Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Symposium For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobbie Rosenfeld: the Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin

2005 GOLDEN OAK BOOK CLUB™ SELECTIONS Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin BOOK SUMMARY: Not so long ago, girls and women were discour- aged from playing games that were competitive and rough. Well into the 1950s, there was gen- der discrimination in sports. Girls were consid- ered too fragile and sensitive to play hard and to play well. But one woman astonished everyone. In fact, sportswriters and broadcasters in this country agree that Bobbie Rosenfeld may be Canada’s all-round greatest athlete of the twen- tieth century. Bobbie excelled at hockey, bas- ketball, softball, and track and field, and she became one of Canada’s first female Olympic medallists. Just as remarkable as her talent was her extraordinary sense of fair play. She greeted obstacles with courage, hard work, and a sense of humor, and she always put the team ahead of herself. In doing so, Bobbie set an example as a true athletic hero. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY: Like Bobbie Rosenfeld, Anne Dublin came to Canada at a young age. She worked as an elementary school teacher for over 25 years, and taught in Kingston, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Nairobi. During her writing career, Anne has written short stories, articles, poetry, and a novel called Written on the Wind. Anne currently works as a teacher- librarian in Toronto. Ontario Library Association Reading Programs ©2002-2005. Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin Suggestions for Tutors/Instructors 6. Why did sports become more popular with women? Before starting to read the story, read (aloud) the outside 7. -

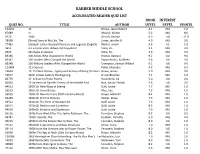

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Download This Page As A

Historica Canada Education Portal Bobbie Rosenfeld Overview This lesson is based on viewing the Bobbie Rosenfeld biography from The Canadians series. Rosenfeld won several medals at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, the first time women were permitted to compete in track and field events. The lesson explores Rosenfeld's career and the level of acceptance for female athletes in the 1920's. Aims In a variety of creative activities, students will assess and evaluate Rosenfeld's accomplishments while considering both the historic and comtemporary role of women in competitive sport. Background "Miss Rosenfeld, who never had a coach, was that rarity, a natural athlete." -Globe and Mail In 1925, the Patterson Athletic Club, sponsored by Toronto's Patterson Candies, finished third in the Ontario Ladies Track and Field Championship. The Club managed First-place finishes in the discus, the 220-yards, the 120-yard low hurdles, and the long jump, and Second place in the 100-yards, and the javelin. All in all, an impressive showing by the "Pats," rendered the more so by the fact that the Club had but one entrant in the meet - Fanny "Bobbie" Rosenfeld. The easiest way to describe Bobbie Rosenfeld's athleticism is to say that the only sport at which she did not excel was swimming. She was the consummate team player. She dominated every sport she tried, track and field, softball, basketball, lacrosse and, her favourite team sport, hockey. This documentary is the life story of this funny and unusual woman who loved to perform for a large audience. No stage could provide her a bigger audience than the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics: the first year that women were allowed to participate in track and field events. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

All-Time Greats All-Time Greats

FEATURE STORY All-Time Greats Take a look back in our history and you’ll find plenty of outstanding athletes. These particular stars all brought something extra-special to their sports. Chantal Petitclerc (born 1969) Saint-Marc-des-Carrières, Que. When an accident at age 13 left her paraplegic — unable to use her legs — Petitclerc started Wikipedia swimming to keep fit and get stronger. At 17, she discovered wheelchair racing, the sport where CP Wikipedia Images, she would excel. Petitclerc won five gold medals and broke three world records at the 2004 Paralympics in Greece, and repeated that astonishing feat at the 2008 Paralympics in China. Wikipedia In total, she won 21 medals at five Paralympic Games. She still holds the world records in the 200- and 400-metre events. In 2016, she was named to the Canadian Senate. 1212 KAYAK DEC 2017 Kayak_62.indd 12 2017-11-15 10:02 AM Willie O’Ree (born 1935) Fredericton, N.B. It was known as the colour barrier — a sort of unofficial, unwritten agreement among owners of professional sports teams that only white athletes should be allowed to play. (The amazing Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s colour barrier in 1946 when he played a season with the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers' minor league team.) It took more than a decade for the same thing to happen in the NHL. The player was Willie O’Ree, a speedy skater who had played all over New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario before the Boston Bruins put him on the ice in 1958. He retired from the game in the late 1970s. -

Canadianliterature / Littérature Canadienne

Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number "#", Autumn "##$, Sport and the Athletic Body Published by !e University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Larissa Lai (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (%$&$–%$''), W.H. New (%$''–%$$&), Eva-Marie Kröller (%$$&–"##(), Laurie Ricou ("##(–"##') Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität zu Köln Allison Calder University of Manitoba Kristina Fagan University of Saskatchewan Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Helen Gilbert University of London Susan Gingell University of Saskatoon Faye Hammill University of Strathclyde Paul Hjartarson University of Alberta Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Reingard Nischik University of Constance Ian Rae King’s University College Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Sherry Simon Concordia University Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Cynthia Sugars University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Marie Vautier University of Victoria Gillian Whitlock University of Queensland David Williams University of Manitoba -

On This Date Matchless Six Happy Birthday!

THE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2021 On This Date 455 – The Vandals, a Germanic Quote of the Day tribe, entered Rome and plundered the city for two weeks. This led to “How can a guy climb trees, the coinage of vandalism, meaning say ‘Me Tarzan, you Jane,’ “senseless destruction.” and make a million?” 1763 – Ojibwe followers of Chief ~ Johnny Weissmuller , Olympic Pontiac captured the British Fort swimmer and star of six 1930s Michilimackinac by diverting the and 1940s Tarzan movies garrison’s attention with a game of lacrosse and then chasing a ball into the fort. Today, the Happy Birthday! grounds in Michigan In 1928, Jane Bell (1910–1998), at are a major component age 18, was the youngest member of the Mackinac State of the “Matchless Six,” Canada’s Historic Parks. first women’s Olympic track team. 1910 – Charles Stewart Rolls, one of She and teammates Myrtle Cook, the founders of Rolls Royce, became Bobbie Rosenfeld, the first man to fly an airplane across and Ethel Smith the English Channel. He died the next won the gold medal month when the plane he was flying in world record time broke apart in mid-air. in the 4x100m relay at the Amsterdam Olympic Games. Overall, the Matchless Six won four Matchless Six medals at the 1928 Olympic Games. The Matchless Six returned to Bell was also a competitive swimmer, ticker-tape parades in Toronto curler, and golfer. She later became a and Montreal. physical education teacher in Toronto. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) EDNESDAY UNE W , J 2, 2021 Today is Global Running Day. -

A Historical • Ethnographic Account of a Canadian

A Historical • Ethnographic Account Of A Canadian Woman in Sport, 1920 -1938: The Story of Margaret (Bell) Gibson by Katherine M. Laubman B.P.E., The University of Alberta, 1968 A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Master of Physical Education in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (School Of Physical Education and Recreation) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia August 1991 Katherine Laubman, 1991 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date A&Lfjrl, mi DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This study attempted to discover and describe the cultural knowledge and understandings that Margaret (Bell) Gibson derived from her performance as a highly successful athlete in Canadian women's sport during the 1920s - 1930s. A case study approach was used that employed qualitative research strategies. This approach was considered appropriate as prominent issues in women's lives are subtle and context- bound. A series of five informal interviews was conducted with Bell, using an ethnographic approach developed by Spradley (1979). -

“Bobbie” Rosenfeld: a “Modern Woman” of Sport and Journalism in Twentieth-Century Canada

Sport History Review, 2013, 44, 120-143 © 2013 Human Kinetics, Inc. Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld: A “Modern Woman” of Sport and Journalism in Twentieth-Century Canada Christina Burr and Carol A. Reader University of Windsor Jewish-Canadian athlete Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld has been remembered as an exceptional all-around athlete, whose career triumph occurred at the 1928 Olym- pics where she won a gold medal as the lead-off member of the 4 × 100-meter relay team, a silver medal in the disputed 100-meter race, and placed fifth in the 800-meter race. She was also a hard-hitting sports journalist, in an occupation dominated by men, who championed women’s issues at all levels—local, national, and international—through her daily column for the Toronto Globe and Mail from 1937 to 1958; a coach for the women’s track and field team at the 1934 British Empire Games; and a critic of sport policy, particularly amateur athletics. In 1950 she was named Canada’s woman athlete of the half-century, narrowly edging out figure skater Barbara Ann Scott. The only Jewish athlete ever to win a gold medal in track and field, she was inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in Israel in 1981. The accolades for Rosenfeld continued to mount. In 1991 the city of Toronto established the Bobbie Rosenfeld Park situated between the Sky Dome and the CN Tower. On 9 June 1996, the Canada Post Corporation paid tribute to the 100th anniversary of the Modern Olympic Games by issuing five stamps honoring Canadian Olympians who distinguished themselves at previous -

Second Story Fall 2018

Second Story Press FALL 2018 FREE ESL TEACHER GUIDES: Bring diversity, social justice, and chil- dren’s empowerment into the classroom with our ESL teacher resource guides. These short, adaptable guides provide pre-reading, listening and speaking, and writing and comprehension activities for ESL/ELL students. I Am Not a Number (p.10) The Pain Eater (p.11) « Silver Birch Express Award Finalist, 2018 « Snow Willow Award Finalist, 2018 « Red Cedar Award for Information Book Finalist, « In the Margins Book Award 2017 Top Ten List, 2018 « Hackmatack Award Finalist, « Sequoyah Book Awards, 2017-18 High School List, 2019 « Diamond Willow Award Finalist, 2018 « AWARD HIGHLIGHTS AWARD Rocky Mountain Book Award Download the guides for FREE at Finalist, 2017 www.secondstorypress.ca « Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award Finalist, 2017 « Information Book Award Finalist, 2017 To Look a Nazi in the Saying Goodbye to Stolen Words (p.10) The Mask that Sang « Elizabeth Mrazik Cleaver Canadian (p.10) Eye (p.16) London (p.11) « Sydney Taylor Book « Sheila A. Egoff Children’s Picture Book Award Finalist, 2017 « Burt Award for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Award for Older Literature Prize Finalist, « OLA Best Bets, 2018 YA Literature, Honour Readers, Silver Medal, 2018 Book 2017 2018 Cover illustration © Naomi M. Moyer Printed in Canada Second Story Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Follow us on Twitter: @_secondstory Ontario Media Development Corporation. -

7Th Grade Biographies/Autobiographies Saturday, November 26, 2011 7:13:16 AM Emmaus Lutheran School Sorted By: Title

AR BookGuide™ Page 1 of 224 7th Grade Biographies/Autobiographies Saturday, November 26, 2011 7:13:16 AM Emmaus Lutheran School Sorted by: Title Quiz Word Title Author Number Lang IL BL Pts F/NF Count Book RP RV LS VP Description The $64 Tomato Alexander, William 113831 EN UG 7.5 12.0 NF 65863 N N - - - Bill Alexander recounts the challenges he faced while trying to cultivate his own vegetable garden and offers a cost- benefit analysis of his efforts, determining that it cost him $64 to grow each of his beloved tomatoes. 10 Explorers Who Changed the Gifford, Clive 133277 EN MG 7.7 2.0 NF 13150 N N - - - This book presents the stories of ten World explorers whose discoveries influenced the course of world events and shows how these pioneers were linked even though their adventures occurred at different points in history. The 10 Greatest Hoop Heroes Hurley, Trish 122557 EN MG 7.0 2.0 NF 9890 N N - - - This book gives brief biographies of ten of the greatest basketball players to have ever hit the hard court. The 10 Greatest Spies Mitchell, Geneviève 122558 EN MG 7.3 2.0 NF 8990 N N - - - This book discusses the dark and dangerous world of history's greatest spies. 10 Kings & Queens Who Changed Gifford, Clive 132512 EN MG 7.8 2.0 NF 12064 N N - - - This book profiles the lives of ten the World significant kings and queens throughout history and features information on Hatshepsut, Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Henry VIII, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent, Elizabeth I, and Catherine the Great.