A Last Talk with Leslie Mcfarlane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

While the Clock Ticked Ebook

WHILE THE CLOCK TICKED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Franklin W. Dixon | 180 pages | 01 Apr 2002 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448089119 | English | New York, United States While the Clock Ticked PDF Book D loves his secret room, er, he did This book takes place in Bayport only. Open Preview See a Problem? Nov 13, Jon rated it it was amazing. I didn't really make a connection with the book, because I have never solved a real life detective mystery. See all 14 brand new listings. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. See 2 questions about While the Clock Ticked…. The book was very believable because it all made sense, I wasn't getting confused like what how did that happen. Kids' Club Eligible. Friend Reviews. What Happened at Midnight. View all 8 comments. The Hardy Boys let him inside to hear his story but he won't talk to them. A mysterious stranger apparently steals some of Mr. Frank and Joe are bound and gagged, along with an inventor named Amos Wandy, with a time bomb set to go off at 3 a. We've got you covered with the buzziest new releases of the day. Mystery book are interesting because there can be a huge twist in the book that can change everything. Surprisingly they are rescued by Mr. We get a nice comedic sequence featuring a starving Chet Millions of young readers have teamed up with the Hardy Boys, helping them in their quest to bring cri Frank and Joe solve the mystery of the secret locked room in the spooky Dalrymple Mansion. -

Download Download

69 Books in Review / Comptes rendus continued in the next chapter, which looks at the federal government's imposition of print culture on Aboriginal people in the first 25 years of the twentieth century. Yet, Edwards shows that in many cases the Department of Indian Affairs only began using books and libraries as assimilative agents after Aboriginal people, such as Charles A. Cooke, requested them. The fourth chapter examines community development, philanthropy, and educational neglect from 193o to 1960, concluding with a description of the efforts of Angus McGill Mowat, former head of Public Libraries Branch of the Ontario Department of Education, to establish a large public library at Moose Factory for the Cree and Ojibwa living there. Paper Talk· provides a cohesive and richly detailed narrative that outlines general patterns among Aboriginal people combined with illustrations of specific examples in local contexts. Edwards balances solid primary research with careful integration of published works in the field. The book will be of interest to scholars of both Aboriginal peoples and the history of the book. CAROLYN PODRUCHNY YorkEUniversity Richard A. Davies. Inventing Sam SlickE: A Biography of Thomas Chandler Haliburton. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, zooy. 316 pp.; $60.00. ISBN: 08020soox8. Richard Davies admits that "a good portion" (xi) of his life was consumed by this long-awaited biography of the Nova Scotia writer, Thomas Chandler Haliburton. In fact, Davies has devoted his scholarly career to Haliburton studies. He is editor of the essay collection, On Thomas Chandler Haliburton (I979); The Letters of Thomas Chandler Haliburton (r988); and the proceedings of the 1996 Thomas Raddall Symposium, published as The Haliburton Bi-centenary Chaplet (1997). -

A Visit to Whitby, Ontario Last Home of Leslie Mcfarlane by David Baumann 571 Words

A Visit to Whitby, Ontario Last Home of Leslie McFarlane by David Baumann 571 words Although I live in southern California, I spent this past week in Ontario, Canada for a conference in Windsor. Having the opportunity, I went two days early to see the countryside. On Wednesday, I suddenly realized that I was about twenty miles from Whitby, a relatively small town east of Toronto, and remembered that this was where Leslie McFarlane spent his last years and where he died in early September 1977. I decided to go there and discover what I could. First I called the general information number for Whitby to learn where he was buried. The helpful person on the end of the line referred me to an old-timer who runs the archives, but he was on vacation. A second referral sent me to the public library. Another helpful person looked up the records and told me that McFarlane was buried from the Town Funeral Home. When I pulled into Whitby, it was easy to find the funeral home where two gentlemen went out of their way to pull up their old, pre-computer records. A thick folder with the name LESLIE McFARLANE came out of a stack of others from 1977. Inside were not only the records of the arrangements but also about ten single-spaced typewritten pages that were a summary of an interview with McFarlane that had taken place shortly before he died. It contains a huge amount of information about the Hardy Boys. It was not indicated who had done the interview or for what purpose. -

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09

Accelerated Reader Book List 08-09 Test Number Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3.0 0.5 107287EN 15 Minutes Steve Young 4.0 4.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.2 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4.0 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.7 2.0 71428EN 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda/Rosner 4.3 2.0 81642EN Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6.0 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 76357EN The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6.0 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4.0 1.0 117747EN Abracadabra! Magic with Mouse an Wong Herbert Yee 2.6 0.5 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.5 3.0 17651EN The Absent Author Ron Roy 3.4 1.0 10151EN Acorn to Oak Tree Oliver S. Owen 2.9 0.5 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 7201EN Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg 1.7 0.5 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4.0 76892EN Actual Size Steve Jenkins 2.8 0.5 86533EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Michael Winerip 5.4 9.0 118142EN Adam Canfield, -

Induction Spotlight Tsn/Rds Broadcast Zone Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL INDUCTION SPOTLIGHT TSN/RDS BROADCAST ZONE RECENT ACQUISITIONS SPRING 2015 CORPORATE MATTERS LETTER FROM THE INDUCTION 2015 • The annual elections meeting of the Selection Committee VICe-CHAIR will be held in Toronto on June 28 & 29, 2015 (with the announcement of the 2015 inductees on June 29th). Dear Teammates: • The Hockey Hall of Fame Induction Celebration will be held on Monday, November 9, 2015. Not long after another successful Graig Abel/HHOF Induction Celebration last November, the closely knit hockey community mourned the loss of two of ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the game’s most accomplished and respected individuals in Pat • Scotty Bowman, David Branch, Brian Burke, Marc de Foy, Mike Gartner and Anders Quinn and Jean Beliveau. I have been privileged to get to know Hedberg were re-appointed each to a further term on the Selection Committee for the and work with these distinguished gentlemen throughout my 2015, 2016 and 2017 selection proceedings. life in hockey and like many others I was particularly heartened • The general voting Members ratified new By-law Nos. 25 and 26 which, among other by the outstanding tributes that spoke volumes to their impact amendments, provide for improved voting procedures applicable to all categories of on our great sport. Honoured Membership (visit HHOF.com for full transcripts). Although Chair of the Board for little more than a year, Pat left his mark on the Hockey Hall of Fame, overseeing the recruitment BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nominated by: of new members to the Selection Committee, initiating the Lanny McDonald, Chair (1) Corporate Governance Committee first comprehensive selection process review which led to Jim Gregory, Vice-Chair National Hockey League several by-law amendments, and establishing new and renewed Murray Costello Corporate Governance Committee partnerships. -

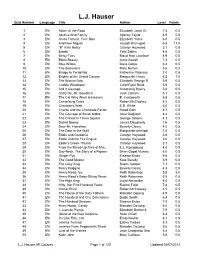

AR Quizzes for L.J. Hauser

L.J. Hauser Quiz Number Language Title Author Level Points 1 EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 7.4 0.5 2 EN All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor 4.9 0.5 3 EN Amos Fortune, Free Man Elizabeth Yates 6.0 0.5 4 EN And Now Miguel Joseph Krumgold 6.8 11.0 5 EN "B" is for Betsy Carolyn Haywood 3.1 0.5 6 EN Bambi Felix Salten 4.6 0.5 7 EN Betsy-Tacy Maud Hart Lovelace 4.9 0.5 8 EN Black Beauty Anna Sewell 7.3 0.5 9 EN Blue Willow Doris Gates 6.4 0.5 10 EN The Borrowers Mary Norton 5.6 0.5 11 EN Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 7.0 0.5 12 EN Brighty of the Grand Canyon Marguerite Henry 6.2 7.0 13 EN The Bronze Bow Elizabeth George S 5.9 0.5 14 EN Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink 5.6 0.5 15 EN Call It Courage Armstrong Sperry 5.0 0.5 16 EN Carry On, Mr. Bowditch Jean Latham 5.1 0.5 17 EN The Cat Who Went to Heaven E. Coatsworth 5.8 0.5 18 EN Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey 5.2 0.5 19 EN Charlotte's Web E.B. White 6.0 0.5 20 EN Charlie and the Chocolate Factor Roald Dahl 6.7 0.5 21 EN The Courage of Sarah Noble Alice Dalgliesh 4.2 0.5 22 EN The Cricket in Times Square George Selden 4.3 0.5 23 EN Daniel Boone James Daugherty 7.6 0.5 24 EN Dear Mr. -

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M

Series Books Through the Lens of History by David M. Baumann This article first appeared in The Mystery and Adventure Series Review #43, summer 2010 Books As Time Machines It was more than half a century ago that I learned how to type. My parents had a Smith-Corona typewriter—manual, of course—that I used to write letters to my cousins. A few years later I took a “typing class” in junior high. Students were encouraged to practice “touch typing” and to aim for a high number of “words per minute”. There were distinctive sounds associated with typing that I can still hear in my memory. I remember the firm and rapid tap of the keys, much more “solid” than the soft burr of computer “keyboarding”. A tiny bell rang to warn me that the end of the line was coming; I would finish the word or insert a hyphen, and then move the platen from left to right with a quick whirring ratchet of motion. Frequently there was the sound of a sheet of paper being pulled out of the machine, either with a rip of frustration accompanied by an impatient crumple and toss, or a careful tug followed by setting the completed page aside; then another sheet was inserted with the roll of the platen until the paper was deftly positioned. Now and then I had to replace a spool of inked ribbon and clean the keys with an old toothbrush. Musing on these nearly vanished sounds, I put myself in the place of the writers of our series books, nearly all of whom surely wrote with typewriters. -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE YELLOW FEATHER MYSTERY By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 33 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the 1953 original text. In the 1953 original, the Hardy Boys go to the Woodson Academy to solve the mystery of a missing will. The 1971 revision is slightly altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of Wildcat -

THE SECRET PANEL by FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys Series

THE SECRET PANEL By FRANKLIN W. DIXON No. 25 in the Hardy Boys series. This is the original 1946 text. In the 1946 original, the Hardy Boys solve a kidnapping mystery at the weird Mead House, which lacks both door knobs and hinges. The 1969 revision is altered. The Hardy Boys series by Franklin W. Dixon, the first 58 titles. The first year is the original year. The second is the year it was revised. 01 The Tower Treasure 1927, 1959 02 The House on the Cliff 1927, 1959 03 The Secret of the Old Mill 1927, 1962 04 The Missing Chums 1927, 1962 05 Hunting for Hidden Gold 1928, 1963 06 The Shore Road Mystery 1928, 1964 07 The Secret of the Caves 1929, 1965 08 The Mystery of Cabin Island 1929, 1966 09 The Great Airport Mystery 1930, 1965 10 What Happened at Midnight 1931, 1967 11 While the Clock Ticked 1932, 1962 12 Footprints Under the Window 1933, 1962 13 The Mark on the Door 1934, 1967 14 The Hidden Harbor Mystery 1935, 1961 15 The Sinister Sign Post 1936, 1968 16 A Figure in Hiding 1937, 1965 17 The Secret Warning 1938, 1966 18 The Twisted Claw 1939, 1964 19 The Disappearing Floor 1940, 1964 20 The Mystery of the Flying Express 1941, 1968 21 The Clue of the Broken Blade 1942, 1969 22 The Flickering Torch Mystery 1943, 171 23 The Melted Coins 1944, 1970 24 The Short Wave Mystery 1945, 1966 25 The Secret Panel 1946, 1969 26 The Phantom Freighter 1947, 1970 27 The Secret of Skull Mountain 1948, 1966 28 The Sign of the Crooked Arrow 1949, 1970 29 The Secret of the Lost Tunnel 1950, 1968 30 The Wailing Siren Mystery 1951, 1968 31 The Secret of -

Robin Hood in the Arctic

Robin Hood in the Arctic DA VID PALMER The Snow Hawlc, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1976. 127 pp. $1.50 paper. The Mystery of Spider Lake, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1975. 128 pp. $1 .SO paper. Agent of the Falcon, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1975. 122 pp. $1.50 paper. Breakaway, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1976. 127 pp. $1.50 paper. Squeeze Play, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1975. 128 pp. $1.50 paper.. The Dynamite Flynrzs, Leslie McFarlane. Methuen, 1975. 126 pp. $1.50 paper. The Last of the Great Picnics, Leslie McFarlane. Illustrated by Lewis Parker. McClelland and Stewart, 1974.99 pp. $2.79 paper. A Kid in Haileybtliy, Leslie McFarlane. Cobalt, Ontario: Highway Book Shop $2.50 paper. he first six of these books, published in the Metl~uenClleclunate series, contain adaptations of magazine stories published by Leslie McFarlane in the twenties and thirties. Two of the boolts contain a single narrative, whde the rest are collections of stories. All are stories cither of northern adventure or of hockey, set in a world that has since considerably changed: a far north of trappers and dog-sleds, prospectors and crude mining towns, of law and order tenuously maintained against violence and skul- duggery; a hockey scene without big money or television, physically raw, and pervaded by desperate local loyalties. But these remain classic examples of tales that are both highly interesting to pre-lugh school clddren and yet easy going for most reluctant readers. Adventure stories of any kind tend to be set in worlds of our collec- tive imagination rather than in those to which we have more direct access.