A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobbie Rosenfeld: the Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin

2005 GOLDEN OAK BOOK CLUB™ SELECTIONS Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin BOOK SUMMARY: Not so long ago, girls and women were discour- aged from playing games that were competitive and rough. Well into the 1950s, there was gen- der discrimination in sports. Girls were consid- ered too fragile and sensitive to play hard and to play well. But one woman astonished everyone. In fact, sportswriters and broadcasters in this country agree that Bobbie Rosenfeld may be Canada’s all-round greatest athlete of the twen- tieth century. Bobbie excelled at hockey, bas- ketball, softball, and track and field, and she became one of Canada’s first female Olympic medallists. Just as remarkable as her talent was her extraordinary sense of fair play. She greeted obstacles with courage, hard work, and a sense of humor, and she always put the team ahead of herself. In doing so, Bobbie set an example as a true athletic hero. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY: Like Bobbie Rosenfeld, Anne Dublin came to Canada at a young age. She worked as an elementary school teacher for over 25 years, and taught in Kingston, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Nairobi. During her writing career, Anne has written short stories, articles, poetry, and a novel called Written on the Wind. Anne currently works as a teacher- librarian in Toronto. Ontario Library Association Reading Programs ©2002-2005. Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin Suggestions for Tutors/Instructors 6. Why did sports become more popular with women? Before starting to read the story, read (aloud) the outside 7. -

Ice Hockey Packet # 23

ICE HOCKEY PACKET # 23 INSTRUCTIONS This Learning Packet has two parts: (1) text to read and (2) questions to answer. The text describes a particular sport or physical activity, and relates its history, rules, playing techniques, scoring, notes and news. The Response Forms (questions and puzzles) check your understanding and apprecia- tion of the sport or physical activity. INTRODUCTION Ice hockey is a physically demanding sport that often seems brutal and violent from the spectator’s point of view. In fact, ice hockey is often referred to as a combination of blood, sweat and beauty. The game demands athletes who are in top physical condition and can maintain nonstop motion at high speed. HISTORY OF THE GAME Ice hockey originated in Canada in the 19th cen- tury. The first formal game was played in Kingston, Ontario in 1855. McGill University started playing ice hockey in the 1870s. W. L. Robertson, a student at McGill, wrote the first set of rules for ice hockey. Canada’s Governor General, Lord Stanley of Preston, offered a tro- phy to the winner of the 1893 ice hockey games. This was the origin of the now-famed Stanley Cup. Ice hockey was first played in the U. S. in 1893 at Johns Hopkins and Yale universities, respec- tively. The Boston Bruins was America’s first NHL hockey team. Ice hockey achieved Olym- pic Games status in 1922. Physical Education Learning Packets #23 Ice Hockey Text © 2006 The Advantage Press, Inc. Through the years, ice hockey has spawned numerous trophies, including the following: NHL TROPHIES AND AWARDS Art Ross Trophy: First awarded in 1947, this award goes to the National Hockey League player who leads the league in scoring points at the end of the regular hockey season. -

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

N G P Iiila M's Shortstop in Trouble Niners Pick up QB Renegades

10 - The Prince George Citizen - Friday, June 14, 2002 N u m b e r s G a m e p i i il a WHI LOCAL SCENE NHL Playoffs s p o r t s T O D A Y Canadian Junior Woywitka. Vermilion. Alta , Red Deer (WHL) Westwood Sports Philadelphia 2001 STANLEY CUP FINAL Team Summer Camp Forwards Pterre-Marc Bouchard. To place information in our daily Citizen Pub Senior Baseball Boucherville Q ue. Chicoutimi (QMJHL)2002 CALGARY (CP) — Players invited to the draft eligible. Shawn Collymore Lasalle, Q ue. (1) Detroit Red W ings vs. (3) Carolina Hurricanes sports calendar, or to keep Prince George and Wednesday results Canadian junior hockey team developmentQuebec (QMJHL), New York Rangers 2001. Grays 7 Panage Predators 3 area up to date on results, fax The Citizen camp Aug 10-12 in Halifax (with home town,Nicolas Corbeil Laval Que Sherbrooke WP Adam Walton, IP Derek Knight team affiliation and draft status) Last Night: Detroit 3 Carolina I (QMJHL) Toronto 2001, Owen Fussey. Previous Results: Carolina 3 Detroit 2 (OT) sports departm ent at 562-7453 or e-mail us at: Hr, Kevin Massicotte Goaltenders Barry Brust Weslbank. Winnipeg. Calgary (WHL), Washington 2001, FP Knights 9 Eco-Pute Water Cimmerians 5 Detroit 3 Carolina l Detroit Wins sports@ princegeorgecitizen.com Spokane (WHL), 2002 draft eligible, Jeff Boyd Gordon, Regina. Red Deer (WHL), 2002 WP Geolt Fahlman; Save Jody HamiltonDrouin-Deslauriers Sl-Jean-Richelieu Q ue. Detroit 3 Carolina 2 (OT) Series 4-1 draft eligible. Matt Keith. Aldergrove. Spokane IP Kevin Dowswell Detroit 3 Carolina 0 Chicoutimi (QMJHL) 2002 draft eligible (WHL). -

Passive Participation: the Selling of Spectacle and the Construction of Maple Leaf Gardens, 1931

Sport History Review, 2002, 33, 35-50 PASSIVE PARTICIPATION 35 © 2002 Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Passive Participation: The Selling of Spectacle and the Construction of Maple Leaf Gardens, 1931 Russell Field In 1927, Conn Smythe, a Toronto businessman and hockey enthusi- ast, organized a group to purchase Toronto’s entry in the National Hockey League (NHL). Operating out of the fifteen-year-old Arena Gardens, the St. Patricks (who Smythe renamed Maple Leafs) had for years been only moderately successful both on the ice and at the cashbox. Compounding Smythe’s local and competitive circumstances was the changing nature of the NHL in the mid 1920s. Beginning in 1924, the Canadian-based NHL clubs reaped the short-term benefits of expansion fees paid by the new American teams, but the latter’s greater capital resources and newer, larger playing facilities soon shifted the economic balance of power within the “cartel” south of the border.1 As Thompson and Seager note of this period: “Canadian hockey was revolutionized by American money.”2· Despite the Maple Leafs’ bleak economic circumstances, Smythe had big dreams for himself and his hockey team. In attempting to realize his vision, he built Canada’s best-known sports facility, Maple Leaf Gardens, managed the Maple Leafs into one of the NHL’s wealthiest clubs, and assumed majority ownership of the team. The economic and cultural impact of the major NHL-inspired arena projects of the 1920s and early 1930s—the Montreal Forum, New York’s Madison Square Garden, Boston Garden, Chicago Stadium, the Detroit Olympia, as well as Maple Leaf Gardens—has received little attention among scholarly contributions to the study of sport.3 However, there has been greater interest in the politics of arena and stadium construction, and work by scholars such as John Bale and Karl Raitz has helped to define and explore the notion of arenas and stadiums as sport spaces.4 Adding a fur- ther temporal context to these issues then, allows changes over time to be meaningfully explored. -

Boston Guide

what to do U wherewher e to go U what to see July 13–26, 2009 Boston FOR KIDS INCLUDING: New England Aquarium Boston Children’s Museum Museum of Science NEW WEB bostonguide.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! oyster perpetual gmt-master ii The moon landing 40th anniversary. See how it Media Sponsors: OFFICIALROLEXJEWELER JFK ROLEX OYSTER PERPETUAL AND GMT-MASTER II ARE TRADEMARKS. began at the JFK Presidential Library and Museum. Columbia Point, Boston. jfklibrary.org StunningCollection of Murano Glass N_Xc\ NXkZ_ E\n <e^cXe[ 8hlXi`ld J`dfej @D8O K_\Xki\ Pfli e\ok Furnishings, Murano Glass, Sculptures, Paintings, X[m\ekli\ Tuscan Leather, Chess Sets, Capodimonte Porcelain Central Wharf, Boston, MA www.neaq.org | 617-973-5206 H:K:CIN C>C: C:L7JGN HIG::I s 7DHIDC B6HH68=JH:IIH XnX`kj telephone s LLL <6AA:G>6;ADG:CI>6 8DB DAVID YURMAN JOHN HARDY MIKIMOTO PATEK PHILIPPE STEUBEN PANERAI TOBY POMEROY CARTIER IPPOLITA ALEX SEPKUS BUCCELLAITI BAUME & MERCIER HERMES MIKIMOTO contents l Jew icia e ff le O r COVER STORY 14 Boston for Kids The Hub’s top spots for the younger set DEPARTMENTS 10 hubbub Sand Sculpting Festival and great museum deals 18 calendar of events 20 exploring boston 20 SIGHTSEEING 30 FREEDOM TRAIL 32 NEIGHBORHOODS 47 MAPS 54 around the hub 54 CURRENT EVENTS 62 ON EXHIBIT 67 SHOPPING 73 NIGHTLIFE 76 DINING on the cover: JUMPING FOR JOY: Kelly and Patrick of Model Kelly and Patrick enjoy the Club Inc. take a break in interactive dance floor in the front of a colorful display Boston Children’s Museum’s during their day of fun at the Kid Power exhibit area. -

Download This Page As A

Historica Canada Education Portal Bobbie Rosenfeld Overview This lesson is based on viewing the Bobbie Rosenfeld biography from The Canadians series. Rosenfeld won several medals at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, the first time women were permitted to compete in track and field events. The lesson explores Rosenfeld's career and the level of acceptance for female athletes in the 1920's. Aims In a variety of creative activities, students will assess and evaluate Rosenfeld's accomplishments while considering both the historic and comtemporary role of women in competitive sport. Background "Miss Rosenfeld, who never had a coach, was that rarity, a natural athlete." -Globe and Mail In 1925, the Patterson Athletic Club, sponsored by Toronto's Patterson Candies, finished third in the Ontario Ladies Track and Field Championship. The Club managed First-place finishes in the discus, the 220-yards, the 120-yard low hurdles, and the long jump, and Second place in the 100-yards, and the javelin. All in all, an impressive showing by the "Pats," rendered the more so by the fact that the Club had but one entrant in the meet - Fanny "Bobbie" Rosenfeld. The easiest way to describe Bobbie Rosenfeld's athleticism is to say that the only sport at which she did not excel was swimming. She was the consummate team player. She dominated every sport she tried, track and field, softball, basketball, lacrosse and, her favourite team sport, hockey. This documentary is the life story of this funny and unusual woman who loved to perform for a large audience. No stage could provide her a bigger audience than the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics: the first year that women were allowed to participate in track and field events. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX ’67: The Maple Leafs, Their Sensational Victory, and the End of an Empire (Cox, Stellick), 220 A Anaheim Duck Pond, 245 Abrecht, Cliff, 10 Anaheim Ducks, 30, 123, 191, Acton, Keith, 57 238, 245 Adams Division, 6, 184 Anderson, Dean, 10, 11 agent, free, 12, 16 17, 74, 75, 86, Anderson, Glenn, 63, 86, 90, 91, 87, 223 203, 204 agent (players’), role of, 112 Anderson, John, 48, 49, 50 Air Canada Centre (Toronto), Anderson, Shawn, 62, 63 17, 76 Anderson, Sparky, 11 Alberta Oilers, 225 Andreychuk, Dave, 86, 126 Allen, Keith,COPYRIGHTED 111 Antropov, MATERIAL Nik, 64 Allison, Mike, 166, 167 Anzalone, Frank, 78, 79 All-Star Game (NHL), 13, 14, 36 Arbour, Al, 108, 180, 217 Amateur Draft, 99 Archibald, Dave, 4 American Hockey League (AHL), 10, Armstrong, George, 49, 50, 51, 21, 33, 67, 77–79, 99, 118, 125, 134, 158, 161, 214, 215 155–56, 164, 166, 216–17, 242, Art Ross Trophy, 212 249, 262, 264 Ashley, John, 215 Amonte, Tony, 202 Astrom, Hardy, 135 BBINDEX.inddINDEX.indd 226565 112/08/112/08/11 112:352:35 AAMM 266 | Index Atlanta Flames, 163, 238. See also Boston Bruins, 6–9, 49, 54–55, Calgary Flames 60–61, 73, 74, 95, 130–32, 189, Aubin, Normand, 155, 156 192–93, 202, 206, 208–13, 216, Aubut, Marcel, 203 223, 247, 248–49 Boston Globe, 131 B Boston Herald-American, 131 Badali, Gus, 122 Boston Red Sox, 89, 239 Bailey, Garnet “Ace”, 252, 253 Bouchard, Pierre, 219, 221, 111 Ballard, Bill, 171, 173 Boucher, Brian, 74 Ballard, Harold, 4, 5, 17, 18, 49, Boudrias, Andre, 125 50–52, 103, 116, 119, 121, Bourque, Raymond, 7–10, 128, 134, 138–42, 145, 191, 196–97, 189, 202 216, 224, 228–29, 231–35, Bowen, Joe, 83, 89, 241, 242, 243 259, 261 Bowlen, Pat, 72 and frugality, 158–60 Bowman, Scotty, 119, 180, 181, 182, Ballard, Yolanda. -

1934 SC Playoff Summaries

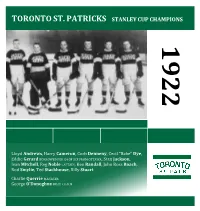

TORONTO ST. PATRICKS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 192 2 Lloyd Andrews, Harry Cameron, Corb Denneny, Cecil “Babe” Dye, Eddie Gerard BORROWED FOR G4 OF SCF FROM OTTAWA, Stan Jackson, Ivan Mitchell, Reg Noble CAPTAIN, Ken Randall, John Ross Roach, Rod Smylie, Ted Stackhouse, Billy Stuart Charlie Querrie MANAGER George O’Donoghue HEAD COACH 1922 NHL FINAL OTTAWA SENATORS 30 v. TORONTO ST. PATRICKS 27 GM TOMMY GORMAN, HC PETE GREEN v. GM CHARLIE QUERRIE, HC GEORGE O’DONOGHUE ST. PATRICKS WIN SERIES 5 GOALS TO 4 Saturday, March 11 Monday, March 13 OTTAWA 4 @ TORONTO 5 TORONTO 0 @ OTTAWA 0 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. TORONTO, Ken Randall 0:30 NO SCORING 2. TORONTO, Billy Stuart 2:05 3. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:05 SECOND PERIOD 4. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 7:05 NO SCORING 5. OTTAWA, Cy Denneny 11:00 THIRD PERIOD SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING 6. TORONTO, Babe Dye 3:50 7. OTTAWA, Frank Nighbor 6:20 Game Penalties — Cameron T 3, Corb Denneny T, Clancy O, Gerard O, Noble T, F. Boucher O 2, Smylie T 8. TORONTO, Babe Dye 6:50 GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach THIRD PERIOD 9. TORONTO, Corb Denneny 15:00 GWG Officials: Cooper Smeaton At The Arena, Ottawa Game Penalties — Broadbent O 3, Noble T 3, Randall T 2, Dye T, Nighbor O, Cameron T, Cy Denneny O, Gerard O GOALTENDERS — SENATORS, Clint Benedict; ST. PATRICKS, John Ross Roach Official: Cooper Smeaton 8 000 at Arena Gardens © Steve Lansky 2014 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. -

Induction Spotlight Tsn/Rds Broadcast Zone Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL INDUCTION SPOTLIGHT TSN/RDS BROADCAST ZONE RECENT ACQUISITIONS SPRING 2015 CORPORATE MATTERS LETTER FROM THE INDUCTION 2015 • The annual elections meeting of the Selection Committee VICe-CHAIR will be held in Toronto on June 28 & 29, 2015 (with the announcement of the 2015 inductees on June 29th). Dear Teammates: • The Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Celebration will be held on Monday, November 9, 2015. Not long after another successful Graig Abel/HHOF Induction Celebration last November, the closely knit hockey community mourned the loss of two of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the game’s most accomplished and respected individuals in Pat • Scotty Bowman, David Branch, Brian Burke, Marc de Foy, Mike Gartner and Anders Quinn and Jean Beliveau. I have been privileged to get to know Hedberg were re-appointed each to a further term on the Selection Committee for the and work with these distinguished gentlemen throughout my 2015, 2016 and 2017 selection proceedings. life in hockey and like many others I was particularly heartened • The general voting Members ratified new By-law Nos. 25 and 26 which, among other by the outstanding tributes that spoke volumes to their impact amendments, provide for improved voting procedures applicable to all categories of on our great sport. Honoured Membership (visit HHOF.com for full transcripts). Although Chair of the Board for little more than a year, Pat left his mark on the Hockey Hall of Fame, overseeing the recruitment BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nominated by: of new members to the Selection Committee, initiating the Lanny McDonald, Chair (1) Corporate Governance Committee first comprehensive selection process review which led to Jim Gregory, Vice-Chair National Hockey League several by-law amendments, and establishing new and renewed Murray Costello Corporate Governance Committee partnerships. -

A Last Talk with Leslie Mcfarlane

A Last Talk with Leslie McFarlane DA VID PALMER L eslie McFarlane, one of the world's most popular children's authors and a prolific contributor to Canadian popular culture, died on September 6th, 1977, in Whitby, Ontario. Born at Carleton Place, Ontario, in 1902, he worked as a reporter for several newspapers in Ontario and Massachusetts, and from the twenties to the forties contributed hundreds of stories and serials to the "better pulps" and "sn~ooth-paper magazines" (as Maclean's explained in 1940) in Canada, the U.S.A. and Great Britain. In this period he also published two novels, and under various pseudonyms wrote numerous children's adventure books for the Stratemeyer Syndicate of New Jersey (home of the Bobbsey Twins), including the first Hardy Boys books. In the late thirties and forties he wrote dozens of radio plays, and in 1944, after two years with the Department of Munitions and Supply, he was invited by John Grierson to join the National Film Board. During the next fourteen years he wrote, produced or directed (often all three) twenty- eight documentary fbs, winning several awards and an Oscar nomination. In 1958 he became head of the television drama script department at the CBC and wrote many television plays for that and other networks. He continued to produce occasional books (and revisions of earlier works) for children, and some of these later writings are reviewed elsewhere in this issue of CCL. Ironically, in view of this enormous output, McFarlane is probably best known now as the original Franklin W. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award .................................................................................................