Politics of Exclusion: an Analysis of the Intersections of Marginalized Identities and the Olympic Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobbie Rosenfeld: the Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin

2005 GOLDEN OAK BOOK CLUB™ SELECTIONS Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin BOOK SUMMARY: Not so long ago, girls and women were discour- aged from playing games that were competitive and rough. Well into the 1950s, there was gen- der discrimination in sports. Girls were consid- ered too fragile and sensitive to play hard and to play well. But one woman astonished everyone. In fact, sportswriters and broadcasters in this country agree that Bobbie Rosenfeld may be Canada’s all-round greatest athlete of the twen- tieth century. Bobbie excelled at hockey, bas- ketball, softball, and track and field, and she became one of Canada’s first female Olympic medallists. Just as remarkable as her talent was her extraordinary sense of fair play. She greeted obstacles with courage, hard work, and a sense of humor, and she always put the team ahead of herself. In doing so, Bobbie set an example as a true athletic hero. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY: Like Bobbie Rosenfeld, Anne Dublin came to Canada at a young age. She worked as an elementary school teacher for over 25 years, and taught in Kingston, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Nairobi. During her writing career, Anne has written short stories, articles, poetry, and a novel called Written on the Wind. Anne currently works as a teacher- librarian in Toronto. Ontario Library Association Reading Programs ©2002-2005. Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything by Anne Dublin Suggestions for Tutors/Instructors 6. Why did sports become more popular with women? Before starting to read the story, read (aloud) the outside 7. -

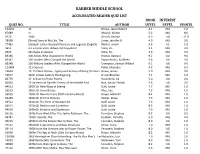

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Download This Page As A

Historica Canada Education Portal Bobbie Rosenfeld Overview This lesson is based on viewing the Bobbie Rosenfeld biography from The Canadians series. Rosenfeld won several medals at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, the first time women were permitted to compete in track and field events. The lesson explores Rosenfeld's career and the level of acceptance for female athletes in the 1920's. Aims In a variety of creative activities, students will assess and evaluate Rosenfeld's accomplishments while considering both the historic and comtemporary role of women in competitive sport. Background "Miss Rosenfeld, who never had a coach, was that rarity, a natural athlete." -Globe and Mail In 1925, the Patterson Athletic Club, sponsored by Toronto's Patterson Candies, finished third in the Ontario Ladies Track and Field Championship. The Club managed First-place finishes in the discus, the 220-yards, the 120-yard low hurdles, and the long jump, and Second place in the 100-yards, and the javelin. All in all, an impressive showing by the "Pats," rendered the more so by the fact that the Club had but one entrant in the meet - Fanny "Bobbie" Rosenfeld. The easiest way to describe Bobbie Rosenfeld's athleticism is to say that the only sport at which she did not excel was swimming. She was the consummate team player. She dominated every sport she tried, track and field, softball, basketball, lacrosse and, her favourite team sport, hockey. This documentary is the life story of this funny and unusual woman who loved to perform for a large audience. No stage could provide her a bigger audience than the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics: the first year that women were allowed to participate in track and field events. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

All-Time Greats All-Time Greats

FEATURE STORY All-Time Greats Take a look back in our history and you’ll find plenty of outstanding athletes. These particular stars all brought something extra-special to their sports. Chantal Petitclerc (born 1969) Saint-Marc-des-Carrières, Que. When an accident at age 13 left her paraplegic — unable to use her legs — Petitclerc started Wikipedia swimming to keep fit and get stronger. At 17, she discovered wheelchair racing, the sport where CP Wikipedia Images, she would excel. Petitclerc won five gold medals and broke three world records at the 2004 Paralympics in Greece, and repeated that astonishing feat at the 2008 Paralympics in China. Wikipedia In total, she won 21 medals at five Paralympic Games. She still holds the world records in the 200- and 400-metre events. In 2016, she was named to the Canadian Senate. 1212 KAYAK DEC 2017 Kayak_62.indd 12 2017-11-15 10:02 AM Willie O’Ree (born 1935) Fredericton, N.B. It was known as the colour barrier — a sort of unofficial, unwritten agreement among owners of professional sports teams that only white athletes should be allowed to play. (The amazing Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s colour barrier in 1946 when he played a season with the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers' minor league team.) It took more than a decade for the same thing to happen in the NHL. The player was Willie O’Ree, a speedy skater who had played all over New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario before the Boston Bruins put him on the ice in 1958. He retired from the game in the late 1970s. -

Canadianliterature / Littérature Canadienne

Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number "#", Autumn "##$, Sport and the Athletic Body Published by !e University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Larissa Lai (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (%$&$–%$''), W.H. New (%$''–%$$&), Eva-Marie Kröller (%$$&–"##(), Laurie Ricou ("##(–"##') Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität zu Köln Allison Calder University of Manitoba Kristina Fagan University of Saskatchewan Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Helen Gilbert University of London Susan Gingell University of Saskatoon Faye Hammill University of Strathclyde Paul Hjartarson University of Alberta Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Reingard Nischik University of Constance Ian Rae King’s University College Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Sherry Simon Concordia University Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Cynthia Sugars University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Marie Vautier University of Victoria Gillian Whitlock University of Queensland David Williams University of Manitoba -

BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera UOMINI 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA), Andre De Grasse (CAN) 2012 Usain Bolt (JAM), Yohan Blake (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA) 2008 Usain Bolt (JAM), Richard Thompson (TRI), Walter Dix (USA) 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA), Francis Obikwelu (POR), Maurice Greene (USA) 2000 Maurice Greene (USA), Ato Boldon (TRI), Obadele Thompson (BAR) 1996 Donovan Bailey (CAN), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Ato Boldon (TRI) 1992 Linford Christie (GBR), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Dennis Mitchell (USA) 1988 Carl Lewis (USA), Linford Christie (GBR), Calvin Smith (USA) 1984 Carl Lewis (USA), Sam Graddy (USA), Ben Johnson (CAN) 1980 Allan Wells (GBR), Silvio Leonard (CUB), Petar Petrov (BUL) 1976 Hasely Crawford (TRI), Don Quarrie (JAM), Valery Borzov (URS) 1972 Valery Borzov (URS), Robert Taylor (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM) 1968 James Hines (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM), Charles Greene (USA) 1964 Bob Hayes (USA), Enrique Figuerola (CUB), Harry Jeromé (CAN) 1960 Armin Hary (GER), Dave Sime (USA), Peter Radford (GBR) 1956 Bobby-Joe Morrow (USA), Thane Baker (USA), Hector Hogan (AUS) 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA), Herb McKenley (JAM), Emmanuel McDonald Bailey (GBR) 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA), Norwood Ewell (USA), Lloyd LaBeach (PAN) 1936 Jesse Owens (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Martinus Osendarp (OLA) 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Arthur Jonath (GER) 1928 Percy Williams (CAN), Jack London (GBR), Georg Lammers (GER) 1924 Harold Abrahams (GBR), Jackson Scholz (USA), Arthur -

On This Date Matchless Six Happy Birthday!

THE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2021 On This Date 455 – The Vandals, a Germanic Quote of the Day tribe, entered Rome and plundered the city for two weeks. This led to “How can a guy climb trees, the coinage of vandalism, meaning say ‘Me Tarzan, you Jane,’ “senseless destruction.” and make a million?” 1763 – Ojibwe followers of Chief ~ Johnny Weissmuller , Olympic Pontiac captured the British Fort swimmer and star of six 1930s Michilimackinac by diverting the and 1940s Tarzan movies garrison’s attention with a game of lacrosse and then chasing a ball into the fort. Today, the Happy Birthday! grounds in Michigan In 1928, Jane Bell (1910–1998), at are a major component age 18, was the youngest member of the Mackinac State of the “Matchless Six,” Canada’s Historic Parks. first women’s Olympic track team. 1910 – Charles Stewart Rolls, one of She and teammates Myrtle Cook, the founders of Rolls Royce, became Bobbie Rosenfeld, the first man to fly an airplane across and Ethel Smith the English Channel. He died the next won the gold medal month when the plane he was flying in world record time broke apart in mid-air. in the 4x100m relay at the Amsterdam Olympic Games. Overall, the Matchless Six won four Matchless Six medals at the 1928 Olympic Games. The Matchless Six returned to Bell was also a competitive swimmer, ticker-tape parades in Toronto curler, and golfer. She later became a and Montreal. physical education teacher in Toronto. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) EDNESDAY UNE W , J 2, 2021 Today is Global Running Day. -

1 Sample Outline with Notecards I. Introduction A. Attention Grabber Title

1 Sample Outline with Notecards This outline includes all the notecards to show you how each notecard is like a puzzle piece of your paper. Notice that tags and page/paragraph number are included on every notecard. You MUST have a paraphrase on each card; direct quotations are optional. Quote cards should include a draft sentence in which you practice working the quote into your paper. Including your in-text citations as you write is easy when you have all the necessary information on each notecard. Don’t print this sample – it’s 36 pages!! I. Introduction A. Attention Grabber Title: it wasn't always easy for women Source: Wickham, M. (1997). Superstars of women's track & field. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House. http://dx.doi.org/0791043940 Pages: 6 Tags: 2 quote, today Direct Quote: The only thing keeping an athlete back is the limitations of her body and her ability to dream. Paraphrase: Today, many people take women in track and field for granted. Today, there is not much, if not any, discrimination or regulations against women competing on the track. Today, "the only thing keeping an athlete back is the limitations of her body and her ability to dream" (Wickham, 1997, p. 6). But this wasn't always the case for women. They had to fight for what we have today. B. Thesis Statement: American women have evolved significantly in their rights for being able to compete in track and field in the Olympics, starting with their struggles as early as ancient Greece. Once they have gained their right to compete in 1928, the years leading to today have shown an increase in women's rights and they have been able to reshape the image of track and field. -

The Black Press, African American Celebrity Culture, and Critical Citizenship in Early Twentieth Century America, 1895-1935

LOOKING AT THE STARS: THE BLACK PRESS, AFRICAN AMERICAN CELEBRITY CULTURE, AND CRITICAL CITIZENSHIP IN EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICA, 1895-1935 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION by Carrie Teresa May 2014 Examining Committee Members: Carolyn Kitch, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Susan Jacobson, Journalism & Mass Communication, Florida International University Andrew Mendelson, Media and Communication Linn Washington, External Member, Journalism ABSTRACT Through the development of entertainment culture, African American actors, athletes and musicians increasingly were publicly recognized. In the mainstream press, Black celebrities were often faced with the same snubs and prejudices as ordinary Black citizens, who suffered persecution under Jim Crow legislation that denied African Americans their basic civil rights. In the Black press, however, these celebrities received great attention, and as visible and popular members of the Black community they played a decisive yet often unwitting and tenuous role in representing African American identity collectively. Charles M. Payne and Adam Green use the term “critical citizenship” to describe the way in which African Americans during this period conceptualized their identities as American citizens. Though Payne and Green discussed critical citizenship in terms of activism, this project broadens the term to include considerations of community- building and race pride as well. Conceptualizing critical citizenship for the black community was an important part of the overall mission of the Black press. Black press entertainment journalism, which used celebrities as both “constellations” and companions in the fight for civil rights, emerged against the battle against Jim Crowism and came to embody the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance. -

Fast Girls Running Since You Last Competed in 1932

Dedication For all who support young athletes, no matter the time of day, weather, location, or score Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Historical Note Part 1: July 1928–December 1929 Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Part 2: July 1931–December 1932 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Part 3: March 1933–June 1936 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Part 4: July–August 1936 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Afterword Acknowledgments P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . .* About the Author About the Book Praise Also by Elise Hooper Copyright About the Publisher Historical Note During the 1920s and ’30s, “athletics” referred to track and field events, but given that this word has expanded over the years to include many different types of sporting events, the modern label of “track and field” is used throughout this novel. All newspaper stories, letters, telegrams, and memos in this book have been created by the author and reflect the language and attitudes used to describe women athletes during their era. Part 1 July 1928–December 1929 1.