Finding Commission on May 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Date Range Organizational Body Subjects Formats General Description of Publication 1976-1995 Prairie Fire Organizing Prison, Political Prisoners, Human Rights, Black liberation, Periodicals, Publications by John Brown Book Club include Breakthrough, Committee/John Brown Book Chicano, Education, Gay/Lesbian, Immigration, Indigenous pamphlets political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC), Club struggle, Middle East, Militarism, National Liberation, Native published from 1977 to 1995; other documents published by American, Police, Political Prisoners, Prison, Women, AIDS, PFOC Anti-imperialism, Anti-racism, Anti-war, Apartheid, Aztlan, Black August, Clandestinity, COINTELPRO, Colonialism, Gender, High School, Kurds, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Feminism, Gentrification, Haiti, Israel, Nicaragua, Palestine, Puerto Rico, Racism, Resistance, Soviet Union/Russia, Zimbabwe, Philippines, Male Supremacy, Weather Underground Organization, Namibia, East Timor, Environmental Justice, Bosnia, Genetic Engineering, White Supremacy, Poetry, Gender, Environment, Health Care, Eritrea, Cuba, Burma, Hawai'i, Mexico, Religion, Africa, Chile, For other information about Prairie Fire Organizing Committee see the website pfoc.org [doesn't exist yet]. Freedom Archives [email protected] DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Keywords Azania, Torture, El Salvador, -

All Student Groups 2018-2019.Pdf

Group Name Governing Board 2018‐2019 Advisor 2018‐2019 Advisor E‐mail 180 Degrees Consulting SGB ‐ 4560315 Kyrena Wright [email protected] 4x4 Magazine ABC ‐ 4560313 Veronica Baran [email protected] Active Minds SGB ‐ 4560315 John Rowell [email protected] Activities Board at Columbia ABC ‐ 4560313 Kyrena Wright [email protected] Adventist Christian Fellowship (ACF) SGB ‐ 4560315 Divya Sharma [email protected] African Development Group SGB ‐ 4560315 Jacquis Watters [email protected] African Students Association* ABC ‐ 4560313 Jacquis Watters [email protected] Alexander Hamilton Society SGB ‐ 4560315 Michaelangelo Misseri [email protected] Alianza ABC ‐ 4560313 Ileana Casellas‐Katz [email protected] AllSex ABC ‐ 4560313 Avi Edelman [email protected] Alpha Chi Omega IGC‐ 4560309 Ryan Cole [email protected] Alpha Delta Phi IGC‐ 4560309 Ryan Cole [email protected] Alpha Epsilon Pi IGC‐ 4560309 Yvonne Pitts [email protected] Alpha Omega SGB ‐ 4560315 Divya Sharma [email protected] Alpha Omicron Pi IGC‐ 4560309 Yvonne Pitts [email protected] Alpha Phi Alpha IGC‐ 4560309 Yvonne Pitts [email protected] American Enterprise Institute @ Columbia (AEI) SGB ‐ 4560315 Marnie Whalen [email protected] American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics ABC ‐ 4560313 Michaelangelo Misseri [email protected] American Institute of Chemical Engineers ABC ‐ 4560313 Jacquada Gray [email protected] American Medical Students Association ABC ‐ 4560313 Ben Jones [email protected] American Society of Civil -

Chronology of Events

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ll quotes are from Spectator, Columbia’s student-run newspaper, unless otherwise specifed. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia A .edu/. Some details that follow are from Up Against the Ivy Wall, edited by Jerry Avorn et al. (New York: Atheneum, 1969). SEPTEMBER 1966 “After a delay of nearly seven years, the new Columbia Community Gymnasium in Morningside Park is due to become a reality. Ground- breaking ceremonies for the $9 million edifice will be held early next month.” Two weeks later it is reported that there is a delay “until early 1967.” OCTOBER 1966 Tenants in a Columbia-owned residence organize “to protest living condi- tions in the building.” One resident “charged yesterday that there had been no hot water and no steam ‘for some weeks.’ She said, too, that Columbia had ofered tenants $50 to $75 to relocate.” A new student magazine—“a forum for the war on Vietnam”—is pub- lished. Te frst issue of Gadfy, edited by Paul Rockwell, “will concentrate on the convictions of three servicemen who refused to go to Vietnam.” This content downloaded from 129.236.209.133 on Tue, 10 Apr 2018 20:25:33 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms LII CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS Te Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) orga- nizes a series of workshops “to analyze and change the social injustices which it feels exist in American society,” while the Independent Commit- tee on Vietnam, another student group, votes “to expand and intensify its dissent against the war in Vietnam.” A collection of Columbia faculty, led by Professor Immanuel Wallerstein, form the Faculty Civil Rights Group “to study the prospects for the advancement of civil rights in the nation in the coming years.” NOVEMBER 1966 Columbia Chaplain John Cannon and ffeen undergraduates, including Ted Kaptchuk, embark upon a three-day fast in protest against the war in Vietnam. -

Deposit and Copying Declaration Form

The Life of the Mind: An Intellectual Biography of Richard Hofstadter Andrew Ronald Snodgrass Jesus College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2018 Abstract The Life of the Mind: An Intellectual Biography of Richard Hofstadter Andrew Ronald Snodgrass Despite his death in 1970, Richard Hofstadter’s work continues to have an enduring influence in American political culture. Yet despite the continued and frequent use of his interpretations in public discourse, his reputation within historical scholarship remains, to a large degree, shaped by perceptions that were formed towards the end of his career. The narrative pervades of Hofstadter as the archetypal New York intellectual who rejected his youthful radicalism for political conservatism which, in turn, shaped his consensus vision of the past. These assessments reflect the biographical tendency to read a life and career backwards. From such a vantage point, Hofstadter’s work is viewed through the prism of his perceived final position. My dissertation challenges the accepted narrative by considering his writing in the context of the period of time in which it was written. In doing so, it is evident that his work belies attempts to reduce his scholarship to reflections of a shifting political standpoint. Whilst it is undoubted that Hofstadter’s historical and political view changed through time, there was a remarkable consistency to his thought. Throughout his career, his writing and lectures were suffused with a sense of the contingency of truth. It was the search for new uncertainties rather than the capture of truth which was central to his work. -

Columbia Blue Great Urban University

Added 3/4 pt Stroke From a one-room classroom with one professor and eight students, today’s Columbia has grown to become the quintessential Office of Undergraduate Admissions Dive in. Columbia University Columbia Blue great urban university. 212 Hamilton Hall, MC 2807 1130 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10027 For more information about Columbia University, please call our office or visit our website: 212-854-2522 undergrad.admissions.columbia.edu Columbia Blue D3 E3 A B C D E F G H Riverside Drive Columbia University New York City 116th Street 116th 114th Street 114th in the City of New York Street 115th 1 1 Columbia Alumni Casa Center Hispánica Bank Street Kraft School of Knox Center Education Union Theological New Jersey Seminary Barnard College Manhattan School of Music The Cloisters Columbia University Museum & Gardens Subway 2 Subway 2 Broadway Lincoln Center Grant’s Tomb for the Performing Arts Bookstore Northwest Furnald Lewisohn Mathematics Chandler Empire State Washington Heights Miller Corner Building Hudson River Chelsea Building Alfred Lerner Theatre Pulitzer Earl Havemeyer Clinton Carman Hall Cathedral of Morningside Heights Intercultural Dodge Statue of Liberty West Village Flatiron Theater St. John the Divine Resource Hall Dodge Fitness One World Trade Building Upper West Side Center Pupin District Center Center Greenwich Village Jewish Theological Central Park Harlem Tribeca 110th Street 110th 113th Street113th 112th Street112th 111th Street Seminary NYC Subway — No. 1 Train The Metropolitan Midtown Apollo Theater SoHo Museum of Art Sundial 3 Butler University Teachers 3 Low Library Uris Schapiro Washington Flatiron Library Hall College Financial Chinatown Square Arch District Upper East Side District East Harlem Noho Gramercy Park Chrysler College Staten Island New York Building Walk Stock Exchange Murray Lenox Hill Yorkville Hill East Village The Bronx Buell Avery Fairchild Lower East Side Mudd East River St. -

U:\WPWIN\Electronic Finding Aids\Marshall Mcluhan.Wpd

Manuscript Division des Division manuscrits H. MARSHALL McLUHAN MG 31, D 156 Finding Aid No. 1645 / Instrument de recherche no 1645 Prepared in 1987 by staff of the Social and Cultural Archives. Revised in 1988, 1991, 1997 and 2000. Préparé en 1987 par le personnel des Archives sociales et culturelles. Révisé en 1988, 1991, 1997 et 2000. TABLE OF CONTENTS Personal and Family Series .....................................................1 Articles about McLuhan .................................................10 Correspondence Series .......................................................42 Nominal Correspondence .................................................42 Fan and Crank Mail....................................................146 Invitations to Lecture (Part One)..........................................148 Invitations to Lecture (Part Two)..........................................167 Recommendations .....................................................169 Manuscripts Series ..........................................................181 Books ...............................................................181 "The Place of Thomas Nashe in the Learning of his Time" ...............181 Prelude to Prufrock ..............................................189 [Character Anthology]............................................190 The New American Vortex .........................................191 The Mechanical Bride ............................................193 Counterblast ....................................................209 Selected Poetry -

THE BLUE and WHITE Vol

THE BLUE AND WHITE Vol. VII, No. I September 2000 Columbia College, New York NY <SE> THE CULT OF THE COLUMBIA PROFESSOR by Dimitri Portnoi VENDING MACHINES REVIEWED THE LIVING LEGACIES PROJECT by Mariel L. Woljson An Introduction by Prof. Wm. Theodore de Bary Columns 3 I ntroduction 7 B l u e J 14 M e a s u r e f o r M e a s u r e 16 T o l d B e t w e e n P u f f s 21 C u r i o C o l u m b i a n a 22 C a m p u s G o s s ip Features 4 “Living Legacies” Introduced 9 The Cult of the Professor 11 Vending Machines Reviewed 17 “A Clearing in the Distance” 19 Volunteering Guide * About the Cover: “Apotheosis” by Matthew Rascoff Graphics by: Clare H. Ridley; Barbarossa $ T ypographical N o t e The text of The Blue and IVhite is set in Bodoni Old Face, which was designed by ^2 j Günter Gerhard Lange for Berthold. The dis play faces are Weiss, created by Rudolf Weiss T he B lu e a n d W h ite THE BLUE AND WHITE V o l. V II N ew Y o r k, S eptem ber aooo No. I THE BLUE AND WHITE University archive located in Low Library. The magazine’s mission, as expressed by Editor Editor-in-Chief Sydney Treat C’1893, was: MATTHEW RASCOFF, C’Ol to give bright and newsy items, which are of inter Publisher est to all of us, combined with truthful comments on the same, in order to show clearly the exact tone of C. -

INTERVIEWS with KWAME TUR£ (Stoldy Carmichael) and Chokwe Luwumba Table of Contents

. BLACK LIBERATION 1968 - 1988 INTERVIEWS wiTh KWAME TUR£ (SToldy CARMichAEl) ANd ChokwE LuwuMbA Table of Contents 1 Editorial: THE UPRISING 3 WHAT HAPPENS TO A DREAM DEFERRED? 7 NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE-The Black Liberation Movement 1968-1988 Interview with Chokwe Lumumba, Chairman, New Afrikan People's Organization Interview with Kwame Ture", All-African People's Revolutionary Party 17 FREE THE SHARPEVILLE SIX ™"~~~~~~~ 26 Lesbian Mothers: ROZZIE AND HARRIET RAISE A FAMILY —— 33 REVISING THE SIXTIES Review of Todd Gitlin's The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage 38 BEHIND THE U.S. ECONOMIC DECLINE by Julio Rosado, Movimiento de Liberaci6n Nacional Puertorriquefio 46 CAN'T KILL THE SPIRIT ~ Political Prisoners & POWs Update 50 WRITE THROUGH THE WALLS Breakthrough, the political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, is published by the John Brown Book Club, PO Box 14422, San Francisco, CA 94114. This is Volume XXII, No. 1, whole number 16. Press date: June 21,1988. Editorial Collective: Camomile Bortman Jimmy Emerman Judy Gerber Judith Mirkinson Margaret Power Robert Roth Cover photo: Day of Outrage, December 1987, New York. Credit: Donna Binder/Impact Visuals We encourage our readers to write us with comments and criticisms. You can contact Prairie Fire Oganizing Committee by writing: San Francisco: PO Box 14422, San Francisco, CA 94114 Chicago: Box 253,2520 N. Lincoln, Chicago, IL 60614 Subscriptions are available from the SF address. $6/4 issues, regular; $15/yr, institutions. Back issues and bulk orders are also available. Make checks payable to John Brown Book Club. John Brown Book Club is a project of the Capp St. -

Columbia University Department of Art History

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY MIRIAM AND IRA D. WALLACH FINE ARTS CENTER 826 FALL 2009 schermerhorn new faculty from the chairman’s office Kaira Cabañas The academic year that has just passed was marked by conferences and symposia that brought visitors to Schermerhorn Hall who became, at least for a short while, members of our shared intellectual enterprise. In The Department is pleased to welcome October, a conference organized by former students of David Rosand— Kaira Cabañas as Lecturer and Director a “Rosand Fest” as it was known informally—honored his final year of of the MA in Modern Art: Critical and teaching, and attracted a distinguished audience of art historians from Curatorial Studies. Cabañas, no stranger to the New York area and beyond. A major student-organized conference the Department, was a Mellon Postdoctoral on the visual culture of the nineteenth century held in April capped the Teaching Fellow from 2007 to 2009 after year with a two-day event at which Professor Jonathan Crary delivered completing a PhD in art history at Princeton University in the closing address. Other symposia organized by students explored the spring of 2007. Currently, she is preparing her first topics as varied as Chinese stone inscriptions and the relationship monograph, Performative Realisms: The Politics of Art and between contemporary art and media. Culture in France 1945–1962. Cabañas has also engaged Giving our students the opportunity to conceive and plan such extensively with modern and contemporary art in interna- ambitious events enriches their experience of being at Columbia. tional contexts. -

The Weather Underground Report Committee on The

94TH CoNobasg let eeio#8 00MMITTEN PRINT THE WEATHER UNDERGROUND REPORT OF TH7 SUBCOMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS OF THn COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JANUARY 1975 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OF110 39-242 WASHINGTON : 1975 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.8. Government Prnting Office, Waohington, D.C. 2040a Pice $1.60 jJ54QC~ -.3 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES 0. EASTLAND, MIsisppi, Chbaimon JOHIN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ROMAN L. 71 It USKA, Nebraska PHILIP A. HART, Michigan III RAM L. FONO0, Hawali EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Mamaohusmtts H1UOH SCOTT, Pennsylvania BIRCH BAYH, Indiana STROM TiUItMON D, South Carolina QUENTIN N. BURDICK, Nmth Dakota CIJA RLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., Maryland ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia WILLIAM L. 8('OTT, Virginia JOHN V. TUNNEY, California JAMES ABOUREZK, South Dakota SUnCOMMiTTIv To INVKSTIOATH TIe ADMINISTrATION o0 THE, INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS JAMES 0. EASTLAN ), MAisissdppi, Chairman JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkanras STROM TIHURMOND, South Carolina BIRCH BAYJI. Indiana J. 0. SOURWINH, Chief Cownsel ALYONUO L. TARADOCHIIA, Chief InIVtesgalor MARY DOOLEY, Adcng Director of Research RESOLUTION Resolved, by the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, that the attached report entitled "The Weather Underground," shall be printed for the use of the Com- mnittee on the Judiciary. JAMES 0. EASTLAND, Chairman. Approved: January 30, 1975. (n) CONTENTS Pan Foreword ......................................................... v The Weatherman Organization 1 Overview ......................................................... 1 Weatherman Political Theory-----------------------------. 9 Weatherman Chronology ........................................... 13 National War Council .....---------------------------- 20 The Faces of Weatherman Underground ............................ -

Baron, Salo W. Papers, Date (Inclusive): 1900-1980 Collection Number: M0580 Creator: Baron, Salo W

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft509nb07b No online items Guide to the Salo W. Baron Papers, 1900-1980 Processed by Polly Armstrong, Patricia Mazón, Evelyn Molina, Ellen Pignatello, and Jutta Sperling; reworked July, 2011 by Bill O'Hanlon Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Salo W. Baron M0580 1 Papers, 1900-1980 Guide to the Salo W. Baron Papers, 1900-1980 Collection number: M0580 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Polly Armstrong, Patricia Mazón, Evelyn Molina, Ellen Pignatello, and Jutta Sperling; reworked July, 2011 by Bill O'Hanlon Date Completed: 1993 June Encoded by: Sean Quimby © 2002 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Baron, Salo W. Papers, Date (inclusive): 1900-1980 Collection number: M0580 Creator: Baron, Salo W. Extent: ca. 398 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Abstract: The Baron Papers comprise the personal, professional, and research material of Salo Baron and occupy approximately 398 linear feet. As of July 1992 the papers total 714 boxes and are arranged in 11 series, including correspondence, personal/biographical, archival materials, subject, manuscripts, notecards, pamphlets, reprints, and books, manuscripts (other authors), notes, photo and audio-visual. -

CCR Annual Report 2012

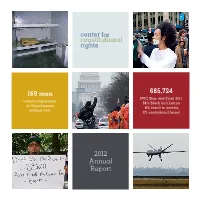

169 men 685,724 NYC Stop and Frisk 2011 remain imprisoned 84% Black and Latino at Guantánamo 6% result in arrests without trial 2% contraband found 2012 Annual Report The Center for Constitutional Rights is dedicated to advancing and protecting the rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Founded in 1966 by attorneys who represented civil rights movements in the South, CCR is a non-profit legal and educational organization committed to the creative use of law as a positive force for social change. www.CCRjustice.org table of contents Letter from the Executive Director ........................................................................................ 2 Guantánamo .............................................................................................................................. 4 International Human Rights ................................................................................................... 8 Government Misconduct and Racial Injustice ................................................................ 12 Movement Support .................................................................................................................. 16 Social Justice Institute ........................................................................................................... 18 Communications .................................................................................................................... 20 Letter from the Legal Director .............................................................................................