una voce -

Act Aditional Modificare Statut

Asociaţia de Dezvoltare Intercomnitară Anexa nr. 1. la Hotărârea AGA nr. 17 din 17.12.2012. de Utilităţi Publice „ECO SEPSI” Sf. Gheorghe str. Energiei nr. 2, jud. Covasna Nr. şi data înscrierii în Registrul Special: 9 din 25.06.2009. Nr. 63 din 17.12.2012. ACT ADIŢIONAL NR. 2 / 17.12.2012. LA STATUTUL Asociaţiei de dezvoltare intercomunitară de utilităţi publice „ECO SEPSI” Asociaţii 1. Municipiul Sfântu Gheorghe, prin Consiliul Local Sfântu Gheorghe, cu sediul în mun. Sfântu Gheorghe, str. 1. Decembrie 1918, nr. 2, judeţul Covasna, CIF 4404605, cont RO09TREZ2564670220XXXXX, deschis la Trezorăria mun. Sf. Gheorghe, reprezentat de Antal Árpád-András, în calitate de primar; 2. Comuna Chichis, prin Consiliul Local Chichiş, cu sediul în localitatea Chichiş, str. Mare, nr. 103, judeţul Covasna, CIF 4201899, cont RO78TREZ2565040XXX000288, deschis la Trezorăria mun. Sf. Gheorghe, reprezentat de Santa Gyula, în calitate de primar; 3. Comuna Ilieni, prin Consiliul Local Ilieni, cu sediul în localitatea Ilieni, str Kossuth Lajos, nr. 97, judeţul Covasna, CIF 4404419, cont RO13TREZ25624510220XXXXX, deschis la Trezorăria mun. Sf. Gheorghe, reprezentat de Fodor Imre, în calitate de primar; 4. Comuna Dobârlău prin Consiliul Local Dobârlău, cu sediul în comuna Dobârlău, satul Dobârlău nr. 233, judeţul Covasna, CIF 4404575 cont. RO97TREZ2565040XXX003535, deschis la Trezoreria mun. Sf. Gheorghe, reprezentat de Maxim Vasile, în calitate de primar; 5. Comuna Arcuş prin Consiliul Local Arcuş, cu sediul în comuna Arcuş P-ţa Gábor Áron nr. 237, judeţul Covasna, CIF 16318699 cont. RO44TREZ25624740255XXXXX, deschis la Trezoreria mun. Sf. Gheorghe, reprezentat de Máthé Árpád, în calitate de primar; 6. Comuna Vâlcele prin Consiliul Local Vălcele, cu sediul în comuna Vâlcele, satul Araci str. -

Consideraţii Litostratigrafice Şi Hidrogeologice Privind

ANALELE ŞTIINŢIFICE ALE UNIVERSITĂŢII ”AL. I. CUZA“ IAŞI Geologie. Tomul LI, 2005 LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC AND HYDROGEOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING PLIOCENE-QUATERNARY DEPOSITS FROM SFANTU GHEORGHE AND TARGU SECUIESC SEDIMENTARY DEPRESSIONS, ROMANIA RODICA MACALEŢ, EMIL RADU, RADU CATALINA1 SUMMARY The paper presents some lithostratigraphic and hydrogeologic considerations of Neogene and Quaternary deposits from Sfântu Gheorghe and Târgu Secuiesc depressions, based on information from recent drilling programme. Several hydrogeological cross-sections are presented here to support the geological interpretation and tectonic evolution of the Pliocene-Quaternary deposits in the area. Key words: lithostratigraphy, hydrogeology, Sfântu Gheorghe depression, Târgu Secuiesc depression, groundwater, aquifer strata. INTRODUCTION Starting from Pliocene, the tectonic evolution of the Sfântu Gheorghe and Târgu Secuiesc depressions was favourable for developement of molasse deposits, with high lithological variability and conditions for lignite layers accumulation. This paper is based on new information obtained from water bores, geological drillholes and also from drillholes mainly drilled to assess the potential for the presence of new lignite layers in the area, with emphasis on geology and faunal content of the Pliocene and Quaternary sediments. A number of drillholes from Sfantu Gheorghe and Targu Secuiesc depressions have been investigated by the author. The results are present using several cross-sections and synthetic lithostratigraphic columns, which provide a new base to interpret the geology of the area as well as the groundwater potential. 139 Rodica Macaleţ, Emil Radu, Cătălina Radu GENERAL GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE AREA Based on their geomorphology, Sfântu Gheorghe and Târgu Secuiesc depressions are considered to be part of the Braşov Basin, and are developed on its north-eastern side. -

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania Nicolae GHEORGHIță National University of Music, Bucharest Str. Ştirbei Vodă nr. 33, Sector 1, Ro-010102, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2015; accepted: September 2015) Abstract: In an atheist society, such as the communist one, all forms of the sacred were anathematized and fiercly sanctioned. Nevertheless, despite these ideological barriers, important articles and volumes of Byzantine – and sometimes Gregorian – musicological research were published in totalitarian Romania. Numerous Romanian scholars participated at international congresses and symposia, thus benefiting of scholarships and research stages not only in the socialist states, but also in places regarded as ‘affected by viruses,’ such as the USA or the libraries on Mount Athos (Greece). This article discusses the mechanisms through which the research on religious music in Romania managed to avoid ideological censorship, the forms of camouflage and dissimulation of musicological information with religious subject that managed to integrate and even impose over the aesthetic visions of the Party. The article also refers to cultural politics enthusiastically supporting research and valuing the heritage of ancient music as a fundamental source for composers and their creations dedicated to the masses. Keywords: Byzantine musicology, Romania, 1944–1990, socialist realism, totalitari- anism, nationalism Introduction In August 1948, only eight months after the forced abdication of King Michael I of Romania and the proclamation of the people’s republic (30 December 1947), the Academy of Religious Music – as part of the Bucharest Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, today the National University of Music – was abolished through Studia Musicologica 56/4, 2015, pp. -

Harmonizing State- and EU-Funded Projects in Regions | Final Synthesis Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized Harmonizing STATE- AND EU-FUNDED PROJECTS in Regions | Final Synthesis Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Agreement for Harmonizing State- and EU-funded Final Investment Programs Romania Regional Development Program 2 Synthesis Dated November 26, 2015 Project co-financed from the European Regional Development Fund through the Operational Programme Technical Assistance (OPTA) 2007-2013 Agreement for Advisory Services on Assistance to the Romanian Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration on Harmonizing State- and EU- funded Projects in Regions Final Synthesis November 26, 2015 Romania Regional Development Program 2 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ iii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. iv List of Boxes .............................................................................................................................................. iv List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................ v Sumary ........................................................................................................................................................ -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Bollettino Novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci Dell'istituto Superiore Di Studi Musicali Di Reggio Emilia E Castelnovo Ne' Monti

Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti Stampato il 22/09/14 Parametri di ricerca comunicati: (Biblioteca: BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI ) AND (Categoria: Libro Moderno OR Categoria: Libro Antico OR Categoria: Audiovisivo OR Categoria: Musica OR Categoria: Materiale sonoro OR Categoria: Collana ) AND (Periodo di acquisizione: Ultimo semestre ) AND (InvSerieBiblio: ISS ) AND (Anno pubblicazione: 1990 OR Anno pubblicazione: 2014 ) AND (Tipologia: Registrazione sonora musicale OR Tipologia: Materiale video OR Tipologia: Video musicale ) Bollettino novità Biblioteca Armando Gentilucci dell'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti 1 [Materiale video] *Alice Mafessoni, flauto; Silvia Storchi, clarinetto; Silvia Ciammaglichella, pianoforte / musiche di J. Francaix, I. Stravinsky, J. S. Bach, F. Martin, J. Ibert. - San Martino in Rio : Villa Nostradamus, 2014. - 1 DVD ; 12 cm. ((Titolo del contenitore. - DVD realizzato in occasione dell'iniziativa "L'ora della musica" promossa dall'Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali di Reggio Emilia e Castelnovo ne' Monti, sede "A. Peri", domenica 23 marzo 2014. Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9267 MEDIATECA DVD GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO OM 2014 0009 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 2 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Prélude : live recording Falaut campus / [musiche di] B. Godart, A. Dvorak, A. Bazzini, C. Debussy, F. Martin, F. Borne, J. Massenet ; Paolo Taballione, flauto ; Amedeo Salvato, pianoforte. - [Pompei] : Falaut, 2014. - 1 compact disc ; 12 cm. ((Allegato a: Falaut, gennaio-marzo 2014, n. 60. - Registrazione live: concerto del 22 agosto 2013, Sala Marte Mediateca [Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno]. (Falaut collection) Biblioteca Inventario Collocazione BIBLIOTECA ARMANDO ISS 9967 MEDIATECA CD D GENTILUCCI DELL'ISTITUTO 1050 SUPERIORE DI STUDI MUSICALI 3 [Registrazione sonora musicale] *Jihoon Shin / [esegue musiche di] P. -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Cinema Ritrovato Di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk

Cinema Ritrovato di Gian Luca Farinelli, Vittorio Martinelli, Nicola Mazzanti, Mark-Paul Meyer, Ruud Visschedijk Iniziamo dalla foto che abbiamo scelto per il manifesto, perché è un’immagine rivelatrice dell’identità di questo festival. Ad un primo sguardo non suscita un interesse particolare. È la foto di scena di un film qualsiasi prodotto in un periodo in cui di cinema se ne faceva tanto, un’immagine come tante. Però se la guardiamo meglio vediamo che al centro della foto c’è uno dei grandi attori del cinema italiano, Aldo Fabrizi, il Don Pietro di Roma città aperta, alle prese con la giustizia. Ci accorgiamo anche che il set è il lato sud di Piazza Maggiore; si scorgono il Palazzo del Podestà, San Petronio, il Nettuno, Palazzo de’ Banchi. L’immagine inizia a intrigarci. Siccome il cinema italiano è da sempre fortemente romano, pochissimi sono stati i film girati a Bologna, almeno sino agli anni ’60. Ecco perché Hanno rubato un tram, il film da cui abbiamo sottratto quest’immagine, è una vera scoperta che ci giunge dal passato. Nonostante si tratti di una piccola produzione, di un film modesto, di cui all’epoca nessuno si accorse, poterlo vedere oggi è un’esperienza straordinaria perché ci porta nella Bologna di quarantasei anni fa e ci fa sentire tutta la distanza del tempo, le dimensioni della trasformazione, l’ampiezza dei cambiamenti, esperienza tanto più forte perché si tratta di immagini inaspettate di un film dimenticabile, che nessuno vedeva più da decenni. Il film è anche un curioso incontro tra generazioni diverse del cinema italiano. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

NEWSLETTER Editor: Francis Knights

NEWSLETTER Editor: Francis Knights Volume v/1 (Spring 2021) Welcome to the NEMA Newsletter, the online pdf publication for members of the National Early Music Association UK, which appears twice yearly. It is designed to share and circulate information and resources with and between Britain’s regional early music Fora, amateur musicians, professional performers, scholars, instrument makers, early music societies, publishers and retailers. As well as the listings section (including news, obituaries and organizations) there are a number of articles, including work from leading writers, scholars and performers, and reports of events such as festivals and conferences. INDEX Interview with Bruno Turner, Ivan Moody p.3 A painted villanella: In Memoriam H. Colin Slim, Glen Wilson p.9 To tie or not to tie? Editing early keyboard music, Francis Knights p.15 Byrd Bibliography 2019-2020, Richard Turbet p.20 The Historic Record of Vocal Sound (1650-1829), Richard Bethell p.30 Collecting historic guitars, David Jacques p.83 Composer Anniversaries in 2021, John Collins p.87 v2 News & Events News p.94 Obituaries p.94 Societies & Organizations p.95 Musical instrument auctions p.96 Conferences p.97 Obituary: Yvette Adams, Mark Windisch p.98 The NEMA Newsletter is produced twice yearly, in the Spring and Autumn. Contributions are welcomed by the Editor, email [email protected]. Copyright of all contributions remains with the authors, and all opinions expressed are those of the authors, not the publisher. NEMA is a Registered Charity, website http://www.earlymusic.info/nema.php 2 Interview with Bruno Turner Ivan Moody Ivan Moody: How did music begin for you? Bruno Turner: My family was musical. -

Pot Înţelege Motivul Pentru Care Scena Lirică Bucureşteană Şi-A

Pot înţelege motivul pentru care scena lirică bucureşteană şi-a înscris pe afişul celei dintâi premiere a anului 2009 spectacolul-coupe Go/em - Arald: Opera care s-a numit multă vreme "Română", iar acum este "Naţională", avea neapărată nevoie să-şi îmbogăţească urgent repertoriul autohton, cu deosebire precar. Pot înţelege şi de ce, pentru acest demers, a fost ales numele compozitorului Nicolae Bretan (1887-1968), muzician format la Cluj (1906-1 908) şi perfecţionat la Viena (1908-1909) şi Budapesta (1909-1 912), cântăreţ la Bratislava (1913-1914) şi Oradea (1914-1916), revenit în cele din urmă la Cluj, unde a fost, rând pe rând, solist şi regizor la Te atrul Maghiar (1917-1 922), prim-bariton (1922-1940), regizor (1922-1940, 1946-1 948) şi director (1944-1945) la Opera Română, regizor la Te atrul de Stat şi la Opera Maghiară (1940-1 944): chiar dacă valoarea acestui artist (cunoscut ca autor mai cu seamă graţie nenumăratelor sale lieduri) îl pla sează cu mult în urma confratilor mai vechi sau mai noi care s-au încumetat să scrie în pretenţiosul gen al dramei muzicale, alte avantaje - de ordin administrativ şi economic - îl făceau eligibil. Pot înţelege până şi faptul că, din creaţia lirica-dramatică a lui Nicolae Bretan, nu s-a optat pentru Luceafărul sau pentru Eroii de la Ravine (opere într-un act, dar cu mai multe tablouri), şi cu atât mai puţin pentru Horia (în trei acte!), ci pentru aceste două lucrări, nu numai concise, dar şi. .. sumare: decor unic, per sonaje (extrem de) puţine, cor absent (cu totul, în Arald; de pe scenă doar,